Valeria Valente: Difference between revisions

mNo edit summary |

mNo edit summary |

||

| (One intermediate revision by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 67: | Line 67: | ||

Valeria was married and had a large family of 10 children. She was a loving and devoted mother, and was noted for insisting on a sense of efficiency and decorum at home. She constantly experimented at home with ways to improve household activities and education, in collaboration with her family. | Valeria was married and had a large family of 10 children. She was a loving and devoted mother, and was noted for insisting on a sense of efficiency and decorum at home. She constantly experimented at home with ways to improve household activities and education, in collaboration with her family. | ||

Two of her children later wrote a well-received memoir about their upbringing, | She and her husband raised her children from an early age to be organised — to put away their toys by themselves, to clean up after themselves, and take part in household chores. She also dressed them in formal clothes at home that resembled school uniforms. Acquaintances were impressed with the "wholesome" children, who were "impeccably well-dressed, well-spoken, and well-mannered", and Valeria's habit of lining up their children from oldest to youngest for a head count whenever they went out together. | ||

Two of her children later wrote a well-received memoir about their upbringing, titled ''Tali Genitori, Tali Bambini'' ("Like Parents, Like Children"), which highlighted their parents' eccentricities and unusual but successful child-rearing methods. ''[[The Etra Echo]]'' wrote in 2016 that "it is a joy to report that ''Tali Genitori, Tali Bambini'' still reads remarkably well", praising it as "a touching family portrait that also happens to be very, very funny". | |||

Valeria's pursuit of efficiency extended to her appearance: she designed an "all-purpose, all-weather" {{wpl|greatcoat}} that she wore instead of having a wardrobe. | |||

==Legacy== | ==Legacy== | ||

Latest revision as of 17:14, 19 January 2022

Valeria Valente | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 7 April 1874 Leucarum, Cacertian Empire |

| Died | 25 September 1946 (aged 72) Etra, Free Territories |

| Nationality | Cacertian (Alscia) |

| Occupation |

|

| Known for | Leading figure of Alscia's efficiency movement |

Valeria Valente (7 April 1874 – 25 September 1946) was a Gylian psychologist, engineer, and writer. She was recognised as one of Alscia's foremost efficiency experts and the leading figure of its efficiency movement. Her writings had a great impact, influencing Gylian practices and the Gylian tradition of applied science, as well as technocracy movements in Alscia, Quenmin, and elsewhere.

Early life

Valeria was born in Leucarum, Venetio on 7 April 1874. She was the oldest surviving child of nine. Her parents were of mixed German and Gylic ancestry, but had emphasised cultural assimilation when they moved to the Cacertian Empire, and thus their children grew up learning Italian as their native language.

She had a comfortable childhood in a well-to-do family. She finished her secondary education with exemplary grades in 1892, and went on to attend the National University of Cacerta, graduating in 1896. She studied English literature, philosophy, and psychology there. She then began working towards a Ph.D. in applied psychology, which she completed in 1911.

Career

Valeria settled in Alscia after the Cacerta-Xevden War. Her dissertation was published as a book, which made her a pioneer of industrial and organizational psychology.

She founded a management consulting firm, which found favour among initially wary organised labour thanks to its emphasis on reducing effort and fatigue, with recommendations that included improved lighting, longer and more frequent breaks, suggestion boxes, and free books in the workplace.

She was also a professor at the Imperial University of Garés, where she taught industrial engineering. She established a research department for time and motion studies and home economics.

While she was best known by the public for her work in industrial engineering, her contribution to the development of the modern kitchen arguably had a greater impact: she is also credited with the invention of the foot-pedal trash can, adding shelves to the inside of refrigerator doors (including the butter tray and egg keeper), and wall-light switches, all now standard.

The publication of Un progetto per vivere meglio (A Design for Better Living) in 1914 made Valeria a leading figure in Alscia's efficiency movement, somewhat to her surprise. The book was a bestseller and translated into multiple languages. It reflected the ethos of the "hurried province" in its ceaseless attempts to increase efficiency and eliminate waste, everywhere from the home to the workplace.

One of the book's famous aphorisms was "The lazy person is the most qualified to do a difficult job, because they will find an easy way to do it."

She went on to publish additional books detailing her time and motion studies and research into home economics, but these were more technically focused and thus failed to capture the public attention of Un progetto per vivere meglio, which remains her most famous book.

Public image

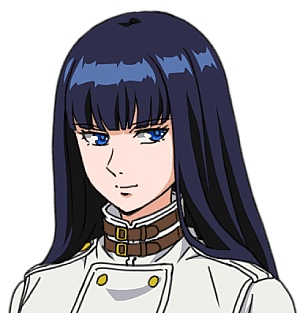

Valeria had a public reputation as a "soft-spoken fanatic", owing to her passion for efficiency and engineering knowledge. Margherita Martini described her as "strikingly beautiful", with "piercing" blue eyes and long dark hair worn in a hime cut.

While she initially had a suspicious reception in the Alscian labour movement, which was hostile to scientific management, she soon came to be respected as an ally of organised labour, due to her consistent emphasis on the importance of the "human element".

She was nicknamed "Lady Clockwork" (Donna Orologio) because her books successfully presented an appealing vision of a highly efficient society running "like clockwork", capturing the imagination of the "hurried province".

Throughout her career, Valeria remained firmly apolitical. Nevertheless, she was identified with Donatellism, and sometimes described as a "high Donatellist" because she represented the enthusiastically modernising, even proto-accelerationist elements of Donatellism. Finance minister Letizia Silvestri, a firm anti-communist, even praised Valeria for crafting a vision of utopia similar to that of Marxism, but from the angle of "engineering the misery out of capitalism".

Valeria preferred private research work over public life, but dutifully embraced her role as a leading spokesperson of the efficiency movement, and was praised for her personal charm and good humour. When PdL founder Beatrice Albini joked that people like her "will rationalise and efficientise this country to death", Valeria hung a sign on her office reading Apodotikóteta e thanatos ("Efficiency or death"), parodying the Hellene motto Eleutheria e thanatos ("Freedom or death").

She received the Order of Civic Virtue from the UOC in 1924, and was granted the title of Viscountess — her personal choice, to maintain the alliteration of her name.

Political Futurism

Valeria was strongly opposed to Political Futurism. She was utterly disgusted by the accelerationism and brutality of Political Futurism, fundamentally opposite to her humanistic vision.

She attacked the Futurist regimes of Megelan and Æþurheim in print and public speeches, and joined the Anarchofuturist Association of Alscia in solidarity with anti-Futurists.

Later life and death

Valeria remained in the Free Territories after Alscia voted to join them in 1939. Although her work was attacked by far-left radicals who associated the efficiency movement with authoritarianism and exploitation, she was defended by Alscian public figures, particularly trade unionists who highlighted her work on improving workplace conditions. She was included on the honoured citizens list.

By then in failing health, she retired from public life in 1942 and entered a nursing home. She died on 25 September 1946, aged 72. In her will, she requested that her brain be surgically removed and preserved for scientific study.

Private life

Valeria was married and had a large family of 10 children. She was a loving and devoted mother, and was noted for insisting on a sense of efficiency and decorum at home. She constantly experimented at home with ways to improve household activities and education, in collaboration with her family.

She and her husband raised her children from an early age to be organised — to put away their toys by themselves, to clean up after themselves, and take part in household chores. She also dressed them in formal clothes at home that resembled school uniforms. Acquaintances were impressed with the "wholesome" children, who were "impeccably well-dressed, well-spoken, and well-mannered", and Valeria's habit of lining up their children from oldest to youngest for a head count whenever they went out together.

Two of her children later wrote a well-received memoir about their upbringing, titled Tali Genitori, Tali Bambini ("Like Parents, Like Children"), which highlighted their parents' eccentricities and unusual but successful child-rearing methods. The Etra Echo wrote in 2016 that "it is a joy to report that Tali Genitori, Tali Bambini still reads remarkably well", praising it as "a touching family portrait that also happens to be very, very funny".

Valeria's pursuit of efficiency extended to her appearance: she designed an "all-purpose, all-weather" greatcoat that she wore instead of having a wardrobe.

Legacy

Valeria brought a major contribution to the development of Gylian engineering and industrial psychology, by applying her psychology training to time and motion studies and consistently foregrounded "the human element in scientific management". She was the first woman to teach industrial engineering in Alscia, and influenced the development of the field.

Valeria's work inspired both the Free Territories' use of applied science and Ritsuko Akagi's leadership of the Institute for the Protection of Leisure. Ritsuko sometimes wryly joked that her work consisted of "taking a copy of A Design for Better Living and scribbling bits of The Communist Manifesto on the page."

Valeria's association with the efficiency movement damaged her reputation for several decades, as her work was associated with the worst excesses of Political Futurism, Quenminese dictatorships, and capitalist exploitation. Her critics, while acknowledging Valeria's deeply principled humanism, attacked her attempts to "engineer the misery out of capitalism" as quixotic. Maria Antónia lamented that "there simply aren't enough safeguards in Valeria's books to prevent their misuse by the worst".

Her career was later reappraised more positively. Science fiction author Virginia Gerstenfeld described A Design for Better Living as "a very seductive vision of utopia", and nicknamed works with a similar tone "Va²ism" — a pun on Valeria's name. Virginia Inman wrote in Radix in 2014:

"Poor Valeria must've been beaten about by history about as badly as Adam Smith. When I decided to read A Design for Better Living, I expected to hate it on principle — the gall of its title! The know-it-all arrogance! The stench of myriad soulless imbeciles and their obsession with reducing human life to data points was overpowering.

Instead, I was pleasantly surprised to discover a book suffused with charm, subtle humour, and above all, a conviction that engineering must serve humanity, not the other way around. Valeria was a psychologist before she entered engineering, and that makes all the difference. She never attempted to engineer the soul, but merely took the technology available to her and thought profoundly how to use it to make life better for people.

Valeria presents her vision of a society as a miracle of engineering, a glorious and resilient clockwork in which everyone plays their part and there's enough room for error and to cope with the unexpected, so subtly that by the end, it's difficult not to be won over. Without intending to, she manages to turn Donatellism into poetry — this is the future our liberals want. She managed to do what nobody else could: make efficiency sexy."