User:Devink/sandbox5

| Battle of Tanjavi | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Part of Indran War | |||||||

The Indra Delta where the battle took place | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

| File:Azcapotzalco ZP.svgAzcapotzalco |

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | |||||||

| File:Azcapotzalco ZP.svg Tlahtohcapilli Capotzilic |

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| File:Azcapotzalco ZP.svg 12,000-20,000 |

| ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| File:Azcapotzalco ZP.svg 300-500 killed |

| ||||||

The Battle of Tanjavi took place during the dry season of 1652, in southern Pavirata between a coalition of Dhatmani principalities against a Tepanec army led by Prince (Huehuetlahtohcapilli) Capotzilic. The Paviratan attacked the Tepanecs while they were traversing the Indran Delta, on their way back from a raid they had accomplished deeper inland. Poor coordination and distrust among the members of the Dhatma led to a Tepanec Victory and the disbanding of the Coalition, puting an end to all pretense of Dhatmani unity and kickstarting a period of chaotic inter-princely wars.

The Tepanecs had landed at the start of the dry season and burnt a path of destruction through some of the richest lands in the Indran Delta, home to a complex of agrarian dravidian groups. The Tepenecs then traveled north, up the Indran river, sacking many towns along the way. They had retreated back south, their boats and baggages full of loots. While they had outrun the Coalition, the Tepanecs were forced to stopped because the Indran Delta's waterways had shifted since they last came and they had to navigate the dense swamps to find an actual passage to the sea. This slow-down allowed the Dhatmani to catch-up. Capotzilic had his army prepared a defensive position on a hillside near Tanjavi, surrounded by swamps and canals.

While vastly outnumbered, the Tepanecs were all experimented soldiers, were better organized than their opponents, and enjoyed an excellent defensive position greatly reinforced by their engineers. After a brief artillery battle, the Paviratan rocketeers were routed by the Tepanecs cannons, entranched on their hill. The Paviratans then launched a series of desorganized charges, which were broken up by the lack of coordination between the different forces making up the army, by the swamps and water ways channeling them through obvious and muddy paths, by having to charge uphill, and by the pits and trenches dug by the Tepanecs. The Paviratans were then victims of the Cuāuhocēlōmeh counter-charge and, once they had started to flee, were pursued by the rest of the Tepanec army. Attempts by the Paviratans to regroup and counter-attack were nipped by the Cuauhocelomeh shock troops, allowing for the Tepanecs to continue pursuing and capturing enemies for the next few hours without risk.

Defeated, the Coalition disbanded almost immediately, each Prince returning with his remaining forces on his own to his state. Informed of this, Capotzillic decided to, rather than return immediately to the Empire of Azcapotzalco, lay siege to the city-fortress of Titukuddi, which controlled the access to the Delta and thus to the Paviratan inland. Titukuddi fell the following year and would became an important launch pad for further raids and expeditions in Irathava.

Background

Between the years 1530 and 1560, the recently independent Pavirata had aimed to spread the Dhatma faith to Nepantia in two different occasions. These campaigns proved to be costly, both in ressources and human lives, and brought no benefit to the Dhatmani, having lost almost all of their fleet to a storm the first time, and being repelled by a coalition led by the Empire of Azcapotzalco the second time. These defeats weakened the Vatram Monarchy's position as the Hegemon of Pavirata, and a process of decentralization and weakening of the theocratic structure started.

Meanwhile, the Empire of Azcapotzalco was also facing inner difficulties : the sudden expansion of the Tepanecs to the west had not been the economic nor the political success the Huetlatoani had hoped for. While the Nawals remained loyal and satisfied with the Huetlathocayotl, they were a distant excalve and contacts with it had to be constantly protected against Xiuy raids. On the other hand, the Teenek proved to be unruly vassals, questioning their submission now that the Dhatmani threat was gone. Revolts and rebellions had to be put down, which was complicated by the fact the mountaineous kingdoms that separated Azcapotzalco and the Inik region were also ennemies of the Huetlathocayotl. All of this diverted men and funds away from the central regions, which hadn't yet entirely recovered from the Teltetzaltin Plague. This led to a Civil War and then a Succession Crisis endin in 1623 with a change of dynasty.

Ahuachpitzactzin (1544-1575) was the second ruler of this new Nezahualid Dynasty who titled themselves as Huehuetlatoani. Like all Emperors before him, he started multiple campaigns against rebels and other pockets of resistance to his rule, as a show of strength. But to really secure his rule and his dynasty, he made his son Capotzilic ruler of Michpan on the western coast, with the goal to prepare and execute raids on Pavirata. traders gave the Tepanecs a detailed description of the Paviratan coastline and of its wealth, and in 1649 diplomats were sent to various coastal principalities, to convince them to pay a tribute to the Huehuetlatoani in exchange for protection. Their offer was rejected, which gave the Tepanecs the casus belli they needed. Capotzilic continued to gather his men and fleet, and in 1652 began his campaign.

Prelude

Despite the messages sent by the ambassadors, only an handful of coastal principalities had made any significant preparations against a possible Tepanec attack. Capotzilic and his men thus managed complete strategic surprise, landed near the Paviratan Delta and razed every town in their path and looted whatever they could from the populace. After a month of pillage, Capotzilic sent back a portion of his fleet to Michpan, laden with loot, with orders for reinforcements, supplies and money to be collected, embarked and loaded respectively, before the fleet rendezvous with his army at a predetermined location and date. He then took his men on small riverboats and moved upstream, to the densely urbanized inlands.

The Dhatmani principalities were too distrustful of each others to present a common front to the pillagers. Some cities, both in the Delta and the Inlands, preferred to just pay the Tepanecs so that they would avoid their lands. But other cities were in uproar, swollen by refugees, and in disbelief at the relative ease at which the idolatrous and bloodthirsty Tepanecs were seemingly tearing through the lands, flaunting their ability to march at will through Pavirata, obviously in the goal to gain more tributaries. These cities united around the banner of Vatram, who ordered all able-bodied Dhatmani to join them in a just war against the Ennemies of the Faith.

The Coalition gathered, and all took an oath to crush the Tepanecs so that they would never return to their lands. Informed of the incoming army, Capotzilic decided to abandon the campaign and return to the south to meet-up with his fleet. He successfully managed to outrun the Paviratans and reached the Delta first. He would then have seemed that the Tepanecs would've been free to return to the sea without consequences, but the many chenals of the Paviratan Delta are treacherous and often change courses through the dense swamps and wetlands of the region. This slowed down the Tepanecs greatly, and allowed the Paviratans to catch-up. His troops already weakened by diseases and illnesses, Capotzilic decided to make camp on an easily fortified position that jutted out from the swamps, and wait for the Paviratans there.

Opposing forces

Tepanec Army

Capotzilic's party was mostly made up of various Nahuatl-speakers (Tepanecs, Acolhuas, Tenochas...) but also of Ñuhmu mercenaries. Contemporary estimates vary widely, generally between 10,000 and 20,000 men, if not more. Almost all of them were veterans : the number of carriers had been limited to a strict minimum through the use of riverboats and horses. There were no youth or adolescents soldiers, only commoners who had already participated in at least one battle before (the "Yaoquizqueh"), themselves led by "Captors" (Tlamanih). Most of these Yaoquizqueh were Tequihuahque, expert archers, gunmen, and artillerymen.

Above them, there were the first elite troops of the Tepanecs : units made of Cuextecameh, "Twice Captors", led by Papalomeh (lit. "Butterfly", so called because of the banners they wore on their backs). And finally, the "shock troopers" of the Tepanec army, kept in reserve to support any weakening of the defense during the battle, or to exploit any opportunity presented by the ennemy, the "Cuāuhocēlōtl, the famous Eagle or Jaguar Knights, identifiable by the skins and feathers they wore. They were composed of sons of the Tepanec nobility who trained all their lives in the strict reglemented live of their Knightly brotherhood, and by commoners warriors ennobled because of their bravery and great strength.

Most of the soldiers wore full or partial ichcahuipilli, gambesons of cotton soaked with saltwater and then dried so that the salt would crystalize inside the cloth. Above it, they wore cuirass made out of iron or steal, alongside other pieces of armor. Only the members of the knight orders had Cuacalalatli, helmets carved out of hardwood to look like different animals or deities and reinforced with iron plates or nails. Other soldiers had to do with thick padded cotton hats, or no helmet at all.

Since the Totonac Wars, the Tepanecs had increasingly integrated firearms and artillery to their armament. In 1651, they were well equipped in matchlock, handled by the veterans Tequihuahque, but also possessed Culverins and bombards, most of which had originally been mounted on boats, but Capotzilic had ordered they'd be removed from the ships, to reinforce the Tepanecs's defenses.

Paviratan Army

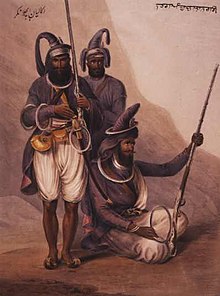

The Paviratan army was led by the Vatramic princly heir to the Xanda dynasty, Prince Jivan Singh Xanda. He however led a loose, mostly fractured alliance of Prince's vying for power and under constant suspicion of one-another. Prince Jivan tried desperately to preserve local Vatramic power. In order to muster up to 50,000 troops, Jivan had called for a war to defend the holy land and expel the Tepenecs. It was under this brief period of unity, in an effort to re-unite Pavirata, that thousands of Akali holy warriors descended from the highlands for Jivan. Many were inspired by formerly exiled Prince, as an outspoken critic of the Invasions in Nepantia and member of the growing Dhatmani pacifist faction, he made clear that the battle ahead was unavoidable and a duty.

The majority of the army was composed of devout Dhatmani warriors, local levies quickly assembled by the Princes. Dhatmani warrior culture was deeply ingrained throughout the principalities, making for quick mobilization. Both men and women were encouraged to practice arms and other warrior principles on a daily basis by the dominant Krisala sect, led by the Akali. Both Akali highlanders and local conscripts were armed with some matchlock guns, with a large amount of rockets as well. Most Akali warriors were expert light warriors and skirmishers, mostly employing guerilla warfare.

Akali warriors wore lofty, tall turbans that are steel-enforced tiered with chakrams. The color of their attire was dependent on which Dhatma practice they belong to. They wore iron chainmail under an iron breatplate, some also wearing iron war-shoes. Traditionally, the Akali had mostly favored the Khanda but by this time had begun using the lighter and much longer talwar. In addition, Akali warriors would be fully armed with a kirpan shortsword and some other dagger. The primary weapon of choice around this time was the paviratan musket.

It is estimated that the Prince's army also had 2,000 to 5,000 rocketeers, supplementing a lack of readily available cannons due to being unable to easily move artilery through the swampy Indran Delta.

In-part of what made Prince Xanda's force so quick to catch the Tepanec's was the use of small boats to navigate the Delta and harass the invaders.

Battle

Preparations

The Tepanecs had fortified a small land position surrounded by swamp. They made quick ramparts and small trenches as fortifications and had spent days dangerously moving their cannons into position. Akali scouts would observe the Tepanec construction, eventually early arriving skirmishers would begin harassing the defenders, then slip back into the swamp over the course of several days.

Maharaja Jivan Singh ordered the Akali to continue harassing the Tepanec as he brought his forces into position. Maharaja Raakesh Singh Nakeer, of the Srikhan Awsa dynasty, disagreed and thought a full attack with rocketeer support was needed to shock the enemy and catch them off-guard. Jivan ordered Raakesh to stand down and relunctantly he did, keeping the alliance in-tact for now. Jivan's plan was to attack the Tepanec's was mass waves of rockets from a distance, with more consistent Akali attacks to slowly wear the defenders down and break their morale. In this, Jivan planned to simply encircle the Tepanecs and wait, believing consistent rocket attacks, skirmishers and disease would break them.

Artillery battle

The Paviratan army moved forward to encircle the Tepanec position, their river boats navigating the trearcherous waters of the delta. The rocketeers were moved forward, to harass the entrenched pillagers. Because the swamps offered no ground to place and prepare their rockets on, they remained on their boats, and used them to launch their missiles. However, despite the long range of their weapons, up to two kilometers in the hands of trained rocketeers, its inherent lack of precision meant these first salvos had little effect. Some units decided to get closer, defying the swamps in their search of a good vantage point. This, unfortunately, placed them in range of the Tepanec artillery, whom waited for the river boats to stop to launch new volleys of rockets, before firing. The rocketeers retreated, unwilling to risk a direct confrontation when their boats offered such easy targets for the Tepanecs gunmen, but the small meanderous waterways slowed them down greatly. It is unknown how many rocketeers were lost, as the distance made both rockets and cannons imprecises, but many river boats had been lost, alongside most of their equipment if not their crews.

The Assault

Despite the rocketeers being pushed back, the rest of the Paviratan army continued to move forward. Against Jivan's orders, Raakesh decided to organize and lead an early assault, followed by a number of Sikrhi princes who also wished for the Tepanecs to be immediately crushed. But distrust among them led to the Vatram Prince Ikshan witholding his troops at the last minute. Seeing this, Raakesh would do the same but miscommunication would leave the rest of the army to continue the assault, unaware of the two princes' change of heart and that their attack was already crackling.

The assault was disordered, broken up and slowed down by the swamp and the artillery shell. It's only once the Paviratans had started reaching solid ground and were at a decent range that the first line of Tepanecs gunmen fired at them. By the time the tight formation of Tepanecs soldiers received the Paviratan charge, it had lost much of its impetus.

The battle was chaotic as the Paviratans, whom had already lost their formation, were trying to take over the first remparts and trenches. The Tepanec frontline fired one last volley before dropping their swords and raising their shields and spears. After minutes of a confusing melee, the Paviratans started to show signs of wavering, which is when the Cuāuhocēlōtl were introduced to the battle, charging right through the Paviratans, which was the last straw. Already demoralized, they were now panicking and started to flee and then it was a route. Immediately, the first line of the Tepanecs pursued them as far as they could, using masses and heavy clubs to capture them. The second line, made of veterans of higher ranks, remained on standstill in case of a counter-attack. Similiarily, the Eagle and Jaguar knights continued to roam the battlefield, to immediately crush any attempt by the Paviratans to reform.

Casualties

The losses in the battle were highly asymmetrical but contemporary sources agree that Tepanecs casualties were very low. The more credible estimates vary between 3 to 500 deads, less than a thousand in all cases. Meanwhile, the exact numbers of Dhatmani soldiers who died during the battle is hotly contested, with wide varying figures. Most estimates ranges in the thousands of casualties, but all agree that once their victory was secured, and even during the close-quarter combats beforehand, the Tepanecs seeked to capture as many prisoners as they could, tempering their pursuit of the Paviratans. As a result, it is possible that only a few thousands Dhatmani died during the battle, but many times more were taken as war captives and brought back to Azcapotzalco later on, to serve as slaves or sacrifices.

Aftermath

Tanjavi was a surprising victory for the Tepanecs, and a political catastrophe for the Dhatmani Coalition. The Tepanecs benefited greatly from the indiscipline of the religious warriors and the division of their leadership and the battle could've been without greater strategic meaning if it wasn't for the immediate collapse of the Paviratan leadership. The battle and the following Siege of Titukuiddi would end the idea of a Dhatmani Unity among the divided kingdoms of Pavirata, and prevent it from re-emerging for the next decades. The cripple, divided, Dhatmani armies would continue to fight each others and themselves for weeks before Prince Capotzilic was able to take Titukuiddi and, with it, the entire mouth of the Indra.

Dhatmani Battles

Maharaja Raakesh would flee the battlefield closely followed by Ikshan. The two were in a race to Titukuddi. The Vatrali’s army would cut Raakesh off. Ikshan at this point had wanted to confront Raakesh, believing he conspired a failed assault, though he was the first to hold back his troops on this suspicion, believing it was a faint. Raakesh wanted to fortify Titukuddi before Jivan’s loyalist to militarily control the mouth of the Indran Delta.

The two rushing armies outpaced Jivan, who had lost communication with the other Maharaja’s and remained in a defensive posture against the Tepanecs. A message from Ishkan arrived days later, stating that he believed he was about to engage in battle with Raakesh. Jivan started north, now followed by a recuperated Tepanec army. Jivan was slow, cautiously organizing his army.

Ikshan and Raakesh’s armies would meet outside of Titukuiddi, Raakesh unable to fortify in the stronghold before being cut off. The open field battle would take place on sloped terrain, surrounded by sparse forest. Ikshan had the high ground and largely dictated the battlefield with even more aggression than Raakesh.

The two started skirmishing, mostly in the surrounding forested flanks. This methodical phase lasted several days before Raakesh, upon news that Jivan was coming, ordered retreat from the battlefield and toward the swamp, at Jivan. Ikshan followed in pursuit hastily upon realizing Raakesh fled the opposite direction. It was from here Raakesh staged a guerilla defense in the forested swamps. First ambushing Jivan’s forces, pushing his back against the pursuing Tepanecs, then halting Ikshan from the north doing the same. He was now avoidant, dancing around confrontation while dragging Jivan’s armies around and slowly depleting them.

All were running low on supplies and Jivan’s force had seemed trapped between the Tepanec and Raakesh. Ikshan had then abandoned the battle, fleeing north to Titukuddi. Jivan would eventually surrender to Raakesh, who would take him prisoner and follow Ikshan north, who had already reached Titukuddi, setting a staunch defense from inside the city-fortress’ walls. Raakesh was in a rough position - with a starving, diseased army in survival and the Tepanec’s still approaching as a reformed force. Then to the north, Ikshan controlled the Delta's fortess city at the mouth of the Indran.