Menghean Won

| 대멩 인민폐 Dae Meng Inminpye | |

|---|---|

Won Banknotes currently in circulation | |

| ISO 4217 | |

| Unit | |

| Plural | The language(s) of this currency do(es) not have a morphological plural distinction. |

| Symbol | ₩ |

| Nickname | Wŏn (圓/원) |

| Denominations | |

| Subunit | |

| 1⁄100 | Jŏn (錢/전) (discontinued) |

| Banknotes | |

| Freq. used | 50, 100, 500, 1000, 5000 Wŏn |

| Coins | |

| Freq. used | 1, 5, 10 Wŏn |

| Rarely used | 10, 50 Jŏn |

| Demographics | |

| Official user(s) | |

| Unofficial user(s) | Republic of Innominada |

| Issuance | |

| Central bank | Menghean Central Bank |

| Website | english.nationalbank.mh |

| Valuation | |

| Inflation | 2.92% (2016) |

| Method | CPI |

The Menghean Inminpye (Gomun: 大孟人民幣, Sinmun: 대멩 인민폐, pr. Dae Meng Inminpye, lit. "Menghean People’s Currency"; sign ₩; ISO 4217: MIP) is the official currency of the Socialist Republic of Menghe. Its main unit is the Wŏn (圓/원, abbr. ₩), which is further divided into one hundred Jŏn. It was introduced in February 1989 as a replacement for the DPRM’s Inminpye, which had experienced high rates of inflation in the 1980s and the immediate post-revolution period. Colloquially, especially internationally, Menghean Won (officially Romanized with accent as Wŏn) may be used to refer to the currency as a whole, a practice which became more common after the Jŏn coins were withdrawn from circulation. The Dae Meng Inminpye is issued by the Menghean Central Bank (대멩사회주의궁화국 중앙은행, Daemeng Sahoejuŭi Gonghwaguk Jungang Ŭnhaeng) , and printed and minted at the National Mint in Donggyŏng.

Etymology

Since the late 19th century (see below) Menghean currency has been known as Wŏn, often Romanized as "Won" under the old Heikkinen-Järvinen transliteration system. This comes from the traditional Gomun character 圓, or "round," which refers to the circular shape of the coin. Won was the official name of the currency under the State of Sinyi, the Federative Republic of Menghe, the Greater Menghean Empire, and the Republic of Menghe.

Use of the term Inminpye, and the ISO 4217 abbreviation IMP, was made official in 1965 and printed on all coins and paper notes, but Won remained widespread in both international and colloquial settings (as it does today). Following the revaluation of the IMP in 1989, it became known as the Dae Meng Inminpye, or "Menghean People’s Currency." The government officially recognizes the abbreviations IMP and MIP; the latter is more common, and is used in the Won's ISO 4217 currency code. Technically, Wŏn only refers only to the higher unit of currency as opposed to the Jŏn, not the currency itself – as with pound and sterling. Yet internationally and domestically, it is often known as the Wŏn, a practice which became even more common after the 10 and 50-Jŏn coins were withdrawn from service. Today, Inminpye remains the official name of the currency but it is mostly reserved for formal or bureaucratic contexts.

History

Many ancient tombs in the upper Ryongtan valley, some dating to the 9th century BCE, contain copper coins in the shape of spades or knives. These are believed to be among the first metal coins used in Septentrion. During the early Yang Period (c. 300 BCE), Imperial mints began to issue copper coins in the form of a circle with a square hole at the center, which allowed them to be easily stacked in a column or tied together on a string. Emperor Sŏngmyŏng (reigned 221-257 BCE) abolished all other forms of currency during his rule, though regional currencies would resurface during the Second Warring States Period (278-715 CE).

The treasury of the Sunghwa dynasty standardized the Imperial currency again in 945 CE. In 1190 it attempted to replace this with printed paper money, the world’s first fiat currency. Excessive printing to finance infrastructure projects, combined with pervasive counterfeiting by local officials, resulted in high rates of inflation, and Emperor Taejong of the Ŭi Dynasty implemented a new standardized coin system based on a fixed ratio of gold and silver. The Myŏn Dynasty also used silver-backed currency, but colonial mining and trade upset the gold-to-silver ratio in local trade, requiring a series of devaluations that upset the domestic market.

The State of Sinyi, which broke away from the Myŏn Dynasty in 1847, issued a new currency known as the Wŏn in 1853. This was the first Menghean currency to bear the Wŏn name. Modeled after modern Western currencies, it combined coins minted in copper with paper money for higher values, and was backed by the gold standard. The State of Namyang also experimented with printed money on the silver standard, but it remained plagued by revaluations and inflation, and the new currency system used after Menghe’s reunification was based on the Sinŭi Wŏn. This Won remained in use through 1944, and in 1938 it was joined by the South Sea International Won (남해 국제적인 원, pr. Namhae Gukjejŏgin Wŏn), intended to serve the common market of the Greater Southern Sea Co-Prosperity Sphere. The Won suffered heavy inflation in the 1940s as the government began a campaign of excessive printing to finance the Pan-Septentrion War, and again in the famine period of the late 1940s, leading to a revaluation in 1949 that formed the Republic of Menghe Won.

After coming to power in 1964, the Menghean People's Communist Party replaced this with a new legal tender, known as the Inminpye or people’s currency. It forbade the use of "Won" in state papers, though this law was seldom enforced in everyday life. A pure fiat currency, the Inminpye also suffered inflation in later years, especially during the famine and budget shortfall period of the early to middle 1980s.

The Menghean government worked to slow inflation after coming to power in December 1987, and while it succeeded in driving down inflation below a 5% annual level, the black market exchange rate hovered around 100,000 Won to one Septentrion International Dollar. To ease the cumbersome value, which required people to carry around stacks of 1,000-IMB notes, the regime carried out a redenomination of the currency in February 1989. The new notes and coins, labeled as Dae Meng Inminpye, were exchanged for old Inminpye at a rate of 1 to 10,000, and the official international exchange rate was revised to to 12 MIP per 1 SID. The new bills resembled those used today, marked in Wŏn and Jŏn rather than IMB and Pun (分/푼), though the bill design was revised in subsequent years to slightly modify the cover and rear designs and implement new security features.

Value

Current (2017) nominal international exchange rates hover around 22.4 Menghean Wŏn to one Septentrion International Dollar. The international value of the Wŏn is informally pegged to a basket of other currencies, a move intended to protect against sudden swings due to speculation on the international stock market. This also gives the Menghean Central Bank considerable leeway to influence the MIP’s value. From the 1990s onward, it steadily depreciated the MIP on international markets, a move intended to make Menghean exports and manufactured goods appear cheaper in international trade.

Estimates adjusted for purchasing power parity bring the value of the MIP closer to 12.3 Wŏn per SID, again using 2016 data. This rate, however, obscures further differences between actual prices. During the 1990s, when international exchange was still tightly controlled, the Menghean government subsidized certain staple goods such as rice and bread, while also imposing high sales taxes on “luxury goods” such as cellphones and automobiles. The notorious “luxury tax” was often applied more frequently to foreign imports, leading some international corporations to accuse the Menghean government of using it as a non-tariff barrier. For its part, the Menghean government maintained (and still maintains) that the higher quality and potential status value of foreign imports makes them more likely to qualify as consumer luxuries.

During the late 1990s and early 2000s, the Menghean government gradually relaxed these price controls, as a response to stabilized agricultural production and an effort to open the country to more international trade. Yet staple crop subsidies, luxury taxes, and low monthly wages mean that basic necessities are cheaper than the international market rate in the Socialist Republic of Menghe while many higher-end consumer goods remain more expensive.

Design

Coins

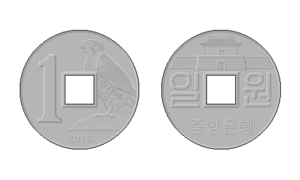

Modern Menghean coins are easily recognizable by their shape, with a square hole at the center (or a circular hole in the discontinued 10 and 50 Jŏn coins). This refers back to the traditional coins used during Menghe history, beginning in the State of Yang period, which allowed many coins to be carried on a string. The Federative Republic of Menghe eliminated the square hole when it announced its new currency design on reunification, a move intended to follow Western fashion; the center-hole layout was not revived until the revaluation of the Menghean Wŏn in 1989.

On revaluation, Menghean coins came in denominations of 10 Jŏn, 50 Jŏn, 1 Wŏn, and 5 Wŏn. The former two are coppery in color, and the latter two appear silver, though both are made of differing copper alloys (see table below). They also differed in size and thickness, with both of these increasing in line with the coin’s value. The 50 Jŏn and 5 Wŏn coins have reeding along the outer edges, while the 10 Jŏn and 1 Wŏn coins are smooth. These measures, along with the use of round holes on Jŏn coins, were intended to aid in automatic processing measures and in assessment by the visually impaired.

In 2002, to replace the ₩10 note being withdrawn from service, the National Mint introduced a ₩10 coin. Continuing the earlier trend, this is larger and heavier than its predecessors, with a square hole at the center. It is gold in color, but actually made of brass, and differs slightly in layout from the other Wŏn coins by having the number value at the top center of the obverse side.

Several years later, in 2008, the National Mint decided to withdraw the Jŏn from circulation. Inflation had further decreased its value, which was already low, and the coin cost more to manufacture than it was actually worth. Many commercial businesses had already adopted the practice of rounding after-tax prices to the nearest single Wŏn, and many vending machines no longer accepted the small coins. After 2008, this policy is official at all registered businesses, which are also forbidden from issuing Jŏn as change. As late as 2014, small merchants in rural areas still sometimes traded in Jŏn, especially when peddling cheap goods or haggling over exact prices.

| Value | $ equivalent, 2016 | Material | Obverse | Reverse | Diameter |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| J10 | $0.004 | Brass: 60% copper, 40% zinc | Numeral "10" top and center; "Jŏn" below | Chrysanthemum pattern around the center hole; "Central Bank" above; year of minting below | 14 mm |

| J50 | $0.02 | Bronze: 88% copper, 12% zinc | Numeral "50" top and center; "Jŏn" below | Cherry Blossom pattern around the center hole; "Central Bank" above; year of minting below | 17.4 mm |

| ₩1 | $0.04 | Cupronickel: 75% copper, 25% nickel | Numeral "1" on left; Donghae falcon on right; year of minting below | Yŏnghwa Gate of Dongchŏn above; “One Wŏn” on either side of the hole; "Central Bank" below | 21 mm |

| ₩5 | $0.22 | Cupronickel: 75% copper, 25% nickel | Numeral "5" on left; Buksi pagoda on right; year of minting below | View of Mount Boksan above; "Five Wŏn" on either side of the hole; "Central Bank" below | 24 mm |

| ₩10 | $0.44 | Brass: 65% copper, 35% zinc | Numeral "10" above; sheaves of wheat on either side; year of minting below | Sun rays with Mengguk star at the center; "Ten Wŏn" on either side of the hole; "Central Bank" below | 26.8 mm |

Bills

When the Menghean government implemented the Dae Meng Inminpye in 1989, Wŏn bills were available in denominations of ₩10, ₩50, ₩100, and ₩500, with labor-themed designs inspired by the old IMP notes. These still survive on the 50 through 100 bills today, though with some minor modifications.

In 1994 the Menghean government issued a new ₩1000 note, equivalent to about $70 SID at the time. The obverse side features the official portrait of Choe Sŭng-min.

The National Mint also modified the ₩50 note in 1997, adding the Bureau of Industry and Trade tower to the background on the obverse side. Completed the previous year, it briefly held the world record as the tallest building in Hemithea; at 390.2 meters to the tip of the spires, it is still the tallest concrete-based building in the world, and it remains a symbol of the Menghean economic miracle. On the reverse side, the National Mint replaced the image of the Great Ryongtan Dam with a view of Mount Hwasan, complete with the ancient calligraphy 五嶽獨尊 (O’ak Dokjon, "Most Revered of the Five Summits"). It carried out a similar revision on the ₩100 note in 1999, replacing a panoramic view of the Chikai Factory Complex with the image of Sŏsŏng Castle.

In 2002 the National Mint discontinued production of the ₩10 note, citing its declining value ($0.55 SID) and the need to reduce paper waste. As a replacement, the National Mint began minting the ₩10 coin the following year. ₩10 notes issued before then were pale gold in color, and featured two farmers, male and female, on the obverse, with an agricultural landscape on the reverse side. ₩10 notes remained in circulation for some time after the decision, but have steadily been removed from circulation; many shops today do not accept them, nor do all automatic cash machines built after 2004.

Due to similar inflationary concerns, and the growth of the economy more generally, in 2008 the government issued a new ₩5000 bill. This was unique in that it featured traditional figures and landscapes from the start, a visible homage to the golden age of the Yi dynasty. The upper leadership of the New Menghean Communist Party protested the new design as overly feudalistic, arguing that the bill should feature a modern proletarian scene. Yet the current design won out in the end, apparently receiving a strong endorsement from Choe Sŭng-min. A special edition ₩5000 note, issued in 2015, commemorated Menghean victory in the Innominadan Crisis with an image of the JCh-6 main battle tank on the reverse side.

The four smaller bills were modified again in 2010, forming the most current set. Though they are aesthetically identical to their predecessors overall, they feature a number of new security features first introduced on the ₩5000 note. The full set of measures included on all new bills now includes hidden watermarks, magnetic security thread, raised intaglio printing that feels rough to the touch, color-shifting ink on bill numbers, and micro-lettering mixed in with printed patterns.

Earlier notes remain in widespread circulation, and are accepted by most establishments, but they are slowly being withdrawn to combat counterfeiting. Bills of this series are displayed in the image to the right, with further information in the table below.

| Value | $ equivalent, 2016 | Obverse | Reverse | Dimensions |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| ₩50 | $2.23 | Model Citizens in profile, with the Bureau of Industry and Trade tower in the background and the Black Plague Memorial Tower in front of it. | Famous view of Mount Taesan bearing the ancient Gomun calligraphy "Most Revered of the Five Summits" (五嶽獨尊). | 62 × 131mm |

| ₩100 | $4.46 | Industrial worker with Chollima statue and factory complex in the background. | Sŏsŏng Castle in Baeksan Province. Suksŏng star emblem inscribed inside a gear. | 65 × 136mm |

| ₩500 | $22.32 | Families with students, including a university graduate carrying the collected quotes of Choe Sŭng-min. Cityscape of Donggyŏng in the background with an atom pattern representing nuclear energy. | The Central Hall at Donggyŏng University, the first modern university in Menghe and the most prestigious in the country. Behind it are pine trees, a bamboo forest, and a plum blossom, traditional symbols of the scholar-gentry, and a flock of rising cranes, traditional symbols of aspiration to enter government office. | 71 × 149mm |

| ₩1000 | $44.64 | Official portrait of Choe Sŭng-min, taken before the Decembrist Revolution, with beam patterns radiating outward. | Central hall of the Donggwangsan Palace in Donggyŏng, which serves as the residence of the Chairman and the meeting place of the Supreme Council. | 74 × 157mm |

| ₩5000 | $223.21 | Painted portrait of Emperor Taejong, a famous historical figure who founded the Yi dynasty, promoted the Sinmun alphabet, and made Chŏndoism the state religion. | Aerial view of the Gŭmdan-e Dosi palace complex in Chunggyŏng, with a trading junk on the right edge representing the prosperity of the Late Yi period. | 77 × 176mm |

Currency Production

Within Menghe, all printing of paper money and all minting of coins is carried out through the National Mint in the capital city. The National Mint is a state-run company (국영회사 / 國營會社, pr. Gukyŏng-Hoesa), and is subordinate to the Menghean Central Bank, which has authority over currency design and the amount of money issued. Once minted or printed, new coins and bills are stored in the Central Bank’s vault in Donggyŏng and shipped to major state-run commercial banks as requested. From there, they are given to customers making cash withdrawals, or to other state companies that issue change.

In 2001, the Menghean Central Bank revised the design of the paper Wŏn, implementing new anti-fraud features and changing the obverse and reverse images. Other than these changes, they maintain the same dimensions as the 1989 bills, and which still remain in limited circulation. On special occasions, the Central Bank has also issued unique coins and bills, such as the 2012 ₩10 coin commemorating the 25th anniversary of the Decembrist Revolution or the 2015 ₩10 coin made with the steel of Innominadan tanks destroyed in the Menghean invasion. These are identical in dimension and weight to their standard counterparts, and are regularly used in everyday exchange.

In 2013, the National Assembly ordered a study of the viability of switching to polymer banknotes with additional security features and greater durability. The Central Bank even printed a number of prospective notes for testing, though it did not circulate these publicly. Testing on these notes dispelled earlier fears that polymer notes would deform or melt when exposed to tropical heat, but the Central Bank rejected the initiative in 2015, arguing that the new bills were harder to fold and count, more expensive to produce, and would require an overhaul of the country’s ATMs and other automatic cash readers.

More recently, in early 2017, the National Assembly has brought up the possibility of moving to a cashless economy in which all transactions are performed electronically. Advocates of such a transition argue that it would be more convenient for a modern society and would create new barriers to counterfeiting and moneylaundering. It would also give the central government unprecedented power to conduct surveillance of citizens’ purchasing behavior, enforce the value of the MIP, and implement negative interest rates or controlled depreciation. Currently, there are no plans to accelerate the move toward a cashless economy or discontinue the issuance of paper money and coins, in part due to institutional conservatism at the Central Bank. But the country has nevertheless seen a steady increase in the use of electronic transactions, many of which are monitored by the government.