Liberto-Ancapistan: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

No edit summary |

||

| Line 77: | Line 77: | ||

Between 2,100 and 1,900 BCE most cities in the Cemsor Valley were abandoned, or reduced significantly in size. Most modern archaeological research suggest localised climate change as the primary cause, most significantly a large southward shift in the upper cause of the river, which destroyed centuries-old irrigation networks and deprived cities of access to water and commerce. This course shift was accompanied by a period of increased temperatures, damaging surviving harvests. | Between 2,100 and 1,900 BCE most cities in the Cemsor Valley were abandoned, or reduced significantly in size. Most modern archaeological research suggest localised climate change as the primary cause, most significantly a large southward shift in the upper cause of the river, which destroyed centuries-old irrigation networks and deprived cities of access to water and commerce. This course shift was accompanied by a period of increased temperatures, damaging surviving harvests. | ||

Considered the end of the Cemsor River Civilisation, the events of the 2,100-1,900 BCE period did not end the usage of Kisin, which survived in a much-diminished output in smaller settlements. Areas connected by trade to the Cemsor valley, most notably western Libertarya, were little-affected by the climatic events in Nizmstan. By middle of the 2nd millenium BCE the city of Padisra in Libertarya had grown to have a population of at least 30,000, and had become the centre of a small Kingdom. In | Considered the end of the Cemsor River Civilisation, the events of the 2,100-1,900 BCE period did not end the usage of Kisin, which survived in a much-diminished output in smaller settlements. Areas connected by trade to the Cemsor valley, most notably western Libertarya, were little-affected by the climatic events in Nizmstan. By middle of the 2nd millenium BCE the city of Padisra in Libertarya had grown to have a population of at least 30,000, and had become the centre of a small Kingdom. In the Farstan region, a large number of towns containing Kalars (fortified stone towers used for grain storage) had sprung up, eventually being united under the town of Great Pesh. In the following centuries several other Kingdoms grew across both Basaqastan and Alta Santia, creating a widely literate interconnected ancient world. | ||

=== Classical Liberto-Ancapistan (6th century BCE – 411 CE)=== | === Classical Liberto-Ancapistan (6th century BCE – 411 CE)=== | ||

In the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, with increasing political and social complexity elsewhere, a resurgence of centralised power occurred in the Cemsor Valley, | In the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, with increasing political and social complexity elsewhere, a resurgence of centralised power occurred in the Cemsor Valley, accompanied by the growth of a new abugida script, [[Nivin script|Nivin]], which was simpler and easier to learn than the older Kisin. Between 500 and 400, the rulers of the city of [[An Alqam]], constructed around the tell-citadel of an ancient Cemsorean town, established rule over the region, proclaiming themselves kings of the 'well-ordered land', or [[Nizmstan]]. Due to its high population density and many urban centres, the kingdom of Nizmstan was quickly established as a major power in the Basaqastan region. | ||

During the 3rd century BCE, three successive Nizmstani monarchs, the queens [[Lom Birin I]], [[Sirimam II]] and king [[Dalizad II]], conquered most of the Basaqastan region, excluding the Farstani kingdom of Great Pesh, establishing the empire of 'Great Nizmstan', which would exert hegemony over western Promeridona. Under Great Nizmstan, regional kings, under central military supervision and often drawing from Nizmstani families, ruled on behalf of the 'Great King' in An Alqam, who presented themself as the appointed delegate of Paleyî, the god of harvest. | |||

During the ascendancy of Great Nizmstan, the Nivim script replaced Kisin as the primary system of writing in Basaqastan, and was modified to create the Santian script outside the Empire's borders. The spoken language of the Cemsor Valley, Classical Basaqese, also supplanted local dialects as an elite language during the period, | During the ascendancy of Great Nizmstan, the Nivim script replaced Kisin as the primary system of writing in Basaqastan, and was modified to create the Santian script outside the Empire's borders. The spoken language of the Cemsor Valley, [[Classical Basaqese language|Classical Basaqese]], also supplanted local dialects as an elite language during the period, creating a common written language across Basaqastan for the remainder of its history, and creating the base for later standardised varieties. The several centuries of Great Nizmstani rule in Basaqastan also facilitated an unprecedented increase in international trade, with goods from as far as eastern Tagrae and Elisia being found in cities and towns alike. | ||

In the early 200s CE, | In the early 200s CE, the ruler of the town of Magario, Piro-Vidama, established rule over much of the Santian uplands, and was chosen as the ruler of the kingdom of Orafars. His successors, Ariaspes and Artainte, would go on to unite Alta Santia under a single ruler. In 240, Artainte was declared 'Lord of all Santia', establishing the beginnings of the Santian Empire. At the time, however, the new Santian state remained in a low position to Great Nizmstan, and in 244 Artainte visited the larger kingdom to join the League of Eshbara, an alliance formed by [[Abdaman III]] of Great Nizmstan to increase Nizmstani influence over Farstan and Santia. | ||

In 285, Basaqastan was shook by the violent eruption of its largest mountain, Mount Birrin. The blast, estimated at VEI 6, caused thousands of immediate deaths and wider climate effects which were far more damaging. Ash blanketed fields across southern Basaqastan, carried by wind, and the mass ejection caused a volcanic winter. These combined to cause an event known as the Long Famine, a famine effecting 3 successive harvests in Basaqastan and causing mass death and peasant rebellion. In 287, a peasant rebellion in the Cemsor Delta seized An Alqam, causing the collapse of central authority and the dissolution of the Great Nizmstanian Empire. In what became known as the Burning Sky Period, newly independent | In 285, Basaqastan was shook by the violent eruption of its largest mountain, Mount Birrin. The blast, estimated at VEI 6, caused thousands of immediate deaths and wider climate effects which were far more damaging. Ash blanketed fields across southern Basaqastan, carried by wind, and the mass ejection caused a volcanic winter. These combined to cause an event known as the Long Famine, a famine effecting 3 successive harvests in Basaqastan and causing mass death and peasant rebellion. In 287, a peasant rebellion in the Cemsor Delta seized An Alqam, causing the collapse of central authority and the dissolution of the Great Nizmstanian Empire. In what became known as the Burning Sky Period, newly independent kings fought over the disintegrating Empire with rapidly shifting areas of control and widespread death. The Long Famine had had a lesser effect on northern Basaqastan and Alta Santia, allowing Farstan and Santia to retain control over their territories. | ||

=== Santian Empire (411 – 1840)=== | === Santian Empire (411 – 1840)=== | ||

In 411, | In 411, king Asher of Santia led an invasion fleet to Farstan. Tension had been building between both states over the northeast coast of Basaqastan, a key area in local trade which Farstan had annexed and placed heavy taxes on. Ashur used a petition by local elites as an excuse to begin the invasion, which ended in a series of military victories and the establishment of Santian control over the centuries-old Emirate. Rather than appoint native leaders to govern its territory as was the Basaqese tradition, Santia appointed members of the Santian nobility to rule the area. This formed the foundation of the Sabania system used in the later Empire. | ||

With the expansion of Santia into Basaqastan it became increasingly tied to the region, both politically and economically. With no central Basaqese power, Santian armies invaded Sagharb in | With the expansion of Santia into Basaqastan it became increasingly tied to the region, both politically and economically. With no central Basaqese power, Santian armies invaded Sagharb in 549 and Exberia (then Uozstan) in 570, appointing Sabani to goven both areas. This expansion continued, with western Ancapistan (then Kimistan) falling in 676. During this period, the Santian capital Orafars became the largest city in the region, with a population of over 200,000. | ||

In | In 702 Santian supremacy over Basaqastan was confirmed with the invasion of the rump kingdom of Nizmstan. With Santian control extended further than ever, the Sabania system was reorganised to better prevent rebellion by placing Aliqi, Sagharb, Basaqastan Hundir and Nizmstan under the control of hereditary Emirs under the suzerainty of Santia. This appeased local elites and prevented rebellion, while keeping Santian administrators in control of more accessible, economically prosperous coastal regions. The last area of Basaqastan outside the fledgling Santian Empire, Libertarya, was gradually intruded on over the following century and had been entirely conquered by 800. | ||

Under the Santian Empire, | Under the Santian Empire, the Santian language gradually replaced classical Basaqese as a lingua franca, but the latter remained the language of the Basaqese elite. Santian elites sent to govern the Sabania brought with them settlers from Santia, which formed communities in most cities and large towns. In 909-930, conflicts between the imperial centre and several social groups in Basaqastan resulted in the breakout of the [[Great Rebellion (Basaqastan)|Great Rebellion]], a revolt in the Cemsor Delta by military garrisons under the control of local elites, which erupted into a long-running military conflict. While initially the kingdom of Nizmstan was revived as an independent state, and almost entirely ended Santian control in Basaqastan, Imperial control was saved by a series of counter-campaigns in the 920s and a large-scale reorganisation of the Santian state. From 930, the Basaqastan region became increasingly integrated into the Santian empire | ||

Following the rebellion, the Santian Empire expanded outside the island of Santia and Basaqastan to become a larger regional power. Post-rebellion developments in imperial ideology increasingly treated the Padisa as a supreme or divinely sponsored ruler, culminating in the reign of [[Giulia the Tamaran]]. The imperial House of Magario became the centre of a complex system of official mythology, adapting to local religious traditions but always claiming divine descent. The use of administrative slaves was also developed. For several hundred years the Empire was able to stamp out local rebellion and remain virtually unchallenged in the Promeridona region. | Following the rebellion, the Santian Empire expanded outside the island of Santia and Basaqastan to become a larger regional power. Post-rebellion developments in imperial ideology increasingly treated the Padisa as a supreme or divinely sponsored ruler, culminating in the reign of [[Giulia the Tamaran]]. The imperial House of Magario became the centre of a complex system of official mythology, adapting to local religious traditions but always claiming divine descent. The use of administrative slaves was also developed. For several hundred years the Empire was able to stamp out local rebellion and remain virtually unchallenged in the Promeridona region. | ||

Revision as of 23:25, 30 July 2023

Federal Republic of Liberto-Ancapistan Komaria Federale a Libertarya-Ancapistan | |

|---|---|

| Motto: "Azadî yan mirin" "Freedom or Death" | |

| Anthem: "Abdanas Lives Again" | |

Location of Liberto-Ancapistan | |

| Capital and largest city | Bajazad |

| Official languages | Basaqese, Santian |

| Recognised regional languages | Fayrean, Mhertag |

| Ethnic groups | Basaqastanians, Santians, Fayreans, Mhertag |

| Demonym(s) | Liberto-Ancapistanian |

| Government | Federal parliamentary republic |

• Chancellor | Rouya Arjmand |

• Vice-Chancellor | Safi Sa |

| Legislature | Parliament |

| House of Asagi | |

| House of Commons | |

| Establishment | |

• Formation of Liberto-Ancapistanian Alliance | 12th April 1944 |

• Unification of Liberto-Ancapistan | 21st March 1955 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,429,736 km2 (552,024 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2025 estimate | 68,845,000 |

• 2018 census | 67,684,853 |

• Density | 48.15/km2 (124.7/sq mi) |

| GDP (PPP) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | 3.9417 trillion Rovas |

• Per capita | 57,255 Rovas |

| GDP (nominal) | 2025 estimate |

• Total | 4 trillion Rovas |

• Per capita | 58,101 Rovas |

| Gini (2025) | 54.1 high |

| HDI (2025) | very high |

| Currency | Fiat (LAF) |

| Time zone | UTC-6 |

| Date format | dd-mm-yyyy |

| Driving side | left |

| Calling code | +87 |

| ISO 3166 code | LTA |

| Internet TLD | .la |

Liberto-Ancapistan (Basaqese: Libertarya-Ancapistan), officially the Federal Republic of Liberto-Ancapistan, is a transcontinental nation spanning southern Evrosia and overseas Autonomous Territories in western Evrosia, Elisia, Antartica and Takaria. Situated primarily across the islands of Promeridona and Santia, it covers an area of 1,429,736 square kilometres (552,024 sq mi) with a population of 68.8 million in 7 constituent Provinces and 3 Autonomous Territories. Liberto-Ancapistan borders the Velika Tzarska Empire, Bekiantum, Hockeyyekcoh and Aether Inc. It is a member of the United Federation of Telrova. Liberto-Ancapistan is a federal parliamentary republic with its capital in Bajazad, the country's largest city and main economic centre; other major urban areas include Sades, Compacipo, Devisgund, Benderand and Orafars.

Etymology

The English name Liberto-Ancapistan is an anglicisation of the Basaqese Libertarya-Ancapistan. This is derived from Liberto-Ancapistan's predecessor, the Liberto-Ancapistanian Alliance (Basaqese: Tifaqa Libertari-Ancapistani), which itself was derived from member states Libertarya and Ancapistan. The former's name was originally a Santian exonym, used to describe the area of Basaqastan outside the Santian Empire - a 'free land'. The latter's name, meaning 'land of the Ancapi' in classical Basaqese (also called classical Nizmstani), refers to the Ancapi, a tribe of the Kimia Culture which existed during the last centuries of the 1st millenium BCE.

History

Prehistory and Ancient Liberto-Ancapistan (before the 6th century BCE)

Archaeological evidence at Lake Mergiri indicates that modern humans have inhabited Promeridona since at least 50,000 BCE. Rock art found in the Res Hills and Sikandin Massif has been dated to 30,000 BCE and 26,000 BCE respectively.

Agriculture first emerged in Liberto-Ancapistan c. 6,500 BCE, around the Cemsor Valley in modern-day Ancapistan Province. The first crops to be domesticated, independently of other areas of agricultural development, were rice and chickpeas. In northern Basaqastan, Promeridonan wheat had been domesticated by 5,000 BCE. The development of agriculture led to the creation of increasingly large settlements. The first walled city in modern-day Liberto-Ancapistan, Rayek, dates to c. 3,500 BCE and was followed in the succeeding centuries by the emergence of several cities around the Cemsor Valley, forming the Cemsor River Civilisation. These walled cities involved stratified social classes and were ruled from at least 2,800 BCE by individual monarchs. During this period, a system of logographic writing, Kisin, developed, initially written only on bones. This was expanded to clay tablets c. 2,600 BCE. The apparent lack of large temple structures and prevalence of oracle-bones suggests that the Cemsor River Civilisation did not involve organised religion, with the localised spirit-worship of later centuries already existing in some form. Around 2,300 BCE, the Cemsor River Civilisation came under the rule of a single king, Akamagoli of the city of Cebar, who established a dynasty which would rule the region for over 150 years.

Between 2,100 and 1,900 BCE most cities in the Cemsor Valley were abandoned, or reduced significantly in size. Most modern archaeological research suggest localised climate change as the primary cause, most significantly a large southward shift in the upper cause of the river, which destroyed centuries-old irrigation networks and deprived cities of access to water and commerce. This course shift was accompanied by a period of increased temperatures, damaging surviving harvests.

Considered the end of the Cemsor River Civilisation, the events of the 2,100-1,900 BCE period did not end the usage of Kisin, which survived in a much-diminished output in smaller settlements. Areas connected by trade to the Cemsor valley, most notably western Libertarya, were little-affected by the climatic events in Nizmstan. By middle of the 2nd millenium BCE the city of Padisra in Libertarya had grown to have a population of at least 30,000, and had become the centre of a small Kingdom. In the Farstan region, a large number of towns containing Kalars (fortified stone towers used for grain storage) had sprung up, eventually being united under the town of Great Pesh. In the following centuries several other Kingdoms grew across both Basaqastan and Alta Santia, creating a widely literate interconnected ancient world.

Classical Liberto-Ancapistan (6th century BCE – 411 CE)

In the 6th and 5th centuries BCE, with increasing political and social complexity elsewhere, a resurgence of centralised power occurred in the Cemsor Valley, accompanied by the growth of a new abugida script, Nivin, which was simpler and easier to learn than the older Kisin. Between 500 and 400, the rulers of the city of An Alqam, constructed around the tell-citadel of an ancient Cemsorean town, established rule over the region, proclaiming themselves kings of the 'well-ordered land', or Nizmstan. Due to its high population density and many urban centres, the kingdom of Nizmstan was quickly established as a major power in the Basaqastan region.

During the 3rd century BCE, three successive Nizmstani monarchs, the queens Lom Birin I, Sirimam II and king Dalizad II, conquered most of the Basaqastan region, excluding the Farstani kingdom of Great Pesh, establishing the empire of 'Great Nizmstan', which would exert hegemony over western Promeridona. Under Great Nizmstan, regional kings, under central military supervision and often drawing from Nizmstani families, ruled on behalf of the 'Great King' in An Alqam, who presented themself as the appointed delegate of Paleyî, the god of harvest.

During the ascendancy of Great Nizmstan, the Nivim script replaced Kisin as the primary system of writing in Basaqastan, and was modified to create the Santian script outside the Empire's borders. The spoken language of the Cemsor Valley, Classical Basaqese, also supplanted local dialects as an elite language during the period, creating a common written language across Basaqastan for the remainder of its history, and creating the base for later standardised varieties. The several centuries of Great Nizmstani rule in Basaqastan also facilitated an unprecedented increase in international trade, with goods from as far as eastern Tagrae and Elisia being found in cities and towns alike.

In the early 200s CE, the ruler of the town of Magario, Piro-Vidama, established rule over much of the Santian uplands, and was chosen as the ruler of the kingdom of Orafars. His successors, Ariaspes and Artainte, would go on to unite Alta Santia under a single ruler. In 240, Artainte was declared 'Lord of all Santia', establishing the beginnings of the Santian Empire. At the time, however, the new Santian state remained in a low position to Great Nizmstan, and in 244 Artainte visited the larger kingdom to join the League of Eshbara, an alliance formed by Abdaman III of Great Nizmstan to increase Nizmstani influence over Farstan and Santia.

In 285, Basaqastan was shook by the violent eruption of its largest mountain, Mount Birrin. The blast, estimated at VEI 6, caused thousands of immediate deaths and wider climate effects which were far more damaging. Ash blanketed fields across southern Basaqastan, carried by wind, and the mass ejection caused a volcanic winter. These combined to cause an event known as the Long Famine, a famine effecting 3 successive harvests in Basaqastan and causing mass death and peasant rebellion. In 287, a peasant rebellion in the Cemsor Delta seized An Alqam, causing the collapse of central authority and the dissolution of the Great Nizmstanian Empire. In what became known as the Burning Sky Period, newly independent kings fought over the disintegrating Empire with rapidly shifting areas of control and widespread death. The Long Famine had had a lesser effect on northern Basaqastan and Alta Santia, allowing Farstan and Santia to retain control over their territories.

Santian Empire (411 – 1840)

In 411, king Asher of Santia led an invasion fleet to Farstan. Tension had been building between both states over the northeast coast of Basaqastan, a key area in local trade which Farstan had annexed and placed heavy taxes on. Ashur used a petition by local elites as an excuse to begin the invasion, which ended in a series of military victories and the establishment of Santian control over the centuries-old Emirate. Rather than appoint native leaders to govern its territory as was the Basaqese tradition, Santia appointed members of the Santian nobility to rule the area. This formed the foundation of the Sabania system used in the later Empire.

With the expansion of Santia into Basaqastan it became increasingly tied to the region, both politically and economically. With no central Basaqese power, Santian armies invaded Sagharb in 549 and Exberia (then Uozstan) in 570, appointing Sabani to goven both areas. This expansion continued, with western Ancapistan (then Kimistan) falling in 676. During this period, the Santian capital Orafars became the largest city in the region, with a population of over 200,000.

In 702 Santian supremacy over Basaqastan was confirmed with the invasion of the rump kingdom of Nizmstan. With Santian control extended further than ever, the Sabania system was reorganised to better prevent rebellion by placing Aliqi, Sagharb, Basaqastan Hundir and Nizmstan under the control of hereditary Emirs under the suzerainty of Santia. This appeased local elites and prevented rebellion, while keeping Santian administrators in control of more accessible, economically prosperous coastal regions. The last area of Basaqastan outside the fledgling Santian Empire, Libertarya, was gradually intruded on over the following century and had been entirely conquered by 800.

Under the Santian Empire, the Santian language gradually replaced classical Basaqese as a lingua franca, but the latter remained the language of the Basaqese elite. Santian elites sent to govern the Sabania brought with them settlers from Santia, which formed communities in most cities and large towns. In 909-930, conflicts between the imperial centre and several social groups in Basaqastan resulted in the breakout of the Great Rebellion, a revolt in the Cemsor Delta by military garrisons under the control of local elites, which erupted into a long-running military conflict. While initially the kingdom of Nizmstan was revived as an independent state, and almost entirely ended Santian control in Basaqastan, Imperial control was saved by a series of counter-campaigns in the 920s and a large-scale reorganisation of the Santian state. From 930, the Basaqastan region became increasingly integrated into the Santian empire

Following the rebellion, the Santian Empire expanded outside the island of Santia and Basaqastan to become a larger regional power. Post-rebellion developments in imperial ideology increasingly treated the Padisa as a supreme or divinely sponsored ruler, culminating in the reign of Giulia the Tamaran. The imperial House of Magario became the centre of a complex system of official mythology, adapting to local religious traditions but always claiming divine descent. The use of administrative slaves was also developed. For several hundred years the Empire was able to stamp out local rebellion and remain virtually unchallenged in the Promeridona region.

Through the 1400s and 1500s, Basaqese individuals gained new prominence with the growth of slavery and piracy. New navigation techniques made long-range voyages easier, and raiding in the Tamaran and Acadian oceans made slaves cheaper and more accessible. Over time these practices, which were sponsored by the Santian state, were centralised in the control of a small number of Basaqese captains, who commanded fleets challenging the Imperial Navy. In the 1580s the growth of these captains, who became known as Sea-Beys, caused difficulty for the Empire over increasingly disruptive piracy affecting not only foreign but also Santian trade. Fleeing Santian disruption, many established control overseas, and were followed by a newly founded imperial navy. The most prominent of these was the Beylik of Fayre in the Elisian Fayre Islands, which was conquered by Santia in 1608 after over a decade of existence.

In the 1700s and 1800s, Santian power was challenged by emerging colonial and industrial powers. The Empire's borders began to contract and imperial power was hampered by growing scepticism of the Padisa's supremacy and Santia's political system. In the 1820s and 1830s this took the form of the Liberal Society, an underground republican group which sought to establish an elected Parliament and limits on imperial authority. The power of the Liberal Society was weakened and co-opted after the 1833 Green Revolution, a period of intense rioting and disruption led by the Liberals, which saw Padisa Vittorio IV abdicate in favour of his son, Ferando XII. Ferando instituted reformist policies, including the creation of a weak parliament, but did so only when it was necessary to re-entrench imperial power. A radical Basaqese faction of the Liberal Society, nicknamed the 'Libertarians' due to the geographic origin of much of their leadership, was dissatisfied with changes and after the Santian Empire saw several overseas rebellions rose up itself. This began the Summer Revolution, which saw a combination of Libertarian revolutionaries, peasant rebels and anti-reformist elements break southern Basaqastan away from the Empire in the form of the Republic of Libertarya and Confederation of Ancapistan.

Pre-Unification (1840 – 1955)

Despite the reforms of Ferando XII, liberal sentiment began to become more radical, augmented by the economic pressures caused by a new flow of cheap goods from newly industrised countries to Santia. This encouraged growing nationalism and rebellious feeling in the territories of the Santian Empire, and by the middle of the 1860s, several territories - including northern Basaqastan - faced large-scale revolts. The Santian Army was reformed and expanded to counter threats, leaving the Empire's finances in a poor state, and precipitating harsh increases in taxation. These pressures culminated in the 1872 Tricolour Revolution, led by liberals, radicals and proto-socialists, which saw the abdication of Ferando XII and establishment of a Republic. The revolution triggered the rapid disintegration of the Empire, which had largely ceased to exist despite the efforts of rogue generals by 1876.

The new states in southern Basaqastan, Libertarya and Ancapistan, both pioneered liberal approaches to government. Libertarya, under the newly organised Libertarian Party, developed a centralised but restricted state with a codified constitution and parliamentary system, inspired by foreign democracies. Ancapistan was the product of compromise between the Emir of Nizmstan, local officials and the peasant armies of Sayab Etyio, becoming a less coherent collection of hereditary territories and autonomous cities with only a weak central government. Both states, seeking to de-Santianise, elected to adopt the foreign latin alphabet rather than revive the now-dead Nivin.

The retreating Santia retained only a small strip of Santian-settled land known as the Varisil Strip in northern Basaqastan. Outside this area, Libertarya-inspired revolutionaries established the Republic of Farstan, while central Basaqastan solidified into an eclectic federation, the Union of Basaqastan.

The liberal Summer Revolution had attracted significant foreign interest. Hector Rand, a west Evrosian industrialist, had helped to fund the Ancapistanian portion of the revolution and in 1845 set up a company town named Benderand. Both Ancapistan and Libertarya invited large numbers of migrants from overseas, promising freedom for minorities and economic opportunities. In the 1890s, limited industrialisation began to occur in Libertarya, Ancapistan and Santia, encouraged by all three states. In Libertarya the resulting social change caused a political deadlock, eventually resulting in an insurgency in the northern city of Exber in 1901 - the first conflict in the region since the abandonment of northern Basaqastan. The Exberian rebels were successful when the Union of Basaqastan admitted Exber as a federal subject, prompting Libertarya to release the city. Following the humiliation of the rebellion, Libertarya elected a new government and formed a standing army as well as basic welfare state. In Santia, industrialisation saw a growing socialist movement which was cracked down on by Gian Pico, a member of the Council of State who established a dictatorship between 1909 and his 1923 assassination.

Through the 1930s and 1940s political currents in Basaqastan and Santia put both regions on opposing paths. In the former, calls for unification to oppose foreign intervention picked up, spearheaded by the Union of Basaqastan. The Union entered talks with the government of Ancapistan, but these fell through after the 1941 assassination of foreign minister Omar Fitzrouth. This prompted Ancapistan to propose an economic and military union with the Republic of Libertarya, which formed as the Liberto-Ancapistanian Alliance in 1944 and formed the basis for modern Liberto-Ancapistan. In Santia, a brief period of democratic after the death of Gian Pico receded and the consolidation of Basaqastan was met with fear of the Varisil Strip's invasion. Through the 1940s a general, Urban Maasino, spearheaded the politicisation of the military and introduced a foreign-inspired form of Santian fascism which posited that security could only be ensured for Santia with massive population growth.

After rising tension, remilitarisation and the elevation of Maasino to a de-facto head of government in Santia, the country invaded northern Basaqastan in 1950, the beginning of the Great Santian War. Initially, the small and less industrial states of the north were quickly taken under Santian rule with few casualties. Further south, however, the Santians met opposition in the Union of Basaqastan, and the 1952-1953 Battle of Exber resulted in large-scale and atrocities. Hundreds of thouands of troops were involved on both sides and the city, partially evacuated, was almost entirely destroyed. While the Santians eventually emerged from the battle victorious, their war effort was slowed and the Liberto-Ancapistanian Alliance had militarised to a great enough extent to resist the following invasion. The Liberto-Ancapistanian forces would begin to push back, and was emboldened when the Union of Basaqastan agreed to become a member state. In 1954 the Liberto-Ancapistanian Alliance purchased a single atomic bomb from overseas, which was stolen while in transit and later dropped on the Santian command centre in Varisil under mysterious circumstances. The Santian military, already battered by years of war, quickly collapsed and in 1955 the war was ended with an unconditional surrender in the Varisil Accord. Santia was demilitarised, the Varisil Strip and Mherta were annexed, and the Liberto-Ancapistanian Alliance shortly afterwards united into Liberto-Ancapistan; a federal state with a central government based on the Libertarian model. Shortly afterwards, members of the Santian Assembly conducted a soft coup and expelled military or nationalist elements from the government, going on to liberalise the country in the 'Silent Revolution'.

Post-Unification (1955 – present)

Post-unification Liberto-Ancapistan was decentralised but nevertheless dominated by Libertarya and the wider south. In the 1955 general election which decided on the new country's first government, the ever-powerful Libertarian Party successfully exported itself to new territories and its leader, the former Chancellor of Libertarya Alexandre Delon, became the first Chancellor of Liberto-Ancapistan. Delon's tenure, which lasted until 1971, was marked by a free, but heavily regulated, economy, and military spending that remained high even after the Santian threat had subsided. His government aggressively pushed Basaqese nationalism, but also opened Liberto-Ancapistan's borders to unrestricted immigration. After reconstruction had largely concluded in the early 1960s, Liberto-Ancapistan experienced a sustained period of economic growth, known as the great leap or Basaqese economic miracle. This transformed the largely rural country into a developed industrial economy, where industrial capitalism had previously been limited to parts of southern Basaqastan, and had an especially significant impact on the inland provinces of Basaqastan Hundir and Rojava-Navenda. Between the late 1950s and mid 1960s, Santia's war-battered economy entered into a long, sustained depression; a period which would come to be known as the 'lost decade'.

During the 1960s, the Delon government pursued an assertive, but officially neutral, foreign policy, which included the development of a small home-built nuclear arsenal. In 1962, Delon accepted a proposal by industrialist Harlan Rand which would see a board of industrialists, headed by Rand himself, take control of the Region of Mherta and construct a large planned city, subject to few regulations, within Liberto-Ancapistan. This territory was first called the 'New Industrial City', but was later renamed to Compacipo.

In 1970, after a brief period of recovery, the Santian economy collapsed for a second time. As a result of the crisis, the Santian government petitioned to join Liberto-Ancapistan as a Province with special powers; something which had been often speculated on in previous years. Because of the favourability of the deal to both nations, with Santia gaining access to a strong government and market, and Liberto-Ancapistan absorbing its largest threat, the cabinet of Liberto-Ancapistan quickly pushed for Delon to accept it. The Chancellor refused, as he had remained distrustful of Santia since the war. Responding to Delon's rejection, the Libertarian Party cabinet forced Delon to resign and elected Sujitra Taksin in his place. Taksin opened negotiations for the plans and Santia joined Liberto-Ancapistan in November 1971.

The second Chancellor of Liberto-Ancapistan, Sujitra Taksin, presided over political turmoil and an economic slowdown. Taksin's Liberto-Ancapistan played down the nationalism of the Delon government and provided greater autonomy to the Provinces, while full embracing a neutral foreign policy. This moderation of policy was in part brought about by a series of coalition or minority governments, which often broke down. In 1977 Liberto-Ancapistan's economy underwent a recession, the so-called Corners Crisis, and the Libertarian Party's coalition partners abandoned Taksin to form their own, more left-wing alternative coalition, forming the first non-Libertarian government in Liberto-Ancapistanian history. Led by independent MP Ashna Ali, the coalition took measures to end the crisis with only limited success, surviving the 1978 election but being forced out two years later by a reformed Libertarian Party under Sherin Mezaros.

Sherin Mezaros, at only 33 years old, became the youngest Chancellor in Liberto-Ancapistanian history. The Corners Crisis was framed as the effect of overregulation, a lack of central banking control and a large public sector, allowing Mezaros to frame his government as a solution rather than as a continuation of the one which had began it. In power, Mezaros significantly downsized the Liberto-Ancapistanian military, deregulated the economy, decreased the autonomy of Provinces and restricted the ability to print money - which had previously been spread across several local banks - in the hands of the central Basaqastan National Bank. Mezaros' newly deregulated economy would result in increasing deindustrialisation and unemployment, but gave way to greater growth. By the late 1980s, however, the Chancellor's brazen leadership style led to several high-profile resignations and in 1990 he was forced out in favour of billionaire backer Henry Rand. Only 9 months later, in the 1990 election, the Libertarian Party once again lost its majority and was prevented from forming a government by a coalition, under the Liberal-Radical Party's Zakia Askari. However, Rand remained Libertarian leader.

Under the leadership of Zakia Askari, Liberto-Ancapistan continued to maintain the reforms of Sherin Mezaros, as the governing coalition was too divided to make any major shifts in policy. However, there were limited moves to once again restore the autonomy of the provinces to something near their pre-Mezaros levels. The Liberal-Radical-led coalition was able to survive the 1992 election, but after a number of high-profile splits and ministerial resignations, in 1994 the Libertarian Party of Henry Rand was able to regain its majority and form a government.

During his second term, Henry Rand continued Mezaros' broadly right-wing policy but was more pragmatic and introduced some regulations after a spate of industrial disasters. His largely unremarkable Chancellorship was also marked by the introduction of nuclear submarines, giving Liberto-Ancapistan a professional nuclear deterrant force for the first time. In 1999, a spate of scandals emerged involving allegations of serious corruption across the Rand government. This intensified to the point where a vote of no confidence was successful, and Rand called an election in early 2000. There, he was defeated decisively by a merger of smaller local parties following a more dogmatic, principled libertarianism; the Minarchist Coalition under Ameus Grey.

Ameus Grey took power with a large majority in 2000 and passed a constitutional amendment aimed to reduce corruption and partisanship by replacing the Chancellor with the Executive Council, composed of the leader of the largest political party in the House of Commons (the tiebreaking President of the Council), the leader of the second largest political party in the House of Commons, the speakers of both Houses of Parliament and a fifth Councillor directly elected every 8 years for single terms. This new government structure saw greater indecision but moderated the more radical Minarchist policies of Grey. By the mid 2000s, the Minarchist Coalition's dominance gave way to a more multi-party political system. The Minarchist government became more right-wing as Grey's leadership position was entrenched and in the late 2010s a large anti-austerity protest movement gathered hundreds of thousands across several Liberto-Ancapistanian cities. After directly elected Executive Councillor Andreas Capelle was arrested for embezzlement, Grey lost the 2020 election to centre-left party Progress.

Progress' leader, Casimir Bergen, restored the Chancellorship in a 'constitutional coalition' with a resurgent Libertarian Party. He moved away from austerity measures and returned to a regulated economy, still largely private but with a stronger public sector and universal basic income. In 2023, Alta Santia Province unilaterally declared autonomous status as leverage in an attempt to gain more autonomy. In 2025, the crisis was resolved with the granting of new powers in the Orafars Agreement.

Following the 2026 Liberto-Ancapistanian general election, Bergen was succeeded as chancellor by Rouya Arjmand of the Libertarian Party.

Geography

Liberto-Ancapistan is the third-largest country in Evrosia; bordering the Velika Tzarska Empire, Bekiantum, Hockeyyekcoh and Aether Inc. Liberto-Ancapistan is also bordered by the Acadian Ocean to the south and Tamaran Sea to the east, and straddles the Devisgund Strait. Liberto-Ancapistanian territory covers 1,429,736 square kilometres (552,024 sq mi) of land.

Elevation ranges from the Ciona mountains in the west and Santian mountains in the north (highest point: Mount Birrin at 5,607 metres), to the endorheric Qûmêşîn basin (lowest point: Lake Mergiri at 13 metres below sea level). The Qûmêşîn basin is dominated by a large desert, the Qûmêşîn desert, which covers most of east-central Liberto-Ancapistan. Southern Liberto-Ancapistan is traversed by several major rivers, including the Cemsor and Diliyen. Significant natural resources include iron ore, coal, oil, salt, potash, and lithium.

Climate

Liberto-Ancapistan has a varied climate, including mediterranean, arid, and continental climate regions. Winters range from mild in the south to cold in the uplands, and are generally rainy. Summers are generally hot and dry, reaching extreme temperatures in the Qûmêşîn desert. The southern Provinces have prevailing winds that bring in moist air from the Acadian Ocean, moderating temperatures and bringing increased precipitation. Conversely, the northern Provinces see more extreme temperatures.

Average daily highs in summer reach 32°C in the southern Provinces, and 35°C in the northern Provinces, with average daily lows in winter reaching 10°C and 2°C respectively. The highest temperature ever recorded in Liberto-Ancapistan was 48°C in 2008, at Lake Mergiri in Basaqastan Hundir Province. The lowest temperature recorded was -11°C, at Gias in Alta Santia Province.

Biodiversity

Liberto-Ancapistan is home to a diverse array of animal and plant species, dispersed across seven terrestrial ecoregions. The southern Provinces, constituting the Western Promeridona conifer-broadleaf forests and Promeridona coniferous forests bioregions, contain the majority of Liberto-Ancapistanian biodiversity. Vegetation is varied and ranges from forests, to shrublands, to grasslands. Sclerophyll trees such as the Nizmstan Oak, as well as conifers such as the Nizmstani Cypress, constitute the majority of trees in forests. Natural fires are not uncommon and most native species are adapted to lessen or exploit their effects. Wild animals include fallow deer, Santian tigers, lions, grey wolves, onagers, wild sheep, goats and tortoises. Domestic animals consist primarily of sheep, goats and cattle.

Liberto-Ancapistan contains 17 nationally protected National Parks, including the Cemsor Delta National Park, Mount Birrin National Park, Sikandin Massif National Park and West Santian Mountains National Park. In addition, there are over 70 Notable Scenic Areas on a Provincial level, which provide substantial environmental protections.

Politics

Liberto-Ancapistan is a federal, parliamentary, representative democratic republic. National (federal) legislative power is vested in the Parliament of Liberto-Ancapistan, consisting of the House of Commons and House of Asagi. The House of Commons is elected in 500 single-member constituencies using the first-past-the-post system, while the House of Asagi is elected in 29 multi-member constituencies using the single transferable vote system. The Liberto-Ancapistanian political system operates under a framework set out in the 1955 constitution of Liberto-Ancapistan, known as the National Constitution. Amendments require a 2/3 absolute majority in both Houses of Parliament, taking into account all members rather than those present.

The head of state of Liberto-Ancapistan is constitutionally defined as the collective of both Houses of Parliament, constituting 610 distinct individuals. This is practically expressed through the non-partisan speakers of both Houses, who are elected by each on a simple majority and are otherwise responsible for the overseeing of daily sessions. Both are obligated to sign all bills before they become law, but do not have the ability to refuse. The head of government of Liberto-Ancapistan is the Chancellor, elected by the House of Commons on a secret ballot; elections are managed by the Speaker of the House of Commons, and usually occur after an election only when a governing coalition has been formed. The Chancellor excercises executive power through a cabinet.

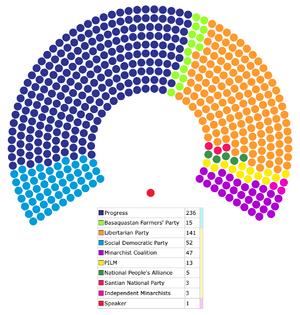

Between 1955 and 2000, Liberto-Ancapistanian politics were dominated by the Libertarian Party (though this was briefly disrupted twice), and between 2000 and 2020 the Minarchist Coalition within a multi-party system. Since 2020, Liberto-Ancapistan has formed a two-party system between Progress and the Libertarian Party. Every Chancellor except the independent Ashna Ali has been from these three parties, though the Social Democratic Party and Basaqastan Farmers' Party have been the junior partners in coalition governments, and there has not been a non-coalition majority government since 2004. Other parliamentary parties include the Party of Independent Liberals and Minarchists, National People's Alliance, Santian National Party, and United Left.

Federal Subjects

Liberto-Ancapistan is a federal state composed of seven constituent Provinces and three Autonomous Territories, all of which are overseas. Each federal subject has the right to determine internal subdivisions, which are called Districts in most Province but are also referred to as Beyliks in Alta Santia and Quarters in Bajazad. Federal subjects further have the right to determine the structure of their governments, though within a strictly democratic structure. All Provinces but Rojava-Navenda maintain a unicameral legislature, called an Assembly, and a parliamentary government system. The Fayre Islands Autonomous Region and Compacipo Autonomous Region have unicameral Assemblies and City Councils, respectively. The third Autonomous Region, the Liberto-Ancapistan Antartic Region, has a seven-person Executive Council which functions both as a legislature and executive. The powers allocated to Provinces varies, with Alta Santia having greater autonomy than the remaining six, while the powers of Autonomous Territories varies significantly.

| Federal Subject | Status | Capital City | Land Area (km2) | Population | Head of Government |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Province | Sades | 99,459 | 16,836,000 | N/A | |

| Province | Benderand | 159,274 | 12,232,000 | Marie Marson | |

| Province | Orafars | 105,930 | 12,115,000 | Petra Farago | |

| Province | Bajazad | 2,408 | 8,815,000 | Hariq He | |

| Province | Capitoli | 89,829 | 8,272,000 | Ilena Valogli | |

| Province | Exber | 140,885 | 4,445,000 | Artanto Uzunken | |

| Province | Berqualin | 145,625 | 3,685,000 | Miran Lapache | |

| Autonomous Region | Compacipo | 10,533 | 2,136,000 | Zarin Gulixan | |

| Autonomous Region | Port Ramstad | 38,325 | 298,000 | Stefan Lindbergh | |

| Autonomous Region | N/A | 150,263 | 500 | N/A |

Law

The seven provinces of Liberto-Ancapistan has a civil war system based on the legal system of predecessor state Libertarya, originating in ancient Nizmstani law. The only federal subject which deviates from this model is the Fayre Islands Autonomous Region, which incorporates aspects of customary law. The Dibiha Destûrî ya Bilind (High Constitutional Court) is the country's supreme court, concerned primarily with judicial review. It may strike down parliamentary legilation found to be unconstitutional, and is selected by an independent legal commission.

National-level Criminal and civil law are codified in a single, two-part code; the Qanum Mezin (Great Law), of which provincial versions exist incorporating local laws. The Liberto-Ancapistanian legal system is concerned primarily with rehabilitation and public protection, with no existing death penalty and imprisonment without eligibility of parole lasting for no more than ten years. Petty crimes are charged by a single professional judge, while other crimes are charged by a panel of two professional judges and three lay judges. Prisons and courts are managed on a national, rather than provincial, level; however, each Province has it's own court of appeal concerned with Province-level law, subordinate to the High Constitutional Court.

Foreign Relations

Liberto-Ancapistan has an extensive diplomatic network, holding relations with more than 140 countries. Liberto-Ancapistan is a member of the United Federation of Telrova (UFT) since 2022, playing a pivotal role in the organisation's development and provided two Secretary-Generals, serving for a longer combined tenure than Secretary-Generals from any other nation. It is also a founding member of the Group of Nations (GN), and observer state of the Nordesian Union (NU). Since abandoning the long-held 'neutrality clause' in 2014, Liberto-Ancapistan has promoted a strong, but multilateral, UFT operating within a framework of international law. It has maintained close relations with the Fleet of Oceans and Fendiralia, a country which it championed the continued existance of in the aftermath to the Two Day War.

Liberto-Ancapistanian foreign policy is global in character and has sometimes been characterised as independent-minded or uniltateralist, contrasting with its status as a member of the UFT. It was a key promoter of the Two Day War against Fendiralia, but has since disavowed the outcomes of the conflict. Liberto-Ancapistan has been criticised for it's low spending on international aid when compared to similar nations.

Liberto-Ancapistan's trade policy focuses on maximising international trade, with tariffs and other trade barriers only rarely being present outside the agricultural sector. Economic sanctions by the country are only very rarely used, with the most notable case of sanctions being the 2022-present embargo against rival Rex Omnia in the aftermath of the country's invasion of Charville.

Military

Liberto-Ancapistan's military, the Liberto-Ancapistan Self-Defence Force (LASDF), is organised into the Liberto-Ancapistan Ground Self-Defence Force (LAGSDF), Liberto-Ancapistan Maritime Self-Defence Force (LAMSDF), and Liberto-Ancapistan Air Self-Defence Force (LAASDF). In 2024, military expenditure was at F168 billion (84 billion Rovas), about 2.1% of the country's GDP.

As of 2024, the LASDF has a strength of 202,100 active personnel, as well as over 100,000 reservists. The LASDF is composed entirely of volunteers, and all roles are gender-neutral. In peacetime, the LASDF is commanded by the Secretary of Defence, while in wartime this duty is transferred to the Chancellor. The Liberto-Ancapistanian constitution states that the LASDF is defensive in purpose, however this has had no actual legal ramifications, and the country has engaged in several military operations unrelated to the territorial integrity of Liberto-Ancapistan. The LASDF maintains an expeditionary force of 1,500 in Fendiralia and 300 in Rova Port (the multinational headquarters of the UFT).

Economy

Liberto-Ancapistan has a partially regulated market economy, which is the fourth-largest in the UFT. The Ministry of Finance, led by the Finance Secretary, has responsibility for executing government financial and economic policy. The National Basaqastan Bank (NBB) is Liberto-Ancapistan's central bank and has sole right to issue notes and coins in the country's currency, the Fiat. The Rova, issued by various banks across the UFT, is also officially legal tender. Since 1979, the NBB has had the authority to set interest rates according to it's own inflation target, and Presidents of the bank are selected by an independent commission.

The Liberto-Ancapistanian economy is predominantly located in the services sector, which make up 57% of GDP, but also retains a large industrial component in comparison to similar high-income countries, contributing 42% of GDP. Agriculture represents 1% of GDP. Bajazad is a major financial centre in southern Evrosia, while Devisgund is a major port and the Compacipo Autonomous Region a major centre of high-skill manufacturing, including automobile production and shipbuilding. As a member of the UFT, Liberto-Ancapistan is part of the organisation's expansive free trade area, covering 17 nations.

The economy of Liberto-Ancapistan was primarily agricultural until the early 20th century, during which it underwent a sustained period of industrialisation, though only reaching a level of industrialisation seen in other high-income nations in the late 1950s. Southern Liberto-Ancapistan was historically a major regional centre of coal mining, and today the country has a burgeoning lithium mining industry which has experienced rapid growth through the 2020s. While de-industrialisation has taken place in Liberto-Ancapistan, this has occured to a lesser extent than most other major industrial countries.

Liberto-Ancapistan is home to several major industrial, medical and telecommunications companies. Most notably, RandCorp is the world's largest industrial conglomerates, with an annual revenue of over 400 Billion Rovas as of 2024. Harrison Rand, the company's majority shareholder, is Telrova's richest person as of 2025, and the Rand Family the world's richest family, with a combined wealth of over 330 Billion Rovas. The Liberto-Ancapistanian economy has been criticised for it's large focus on large conglomerates, with a lower proportion of the economy being made up of small or medium enterprises and startups than similar nations.

Infrastructure

Transport in Liberto-Ancapistan is serviced by an expansive system of motorways and railways. The country's railways are owned by the publicly owned Liberto-Ancapistan Interways (LAI), while rolling stock is privately operated on heavily regulated contracts with LAI. The country's high-speed railway network consists of three lines, which see trains travel at speeds of up to 320 km/h. Liberto-Ancapistan's largest airport is Bajazad Airport. The Port of Devisgund is one of the top fifteen largest container ports on Telrova.

75% of Liberto-Ancapistanian energy is generated by nuclear power stations, controlled by the publicly owned Basaqastan Nuclear Board (BNB). Since 2000, Liberto-Ancapistan has began to replace outdated power stations with lower-cost renewable energy sources such as wind, which contribute 15% of energy. The remaining 10% of energy, concentrated in Alta Santia Province (which became part of Liberto-Ancapistan after initial nuclearisation), is provided primarily by private coal-fired power stations. Liberto-Ancapistan has passed several acts aiming to reduce greenhouse gas emmissions, as well as decrease descruction to natural environments by industrial exploitation. This includes a commitment to become carbon neutral by 2045, in line with UFT targets.

Demographics

Liberto-Ancapistan has a population of 67.7 million according to the 2018 Liberto-Ancapistanian census, rising to 68.8 million as of 2025. Its population density stands at 47.48 inhabitants per square kilometre (122.97 per square mile). The overall life expectancy in Liberto-Ancapistan at birth is 82.8 years (80.7 for men and 84.7 for women). The fertility rate is 1.99 children born per woman.

Liberto-Ancapistan was historically one of the world's most popular immigration destinations, and in the 2010s and 2020s has seen increased international immigration after years of slowdown. The majority of migrants live in urban areas in the south and northeast, as well as the Compacipo Autonomous Region. Of the country's residents, 28.6 million people (42.2%) were of immigrant or partially immigrant descent as of 2018. 4.6 million residents (6.7% of the population) were born outside of Liberto-Ancapistan as of 2018.

Liberto-Ancapistan has a number of large cities. Cities are designated on a Provincial level, and typically consist of either a single city-district with special adminstrative powers or a multi-district Combined Authority. The largest city in Liberto-Ancapistan is Bajazad, which covers the entirity of its metropolitan area.

Largest cities in Liberto-Ancapistan

2025 Estimate | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Rank | Province/Region | Pop. | Rank | Province/Region | Pop. | ||||

| 1 | Bajazad | Bajazad | 8,815,000 | 11 | Luqiu | Libertarya | 466,000 | ||

| 2 | Sades | Libertarya | 2,582,000 | 12 | Berqualin | Basaqastan Hundir | 449,000 | ||

| 3 | Compacipo | Compacipo | 2,136,000 | 13 | Maritere | Peravên Far | 410,000 | ||

| 4 | Devisgund | Peravên Far | 1,655,000 | 14 | Pescalsi | Alta Santia | 387,000 | ||

| 5 | Benderand | Ancapistan | 1,195,000 | 15 | An Alqam | Ancapistan | 385,000 | ||

| 6 | Orafars | Alta Santia | 1,043,000 | 16 | Silosovia | Libertarya | 349,000 | ||

| 7 | Tabariere | Ancapistan | 873,000 | 17 | Etarif | Ancapistan | 332,000 | ||

| 8 | Marsal | Alta Santia | 871,000 | 18 | Bajazad li Parir | Ancapistan | 306,000 | ||

| 9 | Capitoli | Peravên Far | 651,000 | 19 | Navenurt | Rojava-Navenda | 284,000 | ||

| 10 | Exber | Rojava-Navenda | 510,000 | 20 | Selitos | Libertarya | 276,000 | ||

Ethnic Groups

The Provinces of Liberto-Ancapistan are dominated by two major ethnic groups, Basaqastanians and Santians. Basaqastanians are the majority in all Provinces except Alta Santia (forming the historical region of Basaqastan), as well as the Autonomous Region of Compacipo. According to the 2018 census, Basaqastanians comprise of 63% of the total population. Most Basaqastanians natively speak the Basaqese language. Santians are the majority ethnic group in Alta Santia Province, and have a significant presence in several other Provinces: most notably Peravên Far, which includes the majority-Santian 'Varisil Strip' region. Overall, Santians comprise 27% of the total population. Most Santians in Alta Santia and Peravên Far natively speak the Santian language, while those in other Provinces typically speak the Basaqese language.

Liberto-Ancapistan is also home to several other ethnic groups. The native inhabitants of the Compacipo Autonomous Region, the Mhertag, form around 21% of the population, while in the Fayre Islands Autonomous Region 75% of the population belongs to a Nordesian ethnic group, the Fayreans. In addition to native minority groups, there exist several large immigrant population groups. The Qiren form around 5% of the total population, and originate from various nations in Elisia; most are concentrated in Bajazad Province and Libertarya Province, with the former's Rohilat Quarter having a Qiren plurality population. Narushians, originating from Oktadonia, the Great Austronisian Empire and Socialist Platypus, have provided many important figures in Liberto-Ancapistanian history and make up 3% of the total population. Liberto-Ancapistan is also home to a variety of smaller immigrant groups, including Braitians, Fendiralians, Lyonians and Malidians.

Languages

The two official languages of Liberto-Ancapistan are Basaqese and Santian, which are officially co-equal, and National-level documents must be provided in both. However, Basaqese is the de-facto language of government and foreign relations. Basaqese is spoken by approximately 95% of the population, of which about 45% are monolingual. Santian is spoken by 40% of the population, of which around 4% are monolingual. The third most popular language in Liberto-Ancapistan, according to the 2018 census, is Qiren, spoken by 3% of the total population, with other immigrant communities also often retainng their 'native' languages. In addition to Basaqese and Santian, two native regional varieties are recognised; Fayrean and Mhertag, both of which are spoken in an associated autonomous region..

Each Province and Autonomous Region has the right to declare its own official language, to be used in public information, road signs, and safety-related regulations. The Provinces of Libertarya, Ancapistan, Bajazad, Rojava-Navenda and Basaqastan Hundir maintain Basaqese as their sole official language, as does the Liberto-Ancapistan Antartic Region. The Province of Alta Santia maintains Santian as its sole official language, while in Peravên Far Province, both Basaqese and Santian have co-official status. The Compacipo Autonomous Region maintains Basaqese and Mhertag as co-official languages. The Fayre Islands Autonomous Region is the only internal unit of Liberto-Ancapistan to not have a national official language as one of its provincial official languages, instead using only the Fayrean language.

Religion

According to the 2018 census, the largest religion in Liberto-Ancapistan is Bowism, with 52% of the population identifying as Bowist. As a non-organised religion, internal variations within Bowism are difficult to measure, however most studies indicate that the most popular variety of Bowism is Kevirozian Bowism, followed by Pluralist and then Alanchian Bowism; all are strongly region-associated. The second largest religion in Liberto-Ancapistan is Santian Folk Religion, self-identified as by 18% of the population. Both religions are indigenous to Liberto-Ancapistan.

The third-largest religion in Liberto-Ancapistan is christianity, followed by approximately 17% of the population. Traditionally the christian community has been divided between 'Nivin Christians', who adopted the faith during the existence of the Santian Empire, and 'Revised Christians', who adopted the faith or migrated to Liberto-Ancapistan after the end of the Santian Empire. The population difference between both groups is unknown, as Liberto-Ancapistanian census categories do not distinguish between different forms of christianity and even associated faiths, including Materism and Lyonism. Only around 9% of the population of Liberto-Ancapistanians identify as irreligious, a significantly smaller proportion than other developed countries. However, the number of people who do not believe in a higher power or the supernatural is similar, with many identifying as Bowist or Santian Folk for their cultural implications.

Education

Educational policy in Liberto-Ancapistan is largely delegated to individual provinces. Across Liberto-Ancapistan, school attendance is compulsory between the ages of 5 and 16. Primary schooling usually occurs along a single-unified track, while secondary schooling splits along two separate curriculums based on whether academic or vocational education is pursued. Apprenticeships are common and most medium-sized or large companies have agreements with vocational school associations. Liberto-Ancapistanian schooling is not divided based on academic achievement until the end of compulsory education at 16, with all students being admitted to earlier schools regardless of qualification. Most schools in Liberto-Ancapistan are state-operated, though traditional state-contracted Dibiha Schools (which cater to both primary and secondary education) and fee-paying private schools exist in most Provinces.

Most Liberto-Ancapistanian universities are public institutions operated on a national level. All are fee-paying, but with several conditions to ensure that expenses are not incurred on former students who do not make the medium income. The oldest, the Orafars Imperial Dibiha, dates to the 1200s CE. The University of Silosovia in Libertarya Province is considered to be the most prestigious university in Liberto-Ancapistan, and according to the World University Survey is in the top 15 most prestigious universities globally.

Health

Liberto-Ancapistan maintains a national universal healthcare system, which originates in the healthcare system of the Republic of Libertarya established in 1909. All individuals are covered by a state-subsidised public health insurance, but may elect to instead choose a private insurance plan. According to the Ministry of Health, over 75% of the Liberto-Ancapistanian healthcare system is publicly funded.

Culture

Culture in Liberto-Ancapistan has been historically influenced by cultural currents originating in different parts of the Santian Empire, reaching into southern mainland Evrosia, east into eastern Promeridona, and west into the South Evrosian Archipelago. Since the end of the Empire, this influence extended to industrial foreign nations. Liberto-Ancapistan is known for its varied folklore and local festivals, many of which have survived into the 21st century due to the relatively recent unification and industrialisation of the country.

Historically Liberto-Ancapistan used the Ashuran Calendar, a twelve-month solar calendar which placed the division between years at the spring equinox. While Liberto-Ancapistan has used the gregorian calendar for official purposes since its formation, most festivals, religious dates and cultural events are determined by the Ashuran Calendar.

Music

Liberto-Ancapistanian classical music takes a distinct form to that which exists in other nations, and is closer in development to the country's folk music than other classical traditions, most notably incorporating singing and spoken poetry to a far greater extent than most classical traditions. Most classical Basaqese composers, including Idris Elahi, Rouya Shero and Ada Sabir were attached to the households of urban Santian-speaking nobility, and often incorporated the Santian language. Santia itself, which maintains a similar but distinct musical tradition, was home to more famous, household-independent composers who often grew to significant wealth in the 18th and 19th centuries, including Michele Fanzago and Nicola Capro.

Liberto-Ancapistanian popular music in post-unification years draws significantly on the musical traditions of other industrialised countries, and includes a wide variety of movements. Internationally, the most famous Liberto-Ancapistanian musical movements are forms of indie rock and contemporary folk music.

Art and Architecture

Liberto-Ancapistanian painting largely involves landscapes and wall art, and forms a long tradition dating back to at least the 200s CE. Pottery and weaving form a crucial component of traditional art, with the pottery of the Tabariere Peninsula region being famous across Evrosia for its complex patterned design. Basaqastanian and Santian art strongly influence each other, and incorporate styles from across the southern Evorisa region. The late 18th century is popularly regarded as the 'golden age of Santian art', and saw extensive wall painting across many cities in Santian cities, as well as widespread developments in music and painting. Contemporary Liberto-Ancapistanian art reflects a tradition of these currents, and continues to largely emphasise landscape or abstract painting.

The architecture of Liberto-Ancapistan includes a variety of traditions. Most traditions, including vernacular architecture in Alta Santia and much of Basaqastan, include significant use of stone and bricks, though in parts of the Cemsor Delta and Nizmstan more prominently feature wooden buildings. Many traditions emphasise height, with towers being particularly commonplace in large cities, most famously the Great Iregirs - lone-standing towers build from the 12th century in Basaqastanian cities, topped by bonfires for use in Bowist religious ritual. Modern Liberto-Ancapistanian architecture once strongly incorporated art deco, art nouveau, brutalism and other foreign styles, but since the beginning of the 21st century has moved towards a revival of traditional architectural features.

Literature and Media

Literature in Liberto-Ancapistan has a long history, most notably in the form of poetry. Poetry was primarily oral for much of Basaqastanian and Santian history, being transmitted between individuals by word of mouth, but became more common in written form following the development of Bowism in the 6th century. This was, in part, an attempt to pass down the religious teachings of the Fifth Saint of Bowism, the oral poetry of whom was written and compiled after his death into the first great work of Liberto-Ancapistanian literature, the Isahd. Most famous works of literature until the 17th century consisted of written adaptions of existing oral poems and stories, including southern Basaqastan's Cirokaniye and Upper Santia's Magario Romances.

Movements away from poetry and towards prose literature first began under the Santian Empire in the 17th century, but accelerated after the collapse of the Empire and especially industrialisation in the 1890s. Political writings by figures including Qasim Kaivan, Sayab Etyio and Fiorenza Mazzeo were a common subject of discussion throughout the 19th century and were often adapted in poetic forms for consumption by the illiterate. Modern Liberto-Ancapistan maintains a strong tradition of novel writing and community-owned libraries, often maintained in conjunction with Bowist temples. Internationally famous modern writers include Casimir Bergen, who's fame helped him to enter politics and become Chancellor in 2020.

Around 88% of Liberto-Ancapistanian households own operating televisions, and a variety of free-to-view and paid channels exist. Television broadcasting in the country dates back to the economic boom of the 1960s, during which the government of Alexandre Delon set up Ancapistan Public Broadcasting (APB) to provide education and entertainment to citizens. This remained the only television broadcasting enterprise until the early 1980s, when APB was privatised and television opened up to other companies, only being renationalised in 2020; today, it is entirely government-funded. Radio is far older in the country, and was the first form of media to spread culture across the political boundaries of early 20th century Basaqastan. The largest radio network, organised on a national and provincial level, is operated by APB. Liberto-Ancapistan also has a large newspaper industry, with province-level newspapers being especially common. This has seen change in recent years due to the increasing digitisation of news media, with the expansion of the formerly Rand-owned Compacipo Times and amalgamation of several large regional newspapers into the Basaqastan Register.

Libero-Ancapistanian cinema dates back to Santian propaganda films produced during the 1930s and 1940s, with the industry spreading to Basaqastan during the Great Santian War. Most Liberto-Ancapistanian cinema runs on a relatively low budget, and is broadly produced by the same entities as television, including APB. However, there are some exceptions, and multi-company collaborations including the 2018 adventure film Cirokaniye have seen success abroad.

Cuisine

The staple crops of Liberto-Ancapistan have historically varied between rice in southern Basaqastan, and elsewhere during wetter climate periods, and wheat in northern Basaqastan and Upper Santia. Meat, fruit and herbs are all prominent across dishes, with the former largely consisting of lamb and beef. Specific dishes vary by region, and often certain ingredients are highly region-associated - for example, milk and cheese are common in the inland provinces of Basaqastan Hundir and Rojava-Navenda, while fish is a popular ingredient in Upper Santia. Stews, kebabs and soup are the most common staples across regions, with the former and latter being incorporated into a popular national street food, the Haratnan - consisting of stew or soup being eaten while inside a hollow chunk of bread. Traditionally, both Basaqastan and Santia follow a two-meal structure, with a midday meal consumed at noon and an evening meal between 8PM and 10PM, however in recent decades a third morning meal has become more common.

Both tea and coffee are consumed in Liberto-Ancapistan, with the former grown across the country and especially common in Alta Santia Province. Desserts are typically sweet and commonly include unprepared fruits. Liberto-Ancapistan lacks a popular drinking culture as seen in many other nations, but rosé wine has traditionally been grown around the Nizmstan and is now a prestigious variety worldwide. Domestically, it is acceptable to consume the drink specifically on ceremonial occasions, including weddings and the Ashuran New Year.

Sports

Football is the most popular sport in Liberto-Ancapistan, with the average attendance of top-flight National League games being as high as 38,000. The National League is widely regarded as a key part of Liberto-Ancapistanian popular culture, and in recent years has been dominated by four teams; Bakur City, Devisgund F.C., Etarif United and Marsal City. Ancapistan Public Broadcasting has an exclusive right to domestic National League broadcasting, meaning that all games are broadcast free of charge. The second-highest league is the Federal League.

Also common in Liberto-Ancapistan is sport duelling, a traditional gun-duelling sport relatively unique to the country and drawn from the practice of gun-duelling as a legal means to settle disputes (something still legal today, but subject to a variety of restrictive conditions). The sport involves two duellists attempting to fire at each other using single-shot duelling pistols at a set distance, with the speed at which duellists can aim being the main factor of success in the sport. During duels, non-lethal wax bullets are used and protective equipment used. Duelling champions, as selected at the Annual Duelling Championship (which determines contests using a set of three duels under different rules), often become celebrities.

Other popular sports in Liberto-Ancapistan include tennis, swimming, non-duel shooting sports, and more recently Formula Conch motorsport. Liberto-Ancapistanian driver Darius Ariosto won the final grand prix in the 2024 Formula Conch season, launching him to national acclaim and popularity despite finishing 8th overall.