Music in Themiclesia

Music in Themiclesia has a lengthy, celebrated history and presence in Themiclesia. The earliest records of music are inherited from the first settlers' Menghean progenitors, though innovations appeared within and beyond the Menghean musical canon with earnest and variety in time. As with many other things, the Themiclesian state thought of music as a Menghean tradition requiring preservation but did not discourage its use in other settings according to contemporary trends. It has been a peripheral but long-standing subject in the traditional educational curriculum for gentry and later the public. Music is commonly found in dramatic and poetic works or in their own right as a form of art, and there exists a sizeable commercial market in the distribution of music.

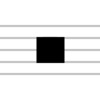

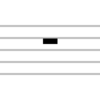

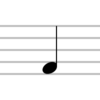

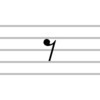

In its most traditional form, music was given a philosphical function of instilling tranquility and happiness in both the player and listener; these properties, in turn, granted it political significance, in service to the ruler's duty to spread tranquility and happiness throughout his realm. In the centuries following the fall of the Meng Dynasty in 278, a considerable but incomplete corpus of music and lyric poetry set to music accumulated in the Themiclesian court. Amongst these are the Classic of Poetry and Classic of Music, both dating to the 10th Century BCE and complementary (lyric and music) to each other. Musical theory also continued on the foundation laid down in Menghe's classical antiquity, distinguishing 12 notes to one octave. The traditional instruments are classified into eight categories according to the materials they are composed of—bronze, stone, leather, earth, silk, bamboo, wood, and gourd—falling into the modern categories of strings, woodwinds, reeds, and percussions.

Since its taking root in Themiclesia, external influences have left visible marks on non-canonical music that evolved with contemporary tastes. The earliest influences came from Buddhism, a Maverican import; the rhythmic chant of Buddhist classics introduced more variety to the Themiclesian tempo, which until then consisted of only full and half tones. In more recent ages, the introduction of Casaterran music theory has further widened the scope of musical variety in Themiclesia. The presence of a twelve-note octave in Themiclesia made transposing concepts (such as scales and chords) from Casaterra into Themiclesia virtually seamless. Into the 19th Century, musicians in Themiclesia composed according to both traditions and sometimes mixed the two. After the 20th, popular music from foreign states have become mainstream in Themiclesia, particularly after the Pan-Septentrion War. Conversely, Themiclesian performers have also enjoyed a degree of recognition in foreign audiences.

Trends by era

Before 1600

1600–1800

1800–1900

1900–1930

1930–1947

1947–1957

In the first decade after the conclusion of the war, the Yellow Plum Tune (黃梅調, gwang-me-tiawh) grew phenomenally popular. Originating from the Yellow Plum County, it combines a simple theme with a multitude of variations to produce an iconic melody, to which lyrics written in poetry were set. Such songs became popular throughout the Army due to their bright, cheerful timbre and memorable lyrics, as well as the paucity of musical instruments, all quite affordable, required to play the melody. Many officers, in an effort to demonstrate their literary ability, wrote lyrics for the tunes, which the troops would retrieve and set to a tune they thought was fitting for the lyrics. It would become a staple of bonding activity between officer and soldier in the years to come. When the conscripts were demobilized in 1946–47, they brought Yellow Plum Tune home, where it found an equally enthusiastic civilian audience. A columnist wrote of it as the "best cure for the sadness accumulated during the war".

Though originally a style meant for a singing chorus, it was also applied in theatre. The spread of television sets during the early 50s permitted theatrical performances to be received in the comfort of the domicile. No longer limited to a physical audience and venue, such operatic works were given a cinematic interpretation, creating the Yellow Plum Movies that remained in vogue for more than two decades. These movies generally did not seek to emulate reality or experiment with novel filming techniques, and most dialogues were delivered in singing; hence, some consider them more of a musical than movie. Yet others have remarked that the transition from an opera broadcast to its final form in the late 60s is certainly one of increasing cinematic portrayal, even though the earliest ones only used camera movements to follow actors as they moved across the set.

Due to the sheer number of foreign troops stationed in Themiclesia from 1937 onwards, tastes from abroad also seeped into the Themiclesian social fabric. Rock & roll, a new style from the Organized States took to a small but faithful following by the early 50s.

1957–1963

The incredible popularity of Yellow Plum music inspired some Themiclesian musicians to innovate a new style that combined the virtues of Yellow Plum and the rising trend of Rock & Roll. Up until this point, most Rock & Roll songs were written in Tyrannian, which meant that a significant section of the populace could not understand it. Musicians therefore began penning songs in Shinasthana, following the same poetic rules that existed in Yellow Plum, and set them to Rock & Roll tunes. Though initially faced with a lukewarm reception, it became quite popular with the generation born during the war, as it was perceived as more fashionable than Yellow Plum, which was more than anything a statement of warmth and consolation. The melody of these hybrid songs also incorporated some of the more familiar rhythms in Yellow Plum.

1963–1968

In 1963, Themiclesian musicians writing Rock & Roll songs started to find the demands of poetic lyric restrictive. More specifically, Shinasthana words were metrically either "long" or "short", and in lyric poetry the first and second lines must have opposite meters, while the second and third similar, third and four opposite, and so forth; this is in addition to the end-rhyme requirement, which was on the fianl character in every first, second, and fourth lines and which must be long, while the third line must not rhyme and end in a short syllable. Writing melody that suited the metrical properties of the lyrics was also unduly challenging. Thus, from 1963 onwards, musicians began a trend called "free rock", referring to the abandonment traditional metrical lyrics. Though initially criticized for its "liberal dispensation of meter and musicality", the Tyrannian Invasion soon commenced and supported the new format through its expressive and free composition.

For most of this period, songs in both Shinasthana and Tyrannian were popular and often broadcast from the same stations. By 1968, however, the relatively mellow Rock was augmented with a style today known as Hard Rock. Themiclesian musicians rarely wrote songs in the style of Hard Rock for its relatively percussive melody, which was then seen as incompatible with the monosyllabic nature of Shinasthana; the expression of darker themes (which gives rise to Metal) was also censored by the music community for fear of public opposition. Soft Rock therefore flourished in Themiclesia as a continuation of the 60s style.

1968–1975

Between 1968 and 1973, the introduction of the Hippie lifestyle co-incided with the trend towards Soft Rock after the split of Rock & Roll in 1968. Hippies at this time demanded more unusual, soothing forms of music, which Soft Rock was able to provide with its playful vocals and harmonious chords, without losing a sense of trendiness. While the anti-war statement was in full swing, another undercurrent with the opposite statement grew in popularity, though it would not threaten the dominance of Soft Rock until 1973. Surprisingly, metrical lyrics made a minor comeback; some commentators found that metrical lyrics gave a sense of structure to a song that otherwise was too "flat", while others claim that it was merely nostalgia. These meters were not the same as the ones a decade ago, being less strict and generally did not demand rhyming.

The genre of Soft Rock began to incorporate themes and techniques from Casaterran Classical Music and Folk Music to appeal to a more cultivated audience, as the post-war generation that listened to Rock & Roll matured into adulthood. For this reason, some forms of Soft Rock, mostly the conventional ones, may also be called Adult Contemporary. Some bands also replaced the canonical electric guitar with acoustic ones to provide a more resonant, rich tonality. Sophisticated melodic development and highly emotive lyrics that did not always express its true message directly represented the mainstream taste of the early to mid-70s.

1975–1982

With the outbreak of Punk in Tyran in 1975, the contagion spread...