Yingok: Difference between revisions

Philimania (talk | contribs) mNo edit summary |

Philimania (talk | contribs) |

||

| Line 405: | Line 405: | ||

==Culture== | ==Culture== | ||

Since ancient times, Yinese culture have heavily influenced !Japan and !Southeast Asia, although contemporary Yinese culture now combines influence from Calesia and eastern Abaria.<ref>{{Cite book|title=The Rough Future for Yinese Identity|author=Ronald Nook, Marston Seymour|year=2001}} Retrieved 18 July 2013.</ref> Traditional Yinese arts include crafts such as {{wp|ceramic}}s, {{wp|textile}}s, {{wp|lacquerware}}, {{wp|sword}}s and {{wp|doll}}s; performances of {{wp|Chinese opera|opera}}, {{wp|Chinese dance|dance}}, and {{wp|Chinese martial arts|martial arts}}; and other practices such as {{wp|painting}}, {{wp|poetry}}, and {{wp|calligraphy}}. Since the 1990s, Yingok has developed a system for the preservation and promotion of culture led mainly by [[Yinese Heritage]], a charity that manages over 3,000 historic monuments, buildings and places in the country.<ref>{{Cite web|url=https://www.yinwaicaan.org/fallish/index.html|website=Yinese Heritage|title=Work of Yinese Heritage}} Retrieved 11 November 2016.</ref> | |||

===Art=== | |||

'' | === Art === | ||

[[File:Yinese art.jpg|thumb|''[[Travelling to Fudou]]'' by [[Yip Zihou]], a depiction of the painter's travel from [[Sei'on]] to [[Fudou]]. It is believed to be painted from around 1712-1717.]] | |||

[[File:Daoist deity BM 1930.7-19-62.jpg|left|thumb|300x300px|A statue of a [[Semze]]<!-- 審者 -->, an example of both Yinese ceremic glazing and sculpting.]] | |||

Yinese art is characterised by a degree of continuity and relative consistency since the [[Two Kingdoms Period]]. The term "Yinese art" is often referred to ceramics, paintings, and sculptures of Yinese origin. {{Wp|Decorative arts}} is considered an important part of Yinese art, with complicated designs and intricate scenes often featured in various art forms. Ceramics, in particular, hold significant cultural and artistic value in Yinese tradition, with techniques such as porcelain production dating to the Sin Dynasty. In the modern era, Yinese art have been subject to various influences including {{Wp|realism (art)|realism}} and {{Wp|Abstract art|abstraction}} brought about by the {{Wp|industrial revolution}} and modernism. | |||

Painting is mainly done on {{Wp|silk}} or {{Wp|paper}}, utilising techniques such as {{Wp|brush painting}} and {{Wp|ink-wash painting}}. Yinese paintings typically feature themes from nature, literature, daily life, as well as mythology. The finished work could typically be displayed as scrolls such as {{Wp|hanging scrolls}} or {{Wp|handscrolls}}, although other formats such as album sheets, walls, {{Wp|lacquerware}}, and {{Wp|folding screens}}. Yinese paintings have trended towards realism over time, a trend beginning in the Hon Dynasty of the Two Kingdoms Period. Landscape painting is widely considered one of the most esteemed genres within Yinese painting, and they are generally some of the largest and most detailed works in the tradition. Landscape painting in Yinese art often depicts natural scenes, with mountains, rivers, trees, and sometimes human figures. Traditionally, Yinese paintings were done by highly skilled artists who were trained in classical techniques in an {{Wp|apprenticeship}} system and often followed strict conventions established by previous generations. | |||

Yinese ceramics is generally noted as the longest-continuous Yinese art form. The earliest types of ceramics were made during the {{Wp|Palaeolithic}} era, and ranged from construction materials such as bricks and tiles, to hand-built pottery vessels fired in bonfires or {{Wp|kiln|kilns}}. {{Wp|Blue and white pottery}} is regarded as one of the most iconic styles of Yinese ceramics, characterised by its use of blue pigment on a white background, typically achieved through the application of {{Wp|cobalt oxide}} under a clear glaze. This technique became popular during the 13th century and has since remained a hallmark of Yinese ceramic craftsmanship. Later ceramics were produced on an industrial scale without a loss in quality in workshops and factories. Because of this, very few individual ceramic makers are known. | |||

As well as porcelain, decorative arts in Yinese tradition encompass a wide array of mediums, including lacquerware, {{Wp|metalwork}}, textiles, {{Wp|furniture}}, and {{Wp|jade}}. Lacquerware holds a particularly significant place in Yinese decorative arts, with a history dating back to the [[Zhong dynasty]]. Yinese jade was attributed with magical powers, thus they were often carved into impractical objects such as weapons, {{Wp|Jade burial suit|burial suits}} and tools. In the modern day, several of these jade objects, such as the [[Sword of Honour]] (which is used to swear in the president) are used as ceremonial items or symbols of authority rather than practical tools. | |||

Yinese human sculpting derives from the practice of burying the deceased with a clay {{Wp|figurine}} likeness of themselves, a tradition dating back to the Paleolithic. These clay figurines have evolved over centuries, becoming more refined and detailed. Non-human subjects were also often depicted as {{Wp|zoomorphic}} decorations and symbolism. The materials used for sculptures have changed over time, from clay and stone during ancient times to bronze and other metals in later periods. Statues of emperors and other important figures are also common and formed a large part of historic imperial propaganda. | |||

===Architecture=== | ===Architecture=== | ||

''TBA'' | ''TBA'' | ||

===Literature=== | ===Literature=== | ||

[[File:Yinese archive.jpg|thumb|Manuscripts of [[Yinese Neo-Literature]] from the the [[Yinese Literary Archives]].]] | [[File:Yinese archive.jpg|thumb|Manuscripts of [[Yinese Neo-Literature]] from the the [[Yinese Literary Archives]].]] | ||

[[File:NDL894923 古文真宝 - 補正標註 前集 part2.pdf|thumb|An example of Yinese literature titled ''A Collection of Ancient Yinese Treasures.'']] | |||

The literary traditions of Yingok are regarded as a melting pot, as its origins can be traced back to [[History of Yingok|Ancient Yinese]], !Vietnamese, !Mongol, and [[Calesia]]n literature.<ref>[https://www.fe43.edu.yn/ 文學/燕国文学史概述 燕国文学史概述]. Retrieved 13 October 2017.</ref> One of the earliest known works is the compilation of poems called the ''[[Book of Songs]]'', which compiles about 413 sets of poems regarding daily living, the after life, and nature, dated to roughly around the late [[An dynasty]]. Other [[Yinese classics|classical texts of Yingok]] encompassed a wide range of thoughts and subjects, such as the {{wp|calendar}}, {{wp|military}}, {{wp|astrology}}, {{wp|herbology}}, and {{wp|geography}}, as well as many others. Some of these major works included the ''[[Way of Chiu]]'', and the ''[[Book of On]]'', texts that were both cornerstone of the [[Sendou]] curriculum sponsored by the state throughout the dynastic periods.<ref>{{Cite web|title=史傳文學與國古代小說|url=https://www.ynka.com/t43wre/t3987geyh5|trans-title=Historical and biographical literature and ancient Yinese novels|date=2010}} Retrieved 6 May 2014.</ref> | The literary traditions of Yingok are regarded as a melting pot, as its origins can be traced back to [[History of Yingok|Ancient Yinese]], !Vietnamese, !Mongol, and [[Calesia]]n literature.<ref>[https://www.fe43.edu.yn/ 文學/燕国文学史概述 燕国文学史概述]. Retrieved 13 October 2017.</ref> One of the earliest known works is the compilation of poems called the ''[[Book of Songs]]'', which compiles about 413 sets of poems regarding daily living, the after life, and nature, dated to roughly around the late [[An dynasty]]. Other [[Yinese classics|classical texts of Yingok]] encompassed a wide range of thoughts and subjects, such as the {{wp|calendar}}, {{wp|military}}, {{wp|astrology}}, {{wp|herbology}}, and {{wp|geography}}, as well as many others. Some of these major works included the ''[[Way of Chiu]]'', and the ''[[Book of On]]'', texts that were both cornerstone of the [[Sendou]] curriculum sponsored by the state throughout the dynastic periods.<ref>{{Cite web|title=史傳文學與國古代小說|url=https://www.ynka.com/t43wre/t3987geyh5|trans-title=Historical and biographical literature and ancient Yinese novels|date=2010}} Retrieved 6 May 2014.</ref> | ||

| Line 420: | Line 433: | ||

Yinese Neo-Literature waned during the late 16th to early 17th century and saw a brief resurgence during the early [[Saan dynasty]].<ref name=":19" /> However, it soon gave way to the rise of Archaism in [[Yinese Archaism|Yinese]] literature. Influenced by a growing interest of both the upper class and a burgeoning citizen class in the Saan dynasty in ancient learnings, including art and literature. Poets and writers such as [[Hong Hin]] and [[Syun Yanhei]] emerged during this period.<ref name=":20">{{cite book |editor-surname=Heung |editor-given=Lewis |title=A New Literary History of Yingok |year=2013 |publisher=Masten Press }} Retrieved 3 May 2019.</ref> In the late 18th-19th century, Yinese literature experienced a wave of [[Yinese Realism|realism]]. Writers such as [[Fu Waanleung]] and [[Chung Jung]] depicted the harsh realities of industrial life, colonialism, war, explored social issues, and critiqued the existing power structures.<ref name=":21">David Eriksen (2002). ''Sources of Yinese Tradition: From 1600 through the Twentieth Century''. Vol. 2. Retrieved 18 July 2013.</ref> | Yinese Neo-Literature waned during the late 16th to early 17th century and saw a brief resurgence during the early [[Saan dynasty]].<ref name=":19" /> However, it soon gave way to the rise of Archaism in [[Yinese Archaism|Yinese]] literature. Influenced by a growing interest of both the upper class and a burgeoning citizen class in the Saan dynasty in ancient learnings, including art and literature. Poets and writers such as [[Hong Hin]] and [[Syun Yanhei]] emerged during this period.<ref name=":20">{{cite book |editor-surname=Heung |editor-given=Lewis |title=A New Literary History of Yingok |year=2013 |publisher=Masten Press }} Retrieved 3 May 2019.</ref> In the late 18th-19th century, Yinese literature experienced a wave of [[Yinese Realism|realism]]. Writers such as [[Fu Waanleung]] and [[Chung Jung]] depicted the harsh realities of industrial life, colonialism, war, explored social issues, and critiqued the existing power structures.<ref name=":21">David Eriksen (2002). ''Sources of Yinese Tradition: From 1600 through the Twentieth Century''. Vol. 2. Retrieved 18 July 2013.</ref> | ||

A wave of romanticist and entertainment fiction such as {{wp|Wuxia|Mouhap}} and {{wp|Danmei|Daammei}} stories would also be seen during the waning decades of the Saan dynasty.<ref>{{Cite book|title=燕國文學傳播|trans-title=Dissemination of Yinese Literature|publisher=Samlong Press}}</ref> During the [[Fourth Winter Period]], [[Yinese Modernism]] emerged, characterised by experimentation, fragmentation, and the exploration of subjective experiences. Writers like [[Taaisuk Yun]] and [[Yu Sauloi]] pushed the boundaries of traditional writing forms and delved into abstract and introspective themes. This period also saw the rise of the [[Yinese Surrealism]] movement. In the [[Yinese Fourth Republic|post-Fourth Winter era]], Yinese literature experienced a surge of social realism and political engagement. Writers like [[Wong Sauying]], [[Lau Fongwa]] and [[Jeung Man]] used their works as a means of social critique, addressing issues such as inequality, {{wp|civil rights}}, and the impact of war. This period also saw the | A wave of romanticist and entertainment fiction such as {{wp|Wuxia|Mouhap}} and {{wp|Danmei|Daammei}} stories would also be seen during the waning decades of the Saan dynasty.<ref>{{Cite book|title=燕國文學傳播|trans-title=Dissemination of Yinese Literature|publisher=Samlong Press}}</ref> During the [[Fourth Winter Period]], [[Yinese Modernism]] emerged, characterised by experimentation, fragmentation, and the exploration of subjective experiences. Writers like [[Taaisuk Yun]] and [[Yu Sauloi]] pushed the boundaries of traditional writing forms and delved into abstract and introspective themes. This period also saw the rise of the [[Yinese Surrealism]] movement. In the [[Yinese Fourth Republic|post-Fourth Winter era]], Yinese literature experienced a surge of social realism and political engagement. Writers like [[Wong Sauying]], [[Lau Fongwa]] and [[Jeung Man]] used their works as a means of social critique, addressing issues such as inequality, {{wp|civil rights}}, and the impact of war. This period also saw the resurgence of realism again in literature. Many renowned authors such as [[Ng Laino]] and [[Jiu Sauying]] also became recognised internationally for their writing.<ref name=":20" /><ref name=":21" /> | ||

The latter half of the 20th century witnessed a diversification and expansion of literary themes and styles in Yinese literature. Yinese authors were loosely organised into literary generations. The [[Generation of Renewal]] of the 1970s and 1980s sought to challenge traditional narratives and explore new forms of expression. Writers like [[Chen Gwan]] and [[Yeung Gyun]] experimented with {{wp|stream-of-consciousness}} techniques and fragmented narratives. In the late 1980s to 2000s, the [[Generation of Identity]] emerged, focusing on themes of personal and cultural identity. Authors such as [[Lei Sauwa]] and [[Beatriz No]] emerged during this period, exploring issues of race, ethnicity, and gender. The latest generation, the [[Generation of the Globe]], which emerged in the 2000s, reflected on the growing influence of global trends and the impact of technology on Yinese literature. Their works often incorporated elements of {{wp|science fiction}} and {{wp|dystopia}}n settings.<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Three "Generations" of Yinese Literature|website=South Yinese Post|url=https://fl.southyinesepost.org/3780/565383|first=Gamhyun|last=Fong|date=2014}} Retrieved 8 March 2015.</ref><ref name=":21" /> | The latter half of the 20th century witnessed a diversification and expansion of literary themes and styles in Yinese literature. Yinese authors were loosely organised into literary generations. The [[Generation of Renewal]] of the 1970s and 1980s sought to challenge traditional narratives and explore new forms of expression. Writers like [[Chen Gwan]] and [[Yeung Gyun]] experimented with {{wp|stream-of-consciousness}} techniques and fragmented narratives. In the late 1980s to 2000s, the [[Generation of Identity]] emerged, focusing on themes of personal and cultural identity. Authors such as [[Lei Sauwa]] and [[Beatriz No]] emerged during this period, exploring issues of race, ethnicity, and gender. The latest generation, the [[Generation of the Globe]], which emerged in the 2000s, reflected on the growing influence of global trends and the impact of technology on Yinese literature. Their works often incorporated elements of {{wp|science fiction}} and {{wp|dystopia}}n settings.<ref>{{Cite web|title=The Three "Generations" of Yinese Literature|website=South Yinese Post|url=https://fl.southyinesepost.org/3780/565383|first=Gamhyun|last=Fong|date=2014}} Retrieved 8 March 2015.</ref><ref name=":21" /> | ||

| Line 455: | Line 468: | ||

*{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia Yingok|editor=Lo Wa|edition=23|publisher=World Factbook}} | *{{Cite book|title=Encyclopedia Yingok|editor=Lo Wa|edition=23|publisher=World Factbook}} | ||

===History=== | ===History=== | ||

*{{Cite book|title=The Dynastic History of Yingok|author=Leung Wei|date=1994|edition=7|publisher=Samlong Press}} | *{{Cite book|title=The Dynastic History of Yingok|author=Leung Wei|date=1994|edition=7|publisher=Samlong Press}} | ||

| Line 467: | Line 480: | ||

===Culture and politics=== | ===Culture and politics=== | ||

* | * {{Cite book|title=The Basics: Yinese Culture and Society|edition=9|author=Gary Tristan|publisher=Eagle Press}} | ||

{{Cite book|title=The Basics: Yinese Culture and Society|edition=9|author=Gary Tristan|publisher=Eagle Press}} | |||

*{{Cite book|title=Why Sendouism is So Important to Yinese People|author=Tracey Siu|edition=4|date=1993}} | *{{Cite book|title=Why Sendouism is So Important to Yinese People|author=Tracey Siu|edition=4|date=1993}} | ||

*{{Cite book|title=A Short History of Yinese Literature|publisher=Pendleton University Press|author=Sarah Green, Iver Frederiksen|date=2011|edition=14}} | *{{Cite book|title=A Short History of Yinese Literature|publisher=Pendleton University Press|author=Sarah Green, Iver Frederiksen|date=2011|edition=14}} | ||

Revision as of 12:08, 10 May 2024

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Fourth Republic of Yingok 燕華第四共和國 (Yinese) | |

|---|---|

| Anthem: 燕華國歌 Yinwàh Gwokgō "National Anthem of Yingok" | |

Location of Yingok (green) in Abaria (dark grey) | |

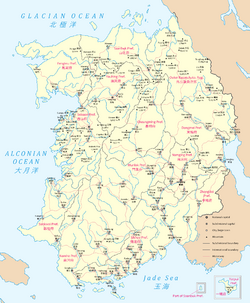

Subdivisional map of Yingok | |

| Capital | Dongsing |

| Largest city | Hoyzhau |

| Official languages | Yinese |

| Recognised regional languages | Shanese |

| Ethnic groups (2022)[1] | 83% Yinese 14% Shanese 3% Others |

| Religion (2022)[2] | 47% Sendou 41% Gregorianism 10% Irreligious 6% Others |

| Demonym(s) | Yinese |

| Government | Unitary presidential constitutional republic |

| Yeung Kapkaa | |

| Dong Dak | |

| Nam Gat | |

| Wu Suk-fan | |

| Legislature | National Diet |

| History | |

| c. 3000 BCE | |

| 12-23 June 1892 | |

| 7 March 1966-23 November 1981 | |

| 19 April 1974 | |

| 29 December 1985 | |

| Area | |

• Total | 8,037,614 km2 (3,103,340 sq mi) |

• Water (%) | 0.004 |

| Population | |

• 2022 estimate | |

• Density | 81.17/km2 (210.2/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| GDP (nominal) | 2022 estimate |

• Total | |

• Per capita | |

| Gini (2022) | medium |

| HDI (2022) | very high |

| Currency | Tungbei (銅幣/₣, TBI) |

| Time zone | UTC-9 and -7 to -5 (Yatpui Mean Time, YMT; Northwestern Yinese Time, NYT; Central Yinese Time, CYT; and Outer Razan Standard Time, ORST) |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy |

| Driving side | right |

| Calling code | X |

| Internet TLD | .yn |

Yingok (Yinese: 燕國; Jinping: Jin3 Gwok3; Yinese Hungshui Cambranisation: Yin-gwok), officially the Fourth Republic of Yingok (Yinese: 燕華第四共和國; Jinping: Jin3 Waa4 Dai6 Sei3 Gung6 Wo4 Gwok3; Yinese Hungshui Cambranisation: Yin-wàh Daih Sei Guhng-wòh-gwok) is the second largest country in Abaria. With an estimated population of over 600 million, Yingok is bordered by the Glacian Ocean to the north, Razan, X, and X to the east, the Alconian Ocean to the west, and the Jade Sea to the south. Its 13 prefectures and 1 autonomous region spans a combined area of roughly 8,037,614 km2 (3,103,340 sq mi). Yingok is a unitary presidential constitutional republic with its capital in Dongsing, the largest city in Yingok by population. The largest city in the country by area is Hoyzhau which also serves as Yingok's main economic and commercial centre. Other major urban areas include Gongbuk, Samlong, Sei'on, Donghoy, and Bikhoy.

Yingok was initially inhabited by the Zhong dynasty, followed by the An dynasty, which brought significant cultural and technological advancements. However, the An dynasty eventually fractured, leading to a fragmented political landscape and the rise of the Chiu dynasty, which brought political stability and a cultural renaissance. The region experienced invasions from the !Vietnamese and the !Mongol Empire, leading to periods of conflict and disruption. The 15th century marked the beginning of the Third Winter Period, characterised by intense competition among various factions. This era eventually gave way to the Three Kingdoms Period, with the Hon dynasty, Jeong dynasty, and emerging Dong Kingdom vying for dominance over Yingok. The Saan dynasty emerged victorious and established relative stability which lasted for nearly 3 centuries. The dynasty oversaw the rise of the Saan colonial empire. Internally, economic growth and a cultural rebirth during the period characterised the Saan dynasty's reign over Yingok. This coincided with the appearance of Calesian influence and culture at the beginning of the 17th century.

In the 19th century, Yingok embraced the Industrial Revolution, leading to rapid urbanisation and socio-political changes. The Saan dynasty's response to demands for reforms varied, leading to political unrest. The dynasty was overthrown in 1892, and Yingok went through a series of political upheavals, including various dictatorships and revolutions. Yingok remained neutral during the Great War due to internal conflicts. In 1966, a civil war erupted between different factions, culminating in a nationalist victory and the establishment of the Fourth Republic. Throughout its history, Yingok has maintained complex relationships with its neighbours, pursuing diplomacy and economic cooperation. It seeks regional stability, trade, cultural exchanges, and peaceful conflict resolution. Present-day Yingok has implemented political reforms, aiming for a more democratic and inclusive society, although challenges remain in fully implementing political freedoms and civil rights.

Yingok retains its centuries-long status as a global centre of art, science and philosophy. It is the world's leading tourist destination, receiving over 73 million foreign visitors in 2020. Yingok is a developed country with the world's X-largest economy by nominal GDP and X-largest by PPP; in terms of household net income, it ranks X in the world. Yingok performs well in international rankings of health care, life expectancy and human development. It remains a great power in regional affairs, being leading member of numerous international organisations including the United Congress, X, and the Abarian Regional Forum.

Etymology

The word "Yingok" derives from two Yinese characters: 燕 (yin) referring to the Yinese people and 國 (gwok) meaning "state". However, this name was not in use until around the rise of Yinese nationalism during the late 19th century.[7][8] The term itself (rendered as "Yin-guok") first appeared in the 1876 translation by Edwin Gallagher of End of Cycles by X which called for the abolition of the Yinese dynastic system.[9] The name was then popularised in the 1886 Pocket Guidebook and Dictionary to the Yinese State and Language, a bestseller by the Gregorian missionary Robin Wiland.[10] In popular culture, the name Yingwok is often translated as the "Kingdom of the Yin".[citation needed]

Prior to the term "Yingok", the name of the operating dynasty was always used to refer to Yingok. Outside the region however, most notable in Calesia, the name "Seushu" was primarily used to refer to Yingok. Its origins has been traced through X, X, X and X back to the !Vietnamese word chiều triều. "Seushu", rendered as "T'siuchu", first appeared in a letter dated 16 May 1497 from a X merchant who had visited X that year. The word Seushu has been suggested by many Calesian scholars to have derive from the name for the Chiu dynasty (918-132 BCE).[11] Although usage in !Vietnamese sources precedes this dynasty, this derivation is still given in various sources.[12][13]

The simplified name Yingok was in frequent use by the beginning of the 1900s. Despite the establishment of the Republic of Yingok a decade prior, many outside Yingok continued to refer to the country as Seushu until the end of the 1920s.[11] The name was also commonly written as the two-word Yin Gok until 1986 when the government officially adopted the one-word name. Some corporations and organisations founded before this date still keeps this name, including Yin Gok Electric Company, Yin Gok Hotels, Yin Gok Merchant Banking Corporation, and Yin Gok Railway Union.[14]

History

Prehistory

Yingok is home to one of the world's oldest civilisation. Early hominids have inhabited the region as early as 1.05 million years ago, with the fossils of the Yunjou Man, a Homo erectus dating back to this period.[15] The fossilised remains of early Homo sapiens of the Proto-Longic A culture dated roughly 50,000 years ago were also discovered in the Munlok region, along with stone tools and evidence of early settlements.[16][17] Paleolithic sites are also known to exist, most notably the Daisek cave paintings in Dongzhong (15,000 BCE), the Shuitou pillars near Honliun (13,000 BCE), and the Cingtongfa Rock Arts in Cingtongfa (9,000 BCE).[18]

The first evidence of pottery in Yingok dates back to around 7,000 BCE.[19] This coincided with the rise of water levels, separating Yingok with !Japan as well as providing fertile land for early agricultural practices brought about by the end of the X Ice Age. The Neolithic in Yingok witnessed the emergence of settled farming communities, marking a significant shift in human development in the region.[20] Yinese proto-writing, characterised by intricate symbols and pictograms, began to emerge during the Neolithic Age. They have existed in Tongmun near Yuthung since approximately 5,200 BCE, marking the beginning of the Proto-Longic B culture.[21][17]

Proto-Longic B marked a crucial phase in the region's development. This period witnessed the further advancement of settled farming communities and the emergence of Proto-Longic B script, a significant development in Yinese proto-writing around 4,000 BCE.[22] The society during the Proto-Longic B period was organized into small-scale chiefdoms, where local leaders held authority over their communities. These chiefdoms engaged in trade and exchange, allowing large networks of activity between the different regions of Yingok. Excavations at various sites dating back to this period have unearthed remnants of dwellings, tools, and artefacts, shedding light on their subsistence practices, craftsmanship, and social structures, most notably the Gongyun ruins near Sheunglong.[23] The transition from hunter-gatherer societies to settled agricultural communities brought about significant changes in their way of life. The first evidence of silk production also dated back to this period (3538 BCE) and was written in the historical records of the ancient settlement of Kunsaan near Qinfa.[24]

Early dynasties

According to records from the An dynasty, the Zhong dynasty was believed to have emerged during the late-4th millennium BCE, although the exact date is still debated among historians and scholars. Old legends, most notably the An Annals attribute the founding of the Zhong dynasty to the possibly mythical Emperor Yeung, a figure believed to possess exceptional wisdom and leadership qualities. The existence of the Zhong dynasty have come under scrutiny by historians and archeologists due to its minimal amount of evidence to its existence.[25] Archaeological findings along the Longcheun River dating to the period in 1944, dubbed the Longcheun culture have since been characterised as evidence of the existence of the dynasty. However, due to the lack of proper research initiatives in Yingok since the end of the Civil War, understanding of the Longcheun culture have remained minimal.[26]

The An dynasty succeeded the Zhong sometime around 2300 BCE. According to several writings from the period and later, including the An Annals and Book of On, the shift in power was related to internal struggles between two potential leaders of the state as well as external conflicts with neighbouring tribes.[27] The An dynasty marked the beginning of Yinese's dynastic system, where rulership was passed down within a particular family lineage.[28] Oracle bone script, which emerged around 2500 BCE, became the prominent form of writing during the An dynasty and is a direct ancestor of modern Yinese characters.[29] In addition, advanced irrigation techniques were used, including the earliest utilisation of dams near Tongtou. Archaeological sites dating to this period include Saangong, the Tomb of Yeung, and various other sites across southeastern Yingok.

The power of the An dynasty would later fracture and splinter, heralding the beginning of the First Winter Period in 1030 BCE.[27]

First Winter Period and Chiu dynasty

TBA

Southern invasion and Second Winter Period

TBA

Two Kingdoms Period and !Mongol rule

TBA

Third Winter and Three Kingdoms Period

TBA

Imperial dynasties and colonialism

Saan dynasty and the Imperial Reformation

TBA

Industrial Revolution

TBA

Fourth Winter Period

Yinese Revolution and First Republic

The late 19th century was characterised by the weakening of the central government, leading to a fragmentation of power across various regions of Yingok, as numerous warlords and local strongmen seized power. This marked the beginning of the Fourth Winter Period in history. By the beginning of the 1880s, the most influential faction in Yingok emerged as the Gumsha Clique in Sikhoy, led by the young Cheui Houyin who controlled much of foreign imports flowing into the country.[30][31] Prior to the onset of the Yinese Revolution, numerous coups against the Saan monarch had been attempted, bolstered by an inefficent bureaucracy, corrupt legislature, political instability, and rising anti-dynastic sentiments. Notably, the 1889 Yinese coup attempt which caused the Dongsing bombing that resulted in the death of around 173 people.[32][33]

In 1892, Ho Siyat, a prominent Yinese politician, revolutionary leader, and head of the Kungwogun milita orchestrated a successful coup in the capital in June, backed by support from several warlords and high-ranking government officials. This coup marked the beginning of a new era with the establishment of the First Republic of Yingok.[32] However, a botched attempt to arrest the royal family allowed them to escape into exile in X. This, coupled with the resistance of many warlords along the western and southern coasts as well as in the northern regions who refused to recognise the authority of the state caused many to view the new republic as an illegitimate government, despite the rampant anti-monarchist sentiments.[34][32]

The early years of the First Republic were marred by attempts by the central government to assert its control over the rest of Yingok through military force, often resulting in small-scale acts of violence and terror perpetrated by both government and warlord forces, most notably the Heungsaan Incident (1892), Lunghap Standoff (1894), and the Fongzou Bombing of 1897.[34] These incidents, among many others, further exacerbated tensions and contributed to the combined instability within the country. The most famous incident, the Battle near Muksek, led to the outbreak of the Yingok-Haksaan War on 12 February 1895 with the central government clashing with the Old Haksaan Clique. This conflict eventually led to the replacement of the Old Haksaan Clique with the pro-government New Haksaan Clique on 26 September 1897.[35]

On 16 July 1896, Ho Siyat established the Kongwotong and oversaw the ratification of the first Constitution of Yingok, which laid the groundwork for the formation of the National Diet of Yingok and the establishment of key government positions such as president, vice president, and chancellor.[36] Ho also declared himself the first president of Yingok, and announced that the first election to be held in 7 years. In reaction, several new political parties also emerged, including the Kwokmuntong in 1897 and the Kongchangtong in 1900.[37]

By 1899, anti-Kongwotong sentiments had coalesced into a alliance of warlords in the north and west of the country, challenging the authority of the First Republic and establishing the Chiusaan Confederacy, led mainly by the Fumen, Gutdong, and Choi Cliques with numerous other factions also considered members of the Confederacy.[38] This development sparked a series of confrontations between government and Confederacy forces across Yingok.[citation needed]

The assassination of Ho Siyat on the afternoon of 2 November 1900 in a shootout with local anti-government militias during a visit to Wongzen further shook the political system of Yingok. In the aftermath, vice president Baak Yingman was sworn in as acting president, declaring martial law and seized the opportunity to accuse the Chiusaan Confederacy for the death of the late president.[39] Violent clashes erupted between pro-government and pro-Confederacy groups as a result in cities like Cingdou, Gaiwing, Wodhun and Nanshui, leading to series of brutal skirmishes and small scale battles.[38] Meanwhile, President Baak ordered the crackdown on possible anti-Kongwotong militias and dissenting factions, leading to widespread arrests as well as supression of civilian protests, with many being accused of being part of "anti-government plots".[40]

In 1902, Pro-Confederacy forces launched a series of attacks against colonial authorities in X which were loyal to the Saan, thus marking the beginning of several operations which aimed to subjegate Yinese colonies under the Chiusaan Confederacy.[41]

The failure of the government to hold elections in 1903 sparked widespread discontent among the populace, particularly in urban areas where many protests and strikes were organised by the Kongchangtong (which had gained the favour of various labour movements) and other opposition groups in protest.[42] The most famous of which occured in August of 1903 where members of the United Mine Workers of Yin Gok clashed with local police in Liuham, resulting in the Liuham Massacre when the military was deployed to suppress the protesters, causing the deaths of some 40 people.[43]

Amidst the growing unrest, divisions within the military manifested, with some factions aligning with the Kongchangtong and other opposition factions within the government while others remained loyal to the government. The Kwokmuntong, meanwhile, formed close alliances with the Confederacy following negotiation in 1904 over their mutual distrust of the current government of Yingok.[44]

Empire of Yingok

On 19 May 1905, President Baak Yingman dissolved the National Diet and declared the end of the First Republic and the birth of the Empire of Yingok, citing the need for a more centralised and authoritative government to address the escalating internal conflicts. This move evoked a spectrum of reactions among the populace: while some hailed Baak's action as a necessary decision to regain order amidst the chaos that had engulfed the country, others viewed it as a betrayal of the democratic principles upon which the First Republic was founded.[45][42][40]

Around the same time, the Cheungming Clique underwent a transformation following a coup which brought the faction under the leadership of a pro-Kongchangtong Fok Yeukgong following a coup in the same year. This development provided a significant boost to the Kongchangtong, affording them a secure stronghold from which to challenge the authority of the newly formed Empire.[46][44]

The year 1906 witnessed a critical blow to colonial authorities as X capitulated to Confederacy forces on 23 June. This emboldened the Confederacy, allowing them to begin numerous other operations of this nature in X, X, and X.[41] In the same year on 7 November, the Kongchangtong and Chiusaan Confederacy solidified their opposition to the Empire by forming the United Yinese Front following the Yunzhau Agreement.[47] In winter that year, a series of brutal crackdowns by imperial forces on pro-democracy protests percieved as "traitourous groups" resulted in widespread civilian casualties and fueled resentment towards the new imperial government. Armed anti-imperial movements sprang up in various regions, particularly in rural areas where imperial control was weakest and anti-imperial groups fled.[40][48]

Meanwhile, escalating tensions and build up of troops on the borders of the Empire of Yingok and the United Yinese Front erupted into open conflict on 24 October 1908 after an incident occurred at a disputed village near Cingdou turned into a full scale battle, marking the onset of the Union-Imperial War.[49] Initially, imperial troops were successful against the forces of the Confederacy and the Kongchangtong, winning several major battles at Wasaan, Choi River, Diusaan among others. By the autumn of 1909, imperial forces had captured Heungsaan, the base of operation for the Kongchangtong and even routed a large Confederacy force near Zhongcheung.[50] However, as the war dragged on, the Empire of Yingok faced several issues, including supply shortages and logistically challenges brought about by passive resistance and sabotage by anti-imperial elements within its territories.[51]

In February of 1910, the bulk of the imperial military along the border of Sankwai were forced to withdraw due to increasingly strained supply lines and persistent guerrilla attacks by anti-imperial factions. This allowed the United Yinese Front to regroup and launch a series of counteroffensive. By the beginning of August that year, forces of the United Front had reached Tengmuk, with plans already being drawn up to campaign up the Longcheun to Dongsing.[52] In November, Kongchangtong forces recaptured Heungsaan, heralding the beginning of the end of the Empire of Yingok.[53] The recapture dealt a severe blow to imperial morale and forced the remaining imperial troops in Cheungming to retreat across the Longcheun River into Dongmei, allowing Kongchangtong forces to seize control of the majority of central Yingok.[52][50]

At the end of 1910, the Confederacy signalled the beginning of the Tengmuk-Dongsing Campaign, which aimed to capture the capital of the Empire by pushing up the Longcheun River.[52] The campaign, although brutal, with heavy casualties on both sides of the conflict, proved successful with the Battle of Dongsing occurring by mid-August of 1911. On 29 August, President Baak was captured by Confederacy forces after they stormed the Jibun Palace (which had been used as the meeting place of the National Diet). However, fighting in the city would not end until 2 September when Baak was able to issue an announcement declaring the surrender of the Empire of Yingok.[54]

Yet, the war would not end until the signing of the Treaty of Poyu on 17 September 1911 which officially dissolved the Empire of Yingok and laid the groundworks for the establishment of the Second Republic, and fighting would continue for several more months in isolated pockets of resistance until as late as 1922.[52]

Second Republic

The Yinese Provisional Government was established on 22 September 1911 with the Tongtou Declaration between the Confederacy and Kongchangtong. However, disagreements between the two factions manifested immediately over the stategy governance and revision of the constitution fuelled internal strife within the newly formed government.[55] Throughout the 1910s and 1920s, warlords would grow increasingly powerful once more, taking advantage of the central government's weakness and the squabbling among political factions, with local strongmen asserting their authority and often disregarding directives from the central government.[56]

In 1913, a new Constitution was finally agreed upon, formally establishing the Second Republic.[57] In the same year, the Chiusaan Confederacy was admmitted into the Republic increasing the territory of the Second Republic to nearly twice its size.[55] On 23 November that year, the first election took place, resulting in a Kongchangtong victory with Gong Yeunwai sworn in as president just 4 days later. However, accusations of electoral fraud marred the victory, with violence occurring in some regions of Yingok in response.[58] On 27 March 1914, the Confederacy Coalition Party would be founded by former members of the Chiusaan Confederacy, seeking to represent the interests of the late Confederacy within the newly formed government.[55][44]

By 1918, defiance of the government reached its peak when on 13 September, the State of Sikhoy was proclaimed in the Gumsha Clique by Cheui Houyin further fragmented the nation and alarming the central government,[31] setting a precedent for subsequent breakaway states in the following years which included the Fengwu State and Zenmuy Union (which would later by subjegated by Sikhoy in 1926) in 1920; the Namho Free State in 1923; the Republic of Long in 1928; Zhongdei Republic and Order of Fui in 1933; and the Teng State in 1941.[59] This resulted in numerous violent episodes as the Second Republic struggled and often failed to maintain control over potential breakaway states and warlord factions.[56][55][59]

In the 1920 election, the Kwokmuntong emerge victorious leading to the election of Lo Waijing as president.[60] This howbeit, coincided with the rise of nationalist sentiments among various ethnic minorities within the country, particularly in Outer Razan. In April 1923, the Joldu Uprising erupted in the city of the same name in the region, demanding representation and autonomy for the Hakul people. This uprising quickly escalated into a full-blown rebellion, drawing support from the Feiping Clique and further challenging the central government's authority.[61]

The rebellion was eventually crushed when the last pocket's of militia men were cleared out around the region of Mount Fofu in January of 1927.[61] In the same year, the 1927 Yinese presidential election took place, with Lo Waijing being re-elected by a small margin against the Confederacy Coalition candidate Yu Man.[62] Lo aimed to strengthen the economy, specifically from foreign trade and investment. However, his efforts were hindered by the continued dominance of warlords, by this time, numerous "toll roads" had been established by warlords throughout Yingok which heavily taxed travel and trade, impeding economic growth and stifling civilian movement around the country.[59][56]

Meanwhile, an uprising in X colony began in January 1928, fueled by dissatisfaction with colonial rule and inspired by the broader political turmoil within Yingok, in 1931 they would everthrow the colonial government and establish X.[41]

Labour strikes resurfaced in the early 1930s, in reaction to worsening economic conditions and discontent among the populace. In response, Lo Waijing announced the Six-Year Plan for Economic Reconstruction, aiming to address the economic challenges and social inequalities.[63][64] However, implementation of the plan faced significant challenges due to opposition from entrenched interests in the government many of which saw the proposed reforms as a waste time and resources which could be better utilised to combat the influence of warlords.[65]

On 23 May 1931, Saan dynasty prince in exile Chungmau returned to Yingok from exile in X, claiming legitimacy as the rightful ruler. His return sparked mixed reactions, with loyalists to the Saan dynasty concentrated mainly in Sankwai and Fengwu.[59] In the same month, the Dynastic Restoration Movement would be founded in Sankwai and a coup to overthrow the Yeungwu Clique occured successfully, giving the new movement a foothold on Yingok. A few months later in July, the New Saan dynasty was proclaimed. In January 1933, Prince Chungmau would also orchestrate the overthrow of Touhou Clique with the help of the Fengwu State which aligned with the Movement.[66]

Back in the Second Republic, tired of its inability to address ongoing crises, the Kongchangtong orchestrated the succession of the People's Union of Zhongdou and Cheungming in August 1934, removing the leaders of the Yaujeng and Wongzen Cliques in an armed coup on 2 and 3 August respectively.[67] This was followed by a month of conflict against resisting forces loyal to the deposed leaders. The Republic responded by sending their own military forces to suppress the coup while the Kongchangtong branch in the government denied any involvement, labelling their counterpart in the People's Union as "traitors of the Party". By the end of August, the Yinese Midlands War had escalated into a full-blown conflict. However, a stalemate ensued by mid-October.[68]

In November, Lo Waijing would be re-elected for a third term,[69] now an old man in his late 70s, he left most of the day-to-day governance to his vice president and cabinet members.[63] In the Yinese Midlands War, negotiations between the government and the People's Union begun in early January of 1935, bogged down by mutual distrust and conflicting demands.[68] However, an accord was able to be reached by March of 1935, leading to a ceasefire and the subsequent Treaty of Qinfa which was signed on the 11th that month, ending the war, while simultaneously, the Second Republic refused to recognise the legitimacy of the People's Union.[70]

A violent incident between Long forces and a contingency of Yinese soldiers occurred in Wochun a year later on 27 March, giving Yingok a justification to intervene militarily.[71] Thus sparking the Yingok-Long War when the Yinese Third Army crossed into Long territory on 2 April.[59] This sparked fear in other breakaway states, prompting the formation of the Jade Sea Mutual Defence Pact on 3 April 1937 with the Honliun Accords which saw the participation of all breakaway states in the south of Yingok. The Republic of Long would eventually surrender to Yingok and would be officially dissolved during the Treaty of Donggong on 20 December 1940 which also ended the war.[72]

At 14:47 CYT, on 16 June 1941, Lo Waijing died of a stroke, causing vice president Fong Yunwai to ascend to the role of acting presidency.[73] He would subsequently win the election in November.[74] However, he and various other key politicians of Yingok would be assassinated the following year in a series of bombings by pro-monarchist terrorists. Political instability would intensified due to this as competing factions within the government vied for power in the vacuum left by the deaths of the key leaders. In the aftermath, Fung Hokgong would be sworn as acting president and martial law was declared. Curfew was imposed in major cities, and the government launched a crackdown on suspected dissidents and extremist groups.[75]

1942 would see another election being held after Fung Hokgong stepped down as president due to his deteriorating health and cancer diagnosis. Hong Bokngai of the Confederacy Coalition would emerge victorious.[76] Continuing on his predecessor's crackdowns while also beginning several ineffective moderate economic and social reforms. Efforts were made to reconcile with disenfranchised communities and marginalised groups while economic restructuring initiatives were launched to diversify the economy and reduce dependence on traditional industries such as fishing and iron refining.[75][56] Hong also attempted to implement several programmes to improve social welfare, healthcare, and education. This was helped along by a fragile peace between political factions that was maintained by the government under Hong.[59]

In February of 1943, the National Diet agreed to Hong's proposal for constitutional reforms. The revision of the Constitution took place over numerous months, with the political factions clashing over the details of the amendments. Eventually, by September, the revised constitution was finalised and ratified by the National Diet on the 30th. Major changes in the new constitution included the shortening of the presidential term to six years, the establishment of term limits for the presidency to 3 terms, the assurance of the freedom of speech and thought, and the strengthening of the judiciary's independence.[77]

With the ratification of the new Constitution, Hong proclaimed the establishment of the Third Republic, thus ushering in the last era of the Fourth Winter Period.

Third Republic

- In 1944, Yingok consolidated its military power and began the Hakul Campaign.

- The Hakul Campaign aimed to assert Yingok's dominance over the northeastern cliques of Feiping and Ulu, which succeeded in 1948.

- In 1949, Hong was re-elected.

- For his second term, Hong negotiated with the Jade Sea Mutual Defence Pact to re-joining Yingok.

- The State of Sikhoy accepted the offer to be reintegrated into Yingok as a prefecture in 1951 along with the Zenmuy Protectorate which was annexed by Sikhoy.

- In 1952, the Kongchangtong was banned from the Yinese government when journalist X exposed evidence in their involvement in the succession of the People's Union.

- Protests erupted across Yingok following the banning, with supporters of the party decrying what they perceived as an infringement on their political rights.

- By 1954, the Jade Sea Mutual Defence Pact collapsed mainly due to the loss of Sikhoy and major disagreements between the Namho Free State and Zhongdei Republic.

- In the same year, the two states would go to war over a disputed farming village along their border. (Namho-Zhongdei War)

- In 1955, Kwokmuntong politician Siu Gunyu (邵冠宇) won the presidency in a closely contested election.

- The Namho Free State would win the war against Zhongdei in 1957.

- In the same year, X colony won its independence from Yingok which was unable to respond due to its mainland problems.

- In 1959, the Haksaan-Fui Reorganisation Act was passed by the National Diet, annexing all of Yingok's satellite territories, including the New Haksaan Clique, Fanyi Free City, Hoydong Clique, Wuchuen Clique, Order of Fui, and the Teng State.

- In the same year, Prince Chungmau of the Lower Saan dynasty was assassinated.

- The state itself would be paralysed with no clear line of succession.

- Two possible heirs, Princes Cheunyam and Ngawai (春蔭 and 雅惠) emerged, sparking a bitter power struggle.

- Taking advantage, both the Kongchangtong and the Yinese government sought to exploit the power vacuum.

- Yingok backed Prince Ngawai, in exchange for his pledge to integrate Sankwai and Fengwu back into the Yingok as autonomous territories.

- The Kongchangtong in the People's Union opted to invade the Lower Saan dynasty, aiming to extend their influence in preparation for what many within the party saw as an inevitable confrontation with the Third Republic.

- In the 1961 election, a split in the Confederacy vote between Hong Bokngai and Mou Mandou as well as Siu Gunyu's refusal to participate led to the victory of Yin Kyun (賢權) of the Weikuntong (威權黨; which was formed by remnants of the Kongwotong when the Empire of Yingok ended).

- Yin Kyun's administration is characterised by the strengthening of the bureaucracy and the expansion of government control over various sectors of the economy.

- By 1962, the People's Union had captured most of Fengwu, with minor skirmishes occurring against the Third Republic.

- Around the same time, the Confederacy Coalition collapsed amidst internal disagreements.

- Meanwhile, entrenchment of the two remaining major political factions within the Third Republic deepened.

- Political instability characterised the last few years of the Warlords Era.

- Corruption and inefficiency began to plague the government.

- The escalation of tensions between the Yinese government and the Kongchangtong-led People's Union, especially over the matter of the Lower Saan dynasty finally culminated in the outbreak of war in 1966.

Yinese Civil War

TBA

Fourth Republic and onwards

TBA

Geography

TBA

Climate

TBA

Biodiversity

TBA

Environment

TBA

Government and politics

Yingok is classified as a unitary presidential constitutional republic, with the president acting as head of state and head of government as well as commander-in-chief of the Yinese Armed Forces. The president and vice president are elected by direct election for six-year terms, with a limit of three terms.[78] The president appoints and presides over the cabinet, subject to the approval of the Appointments Committee. The vice president is the first in line for succession if the president resigns, is removed after impeachment, is permanently incapacitated, or dies. The vice president is usually, though not always, a member of the president's cabinet and may be appointed without the approval of the Appointments Committee. If there is a vacancy in the position of vice president, the president will appoint any member of the National Diet (usually a party member) as the new vice president. The appointment must then be validated by a three-fourths vote of the National Diet.[79] The incumbent president and vice president are Yeung Kapkaa and Dong Dak, elected in 2021.[80]

Legislative power is vested in the unicameral National Diet, with its 92 members elected for 4-year terms. Each subdivision are allowed three representatives which are elected via direct vote in their respective subdivisions, while the remaining 50 members of the National Diet are elected proportionally based on the total national vote.[81] The National Diet is headed by the Chancellor, currently Nam Gat, who is elected from among its members by a majority vote for 4-year terms. The Chancellor serves as the presiding officer of the National Diet and is responsible for facilitating legislative proceedings, and maintaining order within the National Diet.[82]

The judicial branch is headed by the Supreme Court of Yingok, which serves as the highest court in the country. It is led by the Chief Justice, currently Wu Suk-fan, and comprises of 6 associate justices. The justices are appointed by the president on the recommendation of the Judicial Committee. Each subdivision has its own court system, which handles cases within their respective jurisdictions.[83]

Since the Fung administration, corruption has been a key focus of reform in Yingok. The government has initiated various measures to combat and address corrupt practices within the country, including a lengthy anti-corruption campaign that has led to significant changes in the political and social landscape.[84] The Anti-Corruption and Ethics Commission (ACEC) was also established as well during the Fung administration as an independent agency with the primary goal of investigating and prosecuting cases of corruption at all levels of government.[85]

Allegations of corruption

TBA

Law

TBA

Subdivisions

Yingok is divided into 13 prefectures and 1 autonomous region. The prefectures are further subdivided into 394 counties and 23 municipalities. The Outer Razan autonomous region holds a higher degree of autonomy in local governance and decision-making.[86]

Each prefecture is overseen by a local assembly and is headed by a prefectural governor who is elected by the population of the respective prefecture for a term of 5 years, with a limit of three consecutive terms. the local assemblies are comprised of representatives from the counties and municipalities within each prefecture. These representatives are elected by the county or municipal population for 4 year terms. While each local assembly operates independently from the National Diet, they are ultimately accountable to the central government and must abide by national laws and policies[78]

| Flag | Name | Capital | Population |

|---|---|---|---|

|

Namging | Dongsing | X |

|

Outer Razan | Altayara | X |

|

Seisaan | Yunzhau | X |

|

Dongmei | Hoyzhau | X |

|

Sikhoy | Samlong | X |

|

Fungwu | Wunsing | X |

|

Zhongdei | Bikhoy | X |

|

Sankwai | Sei'on | X |

|

Yauhing | Cinglong | X |

|

Munlok | Wongzen | X |

|

Cheungming | Qinfa | X |

|

Namho | Gongbuk | X |

|

Yatpui | Yukgong | X |

|

Saanbak | Fumun | X |

Foreign relations

TBA

Military

The Yinese Defence Force (YDF) serves as the armed forces of Yingok, playing a pivotal role in safeguarding the nation's security, protecting its sovereignty, and contributing to regional stability. It is comprised of several branches, including the Yinese Army (YA), Yinese Navy (YN), Yinese Air Force (YAF), Yinese Space Force (YSF), and the and the Yinese National Police Force (YNPF), which also fulfils civil police duties in the rural areas of Yingok.[87] In 2022, Yingok military expenditure was $382.4 billion, or 3.9% of the Yinese GDP. Leadership of the YDF is vested in the Bureau of Defence, with the President of Yingok acting as commander-in-chief.[88] With a total personnel count of 1.37 million, the YDF is considered one of the largest military forces in the world behind X.[89]

27 military research laboratories are considered to be components of the Yinese Armed Forces, under the authority of the Bureau of Defence. These laboratories play a critical role in advancing the YDF's technological capabilities, supporting research and development efforts to enhance the military's readiness and effectiveness.[90] In terms of intelligence, the military branch is led by the Military Intelligence Division of Yingok (MIDY) and serves under the Bureau of Defence, while the civilian branch is led by the National Intelligence Office (NIO) under the Yinese National Police Force.[citation needed] Yingok's cybersecurity capabilities are regularly ranked as some of the most robust of any nation in the world.[91]

In 2021, national conscription was abolished by the National Diet.[92]

Economy

TBA

Industries

TBA

Energy

TBA

Science and technology

TBA

Infrastructure

There are approximately 130,000 km (90,000 mi) worth of highways in Yingok making the country one of the most well connected nations in the world after X. It is jointly maintained and upkeeped by the Yinese Bureau of Infrastructure and the Yinese Highway Administration.[93] Sikhoy prefecture is home to the densest network of roads and highways in Yingok, with Namging right behind them. Yinese roads also handle substantial international traffic from X.[94] The car market are dominated mainly by domestic brands, however Calesian cars are not unheard of. Brands in Yingok include GSheung, Baakmin, and Nordhagen. Yingok is also one of the world's largest exporter of cars as of 2023.[95]

In terms of railway, it stretches roughly 60,000 km (37,000 mi) as of 2022. Locally, it is seen as an outdated and unreliable form of transportation as it is prone to delay and accidents. The Yinese railway is operated by the Railway Company of Yingok (RCY), a state owned corporation. Railways in Yingok are particularly strained during the holidays, especially during the new year celebration, when roughly 350 millions people would travel to the countryside to visit their families and vice versa via rail annually. Trains in Yingok could travel at the maximum speed of 320 km/h (199 mph). The RCY also possesses routes to X. Urban trains such as the Dongsing Subway are slightly more developed, with most major cities in the south and east having underground or tramway services complementing bus services.[96]

There are 240 airports in Yingok.[97] Hoyzhau International Airport is by far the largest and busiest airport in the country, handling the vast majority of popular and commercial traffic in the eastern half of the country. Yinese Airlines is the national airline, although numerous private airline companies provide domestic and international travel services.[98] There are ten other major airports in Yingok, the largest of which is the Hong Bokngai International Airport in Dongsing. Yingok is also home to several leading aerospace companies including Washun, Fongzou Aviation, and Aero Engine Group of Bakmun.[99]

Yingok has over 2,000 river and seaports, about 210 of which are open to foreign shipping. Some of the most busiest port in Yingok include the Ports of Donghoy, Honglau, Cuiwan, Gumsha, and Bikhoy, with Donghoy being the most busiest port in Yingok.[100] The country's inland waterways are one of the world's longest, at a total 8,747 km (5,435 mi).[101]

Tourism

TBA

Demographics

TBA

Religion

TBA

Urbanisation

Since the industrial revolution, Yingok has been a highly urbanised country. The percentage of the country's population living in urban areas increasing from 35% in 1900 to over 60% in 2023.[102] Yingok also has X cities with a population of over 1 million, with 14 megacities as of 2020. The largest cities by population (Excluding metropolitan area population) being Hoyzhau (23,732,130), Dongsing (19,218,537), Samlong (12,754,552), Donghoy (12,694,268), Bikhoy (11,540,623), Sei'on (11,321,644), Gongbuk (10,756,313), Madan (10,242,844), Yunzhau (9,940,150), and Gumsha (9,831,581).[103] Rural flight continues to be a political issue throughout Yingok.

| Rank | Prefecture | Pop. | Rank | Prefecture | Pop. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Hoyzhau  Dongsing |

1 | Hoyzhau | Dongmei | 23,732,130 | 11 | Poyu | Namging | 9,207,952 |  Samlong  Donghoy |

| 2 | Dongsing | Namging | 19,218,537 | 12 | Pingyi | Sikhoy | 8,786,361 | ||

| 3 | Samlong | Sikhoy | 12,754,552 | 13 | Punlong | Sikhoy | 8,477,465 | ||

| 4 | Donghoy | Dongmei | 12,694,268 | 14 | Fatlo | Zhongdei | 7,375,682 | ||

| 5 | Bikhoy | Zhongdei | 11,540,623 | 15 | Liuham | Dongmei | 7,470,735 | ||

| 6 | Sei'on | Sankwai | 11,321,644 | 16 | Yuthung | Namging | 6,959,784 | ||

| 7 | Gongbuk | Namho | 10,756,313 | 17 | Honglau | Sikhoy | 6,256,090 | ||

| 8 | Madan | Sikhoy | 10,242,844 | 18 | Mukleung | Namho | 6,152,003 | ||

| 9 | Yunzhau | Seisaan | 9,940,150 | 19 | Cuiwan | Sikhoy | 5,749,952 | ||

| 10 | Gumsha | Sikhoy | 9,831,581 | 20 | Qinfa | Cheungming | 5,549,253 | ||

Language

TBA

Education

TBA

Health

Culture

Since ancient times, Yinese culture have heavily influenced !Japan and !Southeast Asia, although contemporary Yinese culture now combines influence from Calesia and eastern Abaria.[104] Traditional Yinese arts include crafts such as ceramics, textiles, lacquerware, swords and dolls; performances of opera, dance, and martial arts; and other practices such as painting, poetry, and calligraphy. Since the 1990s, Yingok has developed a system for the preservation and promotion of culture led mainly by Yinese Heritage, a charity that manages over 3,000 historic monuments, buildings and places in the country.[105]

Art

Yinese art is characterised by a degree of continuity and relative consistency since the Two Kingdoms Period. The term "Yinese art" is often referred to ceramics, paintings, and sculptures of Yinese origin. Decorative arts is considered an important part of Yinese art, with complicated designs and intricate scenes often featured in various art forms. Ceramics, in particular, hold significant cultural and artistic value in Yinese tradition, with techniques such as porcelain production dating to the Sin Dynasty. In the modern era, Yinese art have been subject to various influences including realism and abstraction brought about by the industrial revolution and modernism.

Painting is mainly done on silk or paper, utilising techniques such as brush painting and ink-wash painting. Yinese paintings typically feature themes from nature, literature, daily life, as well as mythology. The finished work could typically be displayed as scrolls such as hanging scrolls or handscrolls, although other formats such as album sheets, walls, lacquerware, and folding screens. Yinese paintings have trended towards realism over time, a trend beginning in the Hon Dynasty of the Two Kingdoms Period. Landscape painting is widely considered one of the most esteemed genres within Yinese painting, and they are generally some of the largest and most detailed works in the tradition. Landscape painting in Yinese art often depicts natural scenes, with mountains, rivers, trees, and sometimes human figures. Traditionally, Yinese paintings were done by highly skilled artists who were trained in classical techniques in an apprenticeship system and often followed strict conventions established by previous generations.

Yinese ceramics is generally noted as the longest-continuous Yinese art form. The earliest types of ceramics were made during the Palaeolithic era, and ranged from construction materials such as bricks and tiles, to hand-built pottery vessels fired in bonfires or kilns. Blue and white pottery is regarded as one of the most iconic styles of Yinese ceramics, characterised by its use of blue pigment on a white background, typically achieved through the application of cobalt oxide under a clear glaze. This technique became popular during the 13th century and has since remained a hallmark of Yinese ceramic craftsmanship. Later ceramics were produced on an industrial scale without a loss in quality in workshops and factories. Because of this, very few individual ceramic makers are known.

As well as porcelain, decorative arts in Yinese tradition encompass a wide array of mediums, including lacquerware, metalwork, textiles, furniture, and jade. Lacquerware holds a particularly significant place in Yinese decorative arts, with a history dating back to the Zhong dynasty. Yinese jade was attributed with magical powers, thus they were often carved into impractical objects such as weapons, burial suits and tools. In the modern day, several of these jade objects, such as the Sword of Honour (which is used to swear in the president) are used as ceremonial items or symbols of authority rather than practical tools.

Yinese human sculpting derives from the practice of burying the deceased with a clay figurine likeness of themselves, a tradition dating back to the Paleolithic. These clay figurines have evolved over centuries, becoming more refined and detailed. Non-human subjects were also often depicted as zoomorphic decorations and symbolism. The materials used for sculptures have changed over time, from clay and stone during ancient times to bronze and other metals in later periods. Statues of emperors and other important figures are also common and formed a large part of historic imperial propaganda.

Architecture

TBA

Literature

The literary traditions of Yingok are regarded as a melting pot, as its origins can be traced back to Ancient Yinese, !Vietnamese, !Mongol, and Calesian literature.[106] One of the earliest known works is the compilation of poems called the Book of Songs, which compiles about 413 sets of poems regarding daily living, the after life, and nature, dated to roughly around the late An dynasty. Other classical texts of Yingok encompassed a wide range of thoughts and subjects, such as the calendar, military, astrology, herbology, and geography, as well as many others. Some of these major works included the Way of Chiu, and the Book of On, texts that were both cornerstone of the Sendou curriculum sponsored by the state throughout the dynastic periods.[107]

Literature in Yingok saw its first golden age during the Chiu dynasty. Poets such as Ho Ting and Wong Linggwan paved the way for the emergence of realism and romanticism respectively in Yinese literature. Several well known Yinese tales also date back to this era, including the Spirit of Winter, and the Lands to the East, folkloreic and mythological tales that would define Yinese literature for much of Yinese history. A great library would also be built during the 4th century BCE, which would be preserved by the subsequent invading !Vietnamese people and later burned by the !Mongol Empire in 1373.[108]

A second golden age for Yinese literature occurred during the late Hon dynasty. Promoted by the Yinese Monarchy, prominent literary figures emerged during this period. Writers and poets such as Laai Chi and Daai Tang become prominant names in Yinese high society as a result of their writing. The Yinese Neo-Literature movement emerged during this era. Initially as a rebellion against !Mongol cultural dominance. Emerging during the early 15th century, the literary movement embraced ideas such as social commentary.[108][109]

Yinese Neo-Literature waned during the late 16th to early 17th century and saw a brief resurgence during the early Saan dynasty.[109] However, it soon gave way to the rise of Archaism in Yinese literature. Influenced by a growing interest of both the upper class and a burgeoning citizen class in the Saan dynasty in ancient learnings, including art and literature. Poets and writers such as Hong Hin and Syun Yanhei emerged during this period.[110] In the late 18th-19th century, Yinese literature experienced a wave of realism. Writers such as Fu Waanleung and Chung Jung depicted the harsh realities of industrial life, colonialism, war, explored social issues, and critiqued the existing power structures.[111]

A wave of romanticist and entertainment fiction such as Mouhap and Daammei stories would also be seen during the waning decades of the Saan dynasty.[112] During the Fourth Winter Period, Yinese Modernism emerged, characterised by experimentation, fragmentation, and the exploration of subjective experiences. Writers like Taaisuk Yun and Yu Sauloi pushed the boundaries of traditional writing forms and delved into abstract and introspective themes. This period also saw the rise of the Yinese Surrealism movement. In the post-Fourth Winter era, Yinese literature experienced a surge of social realism and political engagement. Writers like Wong Sauying, Lau Fongwa and Jeung Man used their works as a means of social critique, addressing issues such as inequality, civil rights, and the impact of war. This period also saw the resurgence of realism again in literature. Many renowned authors such as Ng Laino and Jiu Sauying also became recognised internationally for their writing.[110][111]

The latter half of the 20th century witnessed a diversification and expansion of literary themes and styles in Yinese literature. Yinese authors were loosely organised into literary generations. The Generation of Renewal of the 1970s and 1980s sought to challenge traditional narratives and explore new forms of expression. Writers like Chen Gwan and Yeung Gyun experimented with stream-of-consciousness techniques and fragmented narratives. In the late 1980s to 2000s, the Generation of Identity emerged, focusing on themes of personal and cultural identity. Authors such as Lei Sauwa and Beatriz No emerged during this period, exploring issues of race, ethnicity, and gender. The latest generation, the Generation of the Globe, which emerged in the 2000s, reflected on the growing influence of global trends and the impact of technology on Yinese literature. Their works often incorporated elements of science fiction and dystopian settings.[113][111]

In recent years, Yinese literature has continued to evolve and diversify. The rise of independent publishing and online platforms has provided opportunities for emerging voices and marginalised perspectives to be heard. Literary festivals and events, such as the Samlong Literary Expo and the Hoyzhau Book Fair, attract both local and international authors. Yinese literature has also gained recognition on the global stage, with several authors receiving prestigious literary awards such as the X as well as translations of Yinese works.[114]

Philosophy

TBA

Cuisine

TBA

Media

TBA

Music

TBA

Cinema

TBA

Fashion

TBA

Sports

TBA

National symbols and holidays

TBA

References

- ↑ "Ethnic Makeup Report 2021-2022". stats.gov.yn. 2022. Retrieved 12 March 2023.

- ↑ Yun, Salgado (2023). "Religions of Abaria in the Modern Day". Religion and Society Abaria. Retrieved 8 December 2023.

- ↑ "2021-2022 Yinese Population Report" (PDF). Government of Yingok. Retrieved 25 January 2023.

- ↑ 4.0 4.1 4.2 4.3 "2021-2022 Economic Analysis" (PDF). Government of Yingok. Retrieved 28 February 2023.

- ↑ "Gini index – Yingok". Gini index. 2022. Retrieved 4 January 2023.

- ↑ "HDI Report 2021-2022" (PDF). United Congress Development Programme. 16 January 2023. Retrieved 23 January 2023.

- ↑ Dong, Siulap (2005). 「燕國」的由來 [Origins of "Yingok"]. Samlong: Samlong Press. pp. 25–27. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- ↑ Hau, Kokhei (2010). "The Evolution of Yinese Nationalism: From Concept to Reality". Abarian Studies. 42 (3): 315–330. Retrieved 8 March 2011.

- ↑ Gallagher, Edwin (1876). End of Cycles. Sydenham: Great Translation House. Retrieved 22 January 2008.

- ↑ Wiland, Robin (1886). Pocket Guidebook and Dictionary to the Yinese State and Language. Retrieved 20 December 2014.

- ↑ 11.0 11.1 Ramsey, Lee (23 September 2017). "A Historical Analysis of "Seushu" in Calesian Context". Historical Perspectives. Retrieved 28 April 2020.

- ↑ "Encyclopedia Calesia - Yingok". Encyclopedia Calesia. 5. 2019. pp. 320–321. Retrieved 14 February 2023.

- ↑ What is the etymology of Yingok?. Retrieved 5 May 2020.

- ↑ Ponce, Johnny (21 October 2007). "Yin Gok or Yingok". The Analyser. Retrieved 16 March 2018.

- ↑ "Yunjou Man: Homo erectus Fossils" (PDF). The Paleoarchaeological Journal. 24 May 1990. Retrieved 24 August 2019.

- ↑ Ming, Timyu (1978). "Discovery of Homo captiosus Fossils in Munlok". Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology. 42 (3): 125–138. Retrieved 12 November 2016.

- ↑ 17.0 17.1 "The Three Periods of Pre-Dynastic Yingok". Yingok Cultural Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 17 June 2017.

- ↑ "Paleolithic Art in Yingok". Yingok Archaeological Society. Retrieved 8 March 2012.

- ↑ "The Rise of Pottery in Yingok". Journal of Ancient Civilizations. Retrieved 19 July 2021.

- ↑ Johnson, Alice (1993). "The Neolithic Age in Yingok". Archaeology Today. 18 (2): 85–104. Retrieved 26 April 2010.

- ↑ "Proto-Writing in Tongmun". Yingok Cultural Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 2 October 2015.

- ↑ Thomas, John (1994). "Emergence of Proto-Hangic B Script: A Breakthrough in Yinese Proto-Writing". Journal of Ancient History. 15 (2): 43–57. Retrieved 12 September 2017.

- ↑ Lee, On (1984). "Unearthing the Past: Excavations and Discoveries at Gongyun Ruins". Journal of Yinese Archaeology. 25 (3): 82–99. Retrieved 2 December 2009.

- ↑ "Silk Production in Proto-Hangic B". Yinese Historical Society. Retrieved 23 May 2013.

- ↑ "The Zhong dynasty: Fact vs Fiction". zhongchiu.com. Retrieved 13 June 2016.

- ↑ "Why We Know So Little About Our First dynasty". Yingok Cultural Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 14 November 2014.

- ↑ 27.0 27.1 "Writings from the An dynasty". Journal of Ancient History. 17 (3): 45–67. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ↑ "Politics of the An dynasty". Yingok Historical Society. Retrieved 14 November 2011.

- ↑ "Oracle Bone Script: A Study of Ancient Writing Systems". Journal of Archaeology and Anthropology. 12 (2): 78–95. Retrieved 25 January 2013.

- ↑ "Fourth Winter Period in Yingok". HistoricalChronicles.com. Retrieved 21 February 2017.

- ↑ 31.0 31.1 Jeung, Yutung (15 May 1983). "金沙集團在锡海的崛起" [Rise of the Gumsha Clique in Sikhoy]. 燕國歷史. 15 (2): 45–68. Retrieved 30 September 2012.

- ↑ 32.0 32.1 32.2 "The Yinese Revolution". Yingok Historical Society. Retrieved 20 June 2015.

- ↑ Leung, Hungwai (20 November 1899). "Remembering the Dongsing Bombing: Tragedy in Yingok". Dongsing Gazette. Retrieved 11 December 2008.

- ↑ 34.0 34.1 Wong, Meng (1978). 何士日:第一共和國建築師 [Ho Siyat: Architect of the First Republic]. Yutzhau University Publishing. Retrieved 24 March 2010.

- ↑ Zheung, Lily (5 March 1998). "Origins of the Yingok-Haksaan War" (PDF). Journal of Military History. 7 (3): 112–129. Retrieved 24 June 2017.

- ↑ "燕國憲法:全文" [Constitution of Yingok: Full Text] (PDF). Sikhoy Post. 16 July 1896. Retrieved 29 August 2014.

- ↑ Sing, Zi-keung (1997). "The Birth of Political Parties in Yingok". Political Review of Yingok. 1 (1): 45–60. Retrieved 28 November 2011.

- ↑ 38.0 38.1 "The Rise of the Chiusaan Confederacy". Yingok Cultural Heritage Foundation. 21 April 1999. Retrieved 29 January 2010.

- ↑ "總統遇刺;副總統宣布戒嚴" [President Assassinated; Vice Declares Martial Law]. Dongsing Gazette. 3 November 1900. Archived 21 October 1999. Retrieved 12 May 2016.

- ↑ 40.0 40.1 40.2 Ng, Kate (1991). "The Crimes of Baak Yingman". Political Review of Yingok. 4 (2): 120–135. Retrieved 25 June 2018.

- ↑ 41.0 41.1 41.2 Ouest, Emile (2006). Fate of the Abarian Power. Retrieved 18 February 2009.

- ↑ 42.0 42.1 "Decline of the First Republic". Yingok Historical Society. Retrieved 12 November 2017.

- ↑ "The Liuham Massacre: A Dark Day in Yingok History". South Yinese Post. 7 August 2003. Retrieved 29 August 2020.

- ↑ 44.0 44.1 44.2 "The Kwokmuntong-Confederacy Alliance". Kwokmuntong Historical Archives. 1994. Retrieved 20 July 2014.

- ↑ "The End of the First Republic: Baak Yingman's Declaration". Yingok History Blog. 19 May 2001. Retrieved 23 November 2021.

- ↑ Tong, Philip (June 1995). "Cliques of the Fourth Winter Period: Cheungming and Successors". Political Review of Yingok. 23 (2): 45–67. Retrieved 19 May 2017.

- ↑ Avni, Humphrey (18 November 1996). "The Formation of the United Yinese Front". The Revolutionaries. 1 (1): 1–20. Retrieved 23 December 2009.

- ↑ Choi, Tinmei (2006). "The Winter Crackdowns of 1906: A Dark Chapter in Yinese History". Yingok Cultural Heritage Foundation. Retrieved 4 August 2012.

- ↑ Lai, Saanping (27 October 1908). "清都事件,燕軍出動" [Incident at Cingdou, Yinese Soldiers Mobilised]. Samlong Bellman. Archived 7 June 2002. Retrieved 27 February 2013.

- ↑ 50.0 50.1 Wong, Oigwok (2003). "The Strategy of the Empire of Yingok" (PDF). Journal of Military History. 12 (3): 89–112. Retrieved 8 June 2017.

- ↑ Porter, Theresa; Smith, Rick (24 October 2008). "The Union-Imperial War: 100 Years Later". Daily Times. Retrieved 18 July 2015.

- ↑ 52.0 52.1 52.2 52.3 Zheung, Seigit (August 1910). "The United Yinese Front's Counteroffensive during the Union-Imperial War: The Battle for Tengmuk". Journal of Military History. 15 (1): 45–78. Retrieved 13 March 2018.

- ↑ Anonymous (12 November 1910). "共產黨軍克香山" [Kongchangtong Troops capture Heungshan]. Chiusaan Ear. Archived 14 November 2001. Retrieved 1 January 2012.

- ↑ Gu Tin (31 August 1911). "總統捕;戰束?" [President Captured; War Over?]. Dongsing Gazette. Archived 23 May 2002. Retrieved 11 August 2014.

- ↑ 55.0 55.1 55.2 55.3 E. Jenkins (10 October 2000). How Two Governments Ran a Country (5 ed.). Eagle Press. p. 53-55. Retrieved 22 April 2015.