Caste System in Benaajab

The caste system in Benaajab is an example of religiously dominated unfree labor. It originates in the combination of many different societies when they were first unified under the rule of Gautama Empire at the turn of the first millennium BCE. When trying to control the diverse communities under their control the Gautama Emperors devised the Srama system to organize labor universally.

Origins

The first Gautama Maharajas ruled with a light hand, preferring only to reap the vast tributes paid to them from their subject kingdoms. In 102, Maharaja Badri moved the capital from Santosa--where the previous maharajas had sat--and began to construct an imperial palace in Kumar, where his chief wife was from. In order to achieve this, he brought with him fifty-thousand artisans and laborers who were a part of the imperial estates in Kanca. The workers, who were mostly native tribesmen from Dhaka, however, often tried to escape or would not work. At first Badri tried to control the enormous workforce by sending his courtiers out as overseers, but the famously cruel methods of the courtiers only intensified dissatisfaction and ultimately produced (an unsuccessful) rebellion in Kumar. After the revolt was put down, the Conclave of Teachers convened and ordered the Maharaja to use Kumari natives to build his palace since the revolt was clearly a sign that he had upset the balance of the population too much. The workers returned home to Kanca, though many families in Tsnarta are related to these workers.

Maharaja Badri, unable to afford to continue the project paying for wages as well as the materials, instituted the first example of organized Srama labor. He organized Kumar into four groups: aristocrats (who already paid a tribute to the throne); artisans, who worked with the producer of other men; those who worked the land; and those who did not work the land. Each group was required to donate a small portion of their time to palace project.

This kind of system was not abnormal for Benaajab in general or Kumar in particular, but normally it was up to each community what work they needed from their members. Typically a town or village group of elders would organize working groups to maintain roads, build houses for elderly, or otherwise fulfill important social duties. Likewise each village would serve some essential purpose for their local aristocrats; one village might build a mill, another might provide produce for a set number of days. All of these duties were, however, based on the particular needs of the community rather than the individual's particular skill set. Since the palace was, fundamentally, a superfluous project, Badri could not require the city of Kumar to build it for him since that too would violate his Dharmic duty. By taking from each class what each class had in abundance, Badri was able to circumvent tradition and substantially increase the importance of the central government. The Conclave of Teachers, which was allowed to forgo service in Srama, later ratified the Maharaja's decision.

This shifted the balance of power all over the empire from local elders to local aristocrats, who previously functioned more as tax collectors and city managers. After the establishment of Srama, however, the aristocratic class was able to more closely control what their subjects did.

Participation & Outcasts

Participation in Srama is not mandatory, but being expelled from a caste can have many negative consequences. Once expelled, an individual (or more often an entire family) can be cut off from public services, including access to the legal system. People outside of Srama are often forced to take the least desirable work, such as selling themselves into slavery. Slavery is one of the only ways to re-enter Srama and even now, while slavery is outlawed, families secretly enslave their children to regain their social status.

Sometimes, to avoid humiliating someone, a community will offer a family a special service that, if performed over a specified period, will wipe out the expulsion. Sometimes this means filling some kind of niche or incidental need; giving children to the priesthood or digging wells are common "light" sentences. In a more extreme, a family was ordered to prostrate themselves at the steps of the temple and let people step on them on their way in. These punishments are typically at the discretion of a local aristocrat or priest and is often abused where still allowed.

Members of most castes are encouraged to intermarry and marrying outside of a caste can be grounds for punishment. Each caste also has unique social functions, holidays, and mythic heroes.

There is no one warrior caste or group. Soldiers come from everywhere and every level of society, but each has its own military tradition and has historically served a special role. The Khadya, which was historically the most numerous caste, served as infantry and a mix of Khadya and Gathana acted as the cavalry. Udyama, who owned a substantial time debt (rather than materials) and were therefore more available, often acted as a police force in peacetime.

Public Labor

Sometimes, when a family has been outcast for a long period of time, the only way they can reenter society is through the Rastaya, the road people. The Rastaya is also called "public labor" or the underslave class by the Mutulese. The Rastaya have very few rights and considered the slaves of everyone else in the Srama system; unlike the bonded labor of the Udyama who have a professional relationship with their bondsman.

Rastaya were an easily abused class of people, often the subject of physical violence. They would often be given duties as a public service, such as cleaning streets or lighting public buildings, by their lords. These duties could be added on to by anyone who came into contact with the Rastaya, often taking them away from their assigned work and leading to a build of "work debt" that would keep them in the public labor class indefinitely. The only hope for escape was to marry into another caste or, more often, simply live a long ways away from anyone who could add onto the work debt. The Rastaya often build enclaves far from other villages and would only be seen on the road, leading to their name.

The Rastaya class was officially disbanded by the Mutul and Rastaya communities were elevated to official village status so that they could participate freely in society. Former Rastaya villages and individuals are, however, still heavily discriminated against despite national-level programs to better integrate them. The Rastaya were often accused of forming gangs that would rob merchants or travelers who came too close to their villages, which has contributed to a stereotype of criminality and laziness.

Tulotairi

Tulotairi, or Cotton Men, was the name given to the natives Benaajabi serving at first in the militias maintained by the Nuk Nahob, the Mutuleses Trader Guilds, and then as official soldiers in the Mutuleses armies. The Tulotairi were often Outcasts, Rastaya, and impoverished Khadya fleeing their conditions. While at first a derogatory term used because of the Cotton uniforms they wore, the Tulotairi started to use the term themselves, until it became a synonym of the auxilliary corps.

After the disbanding of the Rastaya class by the Mutul following the end of the First Bandhaśēka Rebellion, numerous Rastaya communities and families started to dedicate themselves entirely to warfare and the military and the professionalisation of the Tulotairi started during the Rebellion continued long after. This also had its consequences, as numerous Rastaya communities ended up leaving their old enclaves for new villages built around Mutuleses caserns and fortress. The old enclaves were then generally sold to Khadya who used new Oxidentaleses crops to cultivate these lands that were often too poor or not adapted to more traditional cultures, which was the reason why they had been abandoned to the Rastaya in the first place.

The Tulotairi were also a vector of "Oxidentalisation" for the Benaajabi society. To avoid persecution and to better rise through the ranks of the Och'kak military, they often started worshiping Mutuleses gods, notably Chaac, which was associated with the cult of the K'uhul Ajaw, but also of Buluc Chabtan, god of violence and war. Through them, and the merchants, Oxidentalese practices, beliefs, and scientific knowledge, reached Benaajab and fused with existent knowledge.

the Tulotairi were part of a melting pot that the Mutul inadvertently created that helped reduce the barriers between the different regions, and helped the creation of a "Benaajabi" identity without consideration of the previous petty principalities and kingdoms. However, they found themselves to be “outcast” again as the lack of memories on their ancestors classes and their service of the Mutuleses put them at odds with the independentists they helped repress. After the independence of the country, the Tulotairi were used by the Monarch of Benaajab as the basis of the military of the new country.

Today, the Tulotairi as a social distinction or even military term is gone. However, numerous prominent military families continue to claim to have Tulotairi ancestry. As such, some observers have theorized the existence of a “neo-tulotairi” caste which has a lot of influence over the modern military of Benaajab, especially its Army.

Types of Srama

Niranjan

The so-called "pure" caste is a reference to duty: all of the people in the Niranjan caste already serve an essential service to the Dharmic world-order and are therefore exempt from the additional duties to the state or society. Priests, aristocrats, and those who care for the dead are all venerated positions in society and are included in the Niranjan. Upsetting the balance of society or following some anti-Dharmic credo are grounds for expulsion from this class. Aristocrats who force their subjects to rebel, priests who teach wrong theology, or grave-diggers who allow their communities to become infected with disease are all examples of grounds for expulsion.

Male members of the Niranjan are discouraged from marrying within their caste, since this would place too much responsibility on one family. Since most priests already do not marry, they are the primary proponents of this law and are careful to approve marriages that they feel might upset the balance of duties across society. This rule is often circumvented by demoting close family members to a lower caste and then marrying them off to a fellow aristocrat; though if it is found out, it can result in an entire family being expelled from their caste.

Udyama

The Udyama is typically the wealthiest class since they were lavished whatever gifts they wanted by their lords. They were required to set-aside a substantial amount of their time for their lords, but ultimately had a much easier existence than anyone else. This class was made up of weavers, smiths, scribes, and other laborers who were directly involved in manufacturing goods from other goods.

They were not allowed to produce goods for trade, but they were allowed to manufacture cloth, metalwork, and literature for themselves and their lord. Anything that they produced in surplus would be handed over to the Gathana for trade. This class could not own most of their work, but since they provided the most important services to their lord, they were well taken care of.

There are two types of Udyama; bonded and unbonded. Those who are "bonded" are slaves, though they have some protections of their rights, all of their time and labor is owed to their bondsman. The unbonded class still owes some of their time to local aristocrats, but retains a great deal of time to devote to their own private projects.

Gathana

The Gathana is a large caste that includes anyone who does not work the land. Historically, this caste was made up of miners, foresters, sometimes herders (depending on whether they own the land), and traders; each group forming their own sub-caste. While they cannot own land, they are allowed to own and trade the produce of others. Whatever surplus of crops, for example, which was left over in the community would be handed over the Gathana tradesmen. Miners were the primary entrepreneurs historically, since they could sell ore to aristocrats and were essentially allowed to own everything that they had (except land).

There are two kinds of Gathana; soft and hard. Soft labor is composed of perishable goods, such as food or drink, while hard labor is concerned with metals, masonry, or textiles. The hard labor is typically the wealthier faction.

Khadya

The Khadya, the sustenance, are the only caste that is allowed to privately hold land. They might not buy or sell land, but can be given land by their local lord, who must ensure that all land is given away. While they may own land and decide what to grow, who to employ, and many other details, they do not own their produce. Whatever the land produces (beyond what is consumed by the Khadya themselves) is returned to the lord, who distributes it to his own household and the rest of the community.

Because of their unique right to own land, there is a special Khadya appointed for every public building, including mansions and aristocrats, where they act as the household administrators or landlords in the case of housing for non-Khadya.

The Khadya is divided into land-owning farmers/grazers and those who work on land they do not own. Farmers are always Khadya, but herders who do not own their land are a special caste of Gathana. This is especially important since no one person can own both the livestock and the land on which they graze.

Modern Srama

It is possible to be successful, even wealthy, as a member of any caste, but the social expectations definitely allow some groups to achieve greater status more quickly. Since all of the castes are based on reciprocity with other castes, social expectations can be extremely important even in modern business dealings. It is expected, for example, that a Gathana should sell his stock to an Udyama at a discount, which often keeps Udyama-owned businesses more more profitable than a comparable Gathana or Khadya organization.

The state mostly tried to combat this inequity through its small business lending program, which offers more favorable rates businesses formed by a member of one caste that operates in the traditional sphere of another caste. Cross-caste education is also encouraged and caste is a protected status.

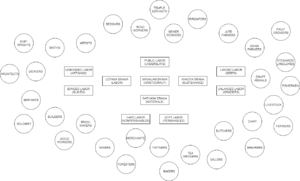

Distribution

The sub-groups of the Srama, which are often called Suta (সুতা, lit. "threads"), are craft-specific kinship-groups that vary across Benaajab. There are eight ethnic regions of Benaajab which have a generally consistent view of different lineage groups and professional pursuits.

In Ora, because of the mixture of Azdarin, Zoroastrians, and Zensunnis, religion is the most important indicator of social status and form the most important endogamous groups. Additionally, Ora is substantially more economically liberalized than most of Benaajab, which helps to relieve pressure on all social groups, especially professional Suta. Because each of the three major groups of the Orese Region are endogamous, lineage is incorporated into names as an indicator of standing within each group; names typically employ a string of patronymics in addition to surnames and given names. Because of the high urbanization along the coast of Lake Dhaka, however, the Khadya families that own urban housing developments have formed an aristocracy unto themselves.

Silkutha is the least populated region of Benaajab, which allows it to operate on the basis of patronymic surnames. Tribal affiliations, always present in surnames, will consistently represent social status in the highlands. The most important groups in Silkutha belong to the grazier professional sect of the Khadya caste.

Mata is the north and central mountainous region. Mata is the most religiously unified region in Benaajab. As a result of this religiosity, the Matese Region has the most intense adherence to caste law. Marriages are overseen directly by local priests and the castes are kept in rigid order.

The riparian heartland of Benaajab, Medhinpur, has the largest population of any region and best represents the quintessential caste behavior. A mix of kinship groups and profession determine social status with a level of low nobility competing for the attention of the priesthood.

Tsnarta is similar to Silkutha; the tension between land-owning and animal-rearing Khadya has a heavy influence on local politics.

Kath was once firmly within the cultural sphere of the neighboring Khaji Region, but as the primary site of the Mutul colonial administration, it has been deeply influenced by the Mutul. The clerical public administration, unlike Mata, has lead to the softening of the castes. The Green Stone School, known for adopting Mutul religious practices, is the locus of authority. Families, like in all of Benaajab, accrue social status through their interactions with the priesthood, but in Kath Region, this takes the form of ritual behaviors such as tattooing, flagellation, and sacrifice. Honorifics associated with these rituals are an important part of public life.

Khaji Region, which surrounded the Bay of Khajiphala, is one of the few places where the aristocrats have not been supplanted by the priests or been overshadowed by the economic power of other castes. The administration of the castes is very stringently controlled by the tax-collecting "Bāmana", minor titles granted to cadet branches of the great houses. Immediate family ties are very important in Khaji and, to a lesser extent, ones family history and the number of intermarriages it has had to a higher house.

The Verdant Region, which includes the Sabatian coast, has the strongest representation of the Sangma familial subcaste, which is an endogamous association of related Suta. The Sangma are a distinct ethnicity from the Jati or Jhilam groups and have, since the rule of the Golden Khaganate, been considered unclean as a group for their refusal to adopt the practices of the Zhuz.