Road and Path Maintenance and Regulation

Road Improvement Manual (RIM) was a book describing how roads and paths were to be built and maintained, first published in 1951 and then semi-regularly updated, by the Kien-k'ang Council Roadwork Division. It is the first manual of its kind to be published in Themiclesia, giving general guidance to the construction and maintenance of roads.

The first editions of the Regulation targeted only the road surface itself, but since the 1977 updated it has incorporated underground facilities as well. Since its publication, it has been served as source material for similar manuals published by other civic authorities in Themiclesia.

Background

General history

Kien-k'ang history has resulted in a largely unplanned network of both regulated and unregulated roads that served a city pushing 6 million denizens in 1950. Some roads were laid down by decree that remain in force and still govern some aspects of the thoroughfare; others were built under contracts between the civic authority and investors or speculators; still others formed organically, sometimes simply from the "negative space" between private, walled-off areas and other times to provide access to a public or private facility. The maintenance work of this network was hitherto done mostly by individual application to the Kien-k'ang Council, though the central government or private individuals were responsible for the maintenance of specific roads.

Motoring age

With the advent of motor vehicles en masse by 1925, the regulation and maintenance of roads for motor vehicles was acknowledged an eventual necessity, but the outbreak of the Pan-Septentrion War in 1932 caused the City to put the idea on the back burner, instead focusing on civil defence. After the war, the importation of cars was under an enormous, 100% excise as a luxury good, but this tax disappeared in 1952, and cheap foreign cars flooded the city almost overnight.

The arrival of cheap cars elevated novice drivers-cum-commuters to predominance in the driver demographic, over experienced drivers who drove limousines, taxis, or trucks for a living. Amongst the problems immediately emerging were those of driving vehicles into impassable streets, crashing into arcades, and falling into open drains; traffic accidents increased by 232% between 1950 and 1955. The City first blamed the fact that many drivers were novices or from out-of-town, but eventually citizens demanded the government provide a better environment for cars, a demand that underlay the 1957 Road Improvement Programme (RIP) by the Road Improvement Board (RIB).

The Road Improvement Manual (RIM) was therefore intended as a general guide describing the type of road network that the city intended to create via road creation and maintenance.

Road classification

The first edition of the RIM, which was effective in Kien-k'ang, only divided thoroughfares into footpaths (for pedestrians only) and roads (for all traffic). This designation was unitary: the entire length of the path was either a footpath or a road. To be classified as a road, it must be at least 3.2 m wide and have no geometries that make turning impossible for wheeled vehicles. While the concept of a road hierarchy was argued for, it was not a practical option or outlook in built-up Kien-k'ang.

After the thoroughfares were classified, routine maintenance work was carried out according to its classification. Improvements were also planned largely according to the classification, usually without attemting to convert one type into the other.

It should be noted that the RIM classification was an engineering classification, not a utility classification. RIM does not distinguish roads based on their capacity or environs but only stipulates that certain basic standards should be met, such as weight-bearing and water-shedding ability.

Road and property numbering

While most medieval roads that connected two specific places or those built as malls usually had names, such was not the case for many organic alleys.

Road design

Pavements

- Where a road is designated for vehicular running, a pedestrian path shall be provided for their right-of-way, and such path is to be physically separate from the surface designated for vehicular running. It shall not be narrower than the lower of either one fifth of the width of the surface designated for vehicular running or 1.15 metres; notwithstanding the previous, the pedestrian path shall not be narrower than 0.7 metres in any case whatever.

- Where a road is not designated for vehicular running but where vehicles are reasonably expected, a pedestrian path is encouraged to be provided within the same parameters.

Vehicular running

- If a road is designated for vehicular running, the vehicular surface is to be sealed with tar; conversely, the pedestrian path that adjoins the vehicular surface shall not be sealed with tar.

- If the vehicular surface is divided into lanes for the purpose of parallel running, each lane shall not be any narrower than 2.49 metres.

- Where at all possible, a road shall not be designed to have different quantity of lanes separated by an intersection so as to require them to merge in said intersection.

- Roads designated for vehicular running shall be free of all curves, grades, and other obstacles that vehicles cannot navigate without causing unreasonable stoppages or hazards.

- The speed at which such imperfections are cognizable is standardized at 20 MPH (1971 altered to 24 MPH), unless a posted speed limit is higher.

- The surface designated for vehicular running shall be free of vehicles stopped for an unreasonable amount of time.

- Intersections between streets designated for vehicular running shall be controlled.

Effects

One of the larger remodelling projects carried out under the RIM is the interface between South St. sections 2 and 3, where there is a dramatic difference in street width (section 2 was 40 foot across, section 3 was 132 foot) but no difference in lane number (4 on both sides).

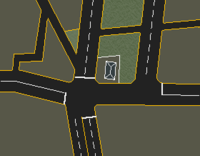

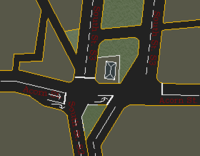

Section 3 had been widened in 1874 to accommodate a large gardened median at the initiative of Lord But and a number of other patrons. Section 2 was widened under a different initiative in 1948 so that the road could accommodate two lanes in either direction. The issue (as illustrated to the right) is that the widening of section 3 was carried out asymmetrically with the result that the northbound half of section 2 now looked directly into the southbound half of section 3, whereas the northbound half is so far misaligned as to be nearly completely out of sight.

While accidents were not noticeably common at this intersection before the PSW, they became very common after the war. As the signal was not controlled, and with increasing traffic speed, head-on collisions (as many as 62 instances in 8 years) were unfortunately often fatal. Locals blamed drivers from out-of-town for not understanding the northbound side of the street was off to the east. Mak, who was fined in 1955 for driving on the wrong side of the road, sued the City saying that the intersection had induced him to drive on the wrong side so he should not be fined; while the case was dismissed for the reason that drivers are responsible for observing the rule and custom of the locality, this intersection was earmarked for improvement as a result.

Since there is a temple in the gardened median on section 3, it was decided to pull down two buildings on section 2 in order to deflect the northbound traffic and orient it towards the northbound side on section 3. A new lane marking was also added to show those turning left on Acorn St. not to to turn into the wrong side of the street; this was also an easy mistake if a car was turning right at the same time from South onto Acorn St.