User:Char/sandbox5

United Republics of Aztapamatlan Cepan Tlacatlatocayotl Aztapamatlan Iámendu Uniachá Astapamatan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital | Quitzapatzaro |

| Largest city | Angatahuaca |

| Official languages | Nahuatl Purépecha |

| Ethnic groups | |

| Demonym(s) | Aztapaman, Aztapamitec |

| Legislature | Necentlatiloyan |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,845,600 km2 (712,600 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2022 census | 70,103,619 |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Per capita | $30,031 |

| HDI (2019) | very high |

| Currency | Amatl |

| Driving side | right |

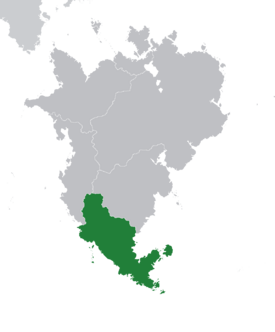

The United Republics of Aztapamatlan (Nahuatl: Cepan Tlacatlatocayotl Aztapamatlan, CTA; Purépecha: Iámendu Uniachá Astapamatan, IUA), also known as the United Republics or as Aztapamatlan, is a country located in southern Oxidentale bordered to the north by Kayahallpa and Yadokawona, to the east by the Ooreqapi ocean, to the south by the Amictlan ocean, and to the west by the Makrian ocean. It is a federation of twenty-two constituent republics governing a population of 70 million inhabiting a territory of 1.8 million square kilometers across the southern reaches of the continent and several outlying islands and archipelagos. The national and constituent governments of Aztapamatlan are categorized as democratic kritarchies, also called Judicates, in which the government is formally controlled by the courts and the leading judges of the country while sustaining democratic means of political participation and redressement of grievances. Aztapamatlan operates under a unique economic system called Calpollism, a system that has been called a hybrid of capitalism and communalism.

Aztapamatlan first emerged as a rising imperial power in the south of Oxidentale in the 8th century and made its mark on the region as a fanatically religious and militantly expansionist power. The territory that would become Aztapamatlan had been settled by more than ten thousand years prior, and occupied by many kingdoms and petty empires through the millenia. However, Aztapamatlan became the first ever state to unify the entire region by the end of the 10th century. Following the taming of the rugged interior of the country, the Aztapamatlan state began to sponsor maritime endeavors and oceanic exploration which would culminate in the discovery of a eastward route across the ocean to the continent of Malaio. Begining in the 15th century, Aztapamatlan governed regions of Malaio through a system of mixed vassals and areas of direct rule. The country retains some influence in this region by way of its cultural, religious and economic ties to Malaio, many of which are more recent relationships established long after the mid 18th century decline of the Aztapamatlan transoceanic empire. Periods of turmoil, cloistered isolationism and violent political revolution followed the decline of the empire and would centuries later culminate in the establishment of the United Republics government over the country in 1904 and the ascent to power of the Judicates in 1924 which would see the establishment of the modern state.

The chief ethnic groups of the country are the Nahuas who are the majority ethnicity found all across the region, and the Purépechas who have been historically dominant in the Aztapamatlan empire. However, Aztapamatlan is extremely ethnically diverse with ten more formally recognized native ethnities and countless more unrecognized trbes and nations inhabiting the country alongside many groups who have migrated to the country from overseas. Although nahuatl was the lingua franca and is now the primary official language of the CTA, assimilation by the ethnocultural plurality never took place despite more than a century of near continuous rule by a Purépecha-Nahua state. This is in part due to the mountainous and difficult terrain of the Aztapaman hinterland which allowed the many nations inhabiting the interior to remain partially autonomous in spite of the imperial conquest many centuries ago. The religious situation in the country is similarly diverse, with many competing religious doctrines alongside foreign faiths primarily introduced by immigrants to the country.

The Calpollist economy of Aztapamatlan is considered to be heavily industrialized with a major investment in the secondary and tertiary sectors, generally industrial manufacturing and a nascent service economy. Production of heavy machinery, machine components, and some high tech products such as semiconductor chips used in high tech manufacturing make up the bulk of the modern Aztapaman economy, although many finished products and some consumer products are also produced in the country. Financial and business services have gradually emerged in the modern Calpollist economy, forming the vanguard of a growing service sectory that spans entertainment, tourism and communications and software. Significant disparity exists between the Republics in the realm of economic development however, some regions of the country's interior may still function under an agrarian economy largely unchanged for centuries while the wealthy and populous coastal cities have become internationally significant centers of science, technology and commerce.

Etymology

Long standing names for the region in the far south of Oxidentale were Tsakapuka (or Tzaqapuqa), meaning the "Land of Stones", and the Nahuatl Huitztlan, simple meaning the south. The territory was never called Aztapamatlan at any point prior to the rise of the empire by the same name, and indeed Aztapamatlan to refer to the region itself rather than the state did not emerge as a common expression until the mid 11th century, many hundreds of years after the emergence of the empire. Aztapamatlan breaks down into Aztapamitl or "heron feather banner", itself a compound noun made up of Aztatl or "heron" and Pamitl or "banner", and the locative suffix -matlan meaning "underneath" or "in the grasp". Put together, the composite noun Aztapamatlan can be translated as "Under the heron-feather banner". Herons and their feathers are closely associated with the god Curicaueri-Xiuhtecuhtli, patron deity to the Purépecha which subsequently became the henotheistic god-head of the Aztapaman imperial cult. A standard made of white heron feathers was the symbol of religious fervor and military might in the Aztapamatlan state, closely tied with this dominant political order and thereby lending its name to the new multiethnic empire.

Economy

Agriculture

Maize and potato agriculture is the basis of Aztapaman agriculture, with the country being internally divided between highland areas in the interior which depand on potato as their staple and the coastal plains and foothills regions which are based on maize agriculture. Crops found alongside these staples include beans, tomatoes, chilies, cassava and squash. All of these crops are indigenous to Oxidentale and were either domesticated in or introduced to Aztapamatlan over the course of thousands of years of history and migration, and remain the principle staples of the Aztapaman diet and the myriad local cuisines found across the country. Much of the agricultural activities aimed at food production are based on the system of the traditional communal farm, which over time evolved into ownership and labor model today known as Calpollism. Under this system, the land is held in common and usufruct rights are granted to members of the local community to cultivate sectors of this common land. This traditional calpulli is found primarily in the rural regions of the country, while the industrial Calpollist model is employed to modern mass agriculture in the country's more intensively cultivated arable land. In these latter zones, maize is also harvested but so are sunflowers, soybeans, flax and sorghum which are used to produce edible oils and for the production of biofuels on an industrial scale. Livestock such as chickens, pigs, cattle and sheep are also raised in the hills of northern and central Aztapamatlan using the industrially produced oilseed plants as well as available pasture for animal feed. A minor component of the agricultural sector is the production of wood and paper products through logging, which was originally based on the dense forests of the Aztapaman interior but has since largely transitioned to tree plantations operated on land already cleared of natural woodlands. Intensive cultivation of monocultures of specially selected species, generally of conniferous tree varieties, allows these plantations to produce a large quantity of timber for wood and paper products in a short amount of time and is considered more sustainable as well as more economically sound than the continued harvesting of the now limited regions of natural old growth forests.

Fishing, which is considered a part of the agricultural sectors, is a major industry in Aztapamatlan and contributes to nearly one third of all food production within the CTA. Much of this fishing takes place in the Teeming Sea fishery off the eastern coast of the country, although Aztapaman fishing vessels have ventured further and further afield across the Makrian and Ooreqapi oceans in response to declining fish stocks of the Teeming Sea and the corresponding government restrictions. Sardines and anchovies are fished, while shortfin squid and hake are approaching status as overfished. The Teeming Sea Saurel is overfished. Southern bluefin and Yellowfin tuna are highly sought after by those fishing vessels that venture into the open oceans beyond the coastal fisheries of Aztapamatlan. The average Aztapaman consumes around 25 kilograms of fish every year, making it one of the largest per capita consumers in the world. Increasingly, even the well developed Aztapaman fishing industry is not able to meet mounting demand and fish as well as other seafood such as crustaceans must be imported from other countries or fishing contracted out to foreign fishing firms. The fishing industry makes up three quarters of the economic contribution of the agricultural sector and is far more luctrative relative to the size of its labor force than the cultivation and tending activities taking place on the mainland.

Manufacturing

Production of manufactured goods makes up the bulk of the Aztapaman economy by GDP and percentage of the national workforce employed in these secondary sector. Development of industrial manufacturing in Aztapamatlan began in the early 20th century with the expansion of steel production and subsequent diversification of machine producing factories and mechanical works through the 1910s and 1920s. The mainstay of the manufacturing sector remains the production of mechanical components, metal products and machines used in other industrial sectors and factories. Much of the industrial equipment used in Aztapamatlan is itself manufactured in the CTA, while such products are also widely exported to the industrial economies of the wider world. Simple assembly has for the most part been replaced across country by more complex manufacturing, particularly of engines, vehicles, aircraft and ships. In particular, Aztapamatlan is one of the world leaders in the manufacturing of oceangoing vessels, which is done in large assembly facilities producing prefabricated sections to be transported to a building dock to be assembled into a completed ship. The CTA produces container, bulk carrier, tanker and ro-ro ships for commerical use by domestic and foreign firms. Shipbuilding activities are widespread in the country's many major port cities and directly or indirectly employs two in every seven Aztapamans. State owned manufacturers are also involved in the production of warships for the Aztapaman navy as well as international military clients. Besides the manufacture of components for the international market, often components for more complex vehicles and machines, a number of motor vehicles and aircraft are aditionally manufactured in the CTA. Auto industry factories are well established in the interior urban centers of the country since the mid 1950s, while the growth of aeronautics industry was initially spurred by the Aztapaman space program and would only develop into a conventional Calpollist industrial sector in the late 1980s.

The Aztapaman manufacturing sector is itself focused primarily on products intended for industry. With the exception of shipbuilding, finished vehicles, aircraft and other such completed products make up a small portion of the sector. Instead, most of the products produced in Aztapamatlan are intermediate components or machinery to be exported and used by foreign industrial firms. Another large section of the manufacturing industries in the CTA is metallurgical, producing the necessary steel and other metal alloys to be used in the manufacturing process, while specific strategic rescources such as lithium, coltan and nickel are imported from other countries to facilitate industrial processes. A small but lucrative subsector of manufactruing in the CTA is high tech manufacturing, in particular the Semiconductor industry consolidated under the Centlaxotlaltica corporation chip foundries. While the costs of entry into high tech manufacturing are too high for many industrial calpolli to be able to afford, the high profitability of the semiconductor and other high technology industries is expected to draw larger calpolli conglomerates into these sectors in the near future.

Energy

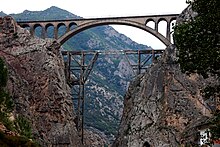

Aztapaman electric power is a valuable local export in southern Oxidentale, where it is sold across the northern border to Kayahallpa and in particular Yadokawona. Electricity generation in the CTA is centralized under Cenikpitikayotl corporation, an anonymous limited company under majority ownership by the government of Aztapamatlan. Cenikpitikayotl does not have a total monopoly in the energy sector in Aztapamatlan, but remains the largest energy corporation by far in part thanks to government subsidies for its operations. Electricty arrived in Aztapamatlan relatively late, first appearing in the 1890s and still not reaching many rural regions of the mountainous interior until the mid 1940s. When it finally began to expand, the electrification of the country was accomplished thanks to coal and gas-fired power stations. Coal stations would fall in popularity as the coal supply was prioritized for industrial uses, while natural gas popularity would decline severely following the 1969 Angatahuaca Blackout and the global oil crisis of the early 1970s which drove electricty prices in Aztapamatlan to astronomical levels. After these crises, companies like Cenikpitikayotl received major financial incentive to establish alternative power infrastructure for which nuclear was favored as a stable, year round source of energy which could increase or reduce production based on market conditions rather than being reliant on environmental conditions like other renewables. The first nuclear reactor, the now famous Angatahuaca-Chapulco Power Station, began operation in 1981 and would soon be joined by dozens more supplying the enormous energy demands of the large coastal urban centers of the CTA. Today, there are a total of 61 nuclear power plants in Aztapamatlan. Hydroelectricty takes up the position of distant second in terms of power generation in Aztapamatlan and is especially common in the north and interior regions where it is based on small hydroelectric dams in the high altitude valleys which supply power to otherwise isolated regions that are too sparsely populated to justify an independent nuclear station and too geographically isolated by difficult terrain to rely entirely on grid connections from elsewhere which could be severed. The mountain dams themselves also serve to regulate the flow of seasonal snow melt and rainwater downstream and supply fresh water to the environs year round.

Electricty from the grid is widely used to power transportation systems such as metros, trams and both passenger and freight trains which have undergone sweeping conversion from diesel to electric over efficiency concearns. Aztapamatlan is an outlier of Oxidentale in that its motor vehicles, namely cars and trucks, continue to operate gasoline and diesel engines as opposed to the electric vehicles commonplace elsewhere on the continent. This is primarily due to the high cost of lithium which makes the powerful batteries of electric vehicles prohibitively expensive for the Aztapaman market. Vehicle owners in Aztapamatlan continue to show preference to gas and diesel powered personal vehicles due to their low cost and longevity compared to expensive electric vehicles which often have a shorter shelf life. Because of this, the scheme of energy used for transport is a mixture of electric powered freight, passenger rail and urban public transportation, contrasted with urban and rural personal transportation which relies more on hydrocarbon fuels. Due in part to this latter demand, some domestic companies have emerged to supply bio-diesel produced from sorghum, corn and miscellaneous plant matter produced by the agricultural sector. Biodiesel has in the past served as an attractive and domestically made alternative to foreign petroleum fuels, particularly when market disruptions cause international oil prices to fluctuate. The biofuels sector also serves to meet demand for heating, which has remained largely based on gas or gas-alternative biofuel rather than the more expensive electric heating alternative.

Transportation

The transportation scheme found across Aztapamataln is heavily influenced by the Calpollist development model that has shaped the expansion of its urban and industrial centers. The main byproduct of the widely dispersed and sprawling urban centers created by the modern industrial Calpolli and the urban society organized around it has been the continued dominance of the automobile for both urban and rural transportation, while the role of metro, light rail and omnibus networks has emerged over the course of the 20th century in the ever expanding urban zones. In general, the sustained outward expansion of the city on the basis of new Calpolli being added to the periphery has fueled the expansion of roadways and auto transport, while the expansion of these networks into already built regions of the city presents greater problems. Therefore, it is in areas of the city which have already been built that mass transit schemes are relied upon to facilitate the movement of workers and other citizens around the city. In order to remain effective, these networks are connected to the newer regions of most cities as well, but are most heavily relied upon in the city centers where traffic congestion is severe and the expansion of expressways or motorways is impractical. Overall, the road network across the CTA has an extent of 377,195 km (234,378 mi) of which 216,822 km (134,726 mi) are paved. Roughly 7% of the total length of roadways in the country consists of multi lane expressways and major arteries for the automotive transportation system which plays a significant role to the overal transit system of the country. Both the roads and railways are nationalized in Aztapamatlan. Most expressways operate on a system of tolls which help to finance their upkeep, while the railways permit the passage of trains owned by private companies on their rail network for a fee for the same purpose. In general, the state ownership model for these means of transportation is regarded as most efficient.

The most extensive network of railways and roadways are the coastal avenues which travel along the relatively flat and densely populated eastern and western coasts. Of the 21 national expressways in Aztapamatlan, 15 are found in the north and west coast regions, with the remainder primarily traversing east to west to connect the two traveling through mountain routes over central and southern Aztapamatlan and the rugged Fishtail peninsula. These expressways are the main means of regional and interregional passenger transportation. The railways are primarily used for freight purposes and serve as the main arteries of non-passenger industrial tranportation, with effectively all Aztapaman goods traveling at some point in their production or distribution through the freight cars of the national rail corporation Tepozcoatl. Two high speed rail lines exist in Aztapamatlan disconnected from one another, these being the east and west coast lines which interlink the major metropolitan centers on each coast and are able to remain financially viable due to the high traffic between these destinations. However, due to much lower density of demand in the interior as well as terrain making it difficult to lay rail for high speed trains, high speed rail has not yet been able to establish itself between the coasts of the country in the interior regions which remain the domain of conventional passenger rail and the motorway system.

Sea links have historically been the lifeblood of the Aztapaman state, due to the difficulty of the interior which made overland travel unfavorable. In the modern day, both sea and air links are grouped in the same non-terrestrial transport category in the CTA, and remain in regular use for travel along the densely populated coasts and between these regions. Air travel in Aztapamatlan is closely regulated by the government but is entirely controlled by private firms making up many dozens of national and regional airlines. There are nearly 1,400 airports in Aztapamatlan and every city above 400,000 inhabitants has a dedicated and modern airport for its service, with domestic air travel making up another large category of passenger travel in Aztapamatlan. However, the eight largest airports in the country corresponding to the five largest cities handle around 90% of all air traffic in the country. By comparison there are 79 seaports in Aztapamatlan, 49 along the west coast and 30 along the eastern coast. Roll on-roll off cargo shipping is commonly used for short range maritime transportation of goods, while major ferry terminals exist in every port city in Aztapamatlan to connect to other ports as well as many smaller terminals along the waterfronts of the same city. Smaller coastal cities and towns are connected by these same maritime passenger and freight transit connections to each other and the major hubs, and in some port cities a portion of commuting workers enter the city from nearby towns or outer wards of the city itself by way of ferry transport rather than rail or road transportation.

Communications

The majority of Aztapaman telecommunication infrastructure is owned by the state corporation Cecnitlacayoh Nuhhuian Macho Huehcacaquiztli Atlepetequipanoliztli (CNMHA), a public utility corporation which enjoyed a total monopoly status between 1925 and 1961 when the sector was liberalized and deregulated to allow private competitors for the first time to establish their own telecoms and broadcasting networks. CNMHA in the modern day has retained its near total monopoly on communications infrastructure in the country, however, and operates using a business model of renting its established equipment out to private networks for a fee which covers the equipment maintenance costs. Aztapamatlan has a state owned internet service provider, Nahuanet, which provides free internet access across the counrty and operates a subsidiary of CNMHA. While many private competitors also offer commerical internet services which are generally faster and of a higher quality, the Nahuanet internet service which is publically available to all residents in the country is considered an indispensable public asset despite its annual losses subsidized by the state treasury. CNMHA telephone, telegraph, faximile and television infrastructure services however are not free to use and the fees the corporation is able to charge to media networks and private companies to use its equipment enables it to generate revenue and effectively cover many of its own expenses without state subsidization while keeping the fees and costs down for the average citizen for basic services as the costs are absorbed by neither CNMHA nor the individual user but rather the private firms paying for the privilege of service on the public system. This model has remained in place for decades thanks in large part to the extensive network of public infrastructure owned by CNMHA the construction of which was paid for by the state, making it more affordable for most private firms to pay the fee to use this network rather than finance and establish their own parallel private networks for their own use. Nevertheless, limited broadcasting stations, especially for radio and television, have been established in large cities like Angatahuaca and Quitzapatzaro where the high density of customers can make the investment into private infrastructure financially sound in the long term.