Svenskbygderna

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

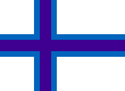

Ecclesiastical Democratic Federation of Pharexia Pharexian: Kirkjulegt Lýðræði af Fharheckx Astellian: Talamh na n-Oileán go Leor | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "To dwell together in unity" Pharexian: "Að búa saman í einingu"" Astellian: "Cónaithe le chéile in aontacht" | |

| File:Pharexia Map Detail.png | |

| Capital | Breíddalsvík |

| Official languages | Pharexian · Astellian |

| Recognised regional languages | Valian |

| Ethnic groups (2019) | 38% Asteillian 23% Mainland Esevær (10% Angshirian, 6% Valian, 3% Eustaki) |

| Demonym(s) | Pharexian |

| Government | Confederal multi-party consociationalist directorial republic with significant elements of direct democracy |

| Hansine Karlson Hans Mathiassen | |

| Legislature | Federal Legislature |

| Ward Assembly | |

| National Assembly | |

| Establishment | |

• Barony of Holafsosan | 1021 |

| Population | |

• 2017 estimate | 2,730,536 |

• Density | 521/km2 (1,349.4/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2017 estimate |

• Total | $130 billion |

• Per capita | $49,451 |

| Gini (2017) | 28.95 low |

| HDI (2019) | very high |

| Currency | Pharexian Sherbornes |

| Date format | dd/mm/yy (NG) |

| Driving side | right |

| ISO 3166 code | PHX |

| Internet TLD | .phx |

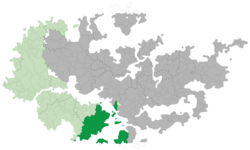

Map of Pharexia (dark green) in the Esevær Alliance (light green) | |

Pharexia, officially the Ecclesiastical Democratic Federation of Pharexia (pronounced: /fərɛziɑ/; Pharexian: Kirkjulegt Lýðræði af Fharheckx pronounced: [kiɒkju:lɛgd l ʁɛ:i af hɑjɛgss], Astellian: Talamh na n-Oileán go Leor pronounced: [ˈfɒːbɔnˀ æˀ kʰʁ̥yˈlænd̥ə], commonly referred to as the Federation of Pharexia or the Pharexian Federation, is a Eseværian nation consisting of the southwestern portion of the Sofjord mainland, the western portion of Djupivogur Island, in addition to several surrounding islands. It shares mainland borders with Fjerholtia to the northwest and Selsoykenia to the southwest. Eastward, across the Passäcaglia Sea, Pharexia controls a small portion of land on the Vivorian mainland which borders Klyasilia to the southeast, the city-state of Trelisfieldia to the northeast, and Susonia to the west.

Pharexia is a semi-direct democratic federal republic. It consists of 21 wards, each with some degree of semi-autonomous devolved administrations. The capital city of Breíddalsvík is located on the northeastern part on the coast of the Passäcaglia Sea. Most of Pharexia’s terrain is flat with the exception of its mountainous border western border; the northern climate is Template:Wpltemperate and covered in deciduous forest while middle and southern Pharexia is largely taiga grassland. Temperatures average between 5°C (41°F) in the north and -1°C (30 °F) in the south throughout the year. As a result of the moderation and the southernly latitude, summers normally hover around 12 °C (53 °F). Average temperatures are -7 °C (19 °F) in winter. The southernly latitude location also results in perpetual civil twilight during summer nights and very short winter days.

Culturally, Pharexia's relatively small population of 2.7 million demonstrates a cohesive national character. This character is attributed to the country’s largely inhospitable southern landscape, the constant darkness of its winters, and the high degree of adherence to the Ilyçisian religion. As a result, Pharexia is a combination of individualism and egalitarianism. Pharexians are highly agreeable and compassionate people, reflected in the state's strong social welfare system, while also harboring conscientiousness and responsibility, reflected by the high GDP per capita, high level of educational achievement, and more recently significant technological advancements.

Pharexia is often described as a unique amalgamation of both conservative and liberal ideologies: for example, despite having rather restrictive abortion laws, it has relatively liberal LGBT+ laws. This dichotomy is usually attributed to the rather unique teachings of the Church of Pharexia, which has both a high adherence and a large influence over public policy. Pharexia maintains a Nordic-like social welfare system that provides universal health care and tertiary education for its citizens. Pharexia ranks high in economic, democratic, social stability, and equality. It is consistently ranked as one of the most developed countries in the world and high on the Global Peace Index. The northern third of Pharexia–home to over half of the country’s citizens–runs almost entirely on renewable energy.

Despite the nation being known for its state of neutrality, this has been questioned in recent years, with Pharexia becoming a member of the Esevær Alliance in 2017. Though Pharexia is philosophically and constitutionally a pacifist country, it continues to maintain a minimal defense force that consists of a coast guard and national guard.

The Pharexian Federation is home to a belief in personal and more recently digital privacy, a high degree of public safety and a complex social insurance scheme mixing private and public funding. Pharexia has strict gun control laws: a national government safety course must be passed, a special license is required to own a handgun which may only be used for target shooting at a licensed range, semi-automatic firearms have caliber restrictions, while fully automatic firearms are banned entirely. Most psychotropic substances, such as alcohol, marijuana, and cocaine, and other class A drugs have been decriminalized but are rarely used. Culturally, Pharexia's attachment to reason and rational thought is evidenced in its constructed language. Astellian is also commonly spoken by Pharexians, and in 1978 it was made an official co-language of the Federation. The Valian language is recognized as a regional language of Eastern Pharexia.

Pharexia has a rather unique relationship with religion–while an overwhelming majority (80%) of citizens are members of the reformed Ilyçisian denomination of Reykjavík, nearly 90% of the population identify as nontheists. The official state church is the Reykjavík Church of Pharexia, which professes that the mainstream monotheistic Ilyçisian God is better conceptualized as a metaphor for a transcendent reality and the relationships that exist between people. The Church of Pharexia rejects the concept of the personal God taught in mainstream Ilyçisianism. Rather, it embraces the cultural and humanistic aspects of Ilyçisianism without their basis in historical events.

Economically, Pharexia is a competitive and highly liberalized, open market economy. Most Pharexian enterprises are privately owned and market-oriented. This is combined with a strong welfare state. Pharexia has generous maternity/paternity leave, government-funded job training, and a free healthcare system. While public spending was estimated to be 25% of GDP in 2019, this percent has been stedily declining for nearly five decades. Public-held debt has more than halved from 50% of GDP to 22%. Much of this is because private companies are now able to provide public goods by competing for contracts alongside public providers (such as in healthcare and education). Since the major wave of liberalization in the mid-1940's, savings haven't changed much and there is still continued debate about if private firms are able to the same quality as public-run services. However, since the fall of the Communist government of Pharexia's state-run economy in 1899, standard of living, life expentency, and self-reported happiness has increased substantially.

Etymology

It is thought that "Pharexia" is derived from an Old Pharexian word for 'mountain healer', a reference to a medicinal herb found in the country's modern-day western border with Selsoykenia. This flower is believed to have been used by native Pharexias to treat influenza, which is known to be an interesting fact used by the tourism industry. The name for “Breíddalsvík”, the capital city, is thought to have come from an old Duxnusaric word for 'wooded', a reference to the city’s former densely forested landscape.

History

Ancient Pharexia (Before 3rd Century CE)

The first recorded settlement of Pharexian territory is Rifjordur (located in modern-day Sojord) around 8000 BCE. Between 8000 and 5000 BCE, early inhabitants used stones to make tools and weapons for hunting, gathering and fishing as means of survival. Primitive structures were eventually erected, indiciating an important shift from nomadism to sedentism. Sheep, moose, and red deer were known to roam freely in the forest and were a common source of food for proto-Pharexians. Agriculture was likely brought to the settlement by invaders from what is now Fjerholtia, as the inscriptions written in the region’s ancient tribal alphabet are found in the area's early agriculture sites. The settlement had evidence of cherry and sheep farms, and there have been cave paintings showing similar animist undertones. These settlements grew in the subsequent years, and around 3000 BCE there were many small settlements dotted around the northern forests and into the upper southern plains.

Neighboring tribes of modern-day Selsoykenia began interacting with the Rifjordur settlement, and the two exchanged knowledge of pottery, agriculture, and it is believed this is what spurred the development of the ancient Astellian language.

Settlements grew quickly in the north regions due to their proximity to the Passäcaglia sea, ease of irrigation for their crops, and the high fertility of the land. The western and southern regions of the country were rocky and cold, and had fewer easily exploited water sources, requiring a higher degree of labor to become farmable. In this time of agricultural development the various bands of people began consolidating into large tribes. The largest and by far most well known of these was the Angshire tribe, who developed the first nation state of Pharexia. Through a series of conquests and marriages the Angshire tribe would come to control all of what they considered to be their homelands.

The Angshire Era (late 7th century to 1600 CE)

Under the rule of the Angshire family, a feudal system was implemented which the royal family would lease land to roughly 100 wealthy families and would give them the title of lord families. These lord families would then lease lands to baron families who would lease them to peasants. Due to the Passäcaglia Sea that seperated the two nations, Pharexia was largely spared from Klyasilian invasions, as the Klyasilians had only very small, rudimentary boats.

However, around 800 CE, a large army of invaders from the Valian Kingdom successfully annexed most of northern Pharexia, ending the Angshire family's 300 year claim to the region. At this point in time, the Valian Kingdom covered most of the Sofjord mainland. A major civil war broke out in the Valian Kingdom in 951CE when King Teodaria III's twin sons fought for the right to rule. The war resulted in the death of Prince Gallio and began the reign of King Litio I.

Industrial Pharexia (1600 to 1900 CE)

Early Modern Pharexia (1543 to 1898 CE)

Modern Pharexia (since 1898 CE)

Geography

Climate

| Pharexia | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Climate chart (explanation) | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Nature

When Pharexia was first settled, it was extensively forested, with 80% of the original land covered in trees. In the late 17th century, permanent human settlement had greatly disturbed the isolated ecosystem. The forests were heavily exploited over the centuries for firewood and timber. A 1987 government assessment found only 12% of the original forests remained. Deforestation, climatic deterioration, and overgrazing by livestock imported by settlers caused a loss of critical topsoil due to erosion. The issue has recently gained significant attention at the state and federal level. The left-wing environmentalist political party Green–Left has put forth several legislative proposals in recent years to halt all remaining logging operations in Pharexia and require all raw wood be imported. The ruling Conservatives, while criticizing the proposal as "impractical" and "anti-business", have passed legislation requiring logging companies to replant two trees for every one they cut down.

Government

Pharexia is a federal multi-party directorial republic, consisting of 21 different subdivisions known as wards. The country's government is based on the 1900 constitution, People's Law (Pharexian: Folkslov, Astellian: Qunnerit), which defines how the government's branches work and how they interact with one another and protects the civil rights of the population. Amendments to the constitution require a 75% majority in the Federal Legislature or the approval of 13 out of 21 wards, accompanied by a public referendum. The constitution has only been amended four times, in 1905 to abolish the death penalty, in 1964 to change the Federal Legislature from a plurality-based system to STV, in 1977 to change the Federal Council from 5 members to 6 and enshrine Pharexia's universal healthcare system, and in 2017 to add a seventh and eighth position on the Federal Council. There are three major branches of the federal government: the bicameral Síðari/Félagið (legislature), the eight-member National Council (executive), and the Lagâleg Court of Justice (judicial).

Executive

The Federal Council (Pharexian: Sambandsríki, Astellian: Cónaidhme) is the executive branch, consisting of eight councilors. One of the councilors is labeled as the ceremonial Head Councilor (Pharexian: Seansailéir, Astellian: Ceannasaí) for the year, and another is labeled the Vice Councilor (Pharexian: Seasmhack, Astellian: Staðgengill). Each member except the Head Councilor is in charge of one of Pharexia’s seven large government departments dealing with broad policy fields. The Council itself is based on ideas of consociationalism, in which the main political parties of Pharexia share out the seats within the council, a tradition that has been maintained since the beginning of the country and relies on pragmatism between the parties. Currently, the Conservative Party and the Science–Moderate Party hold two sets each while the Ilyçisian Democrats, Liberal Party, and New Future hold one seat each. One member of the Council is unaffiliated.

Legislature

Legislative power is vested in the bicameral Federal Legislature (Pharexian: Síðari, Astellian: Félagið). The lower chamber is the 274-seat People's Assembly (-), and the upper chamber is the 63-seat States' Assembly (-). The houses have identical powers. Members of both houses represent the states, but, whereas seats in the National Assembly are distributed in proportion to their population using open-list proportional representation, each state has three seats in the States' Assembly, which are elected using single transferrable vote. Both are elected in full once every four years on the 1st March, with the last election being held in 2018.

The Federal Legislature possesses the federal government's legislative power, along with the separate constitutional right of citizen's initiative. For a law to pass, it must be passed by both houses. The Federal Legislature may come together as a United Great People's Legislature in certain circumstances such as to elect members to the Federal Council and justices to the High Court of Justice.

Judicial

The judicial branch plays a minor role in politics, apart from the High Court of Justice (Pharexian: Réttlæti, Astellian: Lagâleg), which can annul laws that violate the freedoms guaranteed in the constitution. The Federal Legislature, in a joint session, creates a list of legislative appointees to the High Court, with the Federal Council choosing from that list.

Political Parties

| Party Name | Seats in the Ward Assembly | Seats in National Assembly | Seats on the Federal Council | Ward Executive Council Seats | Position | Ideology | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Conservative Party Stéttarfélags |

18 / 63

|

61 / 277

|

2 / 8

|

26 / 96

|

Centre-right | Liberal-conservatism, Economic liberalism | |

| Science–Moderate Party Šísindasveit |

15 / 63

|

42 / 277

|

2 / 8

|

17 / 96

|

Centre | Technocentrism, Third way | |

| Liberal Party Frjálslynda réttlæti |

9 / 63

|

33 / 277

|

1 / 8

|

13 / 96

|

Centre-left | Classical liberalism, Social progressivism | |

| Ilyçisian Democrats Ilyçieoan aðila |

6 / 63

|

28 / 277

|

1 / 8

|

10 / 96

|

Right-wing | National conservatism, Right-wing populism | |

| New Future Framtíðinni |

8 / 63

|

17 / 277

|

1 / 8

|

14 / 96

|

Centre-right | Agrarianism, Decentralization | |

| Greens–Left Græn-vinstri |

5 / 63

|

20 / 277

|

0 / 8

|

6 / 96

|

Centre-left to left-wing | Green politics, Social democracy | |

| Dignity–Solidarity Party Reisn–Verç |

2 / 63

|

8 / 277

|

0 / 8

|

4 / 96

|

Left-wing to far-left | Anti-capitalism, Secularism | |

| Moderate Party Hófleg |

0 / 63

|

22 / 277

|

0 / 8

|

2 / 96

|

Centre | Economic liberalism | |

| Forward Áfram |

0 / 63

|

11 / 277

|

0 / 8

|

1 / 96

|

Right-wing to far-right | Anti-immigration, Economic nationalism | |

| Lofogengenlok Independence Sjálfstæðismenn Lofogengenlok |

0 / 63

|

8 / 277

|

0 / 8

|

1 / 96

|

Left-wing | Regionalism | |

| Unaffiliated Óaðstoð |

0 / 63

|

27 / 277

|

1 / 8

|

14 / 96

|

N/A | N/A | |

Wards

Pharexia is currently divided into 21 administrative regions called wards (Pharexian: rijords, Astellian: bharda), which assist with the institutional and territorial organization of Pharexian territory. There are currently four types of wards: states, free cities, territories, and autonomous regions. A ward’s classification is based on its autonomy from the federal government. States–which make up 15 of the 21 wards–have devolved legislatures and their own 5-person executive council, akin to the Federal Council’s structure. States are able to legislate on all subjects that are not reserved matters of the federal government. Free cities (such as the capital city of Breíddalsvík) have a singular executive but lack a legislature and a full executive council, and thus rely on the Síðari/Félagið to pass legislation. Gæcadoia, currently the only ward currently classified as a territory, has neither an independent executive or legislature and is administered by a federally appointed viceroy. Finally, Lofogengenlok is the only fully autonomous region and self-governing part of Pharexia, officially deemed as such after the 1934 Pharexian–Lofogengenlok reunification. Lofogengenlok, originally a Pharexian ward, had in 1521 declared itself an independent country. While Pharexia never officially recognized this claim, Pharexian foreign policy had largely treated it as a separate country until negations warmed during the Second Great War. As of 2020, Pharexian national law does not generally apply in the region and Lofogengenlok is treated as a separate jurisdiction, although there is continued debate regarding its independence. It’s head of state is currently Queen Melisende III, and Lofogengenlok has its own legislature, the Legcø.

| Ward | ID | Population # | Head Executive/Party |

|---|---|---|---|

| BE | - | Tarja Vänskä | |

| BR | - | Heike Reynder | |

| CE | - | Arsenio Ratti | |

| DY | - | Moise Pisani | |

| FE | - | Tuomas Mustonen | |

| GC | - | Benedikt Svenson | |

| HA | - | Ferdinanda Orsini | |

| HE | - | Katharen Anadottir | |

| HV | - | Asløg Jennýsdottir | |

| LK | - | Ragnhild Ernadottir | |

| LO | - | Queen Melisende III | |

| LV | - | Ofelia Ratti | |

| MA | - | Francois De Ouserad | |

| OS | - | Luciana Ardiconi | |

| RG | - | Severo Acardi | |

| SA | - | Anna Takala | |

| SJ | - | Rasmus Beck | |

| SO | - | Kirsikka Peura | |

| ST | - | Nikolaj Jonson | |

| TR | - | Tua Farver | |

| VO | - | Uwe Matthiessen |

Defense

The military of Pharexia consists solely of the Coast Guard (Pharexian: Varnirliðið, Austellian: Glijbaan) which patrols Pharexian waters. The country is one of few who has no standing army.

The Coast Guard is based upon a small core of professional volunteers. If necessary, it can field up to 200,000 soldiers of fighting age in the case of a ground invasion. For obvious reasons, this is unsustainable in any other situation, and so the regular strength of the Coast Guard is closer to 20,000 professionals and militia. The military's role is purely defensive. They have yet to engage in battle either overseas or within the Pharexia.

Economy

Infrastructure

Transportation

Transportation in Pharexia is facilitated by road, air, rail, and waterways (via boats). The vast majority of passenger travel occurs by cycling or automobile for shorter distances, and railroad or bus for longer distances.

Driving in Pharexia is a frequent occurrence, with approximately 60% of Pharexians owning private automobiles. Each ward has the authority to set its own traffic laws and issue driving licenses, although these laws have largely been the same since the 1960's. Licenses from other state are respected throughout the country. Pharexians drive on the right side of the road. There are numerous regulations on driving behavior, including speed limits, passing regulations, and seat belt requirements. Driving while intoxicated with alcohol or marijuana is illegal in all jurisdictions within Pharexia.

Most roads in Pharexia are owned and maintained by either the federal or ward governments. National Highways (Pharexian: Ajóðveginum, Austelliann: Mhórbhealaigh), defined as controlled-access roads spanning 2 or more states, are federally maintained and subject to federal regulations. Expressways–controlled-access roads existing entirely within a single state–are built and maintained by the state and are likewise subject to regulations set forth by the state. In addition, there are many local roads, generally serving the many of the remote or insular locations of southern and western Pharexia.

Cycling

Cycling is a common mode of transport throughout Pharexia, with 45% of the people listing the bicycle as their most frequent mode of transport on a typical day as opposed to the car by 38% and public transport by 21%.

Energy

Water supply and sanitation

Communications

Healthcare

Pharexia has a single-payer, universal healthcare system. The system was adopted in 1970 as a part of the creation of the welfare state in Pharexia. It is managed centrally by the Councilor of Health and Social Care, and at the local level by 43 health boards elected every five years by the general populace.

The healthcare system is funded via federal income tax, and it is the largest recipient of money from the federal budget, with around 10% of the entire Pharexian GDP being spent on healthcare. This funding has led to an efficient, well-maintained, well-staffed healthcare system free at the point of use. PHS is thus admired by many, and recent polls in Pharexia have shown that over 85% of the population is supportive of the system.

Mental health has received increased attention in Pharexia in recent years, with mental health funding being increased in response to increased openness around mental health in Pharexia. Recent research has found that significant proportions of Pharexians suffer from conditions such as depression and anxiety.

Education

Demographics

Language

Religion

Formal religious affiliation in Pharexia (2020)

For much of Pharexia's history, Ilyçisianism has dominated the public and private sphere of daily life. The Reykjavík Church of Pharexia (Pharexian: Kirkja hins af Fharheckx, Austellian: Séipéal n-Oileán naofa), often abbreviated as the KHF) is both the established church in Pharexia as well as the largest denomination of Ilyçisianism, with nearly 60% of the population reported as members. There are smaller Reykjavíkian churches unaffiliated with the Church of Pharexia that make up an additional 15%. Reykjavík and Ilyçisianism have a complex theological, historical, and sociological relationship. While Reykjavík (Reformed) Ilyçisians consider the Endurreisn Heimsins to be scripture, they do not believe in inerrancy or literalism like most Sólheimaka (Orthodox) Ilyçisians do.

Reykjavík theology argues that interpreting Ilyçisian scripture must be informed by scholarship (particularly from psychological, evolutionary, and existential perspectives). Perhaps the largest distinction is that most Reykjavík do not profess a belief in a celestial being. Rather, Reykjavíkians believe that theism has lost credibility as a valid conception of God's true nature. Such a belief is commonly referred to as Ilyçisian atheism. Ilyçisian atheism is a form of cultural Ilyçisianism and ethics system drawing its beliefs and practices from Addindr’s life and teachings as recorded in the Endurreisn Heimsins and other sources, whilst rejecting supernatural claims of Ilyçisianism. In 2005, the book Believing in a God Who Does Not Exist: Manifesto of An Atheist Minister, Reykjavíkian pastor Hendrikse describes that Reykjavík Ilyçisians believe "God is for me not a being but a word for what can happen between people. Someone says to you, for example, 'I will not abandon you', and then makes those words come true. It would be perfectly alright to call that [relationship] God". Hendrikse's views are widely shared among both clergy and church members. Some–especially Sólheimaka Ilyçisians–view the Reykjavíkian denomination as distinct enough from traditional Ilyçisianism so as to form a new religious tradition, although the KHF rejects this claim.

The second largest Ilyçisian denomination in Pharexia is Sólheimaka. Sólheimakans are orthodox Ilyçisians in the sense that they continue to believe in an actual heavenly God, as well as Endurreisn Heimsins literalism. The Church of Sólheimaka is the largest Sólheimaka church in Pharexia, with nearly 8% of Pharexians considering themselves members. An additional 2% are members of smaller, independent Sólheimakan churches.

In total, all Ilyçisians of both the Reykjavík and Sólheimakan denonination make up around 83% of the population. Their distribution is spread relatively equally throughout the country. With the exception of southern Pharexia (~95%), and Breíddalsvík (~45%), the average number of Ilyçisians in each ward stands at approximately 8-in-10.

Among people who identify as Ilyçisians, 50% of them attend weekly religious services, a figure much higher than other religious people in the country. Reykjavík Ilyçisianism is typically classified as a liberal denomination. For example, the Church of Pharexia has long supported gay and lesbian rights. Weekly Reykjavík services do not revolve around worship but rather focuses on deconstructing ancient scripture to extract out philosophical, ethical and theological wisdom that can be applied to the modern day. There is also a strong emphasis on community and fellowship.

Religion continues to play a significant role in the debate over abortion and physician-assisted suicide in Phareixa. The official Church of Pharexia stance is, "Life, the experiences we gain from being a part of the world and of humanity, are necessary and essential to spiritual fulfillment." This position is shared by most Ilyçisians. The Conservative Party, Science–Moderate Party, New Future, and the Ilyçisian Democrats all oppose abortion and cite Ilyçisian values as their justification.

While Reykjavík Ilyçisianism is officially the state religion, People's Law (Pharexian: Folkslov, Austellian: Qunnerit) guarantees religious freedom and upholds equality, no matter one's religious affiliation. In the last census, only 12% of the population identified as having no religion, despite nearly 80% of the country answering that they "do not believe there is any sort of spirit, God, or life force". This strangely makes Pharexia one of the most religious and secular countries in the world. A released in 2016 indicated that only 42% of Pharexians would vote for an openly theistic candidate. This is up slightly from 36% and 40% in 1987 and 1999 respectively.

According to a 2016 poll:

• 8% of Pharexian citizens responded that "they believe there is a God".

• 16% responded that "they believe there is some sort of spirit or life force".

• 62% responded that "they don't believe there is any sort of spirit, God or life force".

• 14% gave no response.

According to 2018 data from annual social-cultural study, 40 percent of Pharexians responded with "No" to the question to the question "Do you believe in God?", while 6 percent said "Yes" and 54 percent said that either they did not know or that the question was “difficult to answer”. Follow up questionares have found that while over 80% of Pharexians do not believe in a "literal, celestial supreme being", nearly 75% believe that they believe in a "higher order or calling" that is "synonymous with the idea of God". The survey also showed that 7-in-10 Pharexians say religion is an important part of their lives, which is notably higher than other developed nations.

Ethnicity

Racial Makeup of the Pharexia (2015 census)