Mundaqar

Federation of Mundaqar Udo nke Ugwu Nsọ (Igbo) Salama na Dutsen Tsattsarka (Hausa) | |

|---|---|

| Motto: ′′Faithful and Peaceful′′ | |

| Anthem: Yon Mountain Peaks | |

| Largest city | Alqat |

| Official languages | Wenarei |

| Recognised national languages | Hausa, Igbo, Arabic, Oubastine |

| Government | Federal semi-presidential republic |

• Chairman | Tariq Ximenes |

• Archduke of Duero | Esmeraldo Namib |

• Premier of Braqara | Garcia Munmara |

• Secretary-General | Philip de Virreina |

| Legislature | Confederal Committee |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 177,023,672 |

| GDP (PPP) | estimate |

• Per capita | 16,983 |

| GDP (nominal) | estimate |

• Per capita | 15,543 |

| HDI (2015) | 0.865 very high |

| Currency | Dinar |

The Federation of Mundaqar is a highly devolved federal republic. The Federation is composed of two nations--the Archduchy of Duero de Aqar and the National Republic of Braqara and ten provinces collectively known as Las Faldillas. The capital of Alqat is located in Braqara, but is immediately adjacent to the other two major constituents of the Federation. The modern state was initially formed as a result of the 1886 armistice which created a confederate commission that ruled with the consent of the Sahb-majority populace and the pontificate. During the 1960s, however, the confederate system was overhauled to the modern federate one with a more secular government instead of a multi-polar one.

A number of ancient kingdoms and societies existed in pre-modern Mundaqar.

History

The history of Mundaqar is dominated by a handful of great urban centers called "Obodo nke Mba" or "Cities of the Country," which are large, fortified urban centers at high elevation. There are many of these cities spread out across the various cultural and linguistic groups of of modern Mundaqar, but the highest concentration of these cities occurs on the Nimala strip, between the dry grasslands and the rain forest regions. The oldest of these cities is the Memriniile, which is directly south of modern Alqat, and was built in the third century BCE. A great city typically consisted of a central walled village center containing a palace, a temple, some essential craftsmen, and the agricultural workers in the immediate area. Outside of the central settlement would be a proportional area of around 300 square kilometers, pocked with smaller settlements which would have their own vectors of agricultural land. Around large clusters of settlements was an earthworks fortification, the largest of which enclosed over 16 thousand square kilometers and reached populations of 160 thousand people in the pre-rice period. The great danger during this time came from the interstices of the great cities where there were hundreds of thousands of individuals trapped outside of the protective walls. Warlords rose and fell here, sometimes with the direct support of the Obodo nke Mba, but more often simply to fill the power vacuum. Sometimes these warlords formed their own settlements, but equally often they would built up a great force and take over an existing Obodo nke Mba.

While rice had been farmed in Mundaqar for many years prior, the adoption of domestic rice in the Obodo nke Mba sparked a massive population boom that quickly redefined the political environment. Prior to the introduction of rice, Obodo nke Mba would grow slowly, building out their walls until they became too vast to maintain. The vast walled state would collapse and eventually re-coalesce around another village and the growth cycle would begin anew. With rice, however, the populations of the cities accumulated faster than walls could expand. These much denser settlements triggered a cultural and architectural revolution called the Ịkwado. Within the great cities, Ịkwado meant the construction of larger, taller housing complexes and the decentralization of skilled labor away from the "capital" settlements. Uzoma, one of the great philosophers of the period wrote "The Ịkwado is essentially the crowning of every village with a gem, that gem is the special purpose within the great community of the city". Many villages inherited essential skilled roles such as containing a mill, a butcher, a temple, or some other essential service because the central settlement could no longer serve the entire population. While the population of the Obodo nke Mba exploded, the outer-urban sections of Mundaqar could seldom form coherent enough irrigation systems to take advantage of the crop revolution. Notable exceptions are the river cities, which were called Enweghị Mgbidi or "unwalled" and the expansion of mining settlements which imported food from the cities called Miriulo, the deep homes, both of which developed their own Ịkwado cultures.

Yen Period

During the mid-10th century, all of Mundaqar north of Cazador came under the control of an empire. The great cities were converted, destroyed, or a mix of both. Several cities were allies of the new empire--notably Almenar, Almanza, and Djire--became seats of Governors and enjoyed an influx of foreign culture and trade from across the empire. Other cities such as Kodi and Niry were almost completely destroyed. One of the principle driving forces of the empire was the liberation of slaves, which quickly provided their forces with a ready supply of willing converts wherever they went. The lack of slaves changed the political geography of Mundaqar since very few of the great cities could maintain their sprawling network of fortifications without a dedicated task force of labor. A few of the largest cities began to transition to permanent, stone fortifications. This was mixed achievement since it was prohibitively expensive to organically expand, unlike the earthworks which could be easily constructed from materials on site.

In the eleventh century, the southern Sultanates of the empire broke away from the new Caliphate and Mundaqar came to be dominated by the Sultanate of Tahir. It was under this Sultanate that !Europeans were first able to establish a foothold in Mundaqar when the Sultan granted them lands on which to build warehouses and invited them to his court to help govern the many ghafil (those "oblivious" of the Tashbith) of the nation and to facilitate the exchange of goods across the ocean. The primary reason that land and legal privileges were granted to the foreigners was to prevent the exhaustion of Tahir's supply of bullion, which, though very large, was threatened by the vast quantities of spices, woods, and other goods from abroad. The supply of land, labor, and the acceptance of in-kind payment of taxes were all part of a system of exchange. Since the primary tax on foreigners was the Jizya, the per capita tax on non-Yen living under foreign law, the Sultans did everything they could to increase the number of immigrants. They built housing developments, gave them villages, and even provided them with midwives. At the same time that the Sultans tried to increase the population of ghafil, however, their courts generally tried to dissuade them from offering up too much land. This resulted in very confined, densely populated communities of foreigners all across the coastal region.

Oubastine Expansion

During the crusades, successful campaigns exposed the borders of Tahir to militant and expansionist neighbors. Initially the Sultans attempted to launch counter-offensives to rescue the Yen living in the former Alban Caliphate, but were rebuffed by the combined efforts of the crusader states. The Sultans were also unable to rely on the soldiers provided by their aristocrats, especially the 'Iifae communities which were opposed to the regnant Sahb denomination. Unable to conquer the "Oberemagha", as the Sultans called the crusaders after their cross symbols, the Sultans began to instead seek out soldiers for hire to bolster their internal strength. These soldiers were often paid in lands, especially in the disloyal 'Iifae regions on the coast. The Oberemagha were also useful in suppressing disloyal members of the aristocracy and clergy who might otherwise have demanded compromises to the Sultan's authority on religious grounds. The loyal corps of Oberemagha also found themselves in the role of managing the ghafil communities of Rezese migrants, which were especially prominent in the lands granted to the Oberemagha.

Several revolts sullied the relationship between the Sultans and the Christian communities of Tahir, especially since many of them formed around disloyal elements of his own army. By way of punishment, the Sultan would seize vast quantities of land from suspected collaborators and relocated 'Iifae villages from inland areas to the coast. This caused substantial conflicts between the 'Iifae and Christian populations in the area which frequently sparked brawls and even pogroms on occasion.

Geography

Mundaqar's geography varies widely from north to south. The northern region is dominated by the Al'zir Jafat Desert, which is most erg in the west, slowly transforming to the dry southern face of the Astral Mountains. Below the desert are grasslands and chaparral that increase in intensity towards the southern tropical zone and Mundaqar's southern border at Lake Upemba.

Politics and Government

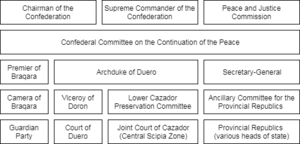

Mundaqar has been under the rule of a transitional government since the peace settlement in 1886 that ended the civil war. The central government's legislative and executive body is the Confederal Committee on the Continuation of the Peace, though their power is partly checked by the oversight of the Peace and Justice Commission. Originally the CCCP was formed to ensure that there was no further fighting after the 1983 armistice, they organized the disarmament of non-essential military personnel, which included paramilitary organizations that had not agreed to the armistice. By the summer of 1984, however, it had emerged as the new centralized military command of the member organizations. The CCCP was mostly empowered by Álvarez's Republican Guard, who worked well with international watchdogs and was able to gain concessions from his former rivals both within the Republican Guard and in the rest of the nation. In 1886, the CCCP was recognized internationally as the rightful government of Mundaqar, though it never officially became the government and has continued to act as a "transitional" body with the ultimate aim of a new centralized state.

Military

Mundaqar's armed forces primarily serve in a defensive and ceremonial capacity, since public opinion has consistently been anti-interventionist and pacifist since the civil war. Each state of Mundaqar maintains its own military force for self defense, including air force and navy, but as vital measure of political stability, all soldiers swear loyalty to the Federation in a public ceremony after the election of a new chairman. Because the military is divided up into ten smaller armed forces, their collective force projection is greatly reduced, especially since only Braqara is able to maintain any aircraft carriers.

Because of Mundaqar's education system, many students at the secondary and post-secondary level are given nominal military assignments. Most of their time is spent on small-scale construction, maintenance, or clerical work, but these graduate units also take on ceremonial duties. At events associated with the Federation at any level, military units are always present. This includes graduations, commencements, appointments, awards, ribbon cuttings, and etc. They are also typically deployed for local emergencies, often floods or fires, to assist or take the place of professional first responders.

Foreign Relations

Due to the confederate structure of the national government, the constituent states of Mundaqar have retained substantial freedom to represent themselves in international politics. Most prominently, the National Republic of Braqara is a considerable force in the promotion of illiberal democracy and the Yen ideology worldwide. Likewise, the Archduchy of Duero de Aqar is a prominent supporter of the Smithic faith and the leading figure in the environmental conservation movement. In spite of the decentralized use of soft power, the central government is also active in international politics, promoting universal disarmament and human rights.

Economy

Mundaqar's economy is a developing mixed market, with some elements of feudal land tenure retained under common law, some elements of a planned economy through nationalized industries, and some elements of a free market. After the end of the civil war, Mundaqar was essentially bankrupt and experienced widespread economic depression. The cycle of recession from 1900 to 1950 involved attempts by various cities and coalitions of cities to rapidly industrialize, mostly financed by foreign debt. The import of capital goods would create a large trade deficit, the devaluation of the Dinar, which rapidly increased inflation. Meanwhile, Mundaqar's primary employment remained agriculture, which suffered from chronic underdevelopment, outdated techniques, and poor breeding stock. Famines were not uncommon in conjunction with recession.

While the general public greatly suffered, equity was continuously concentrated in the hands of the former and current nobility, portions of which actively speculated against the Dinar while other factions more passively accumulated capital financed by sovereign debt. Political machines in the cities, combined with an extremely coercive land-management system in the rural areas allowed this destructive cycle to continue until the 1960s. In 1962, Lucas Saul de Micho's Public Prosperity Party gained power in several prominent cities in the Braqara Republic, which had hitherto been under the control of the Marques of Chite and his allies in the Republican Guard. The PPP began and expansive range of reforms which began with the nationalization of noble assets. While the PPP's redistribution schemes greatly reduced income inequality in the short term, it's most important innovations were the land-management council, which was a board of agricultural workers and managers, and the establishment of small agricultural schools located at the periphery of parent cities.

The PPP's early agricultural and educational reforms helped develop the Braqara economic model, which is why that constituent state has since grown to encompass all non-royalist states in Mundaqar. Despite initial success, the PPP was not able to retain power in the long-term since they ultimately failed to satisfy the nation's demand for an industrial-scale manufacturing and service sector. The Braqara model, however, endured to subsequent administrations and forms the backbone of Mundaqari economic planning.

Energy

Because of a lack of local fossil fuels the relatively late development of the national power grid, most of Mundaqar's power comes from a mixture of nuclear and renewable power. The largest contributor is hydroelectricity (35%), followed by nuclear power (25%), solar power (15%), fossil fuels and some unique energy projects (ie the Grajal wave generating station) make up the remaining 25% of energy needs. Most energy generation is centralized in Braqara, which exports energy to Duero and Las Faldillas. Las Faldillas notably has no hydro power plants and only operates coal and oil powered plants.

The Confederal Commission on the Circulation of Power oversees the exchange of electricity between the constituent power grids. Members of the CCCP are appointed for a ten year term by the Chair of the Confederation and confirmed by the Committee.

Healthcare

The largest sector by employment in Mundaqar is healthcare, which accounts for 15% of the workforce and 25% of the GDP, partially as a result of the extravagant public health spending in Braqara and partially from mass-employment schemes for the elderly and unemployed. Women are disproportionately steered into healthcare careers within their local community and are paid extremely low wages to offer basic health services to the infirm. Hospitals are centrally located in large communities, but most communities in Mundaqar are within driving distance of an outpatient facility or a nationally funded clinic. Other healthcare facilities are often combined with other community services such as gymnasiums or performing arts centers. Often these facilities are staffed by part-time workers who provide nutritional advice, lead exercise programs, or even dispense folk remedies. Because of the part-time staff and multi-use buildings, Mundaqar has consistently sacrificed quality of care for access to care. There are relatively few fully-licensed physicians in rural Mundaqar and many communities with fewer than 10,000 residents lack adequate physicians. To compensate for this loss, there are many lower grades of physician who are trained on a semi-regular basis by more qualified doctors. Many communities have teams of semi-professionals and students providing day-to-day care.

Approximately 7,000 fully licensed doctors complete their training each year, but less than half of them received all of their training before beginning to practice. A majority of new doctors received at least some "field training" by learning and practicing in their communities before attempting to be licensed by the state. There are only 80 medical schools in Mundaqar, but there are over 50,000 registered doctors who spend at least two weeks a year teaching community practitioners.

Agriculture

Approximately 12% of Mundaqari are employed in agriculture. The majority of agricultural workers are subsistence farmers, heavily concentrated in the fertile Las Faldillas region. Only 2% of the workforce is engaged in industrial scale farming, which produces most of the food in the nation, though Mundaqar is not self-sufficient on food. The Yen taboo on fishing has resulted in a stunted aquaculture and most fish is imported.

Las Faldillas has struggled to eliminate subsistence farming and consolidate farms into at least surplus farming. The feudatory culture and archaic real estate laws have made this difficult, however, and many local governments have instead tried to capitalize on the bucolic towns as a destination for tourism. Constant efforts at reform have either implements more regressive hereditary land laws or progressive, corporate and large-scale farming. The turmoil has disrupted businesses on both sides and kept the small provincial republics from fully developing.

Demographics

Mundaqar is a multi-ethnic state, but has a plurality of the Aljito peoples of the historic Cazadori kingdoms. The Azdarin empires introduced large minorities of Sosafari and North Scipians, which persist today in the heartlands of Dahkma. Interspersed with these groups are the Oubastines, who controlled Mundaqar in the early modern period and have been partially assimilated into the local society.

Education

Education begins at an early age in Mundaqar since most families form little groups to employ daycare workers, often a single woman or widow in the community. Young men also learn to read and write Wenarei from their local Qadib. At the age of five or six children begin their primary schooling, which is provided for free by the state except in select jurisdictions of Las Faldillas where education is provided by the church. After four years of education, children now aged eleven to twelve can continue for another six years at a public school, after which they are required to spend time in public service. Some children, mostly based on their grasp of Wenarei, are invited to attend special secondary schools attached to Yen Universities. Most parents, to avoid the public service period for their children, opt for private schools where they can learn trades.

The most prestigious learning institutions are the Yen Universities. These schools are extremely selective and depend on recommendations from local clergy and teachers for admittance, though there are also a few opportunities for open applications and heritage applications. They also operate special secondary schools from which they draw a large portion of their students. There are secular schools, both public and private, though most private universities in Mundaqar have a reputation for providing exceptionally poor instruction. Public schools are not free, though a substantial portion of the tuition can be waived for a public service period following graduation.

Religion

The vast majority of Mundaqar is Yen, mostly Sahb, but the religious minorities are actually pluralities within their own republics of the federation, giving them a disproportionate voice in national politics. The pluralistic form of government is, however, seen as an important part of the peace and is generally supported by the Yen majority. 92% of Braqara is Sahb Yen, 60% of Duero is Christian, and 35% of Las Faldillas are Christian.

Prior to the 10th century AD, many Mundaqari adhered to animistic traditions closely associated with their language and kinship groups. Several of these religions formed the basis of a kind of proto-national identity in the great cities, which had formal non-lineal organizations based on craftspeople who manufactured charms and religious implements. These craftspeople provided their monarchs and leaders with their wares for free, which in turn created demand for their goods, but also exempted them from taxation. This mercantile clergy contrasted sharply with the shamanistic traditions of the river cities which involved communication with spirits and accessing higher realms. Some Ịkwado philosophers and alchemists syncretized the two religious groups into Ngwugwu or Aljito Mysticism, but it was never a popular faith. All three groups, as well as many minor faiths, were swept aside during the empire and Azdarin became the dominant religious force.

The 'Iifae became an ostracized group almost as soon as they became established on the west coast. Initially they had great success in joining established river communities where they quickly became a dominant force thanks to their organization and collectivized wealth. Meanwhile, the Sahb had the unenviable task of toppling the strong, well defended great cities of the interior. While ultimately successful in this effort, as many as 1/4th of the western citizens of the old empire were deemed heretics by later Caliphs. In order to control this population, the Sahb lords began to employ Christian mercenaries from the north and from trading companies. The Sahb much preferred the Christians, who could be heavily taxed, to the 'Iifae who acknowledged the divinity of the prophet and could not therefor be treated like pagans. While the Sahb and 'Iifae shared the same gods and prophets, the 'Iifae proved to be unreliable allies in the Sahb conquests, their teachers often refused to approve or adopt state doctrines for the faithful, and perhaps worst of all, they produced very few riches. At first the 'Iifae were merely expelled from the cities to make room for more productive citizens, but as the needs of the cities grew, demand for space in the countryside increased as well. Christians, which the Yen called Oberemagha, were often allowed to seize land from the 'Iifae if they paid a tax on the land and worked it for a set number of years. As a result, many of the old 'Iifae communities were replaced by Oberemagha and even today 90% of 'Iifae in Mundaqar live under explicitly Christian governments in Las Faldillas or Duero.