List of Themiclesian monarchs: Difference between revisions

| (21 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

The following is a near-complete list of all monarchs who have ruled as sovereigns of Themiclesia. | The following is a near-complete list of all monarchs who have ruled as sovereigns of Themiclesia. | ||

== | ==Pre-treaty== | ||

{| | {{see also|Treaty of Five Kings}} | ||

===Tsjinh patriarchs=== | |||

The ''[[Springs and Autumns of Six States]]'', writting around the 4th century CE, provides a long list of known monarchs of all the states in Themiclesia during the [[Hexarchy]]. Though accepted as historical canon, they have been considerably revised by unearthed texts and historical research. | |||

The ''Six States'' lists 32 "patriarchs" (徹先伯), conventionally interpreted as leading figures in the lineage of the Tsjinh ruling house. The first ten figures are conventionally thought to be mythological figures. First, their names recapitulate the ten-member {{wp|heavenly stem}} sequence in order, which contrasts with the 22 following names, where there are no sequences at all. Second, the ''Six States'' provides that they were ten members in a single generation, which the maximum elsewhere is five after each other. Third, their names are never mentioned in the [[State cult of Themiclesia|cyclical sacrifice]] oracles, which record the list of venerated parriarchs almost unerringly. Finally, anthropologists think the first ten rulers were imagined by later writers as a rationalization for the Tsjinh clan's original kinship structure, forgotten in later ages because it was either overthrown or fell into disuse, never written down in either case. | |||

From the figure of High P.rjang′, the lineage becomes less problematic. A considerable number of scholars think that High P.rjang′ is the first historical figure in the Tsjinh lineage, though his whereabouts and activities are unknown. Some date him to the 8th or 9th century BCE, though others believe even an approximate date cannot be established, since his biological relationship with the succeeding members of the list is uncertain. The historical part of the lineage is reconstructed by comparison between oracular plates. In the 19th century, the veracity of the earlier part of the lineage was placed under question, despite their similarity to oracular charges to lists of ancestors. However, as more caches of oracular inscriptions were found, it was discovered that many lineages converge towards a common ancestry. For example: | |||

{| class="wikitable" | |||

!style="width: 5em"| Generations !!style="width: 5em"| 1 !!style="width: 5em"| 2 !!style="width: 5em"| 3 !!style="width: 5em"| 4 !!style="width: 5em"| 5 !!style="width: 5em"| 6 !!style="width: 5em"| 7 !!style="width: 5em"| 8 !!style="width: 5em"| 9 !!style="width: 5em"| 10 | |||

| | |||

| | |||

! | |||

| 1 | |||

| 2 | |||

| 3 | |||

| 4| | |||

| 6 | |||

| 7 | |||

! | |||

! | |||

! | |||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! Lineage 1 | ||

| P.rjang′ || ′Rjut || Njem || Têng || Krap || Kje || P.rjang′ || ′Rjut || K.rang || Têng | |||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! Lineage 2 | ||

| P.rjang′ || ′Rjut || Njem || Têng || Krap || Kje || K.rang || Kwji′ || P.rjang′ || ′Rjut | |||

|- | |- | ||

! | ! Lineage 3 | ||

| P.rjang′ || ′Rjut || Njem || Têng || Krap || Kje || K.rang || Kwji′ || P.rjang′ || Sjin | |||

|} | |} | ||

In this case, lineages 1 and 2 would be said to converge at the sixth generation, and lineages 2 and 3 at the ninth, where the identity of their respective ancestors are considered too remote to be a sheer coincidence. The main lineage most similar to that recovered from historical documents is attested on over 54 separate instances, making the matter "virtually beyond question" in an age where there is very little evidence of mutual contact between diverging branches of the family, beyond a cultic context, or motivation to create a common ancestry. This conclusion is further buttressed by archaeological dating of the sites where these lineages are recovered. | |||

There is a degree of variance between the oracular and ''Springs and Autumns'' record prior to the reign of [[P.rjang'|Pêk]]. It begins to record historical events for Tsjinh state beginning in his reign. The motivation of this historiographic change is still unclear, but it seems connected to a century of instability in the lineage, changes to succession rules, and the nature of Patriarchship. It has been argued by some that the author of the ''Springs and Autumns'' was not aware of a collegiate nature of Patriarchship before Pêk's reign, thus the omission of certain figures found in the oracular record, which may still have been available in the 4th century. | |||

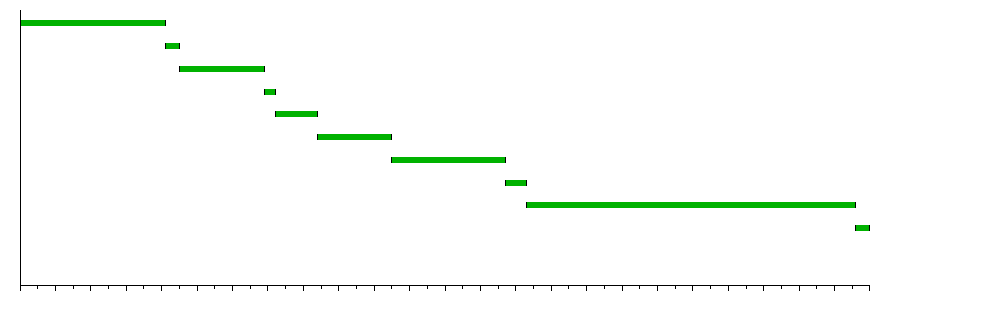

==Modern timeline== | |||

<timeline> | <timeline> | ||

ImageSize = width:1000 height:auto barincrement:25 | ImageSize = width:1000 height:auto barincrement:25 | ||

| Line 111: | Line 79: | ||

==See also== | ==See also== | ||

*[[Themiclesia]] | *[[Themiclesia]] | ||

==Notes== | |||

<references /> | |||

[[Category:Themiclesia]][[Category:Septentrion]] | [[Category:Themiclesia]][[Category:Septentrion]] | ||

Latest revision as of 06:33, 13 April 2021

The following is a near-complete list of all monarchs who have ruled as sovereigns of Themiclesia.

Pre-treaty

Tsjinh patriarchs

The Springs and Autumns of Six States, writting around the 4th century CE, provides a long list of known monarchs of all the states in Themiclesia during the Hexarchy. Though accepted as historical canon, they have been considerably revised by unearthed texts and historical research.

The Six States lists 32 "patriarchs" (徹先伯), conventionally interpreted as leading figures in the lineage of the Tsjinh ruling house. The first ten figures are conventionally thought to be mythological figures. First, their names recapitulate the ten-member heavenly stem sequence in order, which contrasts with the 22 following names, where there are no sequences at all. Second, the Six States provides that they were ten members in a single generation, which the maximum elsewhere is five after each other. Third, their names are never mentioned in the cyclical sacrifice oracles, which record the list of venerated parriarchs almost unerringly. Finally, anthropologists think the first ten rulers were imagined by later writers as a rationalization for the Tsjinh clan's original kinship structure, forgotten in later ages because it was either overthrown or fell into disuse, never written down in either case.

From the figure of High P.rjang′, the lineage becomes less problematic. A considerable number of scholars think that High P.rjang′ is the first historical figure in the Tsjinh lineage, though his whereabouts and activities are unknown. Some date him to the 8th or 9th century BCE, though others believe even an approximate date cannot be established, since his biological relationship with the succeeding members of the list is uncertain. The historical part of the lineage is reconstructed by comparison between oracular plates. In the 19th century, the veracity of the earlier part of the lineage was placed under question, despite their similarity to oracular charges to lists of ancestors. However, as more caches of oracular inscriptions were found, it was discovered that many lineages converge towards a common ancestry. For example:

| Generations | 1 | 2 | 3 | 4 | 5 | 6 | 7 | 8 | 9 | 10 |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lineage 1 | P.rjang′ | ′Rjut | Njem | Têng | Krap | Kje | P.rjang′ | ′Rjut | K.rang | Têng |

| Lineage 2 | P.rjang′ | ′Rjut | Njem | Têng | Krap | Kje | K.rang | Kwji′ | P.rjang′ | ′Rjut |

| Lineage 3 | P.rjang′ | ′Rjut | Njem | Têng | Krap | Kje | K.rang | Kwji′ | P.rjang′ | Sjin |

In this case, lineages 1 and 2 would be said to converge at the sixth generation, and lineages 2 and 3 at the ninth, where the identity of their respective ancestors are considered too remote to be a sheer coincidence. The main lineage most similar to that recovered from historical documents is attested on over 54 separate instances, making the matter "virtually beyond question" in an age where there is very little evidence of mutual contact between diverging branches of the family, beyond a cultic context, or motivation to create a common ancestry. This conclusion is further buttressed by archaeological dating of the sites where these lineages are recovered.

There is a degree of variance between the oracular and Springs and Autumns record prior to the reign of Pêk. It begins to record historical events for Tsjinh state beginning in his reign. The motivation of this historiographic change is still unclear, but it seems connected to a century of instability in the lineage, changes to succession rules, and the nature of Patriarchship. It has been argued by some that the author of the Springs and Autumns was not aware of a collegiate nature of Patriarchship before Pêk's reign, thus the omission of certain figures found in the oracular record, which may still have been available in the 4th century.

Modern timeline