Choe Sŭng-min's cult of personality: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| (2 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

During his time as Chairman of the [[Supreme Council of Menghe|Supreme Council]], '''[[Choe Sŭng-min]]''' | During his time as Chairman of the [[Supreme Council of Menghe|Supreme Council]], '''[[Choe Sŭng-min]]''' built up a powerful '''{{wp|cult of personality}}''' as part of his turn toward [[Nationalism in Menghe|nationalist ideology]]. This cult originated in 1988 soon after his rise to power, but reached its dizzying peak during the 1990s and early 2000s after he consolidated his power and removed his main rivals from office. Since then, state authorities have toned down the intensity of the Choe Sŭng-min personality cult, but Choe's name and image remain a pervasive part of Menghean propaganda and public life, with a resurgence in popularity following [[Death and state funeral of Choe Sŭng-min|his death in 2021]]. | ||

At least in central state propaganda use, Choe Sŭng-min's personality cult | At least in central state propaganda use, Choe Sŭng-min's personality cult did not assign him {{wp|Apotheosis|divine status}} or magical powers, and Choe himself spoke out against any excessive praise. Instead, it focused on his attributes as a leader, emphasizing his heroism in the [[Decembrist Revolution]] and assigning him sole credit for Menghe's [[Economic reform in Menghe|economic reform]] and [[Menghean economic miracle|economic miracle]]. | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

| Line 7: | Line 7: | ||

Choe's cult of personality steadily grew in intensity during the late 1980s and early 1990s, part of an effort to propel and legitimate his consolidation of political power. After he became General-Secretary of the [[Menghean Socialist Party]] in 1993, the full force of the Party propaganda apparatus united behind the new supreme leader. At the same time, the country's opening to international trade and the formation of small private enterprises generated a surge in economic growth, for which Choe took most of the credit. | Choe's cult of personality steadily grew in intensity during the late 1980s and early 1990s, part of an effort to propel and legitimate his consolidation of political power. After he became General-Secretary of the [[Menghean Socialist Party]] in 1993, the full force of the Party propaganda apparatus united behind the new supreme leader. At the same time, the country's opening to international trade and the formation of small private enterprises generated a surge in economic growth, for which Choe took most of the credit. | ||

The Choe Sŭng-min personality cult softened somewhat in the early 2000s. This change was triggered in part by the [[1999 Menghean financial crisis]], the [[Chimgu nuclear accident]], and, somewhat later, the Menghean military's poor performance in the [[Ummayan Civil War]]. Though Choe Sŭng-min was not directly responsible for any of these crises, he was in power when they took place, and some critics allege that a pervasive pattern of top-down political interference and constant professed obedience contributed to poor management lower down the political chain of command. A rumored [[Chimgu_nuclear_accident#Political_consequences|secret meeting on 30 April 2003]] saw Choe agree to share more power with his subordinates, and after that date, state propaganda moderated their praise of Choe somewhat. | |||

==Image and portrayal== | ==Image and portrayal== | ||

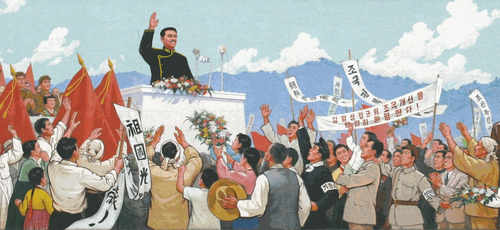

Propaganda depictions of Choe Sŭng-min often | [[Image:Choe_Propaganda_Poster_2022-02-04.png|500px|thumb|right|"Marshal Choe Sŭng-min Greets the People at Anchŏn," a propaganda painting made in 1995.]] | ||

Propaganda depictions of Choe Sŭng-min often emphasizes his visionary leadership ability, referring to him as a "guiding star" who laid out the path to national restoration. He is often shown staring off into the distance, envisioning a better future, as the rest of the country stands ready to follow him. This imagery, visual or verbal, often draws on themes of the {{wp|Confucianism#Relationships|father-son relationship}} in {{wp|Confucianism|Yuhak philosophy}}, though overt references to Choe Sŭng-min as "father" (''Ŏbŏji'') are officially discouraged. | |||

Another theme in Choe's cult of personality is connections with the past. In some images, he is juxtaposed with past Menghean emperors, including Yi Taejo and [[Kim Myŏng-hwan]]. Also noteworthy here is | Another theme in Choe's cult of personality is connections with the past. In some images, he is juxtaposed with past Menghean emperors, including Yi Taejo and [[Kim Myŏng-hwan]]. Also noteworthy here is his choice of the [[Donggwangsan]] Palace as the meeting place of the Supreme Council and his official residence; though less famous than the Vermillion Palace in Junggyŏng, it housed the Emperors of the late-19th-century Sinyi dynasty, as well as the leadership of the [[Greater Menghean Empire]]. These allusions aim to legitimize Choe's absolute rule by drawing up examples of absolute rule in the past. | ||

Menghe's [[Menghean economic miracle|economic miracle]] gave the Chairman further grounds on which to justify his rule. News and propaganda stressed that the country's rapid economic growth was a direct result of Choe's reforms and guidance, while pinning failures like the [[1999 Menghean financial crisis]] on subordinates who had deviated from Choe's example. Most scholars agree that the dramatic increase in average standards of living between 1987 and the present played the most dramatic role in generating genuine support for Choe Sŭng-min, especially among members of the rising middle class. | Menghe's [[Menghean economic miracle|economic miracle]] gave the Chairman further grounds on which to justify his rule. News and propaganda stressed that the country's rapid economic growth was a direct result of Choe's reforms and guidance, while pinning failures like the [[1999 Menghean financial crisis]] on subordinates who had deviated from Choe's example. Most scholars agree that the dramatic increase in average standards of living between 1987 and the present played the most dramatic role in generating genuine support for Choe Sŭng-min, especially among members of the rising middle class. | ||

| Line 17: | Line 20: | ||

In spite of the wide range of honors showered upon him, Choe Sŭng-min is also portrayed as humble and self-effacing. This was especially true during the [[Disciplined Society Campaign]], which was intended to crack down on the rise in crime, corruption, and lax morals that followed Menghe's meteoric economic growth. In addition to sleeping in the cold north wing of the Donggwangsan Palace and relying on Menghean-made cars and aircraft when traveling, Choe abstained from alcohol and ceased holding formal banquets, as part of an effort to display his status as a model citizen. | In spite of the wide range of honors showered upon him, Choe Sŭng-min is also portrayed as humble and self-effacing. This was especially true during the [[Disciplined Society Campaign]], which was intended to crack down on the rise in crime, corruption, and lax morals that followed Menghe's meteoric economic growth. In addition to sleeping in the cold north wing of the Donggwangsan Palace and relying on Menghean-made cars and aircraft when traveling, Choe abstained from alcohol and ceased holding formal banquets, as part of an effort to display his status as a model citizen. | ||

As part of this self-effacing image, Choe | As part of this self-effacing image, Choe ordered state cultural, news, and propaganda agencies to avoid any excessively flattering rhetoric, especially claims which border on the divine. There is apparently more than mere show to this order, as Choe's cult of personality distinctly omits any supernatural or magical elements, such as thanking the Chairman for a period of good weather preceding a harvest. Especially after the mid-2000s, state propaganda agencies have refrained from making any dramatically exaggerated claims about Choe, on the basis that these could erode any popular belief in more truthful statements. The trend toward more modest praise continues up to the present, though as a whole Choe Sŭng-min still commanded perhaps the strongest active personality cult in [[Septentrion]] at the time of his death. | ||

==Statues and portraits== | ==Statues and portraits== | ||

| Line 44: | Line 47: | ||

As in visual propaganda, Choe Sŭng-min features prominently in official Menghean songs and plays. At least half a dozen major songs have been written in his name, and dozens more directly or indirectly reference his name and accomplishments. A common theme in these songs is eternal and absolute loyalty, often coupled with the image of Choe Sŭng-min leading the nation down a path - a reference to the [[Choe_Sŭng-min_Thought#The_Path_of_National_Reconstruction|Path of National Reconstruction]], the decades-long project to restore Menghe to its rightful position of greatness. | As in visual propaganda, Choe Sŭng-min features prominently in official Menghean songs and plays. At least half a dozen major songs have been written in his name, and dozens more directly or indirectly reference his name and accomplishments. A common theme in these songs is eternal and absolute loyalty, often coupled with the image of Choe Sŭng-min leading the nation down a path - a reference to the [[Choe_Sŭng-min_Thought#The_Path_of_National_Reconstruction|Path of National Reconstruction]], the decades-long project to restore Menghe to its rightful position of greatness. | ||

During the 1990s, Choe Sŭng-min expressed a particular affinity for one such song, ''Following the Leader and the Party for Tens of Millions of Miles.'' It regularly played at official events and ceremonies, to the point that it became something of an unofficial second anthem for Menghe. In 1997 the [[National Assembly (Menghe)|National Assembly]] | During the 1990s, Choe Sŭng-min expressed a particular affinity for one such song, ''Following the Leader and the Party for Tens of Millions of Miles.'' It regularly played at official events and ceremonies, to the point that it became something of an unofficial second anthem for Menghe. In 1997 the [[National Assembly (Menghe)|National Assembly]] floated a bill to adopt the song as Menghe's new national anthem, but Choe himself ultimately pushed to table the motion, reluctant to reject the time-honored [[Let Morning Shine on These Mountains and Rivers]]. | ||

Choe Sŭng-min has also been featured in films, plays, and special television segments documenting his accomplishments. In some of the shorter segments, he has even appeared personally in place of an actor. | Choe Sŭng-min has also been featured in films, plays, and special television segments documenting his accomplishments. In some of the shorter segments, he has even appeared personally in place of an actor. | ||

| Line 54: | Line 57: | ||

==Titles and terms of address== | ==Titles and terms of address== | ||

In diplomatic address, conversation, and written exchange, Choe Sŭng-min's name | In diplomatic address, conversation, and written exchange, Choe Sŭng-min's name was followed by the Menghean honorific suffix {{wp|Korean_honorifics#Less_common_forms_of_address|Gakha}}, roughly equivalent to "His Excellency" or "His Highness." Similarly, his titles are almost always given the suffix "{{wp|Korean_honorifics#-nim|-nim}}" (e.g., ''Janggunnim'' for "General," ''Suryŏngnim'' for "Leader"). Though his most powerful political post was [[Chairman of the Supreme Council of Menghe]], he was more often addressed by his military titles, especially as ''Wŏnsunim'' or "Marshal," at the height of his power. | ||

Choe and the Party | Choe and the Party opposed the use of "Emperor" or "Imperial" to refer to Choe Sŭng-min, as this would contradict Menghe's anti-imperialist rhetoric. Nevertheless, Choe is occasionally honored as ''Sŏndae Hwangje'' (Modern Emperor) or ''Daeje'' (Great Leader) in non-state media. Low-ranking officials are not required to {{wp|kowtow}} in his presence, as they were under [[Kim Myŏng-hwan]], but they are expected to stand at attention when greeted. | ||

In songs and propaganda posters, Choe is often addressed as "Comrade" (''Choe Sŭng-min Dongji''), though this practice has grown less common in recent years. In most circumstances it would | In songs and propaganda posters, Choe is often addressed as "Comrade" (''Choe Sŭng-min Dongji''), though this practice has grown less common in recent years. In most circumstances it would have been considered improper for another person to directly address Choe as "comrade." | ||

==Choe Sŭng-min's reaction to his cult of personality== | ==Choe Sŭng-min's reaction to his cult of personality== | ||

| Line 70: | Line 73: | ||

* [[Choe Sŭng-min Thought]] | * [[Choe Sŭng-min Thought]] | ||

* [[Collected Quotations from Choe Sŭng-min]] | * [[Collected Quotations from Choe Sŭng-min]] | ||

* [[ | * [[Death and state funeral of Choe Sŭng-min]] | ||

[[Category:Menghe]] | [[Category:Menghe]] | ||

Latest revision as of 17:11, 3 September 2022

During his time as Chairman of the Supreme Council, Choe Sŭng-min built up a powerful cult of personality as part of his turn toward nationalist ideology. This cult originated in 1988 soon after his rise to power, but reached its dizzying peak during the 1990s and early 2000s after he consolidated his power and removed his main rivals from office. Since then, state authorities have toned down the intensity of the Choe Sŭng-min personality cult, but Choe's name and image remain a pervasive part of Menghean propaganda and public life, with a resurgence in popularity following his death in 2021.

At least in central state propaganda use, Choe Sŭng-min's personality cult did not assign him divine status or magical powers, and Choe himself spoke out against any excessive praise. Instead, it focused on his attributes as a leader, emphasizing his heroism in the Decembrist Revolution and assigning him sole credit for Menghe's economic reform and economic miracle.

History

When he led his troops into People's Square on December 21st, 1987, Choe Sŭng-min was virtually unknown to the vast bulk of the Menghean population. As he maneuvered to eliminate his rivals in the Interim Council for National Restoration, he quickly moved to address this weakness with a sustained propaganda campaign carried out through state agencies re-staffed by his close allies in the military. Footage of his speeches from People's Square was broadcast around the country, and state news networks credited him with the idea for decollectivizing Menghe's agricultural sector and organizing famine relief. As a result, while Choe remained something of a first among equals in the Supreme Council of the newly formed Socialist Republic of Menghe, most of the population recognized him as the highest authority in the country.

Choe's cult of personality steadily grew in intensity during the late 1980s and early 1990s, part of an effort to propel and legitimate his consolidation of political power. After he became General-Secretary of the Menghean Socialist Party in 1993, the full force of the Party propaganda apparatus united behind the new supreme leader. At the same time, the country's opening to international trade and the formation of small private enterprises generated a surge in economic growth, for which Choe took most of the credit.

The Choe Sŭng-min personality cult softened somewhat in the early 2000s. This change was triggered in part by the 1999 Menghean financial crisis, the Chimgu nuclear accident, and, somewhat later, the Menghean military's poor performance in the Ummayan Civil War. Though Choe Sŭng-min was not directly responsible for any of these crises, he was in power when they took place, and some critics allege that a pervasive pattern of top-down political interference and constant professed obedience contributed to poor management lower down the political chain of command. A rumored secret meeting on 30 April 2003 saw Choe agree to share more power with his subordinates, and after that date, state propaganda moderated their praise of Choe somewhat.

Image and portrayal

Propaganda depictions of Choe Sŭng-min often emphasizes his visionary leadership ability, referring to him as a "guiding star" who laid out the path to national restoration. He is often shown staring off into the distance, envisioning a better future, as the rest of the country stands ready to follow him. This imagery, visual or verbal, often draws on themes of the father-son relationship in Yuhak philosophy, though overt references to Choe Sŭng-min as "father" (Ŏbŏji) are officially discouraged.

Another theme in Choe's cult of personality is connections with the past. In some images, he is juxtaposed with past Menghean emperors, including Yi Taejo and Kim Myŏng-hwan. Also noteworthy here is his choice of the Donggwangsan Palace as the meeting place of the Supreme Council and his official residence; though less famous than the Vermillion Palace in Junggyŏng, it housed the Emperors of the late-19th-century Sinyi dynasty, as well as the leadership of the Greater Menghean Empire. These allusions aim to legitimize Choe's absolute rule by drawing up examples of absolute rule in the past.

Menghe's economic miracle gave the Chairman further grounds on which to justify his rule. News and propaganda stressed that the country's rapid economic growth was a direct result of Choe's reforms and guidance, while pinning failures like the 1999 Menghean financial crisis on subordinates who had deviated from Choe's example. Most scholars agree that the dramatic increase in average standards of living between 1987 and the present played the most dramatic role in generating genuine support for Choe Sŭng-min, especially among members of the rising middle class.

In spite of the wide range of honors showered upon him, Choe Sŭng-min is also portrayed as humble and self-effacing. This was especially true during the Disciplined Society Campaign, which was intended to crack down on the rise in crime, corruption, and lax morals that followed Menghe's meteoric economic growth. In addition to sleeping in the cold north wing of the Donggwangsan Palace and relying on Menghean-made cars and aircraft when traveling, Choe abstained from alcohol and ceased holding formal banquets, as part of an effort to display his status as a model citizen.

As part of this self-effacing image, Choe ordered state cultural, news, and propaganda agencies to avoid any excessively flattering rhetoric, especially claims which border on the divine. There is apparently more than mere show to this order, as Choe's cult of personality distinctly omits any supernatural or magical elements, such as thanking the Chairman for a period of good weather preceding a harvest. Especially after the mid-2000s, state propaganda agencies have refrained from making any dramatically exaggerated claims about Choe, on the basis that these could erode any popular belief in more truthful statements. The trend toward more modest praise continues up to the present, though as a whole Choe Sŭng-min still commanded perhaps the strongest active personality cult in Septentrion at the time of his death.

Statues and portraits

Choe Sŭng-min's image is an omnipresent feature of public and political life in Menghe. His statue adorns public squares and government buildings across the country; an independent estimate in 2011 determined that there were more statues of Choe Sŭng-min than any other living political leader in Septentrion, though some have questioned its methodology.

By law, all primary and secondary schools must include Choe Sŭng-min's portrait at the head of the classroom, and most Party and government buildings at the local level include a portrait somewhere on the premises. While not required, it has become fashionable for citizens to hang a portrait of the Chairman at a place of honor in their home, especially if the resident is a member of the Menghean Socialist Party. The most widely-used portrait, The General in December, is based on a photo taken on December 22nd, the day after the Decembrist Revolution.

Choe's face also appears on the front of the ₩1000 bill, with the Donggwangsan palace on the reverse. For a period after the 1997 Lèse-majesté law was passed, it was unclear whether the bills were considered "formal depictions of the Chairman's image;" a 1998 law clarified that defacement of ₩1000 bills was covered by milder laws on the destruction of currency.

In mass media

His will is the victory of the people,

Along the path which he laid out

Tens of millions advance like a storm!

Great Comrade Choe Sŭng-min,

We will follow only you!

Great Comrade Choe Sŭng-min,

Yi Gyŏng-a, Lyrics of "We know nobody but you," composed 1999

As in visual propaganda, Choe Sŭng-min features prominently in official Menghean songs and plays. At least half a dozen major songs have been written in his name, and dozens more directly or indirectly reference his name and accomplishments. A common theme in these songs is eternal and absolute loyalty, often coupled with the image of Choe Sŭng-min leading the nation down a path - a reference to the Path of National Reconstruction, the decades-long project to restore Menghe to its rightful position of greatness.

During the 1990s, Choe Sŭng-min expressed a particular affinity for one such song, Following the Leader and the Party for Tens of Millions of Miles. It regularly played at official events and ceremonies, to the point that it became something of an unofficial second anthem for Menghe. In 1997 the National Assembly floated a bill to adopt the song as Menghe's new national anthem, but Choe himself ultimately pushed to table the motion, reluctant to reject the time-honored Let Morning Shine on These Mountains and Rivers.

Choe Sŭng-min has also been featured in films, plays, and special television segments documenting his accomplishments. In some of the shorter segments, he has even appeared personally in place of an actor.

Lèse-majesté

In 1997, the National Assembly passed a law making it illegal to defame the Chairman of the Supreme Council, deliberately deface his image, or create and distribute disrespectful caricatures depicting him. The third provision effectively prohibits the use of Choe Sŭng-min in political cartoons, with the exception of favorable propaganda images approved by state censors. A supplementary clause, reportedly added at Choe Sŭng-min's request, protects general criticism of the Chairman, "as long as such criticism is productive and respectful."

Depending on the severity of the offense, the punishments can range from monetary fines to imprisonment. They are applicable to both Menghean citizens and foreign nationals, as long as the crime was committed on Menghean territory. Blanket enforcement during the late 1990s and early 2000s resulted in over a hundred cases per year, but today the law is mainly used in targeted prosecutions of high-profile dissidents.

Titles and terms of address

In diplomatic address, conversation, and written exchange, Choe Sŭng-min's name was followed by the Menghean honorific suffix Gakha, roughly equivalent to "His Excellency" or "His Highness." Similarly, his titles are almost always given the suffix "-nim" (e.g., Janggunnim for "General," Suryŏngnim for "Leader"). Though his most powerful political post was Chairman of the Supreme Council of Menghe, he was more often addressed by his military titles, especially as Wŏnsunim or "Marshal," at the height of his power.

Choe and the Party opposed the use of "Emperor" or "Imperial" to refer to Choe Sŭng-min, as this would contradict Menghe's anti-imperialist rhetoric. Nevertheless, Choe is occasionally honored as Sŏndae Hwangje (Modern Emperor) or Daeje (Great Leader) in non-state media. Low-ranking officials are not required to kowtow in his presence, as they were under Kim Myŏng-hwan, but they are expected to stand at attention when greeted.

In songs and propaganda posters, Choe is often addressed as "Comrade" (Choe Sŭng-min Dongji), though this practice has grown less common in recent years. In most circumstances it would have been considered improper for another person to directly address Choe as "comrade."

Choe Sŭng-min's reaction to his cult of personality

In the early 2000s, Choe began taking steps to rein in his now-rampant cult of personality. At the Fourth Party Conference in 2003, he delivered a speech on the dangers of excessive devotion, criticizing his most ardent supporters as "intoxicated with praise" and calling for a more moderate tone. These calls went mostly unanswered until 2005, when the Menghean Armed Forces' poor performance in the Ummayan Civil War compelled military officials to implement drastic reforms. Seizing on this opportunity, Choe stressed the importance of pragmatism and "honest criticism," blaming the military's poor performance on its inflated confidence in its ability. By implication, he also encouraged honest criticism of his own actions, giving favorable accounts of top officials who had provided valuable advice or shifted his perspective on policy.

This connection was made explicit at the Fifth Party Conference in 2007, where Choe fiercely attacked a prefecture head in Gangwŏn Province who had lagged behind in economic restructuring but spent state development funds on a monument to Choe at a site where he had worked as a revolutionary aide-de-camp. From that point onward, Choe Sŭng-min's cult of personality has steadily grown more moderate, though it shows no signs of disappearing.

Foreign scholars, however, have noted that apparent efforts to rein in Choe's personality cult only amounted to a change in its form. The Chairman's renunciation of excessive praise was carefully structured to build on his existing image as a humble and selfless model citizen, and his praise of pragmatism was itself firmly grounded in Choe Sŭng-min Thought. Even "honest criticism," many note, does not extend to criticism of the fundamental aims of state policy, only to efforts to fine-tune its implementation, a project which reinforces state authority rather than challenging it.