History of Hetfold

The Hazedgars have a long, mythic past with origins in the central steppes. They descended into Nordania and, according to their folk histories, were unified under the leadership of the Great Prince Arpazhar. The Hazedgars conquered many of the smaller Norse/Celtic states. They practiced a strict system of de-urbanization in conquered areas, completely destroying any permanent habitations that they found. After making the populace homeless, they would be required to relocate and rebuild their communities, often on the site of another village. The first thing they did on their arrival was to erect stone houses for their Hazedgar overlords before being allowed to build their own homes. This effectively allowed the Hazedgars to transfer the more stable, long lasting properties to themselves while forcing the natives to live in wooden or adobe houses. Over time, the regulations over who was allowed to live in stone homes was greatly relaxed and wealthy citizens of any origin were allowed to purchase the right. The control of durable goods, such as stone housing, became a permanent feature of the Hazedgar conquests.

After suffering several large defeats to coalitions of local states, however, the Hazedgars were forced back north towards their primary mountain powerbase. They were later joined by migrating Turkic peoples are were able to renew their conquests. It was also during this time that the Hazedgar Great Prince Carpazhad converted to Annwynism and allowed the druids to join his courts. This greatly reduced the pressure on the Hazedgar government since some druids endorsed the Hazedgars. The second conquest resulted in the formation of the Kingdom of Hazedgaria, which was a strong, centralized state with its capital at Levitzag. They instituted the Stones Law, which was a corvee system that required those who lived in wooden (or other “temporary”) structures to assist the constant maintenance and repair of the wooden homes and, more importantly, on public projects. This proved to be a very effective system and allowed Hazedgaria to quickly develop a network of granaries, fortifications, and religious sites connected by well-maintained roads. As the complexity of the projects grew, however, the kings of Hazedgaria relied more and more on the local Stone-born population to administer their kingdom. Ultimately, the reliance on local lords, and the steady creation of fortifications in Hazedgaria, resulted in the formal limitation on the monarch’s powers. The constitution of Hazedgaria codified the status of the Stone-born, druidry, and the monarch. The constitutional state was short-lived, however, as Hazedgaria was unable to maintain its statehood without the dominance of the central monarchy.

Infighting began directly after as three forms of state developed: republics, in which all of the stone-born were enfranchised; voivodeships, which rejected and persecuted the druidry; and principalities, which accepted the druidry. During these chaotic times, Arubinian the Radiant rose to power in Mogerden as the captain of the republic there and as a scion of the Alangar Clan. Aurbinian’s successes in wars on behalf of Mogerden not only enlarged that state, but also lead to revolutions all across old Hazedgaria and beyond. The unified state that emerged from this period, the All People’s Alliance of Avérkormánia, enjoyed a great deal of stability and materially contributed to the industrial revolution.

Avérkormánia fell to the Szabolcsist Revolution, which made several important reformations, including universal male suffrage. The wholesale execution of the ruling classes by the Erkölcist faction of the Szabolcsists was a shock the rest of the world. The Szabolcsists later appointed Vazul Prince of the People and he lead a successful conquest of Nordania until an alliance of the other world powers ended Vazul’s reign decisively. The Council of Vatha restored the conquered states of Nordania and instituted a new system of international legitimacy. Hetfold, the post-Avérkormánian state, practiced a form of illiberal democracy with several important factors. The Hetfold government system, which is variably called Septenarianism, Nordpolitika, and Eszakism, has had a strong influence on Nordanian and the world. Important elements include the collectivization of durable assets, the exclusion of women from the primary legislature, and the prominence of family-groups.

Middle Ages

Cities

The typical city of the Hetfold was were the stoneborn / commoners divide was the most apparent. At the center of most cities was the Körrod or “stone palace”, which was both the main dwelling of the city’s prince and the administrative center of the settlement. In the early period, Hazedgar cities followed a strict grid-pattern with separate districts for the stone dwellers and the commoners. These grid patterns can still be seen in some of the Old Towns of modern day Hetfold. But during later periods, notably after the conversion to Annwynism, the social organisation of the cities became less obvious, with stone palaces being built in the middle of “wooden” areas, without a clear cut spatial separation between the two stratas of society.

In the first period of Hazedgar rule, all wooden houses and dwellings belonged to the King and the inhabitants of the cities all paid a rent to the monarch, which served as an early form of taxation. The renting administration of the kingdom became more and more complex because of the always increasing spending of the King’s court, armies, and other state related expenditure. Stoneborns were considered owners of their own palaces and houses and therefore did not have to pay rent or taxes. While at first the right to own a stone house was reserved to the Hazedgars, by the time of the conversion to Annwynism, owning a stone house had become a requirement to access the status of Hazedgar and was a privilege granted either by the King himself or simply by buying a stone property from an Hazedgar. This led in XXXX CE to the creation of a legislation restricting the construction of new stone properties, and limiting the ability of an Hazedgar to own more than one stone house, to avoid business-minded stoneborns to multiply the construction of stone houses only to sell them to wealthy commoners.

The Stone Laws of Hazedgaria allowed for the rapid development of the royal administration, especially related to the handling of the corvées, levies, and rents. But with the fragmentation of these institutions and devolution of power toward local princes, these same princes started to buy and sell lands and properties to both other stoneborns and commoners. Wealthy woodborns individuals became owners of entire “wooden districts” and their densely packed tenements, and collected their rents. Mortgages became common.

A constant constraint of urban life was the alimentation of the population. The original city plans had different kinds of markets and professions well separated from one another, with butchers and tanners in the western districts of the city and near the animal and meat markets. Royal edicts outlawed “dead animals” and raw meat from passing the city’s gate, forcing slaughterhouses to be present directly inside the walls.

The alimentation of a city in cereals was also strictly regimented. It could come in three forms: flour produced by millers from less than three days away from a city could be directly sold in that city’s market. Breads, generally weighing between 2 to 5 kg piece, could come from further away, with no exact limit to the travel time between the baker and the market. And finally, landlords from a city’s countryside sold a large part of their land’s production on the city’s market, generally with fixed pricing depending on previous contracts passed between the city’s authorities and the producer. During the late Hazedgaria period, other methods existed for city dwellers to gain a reliable supply of food, such as being themselves landowners and regularly importing bread from their countryside reserves. During periods of drought or famine, state restrictions on grain prices were lifted and grain could be imported from distant regions of the kingdom, if not from other countries altogether.

During the transition between the Second and Third Principalities, private mills started to appear, built in wood. These mills never developed further in the countryside because of a lack of funds and capital, but the dire need of the growing cities led to the adoption of privately owned mills, on the condition that they were built out of wood. Ship mills became common, financed by a system of joint-stock companies.

Fishing was especially prominent on the northern coast, with salted herrings being the main export to the early internationales markets. This demand for herring throughout the country also led to the development of the salt industry, both from Hazedgars salt mines but also from salt producers worldwide. While fish was an irreplaceable source of protein for the Hazedgars, the fishing profession itself was reviled. The operation of fishing fleets typically fell under foreign companies from around the Tynic. The famous fish markets of Arpalkoez were known for being able to purchase an infinite amount of fish; independent Nordanian fishermen would often spend a season fishing for Hazedgaria before returning home for a season.

Access to clean water was ensured by the strategic location of the cities with rivers passing near or sometimes through the urban area. Water carriers would then sell it to the other inhabitants who did not have the time to draw water themselves. Throughout the middle and late Hazedgaria Period, wells, aqueducts, canals, and so on would be built and maintained through the system of corvées to facilitate the access of the cities to clean water in the face of the growing population. But the main beverage drank by the urban population was not water but beer, either produced at home, locally by brewer-innkeepers, or in the countryside by specialized and famed breweries and then exported to the cities.

Because of the legal limitations of construction materials, common housing had to be built in wood, generally through a timber framing method. Brick was also common in regions with a reliable supply of clay. Bricks were a middle ground for the middle class, as it remained a readily accessible, but expensive, material untouched by the Stone Law. It gave birth to its own distinct architectural trends and fashions, more often mimicking the style of stone houses and buildings but sometimes taking wide departures from it. For example, brick buildings from the middle of the Hazedgaria Period are generally considered to have been built on the Brick Gothic style. In the same period public buildings and infrastructure also started to be built in bricks because of the increasing costs of stone and other “noble” materials, which is generally seen as a herald of the future deliquescence of the Hazedgaria State.

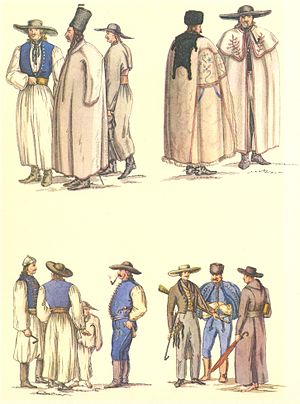

One of the most important industries on which life in many cities depended was the textile industry. Quality wool would be imported from very far away to create the renowned Hazedgar clothes. This industry will ensure the livelihood of many workers, artisans, and traders, and allow for massive private investments and capital. One of the great changes of the late Hazedgaria Period was the technical evolution of the textile industry which allowed for the use of different kinds of wool to produce a light and resilient clothes more in tune with the fashion of its time. This made the local Hazedgars wool producers enjoy a new source of profit, as the cities dependent on the production of the old kind of clothes had to adapt or slowly wither, in parallel to the emergence of new industrial centers. Compensating for the reduction of foreign wool imports, dyes were now in very high demand, as these new clothes could support more dye-baths, allowing for darker colors.

Rural Communities

The Hazedgar village is characterized in a similar fashion to that of the city. During the Carpazhad Period, or Second Principality, the standard Hazedgar village was centered around a stone residence, sort of villa rustica from which the Stoneborn ruler of the settlement supervised the exploitation of the land. Around this building was a collection of wooden residences not following any kind of grid or urban planning. These houses had their own gardens, from which the farmers obtained vegetables, fruits, and meat (mostly in the form of chicken and sometimes pork) and all the companage to go with their bread. The main activity of the farmers was to take care of the seigneurial lands. As such, Hazedgar villages were first and foremost “plantations” in the eyes of the administration, growing mainly cereals like wheat, barley, and rye. Some of these settlements also specialized in raising livestock like sheep, cattle, occasionally even horses, or orchards. Seigneurial lands were exploited following the principles of intensive farming, with the goal to turn a profit by exporting the production to the cities, contrary to the gardens which were entirely dedicated to subsistence agriculture. In the following principality, the rural settlements would keep the same general organization and administration, but new crops would be introduced from the south, such as maize in the well-irrigated provinces.

Very few other buildings beyond the main villa were built in stone in early Hazedgar settlements. The communal mill, forge, and stove, all belonged to the King and were therefore built in stone. They all participated in the collect of taxes in some way: the farmers received half of the seigneurial land’s production as payment. On top of that, the mill kept ten percent of the flour produced and the stove another ten percent of all the bread made for a total tax rate of around sixty percent. But beyond these simple taxes collected by royal inspectors, farmers and villagers were the main source of manpower for the corvées and public works organized by the royal state. Such unpaid work was done with the objective of constructing public infrastructures such as roads, canals, wells, aqueducts, granaries, fortifications, and etc.the village’s forge was especially important in that matter, producing tools and equipment for the local Stoneborn, who would then distribute it to the farmers and workers. The village’s Stoneborn also had the responsibility of organizing the worker groups, serve as a first instance court of justice in case of conflict, and recruit troops in time of war. With time, these Stoneborns became de-facto feudal lords, with titles and charges staying inside the same clan.

Because of its tropical climate, Hetfold has only two seasons: one humid and one dry. In the vast Savannas, the traditional cultivars were either sorghum and different kinds of millet, or barley. In more humid seasons, maize and wheat were also sown. Depending on the kind of cereals produced in a village, the main dish of any meal was either bread or cake, served with broth.