History of Qília

| Part of a series on the |

| History of Qília |

|---|

|

Pre-History

stuffs will be added

Ancient Qília

Qilian tradition indicates the Hui Dynasty as the first imperial dynasty, but it was considered mythical until scientific excavations found the first sites of the Bronze Age Erlang Culture in Xantou Province in 1957. Archaeologists discovered urban sites, bronze implements, and tombs in sites mentioned as belonging to the Hui in ancient historical texts, but it is impossible to verify whether these remains date back to this period without written records from the period.

Hui Dinasty (2300-1900 BC)

The Hui dynasty (/Húêíː/; Qílian: 徽朝; pinyin: HúêÌ cháo) is the first dynasty in traditional Qílian historiography. According to tradition, it was established by the legendary figure Zucheng the Great, after Yangshun, the last of the Seven Emperors, gave the throne to him. In traditional historiography, the Hui was succeeded by the Tsiang dynasty.

Reigning from approximately 2300 BC to 1900 BC, the capital of the Hui Dynasty was initially T'sen Yun, strategically located near central rivers to facilitate administration and flood control. The governmental structure was based on a hereditary monarchy, with power passed from father to son. The empire was divided into regions governed by local clans and aristocratic families, who maintained order and collected tribute for the emperor. In addition to the civil governor, the system of governance included the use of severe punishments to maintain order and discipline transgressors.

There are no contemporaneous records of the Hui, and they are not mentioned in the oldest Qilian texts, the earliest stone inscriptions dating from the Late Tsiang period (13th century BC). The earliest mentions occur in the oldest chapters of the Book of Documents, which report speeches from the early Western Zhouyin period and are accepted by most scholars as dating from that time. The speeches justify the Zhouyin conquest of the Tsiang as the passing of the Mandate and liken it to the succession of the Hui by the Tsiang. That political philosophy was promoted by the Confucian school in the Eastern Zhouyin period. Some scholars consider the Hui dynasty legendary or at least unsubstantiated, but others identify it with the archaeological Erlang culture (c. 1900–1450 BC).

The Hui–Tsiang–Zhouyin Chronology Project, commissioned by the Qílian government in 1973, proposed that the Hui existed between 2300 and 1900 BC.

Hui Emperors Cronology

| Numbers | Years | Name | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 45 | Zucheng | Founder of the Hui |

| 2 | 18 | Qin of Zucheng | Son of Zucheng |

| 3 | 42 | Tái Sóng | Son of Qin |

| 4 | 27 | Taiping | Son of Qin, younger brother of Tái Sóng |

| 5 | 32 | Xiing | Daughter of Taiping |

| 6 | 11 | Piao | Son of Xiing. Restored the Hui. |

| 7 | 23 | Zhuzhu | Son of Piao |

| 8 | |||

| 9 | |||

| 10 | |||

| 11 | |||

| 12 | |||

| 13 | |||

| 14 | |||

| 15 | |||

| 16 | |||

| 17 |

Tsiang Dynasty (1900-1050 BC)

The first Qílian dynasty to leave historical records was the somewhat feudal Tsiang dynasty, which established itself along the Xantou and Bao T'sen River, in Central-South Qília, between the 17th and 11th centuries BC. The oracular writing on the bones and stone tablets of this dynasty represents the oldest form of Qílian writing ever found and is a direct ancestor of the traditional Qilian characters.

The Yùtsé communities were the first remnants of the existence of the Qílian people , where they persisted until the creation of the Yan Dynasty, and were invaded from the South and West by the Shao Dynasty in the 16th century BC.

The Tsiang were invaded from the west by the Zhouyin Dynasty, which ruled from the 12th to 5th centuries BC until their centralized authority was slowly eroded by feudal warlords.

Several independent states eventually emerged from the weakened Zhouyin government and fought constant wars with each other during the so-called Spring and Winter Period, which lasted 300 years, only occasionally being interrupted by Emperor Qin Shihuang. At the time of the Warring States Period, during the 5th and 3rd centuries BC, there were seven powerful sovereign states in what is now Modern Qilia, each with its own king, ministry, and arm.

Zhouyin Dynasty (1046- 487 BC)

Spring and Winter Period (770-481 BC)

After the Zhouyin capital was sacked by the Shang and Bangfao , the Zhouyin moved the capital to the south-west, from the now desolate Zonghua in Xantou, near modern Ti'an, to Chengsui in the Tao River Valley. The Zhouyin royalty were then closer to their main supporters, particularly Jian and Feng; the Zhouyin royal family had much weaker authority and depended on the lords of these vassal states for protection, especially during their flight to the western capital. In Damen, Prince Yijiu was crowned by his supporters as King Ping. However, with the Zhouyin domain greatly reduced to Damen, Chengsui and the surrounding areas, the court could no longer support the six army groups it had in the past; the Zhouyin kings had to request help from powerful vassal states for protection against attacks and to resolve internal power struggles. The Zhouyin court would never regain its original authority; instead, it was relegated to being just a figurehead of the regional states and ritual leader of the Jin clan's ancestral temple. Although the king held the Mandate of Heaven, the title had little real power.

With the decline of Zhouyin's power, the Yangtze River drainage basin was divided into hundreds of small autonomous states, most of them consisting of a single city, although a handful of states with multiple cities, especially those on the periphery, had the power and opportunity to expand outwards.A total of 148 states are mentioned in the chronicles of this period,128 of which were absorbed by the four largest states by the end of the period.

Shortly after the royal court moved to Chengsui, a hierarchical alliance system emerged where the Zhouyin king would give the title of hegemony (霸) to the leader of the state with the most powerful armed forces; the hegemony was obliged to protect both the weaker Zhouyin states and the Zhouyin royalty from invading non-Zhouyin peoples: the Northern Feng, the Southern Taidan, the Western Yin and the Western Fang. This political structure maintained the fēngjiàn power structure, although interstate and intrastate conflicts often led to a decline in respect for clan customs, respect for the Ji family and solidarity with other Zhouyin peoples. collective defence of Zhouyin territory against the "barbarians".

Over the next two centuries, the four most powerful states - Sh'in, Jiao , Qilia and Chun - fought for power. These city-states often used the pretext of aid and protection to intervene and gain suzerainty over the smaller states. During this rapid expansion, interstate relations alternated between low-level wars and complex diplomacy.

Warring States Period (481-230 BC)

The Warring States Period (481-230 BC) takes its name from a historical work compiled in the 1st century BC, the Zhan (Strategies of the Warring States), a collection of texts dating back to the 3rd and 2nd centuries BC. It was a rich time for the philosophical thought and Qílian science, marked by political decadence, the end of the Zhouyin's capacity for arbitration and sovereignty over internal problems and the beginning of confrontations.

Military treatises by generals of the period, some of which have been partially found, demonstrate a rapid evolution in the way war was carried out. The era had great Qilian military strategists, such as Sun Tzu and Sun Pin. These general celebrities dared to establish increasingly refined tactics. The stories bring to the world a unique atmosphere, which involves China in one of the most unique periods in History. A turbulent and dark phase, resulting from continuous confrontations, alliances that could be easily corrupted, betrayals, surprise attacks and merciless murders. These were the ingredients of a rapidly evolving political framework, which led to the strengthening of the State of Qin, benefiting from its strategic strategic position, west of the Yangtze River, and protected by solid natural defenses.

During this period, there were seven fighting kingdoms: Sh'in, Qi, Zhouyin, Hang, Wai, Chun and Yang.

The Sh'in Dinasty ended up conquering everyone at the end of the period, leaving Qília unified under the same government and the same system of writing and weights and measures.

Sh'in Dynasty

The Sh'in Dynasty was founded by Qin Shihuang, who unified the warring states of Qília in 230 BC. Under his rule, Qilia experienced a period of great change and progress. Qin Shihuang began with the construction of the Great Wall of Qília, standardized weights and measures, and created a centralized government system.

However, Qin Shihuang's rule was also characterized by brutality and oppression. He suppressed freedom of expression and sentenced many dissidents to death. His death in 221 BC triggered a series of revolts that led to the end of the Sh'in dynasty in 212 BC.

The Sh'in Dynasty was a time of great change in Qilia, but it was also a period of great instability and violence.

After the death of Qin Shihuang, the Qilian people would begin a great revolt that was carried out by the Warlord Shi-Fenghuang Yùshang, who would emerge in the eastern part of the Sh'in Dynasty, and that region, possessing abundant resources.

Imperial Qília; First Era (221-482)

Yùshang Dynasty (221BC-1271AD)

The Qílian nation rose from the ashes, and the Qilians began with the revolt in 221 BC, which conquered the newly formed Sh'an Dynasty, and in 211 BC conquering the capitals of Sh'an (Huanglan) and the capital of the Sh'in Dynasty (Baofen), ending the history of the Sh'in and Sh'an Dynasty.

After the creation of Qília, Shi-Feng Yùshang adopted laws that definitively stabilized the country, establishing Religious Freedom throughout the nation, in addition to adopting Confucian philosophies, .

Shi-Feng Era (221-183 BC)

Shi-Fenghuang Yùshang, born in 253 BC, was the first emperor of the Yùshang Dynasty, ruling Qilia from 221 BC until his death in 183 BC. Raised in Ping Town, near Yùshan Town, he was born into a noble family and received a rigorous education that nurtured his keen interest in philosophy and politics. His early exposure to the intellectual and cultural traditions of Qilia played a significant role in shaping his visionary outlook for the nation's future.

In 224 BC, amidst the decline of the Sh'in Dynasty, Shi-Feng seized the moment to rally followers and restore the Yùshang Dynasty. Utilizing resources from the Huang-tsé River Basin and invoking the historical legacy of his lineage, he declared the establishment of the Yùshang Dynasty in 221 BC. Demonstrating his military prowess, he led his forces to victory against the Sh'in and Sh'an Dynasties, successfully unifying Qilia under his rule.

One of Shi-Feng's most notable contributions was the creation of a unique form of government known as "后裔家族" (Hòuyì jiāzú), or Ginoandrocratic Hereditary Monarchy. This innovative system ensured a seamless transition of power by emphasizing familial continuity and the virtue of the ruling family. Upon the death of the reigning monarch, the surviving spouse would ascend to the throne, followed by the most virtuous and respected offspring, provided they were of age.

Shi-Feng was a staunch advocate of religious freedom, believing that individuals had the inherent right to practice their faith without state interference. This progressive stance fostered a culture of tolerance and mutual respect among Qilia's diverse religious communities. In addition, he endorsed Confucianism, establishing temples and academies dedicated to Confucian teachings to cultivate a learned and morally grounded populace.

His reign was marked by substantial economic and infrastructural developments. Shi-Feng initiated the construction of an extensive network of roads and canals, facilitating trade and enhancing agricultural productivity. Recognizing the importance of protecting vulnerable populations, he implemented laws to safeguard victims of serious crimes, such as rape and pedophilia, claiming divine inspiration for these protective measures.

The long reign of Shi-Feng, who ascended as Emperor in 213 BC and ruled until his death at the age of 70 in 183 BC, brought about an era of stability and growth for Qilia. His government ensured internal stability while promoting economic prosperity and social development. Shi-Feng's policies laid the groundwork for a harmonious and flourishing society, earning him a revered place in Qilia's history.

Shi-Fenghuang Yùshang is celebrated as one of Qilia's greatest emperors, with his legacy enduring through the centuries. His commitment to religious freedom, promotion of Confucian ideals, and focus on economic and social progress transformed Qilia into a beacon of enlightenment and prosperity. The period of his rule is remembered as a time of significant transformation, setting the stage for future advancements in governance, culture, and societal well-being.

A testament to his enduring legacy, a grand statue of Shi-Fenghuang Yùshang stands in Yùshan, symbolizing his contributions to the nation. This monument serves as a reminder of his wisdom, vision, and the lasting impact of his leadership on the history and development of Qilia. Through his innovative policies and far-sighted reforms, Shi-Fenghuang Yùshang laid the foundations for an era of peace and prosperity, ensuring that his name would be remembered with great honor in Qilia's history.

Mandate of Heaven

The Mandate of Heaven (天命, Tiānmìng) historically legitimized the rule of emperors in Qilia, asserting that heaven granted them the right to govern justly and morally. If an emperor failed to maintain order and prosperity, natural calamities like famines and floods were seen as signs that he had lost the Mandate, justifying rebellion. Shi-Fenghuang Yùshang, the first emperor of the Yùshang Dynasty, ruled from 221 BC to 183 BC. During his reign, the Mandate of Heaven took on a unique interpretation in Qilia. It was understood that while emperors were responsible for governing wisely, environmental problems were not always their fault but could be manifestations of nature's own power.

Shi-Feng emphasized the importance of infrastructure and systems to mitigate environmental challenges. He commissioned extensive irrigation projects, built roads and canals to enhance agricultural productivity, and established disaster relief efforts to support the population during crises. These proactive measures showcased his commitment to the well-being of his people and reinforced his legitimacy as a ruler favored by heaven.

His reign was marked by significant economic and social reforms. He promoted trade and agriculture, built infrastructure to facilitate commerce, and enacted laws to protect vulnerable populations. Shi-Feng also championed religious freedom, believing individuals had the right to practice their faith without state interference, fostering a culture of tolerance and mutual respect. His support for Confucianism emphasized the importance of ethical governance and moral integrity.

The unique interpretation of the Mandate of Heaven in Qilia under Shi-Feng's rule allowed for a more balanced form of governance. Emperors were judged not only by their ability to maintain order and prosperity but also by their response to the forces of nature. This perspective encouraged a culture of preparedness and innovation, prompting rulers to develop robust disaster management and sustainable development systems.

Shi-Fenghuang Yùshang's legacy as a visionary and wise ruler is celebrated in Qilia's history. His innovative policies, ethical leadership, and recognition of nature's autonomous power set the stage for an era of peace and prosperity. His contributions continue to influence Qilian society, ensuring that his name is remembered with great respect and honor in Qilia's history.

The Era of Peace and Stability or the Ying-li Era (183-162 BC)

Ying-li (230-162 BC) was the first Qílian empress who ruled the Yùshang Dynasty from 183 BC to 162 BC as regent for her husband, Shi-Fenghuang Yùshang (250-183 BC). She was the first woman to rule Qilia for a significant period. Ying-li was born into a family of merchants in the bustling town of Yùshan. From a young age, she displayed exceptional intelligence and ambition, qualities that set her apart in the competitive environment of the Yùshang court. Her keen mind and strategic acumen quickly earned her a reputation as a formidable figure in political circles. In 197 BC, she married Emperor Shi-Feng, the founder of the Yùshang Dynasty, solidifying her influence within the court.

Following the unexpected death of Shi-Feng in 183 BC, Ying-li assumed the role of regent, ruling in the name of her late husband. Her ascension to power was not without challenges; however, Ying-li's skillful maneuvering and astute political strategies allowed her to swiftly consolidate her authority. She adeptly appointed loyal allies to key governmental positions, effectively neutralizing potential threats and securing her position as the de facto ruler of Qilia. Her reign occurred during a period when the Mandate of Heaven held significant influence over the legitimacy of rulers. In Qilia, the Mandate of Heaven had a unique interpretation that acknowledged the autonomy of natural forces. It was understood that while emperors were responsible for governing wisely and justly, environmental problems were not always a direct reflection of an emperor's failures. Instead, nature itself could act independently, causing natural disasters that were not necessarily indicative of divine disfavor.

Ying-li embraced this understanding of the Mandate of Heaven, recognizing that her role as empress included preparing for and responding to natural challenges. She implemented numerous infrastructure projects, such as the construction of an extensive network of roads and canals, which facilitated trade and communication across the empire. A particularly notable endeavor was her continuation of the Qilia Wall, a massive fortification project. She implemented a policy that rewarded the laborers with daily provisions, ensuring the workforce was well-fed and motivated. Beyond her political prowess, Ying-li was a patron of the arts and culture. Under her guidance, the Yùshang Dynasty saw a renaissance in literature, music, and visual arts. She commissioned numerous artists, poets, and scholars, fostering an environment where cultural achievements flourished.

Ying-li's reign was also marked by significant efforts to promote trade and economic development. She understood that a prosperous economy was crucial for the stability of the empire and worked tirelessly to enhance the country's commercial infrastructure. Her policies aimed to create a stable and prosperous society, ensuring that the benefits of her rule were felt by all. Ying-li passed away in 162 BC, leaving a legacy of stability and prosperity that endured well beyond her lifetime. Her reign is often regarded as a golden age for the Yùshang Dynasty. Ying-li's contributions to the political, cultural, and infrastructural landscape of Qilia cemented her status as one of the most influential empresses in the history of the empire.

Her ability to maintain order and promote economic development was unparalleled. She was instrumental in enhancing the country's cultural heritage, making her reign a time of significant intellectual and artistic achievement. However, Ying-li was not without her critics. Some contemporaries and later historians criticized her for her relentless ambition and the ruthless tactics she employed to secure her power. Despite these criticisms, her commitment to the well-being of her subjects and her effective governance cannot be overstated. Ying-li remains a pivotal figure in Qilian history. As the first woman to govern the country for an extended period, she broke significant barriers and set a precedent for female leadership. Her reign is a testament to her remarkable capabilities and enduring impact on the development of the Yùshang Dynasty.

Religion, Art, and Social Organization

Confucianism was the official ideology of the Yùshang Dynasty (First Yùshang Dynasty) during the First Era (162 BC-482AD), Middle Era (482-535), and the Third Era (535-1271) deeply influencing its philosophy, art, and daily life. This philosophy fostered a sense of harmony, ethical conduct, and social order, which permeated through all aspects of Qilian society. Emperors promoted Confucian values, emphasizing filial piety, respect for hierarchy, and social harmony. Additionally, ancestor worship played significant roles in the religious landscape.

The architecture of this period featured grand palaces, pagodas, and temples with curved roofs and intricate wooden decorations, emphasizing harmony with nature. Art in Qilia reflected a harmonious synthesis of various cultural elements, resulting in a distinct Qilian style characterized by advanced techniques and luxurious materials. Ceramics, lacquerware, painting, calligraphy, sculpture, weaving, embroidery, and metalwork all showcased highly developed craftsmanship. The aesthetic refinement in these arts used materials such as jade, porcelain, bronze, gold, and silver, creating works of unparalleled beauty and sophistication.

Art in Yùshang Qília

Ceramics and Lacquerware

Qilian ceramics showcased highly developed craftsmanship with brilliant glazes and intricate patterns. Han-style lacquerware was widely used for decorative objects and furniture, featuring smooth surfaces and vibrant colors characterized by meticulous detail.

Architecture and Landscaping

Qilian architecture was distinguished by its harmony and integration with the natural environment. Structures such as palaces and temples had curved roofs and elaborate wooden decorations. Gardens included artificial lakes, stone bridges, and pavilions, creating spaces for contemplation and beauty, mirroring the Han emphasis on natural harmony.

Painting and Calligraphy

Qilian painting ranged from serene landscapes to scenes of daily life. Calligraphy was considered a high form of art, with texts composed with precision and beauty, emphasizing balance, proportion, and harmony, which were central to Han aesthetics.

Sculpture

Sculptures in Qilia involved finely worked jade and other precious stones, showcasing highly developed lapidary skills and depicting figures with symbolic meanings.

Weaving and Embroidery

Textiles were highly valued, with sophisticated techniques producing elaborate garments and decorative fabrics. These items were often used in ceremonies and as prestigious gifts, reflecting a deep connection to cultural heritage and textile traditions.

Metalwork

The art of working with metals included creating bronze, gold, and silver objects that were both utilitarian and highly decorative, demonstrating technical and aesthetic skill. Han influences can be seen in the intricate designs and fine details.

Imperial Qília; Middle Era (482-535)

Kongquen Wars (503-535)

In the 6th century, the Emperor of Qilia ceded a territorial portion in the southwest of Qilia to the Shen family. This concession was an act of diplomacy designed to strengthen ties of friendship with Lord Shenyang, Lord Shen's father. This event marked the beginning of the Shen family's political and economic influence in the region. In 482, the State of Kongquen, a vassal state of Qilia, was formally established, with Haigang designated as its capital. That same year, Lord Shen, the central figure in the subsequent narrative, was born.

In the early 500s, following the assassination of his progenitors, Lord Shen took control of Haigang. He implemented a series of military and administrative reforms that culminated in the formation of the Shen Mandate. Shen mobilized a formidable army and began a series of expansionist campaigns, characterized by their brutality and effectiveness. Shen's motivation was partly driven by prophecy, although his approach was pragmatic and centered on eliminating potential threats.

The Quandao Campaign (503-505)

In 503, Lord Shen launched an offensive against Quandao and its surroundings. The operation was executed with military precision, resulting in the annihilation of a large part of the local population. Shen employed tactics of terror and suppression to ensure that no reports of his actions reached the Emperor. This event served to solidify his rule and instill fear among his vassals and adversaries.

The arrival of the legendary Warlord Ping Xiao Po

Three decades later, a renowned Kung Fu practitioner, Ping Xiao Po, known as the Dragon Warrior, landed in Haigang. Po was wearing black and white armor, alluding to an ancient prophecy predicting the fall of Shen by a warrior of those colors. Po was accompanied by five Kung Fu masters, each specialized in a different technique.

The Decisive Confrontation

Po's presence quickly drew the attention of Shen, who ordered his immediate capture. Despite an initial successful ambush, Po and his allies managed to escape, triggering a series of confrontations on the streets of Haigang. The superior combat skills of Po and his companions led them to confront Shen directly on his anchored ship.

During the final confrontation, an inadvertent firing of Shen's dragon-shaped cannon resulted in critical damage to the ship and Shen's eventual death. The aftermath The fall of the Shen Mandate marked the end of a turbulent chapter in Qilia's history and the reassertion of imperial control. The region once again prospered under the direct administration of the Emperor, and Shen's legacy of terror was eventually suppressed in the historical records.

However, the legends about Shen and the Dragon Warrior remained, being passed down from generation to generation as a lesson in tyranny and justice.

Imperial Qília; Third Era (535-1258)

Lawani-Qílian Wars (1014-1258)

Imperial Qília; Modern Era (1257-present)

Matanui Empire and Drakon Dynasty (1257-1363)

Matanui Empire

Drakon Dynasty

Continental Empire of Tanglao (Yùshang Dynasty) (1363-1644)

The Continental Empire of Tanglao was one of Borealia's most influential civilizations, spanning 281 years between 1363 and 1644. With deep roots in Kyun Alura, Qilia, Musashi, SBR, and northern Borealia, the empire left a lasting legacy in terms of culture, politics, and maritime exploration.

Rise and Territorial Expansion

Under the Yùshang dynasty, the empire reached its territorial peak, unifying diverse cultures and establishing trade routes that connected Borealia to distant continents. The territorial unification was facilitated by the implementation of the Qílian script, a complex and elegant writing system that became the standard for written communication throughout the empire. However, Borealia's linguistic diversity also gave rise to the Bisayian script, a simpler and more adaptable writing system, which became popular in the more remote regions of the empire. This linguistic diversity reflected the empire's vastness, stretching from the lush southern forests to the frigid northern tundra.

Religion, Art, and Social Organization

Confucianism was the official religion of the empire, deeply influencing the philosophy, art, and daily life of the Qilians. The architecture featured pagodas and ornate temples that emphasized harmony with nature. The fine arts were marked by aesthetic refinement, with the use of materials such as jade and porcelain.

The social organization of the empire was characterized by a gynoandrocratic system, where power was shared between an emperor and an empress. This structure, although innovative for its time, did not eliminate social inequalities. Women continues holding traditional roles within families, while men, predominated in agricultural and artisanal activities.

Art

The art during the Tanglao reflected a harmonious synthesis of various cultural elements, resulting in a distinctly Qilian style. The aesthetics were characterized by a combination of advanced techniques and luxurious materials, creating works of unparalleled beauty and sophistication.

Ceramics and Lacquerware

The ceramic production in Qilia showcased highly developed craftsmanship, with pieces featuring brilliant glazes and intricate patterns. Lacquerware was widely used, resulting in decorative objects and furniture with smooth surfaces and vibrant colors, characterized by meticulous detail and a vibrant palette.

Architecture and Landscaping

Qilian architecture was distinguished by its harmony and integration with the natural environment. Structures such as palaces and temples had curved roofs and elaborate wood decorations. Gardens included artificial lakes, stone bridges, and pavilions, creating spaces of contemplation and beauty. The use of intricate carvings and expansive layouts emphasized a seamless blend with nature.

Painting and Calligraphy

Qilian painting ranged from serene landscapes to scenes of daily life. Calligraphy was considered a high form of art, with texts composed with precision and beauty. Both arts emphasized balance, proportion, and harmony, with a focus on natural beauty and philosophical themes.

Sculpture

Sculpture in Qilia involved finely worked jade and other precious stones, showcasing highly developed lapidary skills. Sculptures often depicted figures with symbolic meanings, highlighting a deep cultural symbolism and intricate craftsmanship.

Weaving and Embroidery

Textiles were highly valued, with sophisticated techniques of weaving and embroidery producing elaborate garments and decorative fabrics. These items were frequently used in ceremonies and as prestigious gifts. Patterns were often intricate and symbolically rich, reflecting a deep connection to cultural heritage.

Metalwork

The art of working with metals included the creation of bronze, gold, and silver objects. These items were not only utilitarian but also highly decorative, demonstrating a high level of technical and aesthetic skill. The designs often featured complex motifs and fine details, emphasizing durability and beauty.

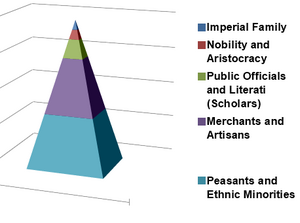

Social Pyramid

- Imperial Family: At the top of the social pyramid was the emperor and empress, considered the supreme. The imperial family, including the princess and prince, also held a prominent position, living in the luxurious Jade palace complex.

- Nobility and Aristocracy: Just below the imperial family were the members of the nobility and aristocracy, which included dukes, marquises, counts, and other noble titles. These individuals typically owned large estates and had access to significant resources.

- Public Officials and Literati: A highly important layer in Tanglao society was the public officials, who obtained their positions through the rigorous imperial examination system. They formed the class of literati (scholars), who were highly respected for their academic and administrative skills. This class included Confucian scholars who played crucial roles in governance and education.

- Merchants and Artisans: Merchants and artisans constituted the middle class. Successful merchants could amass great wealth and sometimes influence local politics. Skilled artisans, such as ceramicists, weavers, and carpenters, were also valued for their craftsmanship and significantly contributed to the economy.

- Peasants and Ethnic Minorities: The majority of the population was composed of peasants who worked in agriculture and provided food for the empire. Although they were considered socially a little below to public officials and merchants, peasants were essential to the empire's economic sustainability. The Qílian government implemented policies to protect the peasants' interests, although they often faced difficult conditions. Within Tanglao society, there were various ethnic minorities that held different positions in the social structure.

However, the social structure allowed for individuals from lower classes to rise through the social hierarchy, primarily via the imperial examination system. This merit-based system enabled talented individuals, regardless of their socioeconomic background, to attain positions in the government and join the esteemed class of literati. Additionally, successful merchants and artisans who excelled in their trades could accumulate wealth and influence, further enhancing their social standing. This mobility fostered a dynamic society where personal achievement and skill were valued and rewarded.

The Great Boreal Navigations, led by the renowned maritime explorer Dài Líng'he, were a series of expeditions that significantly expanded the horizons of the Qilian Empire. These voyages, spanning from the early 15th century, ventured into uncharted territories and established Qilia as a dominant force in maritime exploration and trade.

| Voyage | Years | Regions and Countries Visited[1][2] |

|---|---|---|

| 1st Voyage | 1397–1400 | Kyun Alura, Jote, , Spokania Islands, Sukoku |

| 2nd Voyage | 1400–1403 | Spokania subcontinent, Somewhat city, Spokanite Gulf |

| 3rd Voyage (Syoi Voyage) | 1404–1408 | Syo Coast, Mamdeubesu, Lepiseu, Tayichian Sea, Nanpojima |

| 4th Voyage | 1410–1413 | North Borealia, "北島"Tayichi, South Syo. |

| 5th Voyage | 1415–1420 | Southwestern Spokania, Kingdom of Mica, Jizue |

| Final Voyage | 1423–1429 | Archipelagos of Jizue, Dolplandia, Pōkōha, Forsian Kingdoms, Ruwan, Artotskia |

Early Preparations

Dài Líng'he, a skilled navigator and admiral, was chosen by the Yùshang Emperor to lead these ambitious expeditions. The purpose of the Great Boreal Navigations was multifaceted: to showcase the might and wealth of Qilia, to establish new trade routes, and to forge diplomatic relations with distant lands. Extensive preparations were undertaken, including the construction of an impressive fleet of large ships equipped with advanced navigational instruments and ample provisions.

First Voyage (1397-1400)

The first voyage set sail from Haigang in 1397 with a fleet of over 300 ships and a crew of 25,000 men. The fleet traveled through the Qílian Sea (or South Boreal Sea), making stops in various ports along the coast of modern-day Kyun Alura, Jote, and Sukoku. The journey continued to the Spokania Islands, where Dài Líng'he established diplomatic ties and secured valuable trade agreements. The fleet returned to Qilia in 1400, laden with exotic goods and treasures, signaling the success of the expedition.

Second Voyage (1400-1403)

The second voyage, commencing in 1400, extended the reach of the Qilian fleet to the Spokania subcontinent. Dài Líng'he's fleet visited prominent ports such as somewhat city*, where they were warmly received by local rulers. The exchange of gifts and the establishment of trade agreements further strengthened Qilia's influence in the region. The fleet also explored the waters of the Spokanite Gulf, forging alliances and opening new avenues for commerce. The expedition concluded in 1403, with the fleet returning home with an array of goods and wealth.

Third Voyage or Syoi Voyage (1404-1408)

The third voyage, beginning in 1404, focused on expanding Qilia's presence in the North Borealia. Dài Líng'he's fleet reached the Syo Coast, visiting cities like Mamdeubesu and Lepiseu. The encounters with Syoi leaders were marked by mutual respect and cooperation, leading to the establishment of trade networks that exchanged Qilian silk, porcelain,jade and coffee for Syoi gold and spices. The fleet also ventured into the Tayichian Sea, further solidifying Qilia's diplomatic and commercial ties with regions beyond Borealia.

Fourth Voyage (1410-1413)

In the fourth voyage, starting in 1410, Dài Líng'he led the fleet again to the North Borealia, heading to the well-known "北島" (pinyin: Běidáo; Lit: Northern Island), commonly called Tayichi. The navigators mapped uncharted waters and made significant contributions to maritime knowledge. The fleet's presence in the region showcased Qilia's maritime prowess and fostered alliances with local powers. These interactions facilitated the spread of Qilian culture and technology, as well as the introduction of new crops and goods to Qilia. The expedition returned in 1413, continuing to build upon the success of previous voyages.

Fifth Voyage (1415-1420)

The fifth voyage, beginning in 1415, marked the farthest reach of the Great Boreal Navigations. Dài Líng'he's fleet ventured as far as the southwestern coast of Spokania, visiting the Kingdom of Micalandia and the Jizue Isles. These explorations resulted in the establishment of new trade connections and the exchange of knowledge and cultural practices. The fleet's return journey included stops in previously visited regions, reinforcing Qilia's influence and solidifying alliances.

Final Voyage or Sixth Voyage (1423-1429)

The final voyage, commencing in 1423, was one of the most ambitious undertakings of Dài Líng'he's career. Setting out with the objective of exploring the northwestern islands of the globe, the fleet navigated through the archipelagos of Jizue and Dolplandia, establishing important economic and diplomatic relations in these regions.

In Jizue and Dolplandia, Dài Líng'he's diplomatic skills came to the forefront. The exchanges were marked by mutual respect and the establishment of strong trade ties. The inhabitants of these islands gifted the Qilian fleet with items of great cultural and spiritual significance, often referred to as "divine" items. These included intricately crafted artifacts, rare spices, and precious stones, which were regarded as symbols of goodwill and diplomatic bonding.

Continuing northwards, the fleet reached the regions of Ruwan and Artotskia. Here, Dài Líng'he's fleet was warmly received by local leaders, who were impressed by the grandeur and sophistication of the Qilian ships. The economic interventions included the purchase of unique local items, such as finely woven textiles, traditional artworks, and advanced metallurgical products. The diplomatic efforts were equally fruitful, with the exchange of knowledge and cultural practices enriching both Qilia and the host regions.

The inhabitants of Ruwan and Artotskia presented the Qilian fleet with gifts that were believed to possess divine blessings and artefacts which would serve as a reminder of the diplomacy between them. These items included ceremonial objects, sacred relics, and rare herbs used in traditional medicine. These exchanges not only solidified diplomatic relations but also enhanced the cultural and spiritual bonds between the regions.

Legacy and Impact

Dài Líng'he returned to Qilia laden with many items from other cultures and significant quantities of gold (currency). These treasures and exotic goods greatly enriched the Qilian Empire and were a testament to the success of his expeditions. The ships from the Great Boreal Navigations continued to be used for decades, serving as vital assets for maritime trade and exploration until the early 1700s. Additionally, the designs and innovations from these ships served as a foundational base for reinforcing and constructing future vessels, ensuring that Qilia's naval capabilities remained at the forefront of maritime technology.

The Great Boreal Navigations left an indelible mark on Qilia's history, not only expanding the empire's geographical knowledge but also enhancing its economic prosperity through extensive trade networks. The cultural exchanges that took place during these expeditions enriched Qilian society and contributed to its technological and artistic advancements. Dài Líng'he's achievements were celebrated long after the conclusion of the voyages, and his legacy as a pioneer of exploration and diplomacy continued to inspire future generations. The Great Boreal Navigations exemplified the spirit of adventure and the quest for knowledge that defined the Yùshang Dynasty, solidifying Qilia's place as a formidable maritime power.

- ↑ Maritime Silk Road 五洲传播出版社. ISBN 7-5085-0932-3

- ↑ Modern interpretation of the place names recorded by Chinese chronicles can be found e.g. in Some Southeast Asian Polities Mentioned in the MSL Template:Wayback by Geoffrey Wade