Pohnpenesia: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

(hyuge WIP) |

||

| (75 intermediate revisions by the same user not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{Infobox country | {{Infobox country | ||

|micronation = | | micronation = <!--yes if a micronation--> | ||

|conventional_long_name = Country of Pohnpenesia | | conventional_long_name = Country of Pohnpenesia | ||

|native_name = | | native_name = {{unbulleted list |item_style=font-size:88%; | ||

| Taheá o Ponapa (Pohnpenesian) | | Taheá o Ponapa (Pohnpenesian) | ||

| Pais der Pohnpénésie ([[Hylia|Hylian]]) | |||

| Kontri o Ponapa (Ponape Creole) | | Kontri o Ponapa (Ponape Creole) | ||

| | |玭島 ([[Sukong|Sukongese]])}} | ||

|common_name = | | common_name = Pohnpenesia | ||

|status = | | status = Recognised as a country of [[Riamo]] with independence in foreign relations ''de jure''; operating as an independent state under Riamese protection ''de facto'' (since 1971). | ||

|image_flag = | | image_flag = [[File:Pohnpenesia flag.png|150px]] | ||

|alt_flag = | | alt_flag = <!--alt text for flag (text shown when pointer hovers over flag)--> | ||

|flag_border = | | flag_border = <!--set to no to disable border around the flag--> | ||

|image_flag2 = | | image_flag2 = <!--e.g. Second-flag of country.svg--> | ||

|alt_flag2 = | | alt_flag2 = <!--alt text for second flag--> | ||

|flag2_border = | | flag2_border = <!--set to no to disable border around the flag--> | ||

|image_coat = | | image_coat = [[File:Phonpenesia Emblem.png|100px]] | ||

|alt_coat = | | alt_coat = <!--alt text for coat of arms--> | ||

|symbol_type = | | symbol_type = seal | ||

|symbol_footnote = | | symbol_footnote = <!--optional reference or footnote for the symbol caption--> | ||

|national_motto = | | national_motto = Hana Lo Kai'i Loko | ||

|englishmotto = | | englishmotto = Glory is Found in Seas | ||

|national_anthem = | | national_anthem = <br> | ||

Hamoia oha ma Taheá o Ponapa<br>"Anthem of the Country of Pohnpenesia"<br /> | Hamoia oha ma Taheá o Ponapa<br>"Anthem of the Country of Pohnpenesia"<br /> | ||

|royal_anthem = | | royal_anthem = <!--in inverted commas and wikilinked if link exists--> | ||

|other_symbol_type = | | other_symbol_type = <!--Use if a further symbol exists, e.g. hymn--> | ||

|other_symbol = | | other_symbol = | ||

|image_map = | | image_map = <!--e.g. LocationCountry.svg--> | ||

|loctext = | | loctext = <!--text description of location of country--> | ||

|alt_map = | | alt_map = <!--alt text for map--> | ||

|map_caption = | | map_caption = <!--Caption to place below map--> | ||

|image_map2 = | | image_map2 = <!--Another map, if required--> | ||

|alt_map2 = | | alt_map2 = <!--alt text for second map--> | ||

|map_caption2 = | | map_caption2 = <!--Caption to place below second map--> | ||

|capital = | | capital = Harpan District <sup>a</sup> | ||

| coordinates = <!-- Coordinates for capital, using {{tl|coord}} --> | |||

|largest_city = | | largest_city = Harpan | ||

|largest_settlement_type = | | largest_settlement_type = | ||

|largest_settlement = | | largest_settlement = | ||

|official_languages = Pohnpenesian<br>Common Language<br> | | official_languages = Pohnpenesian<br>Common Language<br>Sukongese<br>[[Hylia|Hylian]]<small> de facto | ||

|national_languages = Ponape Creole | | national_languages = Ponape Creole | ||

|regional_languages = | | regional_languages = Boscetes Hylian | ||

| languages_type = Protected native languages | |||

|languages = | | languages = Korsannean<br>Yaapese | ||

|languages_sub = | | languages_sub = <!--Is this further type of language a sub-item of the previous non-sub type? ("yes" or "no")--> | ||

|languages2_type = | | languages2_type = <!--Another further type of language--> | ||

|languages2 = | | languages2 = <!--Languages of this second further type--> | ||

|languages2_sub = | | languages2_sub = <!--Is the second alternative type of languages a sub-item of the previous non-sub type? ("yes" or "no")--> | ||

|ethnic_groups = {{unbulleted list | | | ethnic_groups = {{unbulleted list |52.9% White| 23.6% Mixed|8.7% Native|7.2% Yellow|6.5% Black|1% other}} | ||

|ethnic_groups_year = 2021 | | ethnic_groups_year = 2021 | ||

|ethnic_groups_ref = | | ethnic_groups_ref = | ||

|religion = | | religion = {{ublist |item_style=white-space:nowrap; | ||

| | |54.4% [[Christianity]] | ||

| | |40% Irreligion | ||

| | |5.5% other}} | ||

| religion_year = 2021 | |||

|religion_year = 2021 | | religion_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with religion data)--> | ||

|religion_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with religion data)--> | | demonym = Pohnpenesian | ||

|demonym = | | government_type = Regional parliamentary democracy under a federal monarchial republic | ||

|government_type = | | leader_title1 = Monarch | ||

|leader_title1 = | | leader_name1 = [[Diana II]] | ||

|leader_name1 = [[Diana II]] | | leader_title2 = Keomoroulou | ||

|leader_title2 = | | leader_name2 = Kaimana Hilokiki | ||

|leader_name2 = Kaimana Hilokiki | | leader_title3 = Speaker of the Keuva | ||

|leader_title3 = Speaker of the Keuva | | leader_name3 = Jenni Moritsaiqe | ||

|leader_name3 = | | legislature = General ''Keuva'' | ||

| upper_house = <!--Name of governing body's upper house, if given (e.g. "Senate")--> | |||

|legislature = | | lower_house = <!--Name of governing body's lower house, if given (e.g. "Chamber of Deputies")--> | ||

|upper_house = | | sovereignty_type = Country of [[Riamo]] | ||

|lower_house = | | sovereignty_note = | ||

|sovereignty_type = | | established_event1 = Self-government | ||

|sovereignty_note = | | established_date1 = 19 September 1956 | ||

| established_event1 = Self-government | | established_event2 = Country status | ||

| established_date1 = 19 September 1956 | | established_date2 = 1 March 1971 | ||

| established_event2 = Country status | | established_event3 = E.C overthrows the local government | ||

| established_date2 = 1 March 1971 | | established_date3 = 9 February 1972 | ||

| established_event3 = E.C overthrows the local government | | established_event4 = Recognition of independence in foreign relations | ||

| established_date3 = 9 February | | established_date4 = 22 July 1988 | ||

| established_event4 = Recognition of independence in foreign relations | | established_event5 = '''E.C''' dissolves | ||

| established_date4 = 22 July 1988 | | established_date5 = 13 January 2015 | ||

| established_event5 = '''E.C''' dissolves | | area_rank = | ||

| established_date5 = 13 January 2015 | | area = | ||

|area_rank = | | area_km2 = 16,785.0 | ||

|area = | | area_sq_mi = <!--Area in square mi (requires area_km2)--> | ||

|area_km2 = | | area_footnote = <!--Optional footnote for area--> | ||

|area_sq_mi = | | percent_water = 0.30% | ||

|area_footnote = | | area_label = <!--Label under "Area" (default is "Total")--> | ||

|percent_water = 0.30% | | area_label2 = <!--Label below area_label (optional)--> | ||

|area_label = | | area_data2 = <!--Text after area_label2 (optional)--> | ||

|area_label2 = | | population_estimate = 5,900,000 | ||

|area_data2 = | | population_estimate_rank = | ||

|population_estimate = | | population_estimate_year = 2023 | ||

|population_estimate_rank = | | population_census = 5,770,234 | ||

|population_estimate_year = 2023 | | population_census_year = 2021 | ||

|population_census = | | population_density_km2 = 343.77 | ||

|population_census_year = 2021 | | population_density_sq_mi = | ||

|population_density_km2 = | | population_density_rank = | ||

|population_density_sq_mi = | | nummembers = <!--An alternative to population for micronation--> | ||

|population_density_rank = | | GDP_PPP = 90.29 billion <!--(Gross Domestic Product from Purchasing Power Parity)--> | ||

|nummembers = | | GDP_PPP_rank = | ||

|GDP_PPP = | | GDP_PPP_year = 2020 | ||

|GDP_PPP_rank = | | GDP_PPP_per_capita = 43,200.96 | ||

|GDP_PPP_year = 2020 | | GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = | ||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita = 43,200.96 | | GDP_nominal = 90.29 billion | ||

|GDP_PPP_per_capita_rank = | | GDP_nominal_rank = | ||

|GDP_nominal = 90.29 billion | | GDP_nominal_year = 2020 | ||

|GDP_nominal_rank = | | GDP_nominal_per_capita = 43,200.96 | ||

|GDP_nominal_year = 2020 | | GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = | ||

|GDP_nominal_per_capita = 43,200.96 | | Gini = 25.2 | ||

|GDP_nominal_per_capita_rank = | | Gini_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with Gini number)--> | ||

|Gini = | | Gini_rank = | ||

|Gini_ref = | | Gini_year = 2020 | ||

|Gini_rank = | | HDI_year = 2020 | ||

|Gini_year = 2020 | | HDI = 0.795 | ||

|HDI_year = | | HDI_change = decrease | ||

|HDI = | | HDI_rank = | ||

|HDI_change = | | HDI_ref = <!--(for any ref/s to associate with HDI number)--> | ||

|HDI_rank = | | currency = Ponape Hull | ||

|HDI_ref = | | currency_code = PH | ||

|currency = | | time_zone = UTC | ||

|currency_code = | | utc_offset = +6 | ||

|time_zone = | | time_zone_DST = DST | ||

|utc_offset = | | utc_offset_DST = +7 | ||

|time_zone_DST = | | DST_note = <!--Optional note regarding DST use--> | ||

|utc_offset_DST = | | antipodes = <!--Place/s exactly on the opposite side of the world to country/territory--> | ||

|DST_note = | | date_format = dd/mm/yyyy | ||

|antipodes = | | drives_on = left | ||

|date_format = | | cctld = .pn | ||

|drives_on = | | iso3166code = <!--Use to override default from common_name parameter above; omit using "omit".--> | ||

|cctld = | | calling_code = +450 | ||

|iso3166code = | | patron_saint = <!--Use patron_saints for multiple--> | ||

|calling_code = | | image_map3 = <!--Optional third map position, e.g. for use with reference to footnotes below it--> | ||

|patron_saint = | | alt_map3 = <!--alt text for third map position--> | ||

|image_map3 = | | footnote_a = <sup>The Harpan District is an administrative entity that is distinct from the actual city of Harpan. Governmental buildings are situated in the territory of Harpan District, not the City of Harpan.</sup> | ||

|alt_map3 = | | footnote_b = <!--For any footnote <sup>b</sup> used above--> | ||

|footnote_a = | <!--......-->| footnote_h = <!--For any footnote <sup>h</sup> used above--> | ||

|footnote_b = | | footnotes = <!--For any generic non-numbered footnotes--> | ||

<!--......--> | | common_languages = Canterian | ||

|footnote_h = | |||

|footnotes = | |||

}} | }} | ||

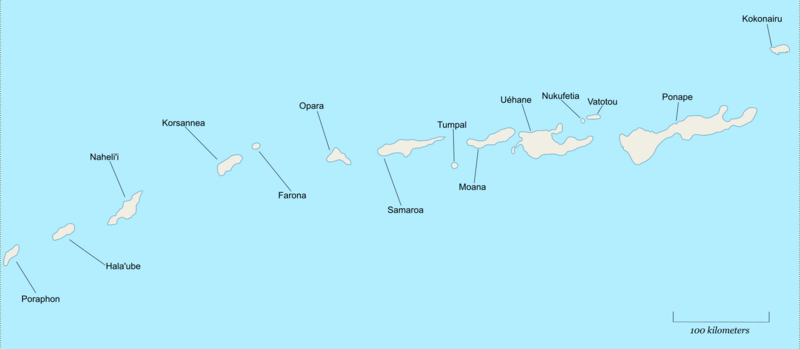

'''Pohnpenesia''', officially the '''Country of Pohnpenesia''' (Pohnpenesian: Taheá o Ponapa; Ponape Creole: Kontri o Ponapa), is an archipelago nation centered in the Kaldaz Ocean. The country occupies the Pohnpenesian | '''Pohnpenesia''', officially the '''Country of Pohnpenesia''' (Pohnpenesian: Taheá o Ponapa; Hylian: Pais der Pohnpénésie; Ponape Creole: Kontri o Ponapa; Sukongese: 玭島), is an archipelago nation centered in the Kaldaz Ocean. The country occupies the archipelago of the Pohnpenesian Island Group, made of 14 islands in various sizes. According to the National Demographic Census of 2021, over 5.77 million people inhabit the territory. The largest city and capital is Harpan, home to over 1,152,000 people, comprising around 23% of the national population. The government-owned properties and lands are mainly located in the Harpan District, which is an administrative entity separate from the city. Harpan is also the key center of transportation, culture and government activites in Pohnpenesia. | ||

Of the population, | Of the population, 52.9% identifies as White, while 23.6% identify as ethnically mixed. 8.7% identify as native Kaldaic Pohnpenesians, 7.2% identify as 'Yellow' or 'Sama', mainly Sukongese descendants, 6.5% identify as 'Black', and 1% of census takers are categorized as other. | ||

As of 1988, Pohnpenesia has been acknowledged as an autonomous legal entity, distinct from [[Riamo]]. This status empowers Pohnpenesian officials to engage in diplomatic missions and establish treaties in its own right. In the recent past, Pohnpenesia has pursued a more autonomous foreign policy, establishing direct diplomatic relationships with several countries. Nevertheless, citizens of Pohnpenesia continue to maintain Riamese nationality and certain laws that apply across the federation still apply to Pohnpenesia. | As of 1988, Pohnpenesia has been acknowledged as an autonomous legal entity, distinct from [[Riamo]]. This status empowers Pohnpenesian officials to engage in diplomatic missions and establish treaties in its own right. In the recent past, Pohnpenesia has pursued a more autonomous foreign policy, establishing direct diplomatic relationships with several countries. Nevertheless, citizens of Pohnpenesia continue to maintain Riamese nationality and certain laws that apply across the federation still apply to Pohnpenesia. | ||

Pohnpenesia has a history that dates back to 2,000 years of permanent settlement when the first settlers arrived and established the Nahakir system of governance. The Colonial Era began in the late 17th century with the arrival of Riamese colonists, who brought new technologies and crops while introducing Christianity. In the early 20th century, Pohnpenesia faced a competitive period. during the Great War when it was invaded by [[Hoterallia]]. After the war, Pohnpenesia was handed over to the Riamese Federation, gaining self-government status in the late 1950s and country status in the early 1960s, becoming a sovereign nation within the federation while still under Riamese sovereignty. The country faced economic devastation from 1988 to the dissolving in 2015, when the Equalitarian Communion overthrew the government and imposed strict policies, resulting in decades of political and economic instability. | Pohnpenesia has a history that dates back to 2,000 years of permanent settlement when the first settlers arrived and established the Nahakir system of governance. The Colonial Era began in the late 17th century with the arrival of Riamese colonists, who brought new technologies and crops while introducing Christianity. In the early 20th century, Pohnpenesia faced a competitive period. during the Great War when it was invaded by [[Hoterallia]]. After the war, Pohnpenesia was handed over to the Riamese Federation, gaining self-government status in the late 1950s and country status in the early 1960s, becoming a sovereign nation within the federation while still under Riamese sovereignty. The country faced economic devastation from 1988 to the dissolving in 2015, when the Equalitarian Communion overthrew the government and imposed strict policies, resulting in decades of political and economic instability. | ||

== Etymology == | |||

Pohnpenesia stands as an upper-middle-income economy and has a high Human Development Index (HDI). It maintains one of the lowest Gini indexes globally, measured at 25.2, and serves as a sought-after tax haven, attracting financial institutions, banks, and affluent individuals. However, despite these economic accolades, the nation grapples with enormous instability. Rampant corruption and economic insecurity plague the government, contributing to one of the highest per capita suicide rates worldwide. | |||

In July 2023, a tsunami ravaged the archipelago, unleashing one of the most severe humanitarian crises on record. During the same year, the country faced another catastrophe as it defaulted on its escalating debts, which remained unpaid for over 2 decades, leading to the declaration of bankruptcy by the national bank. The aftermath witnessed widespread power outages, a surge in violent criminal activities, and an escalation of hyperinflation, causing an economic crisis that still persists to this year. | |||

== Etymology== | |||

The word "Pohnpenesia" comes from the name of the largest island in the archipelago, Ponape. The exact origins of the name Ponape are unclear, but some scholars believe it may be derived from the word "pwun," meaning "mountain," and "pei," meaning "upon." Thus, Ponape could mean "upon the mountain." The name Pohnpenesia was likely coined by Riamese explorers during the colonial era as a way to describe the entire archipelago of islands in the region. | The word "Pohnpenesia" comes from the name of the largest island in the archipelago, Ponape. The exact origins of the name Ponape are unclear, but some scholars believe it may be derived from the word "pwun," meaning "mountain," and "pei," meaning "upon." Thus, Ponape could mean "upon the mountain." The name Pohnpenesia was likely coined by Riamese explorers during the colonial era as a way to describe the entire archipelago of islands in the region. | ||

== History == | ==History == | ||

=== Early History=== | {{under construction |placedby= |section= |nosection= |nocat= |notready= |comment=Re-writing underway |category= |altimage= }} | ||

===Early History === | |||

The earliest evidence of human habitation dates back to 3 kya, where human remains dating back to 6000 B.C were discovered. However, permanent inhabitation didn't begin until the first millenium. Being inhabited by humans since around 1 A.D, Pohnpenesia has a rich ancient history that dates back to over 2,000 years of permanent settlement. The islanders gradually developed complex systems of agriculture, fishing, and navigation, building canoes that allowed them to trade and travel across the Kaldaz and conduct trade with neighboring peoples. The Nahakir system of governance, established in 600 A.D was a decentralized system established by the peoples that divided the islands into five tribes or kingdoms, each with their own ruling clan. The clans were headed by a chief or Nahnmwarki, who was responsible for maintaining order and settling disputes within their tribe. However, the Naraha'kiki also had to work together to ensure the stability of the entire island chain, and meetings were held periodically to discuss issues affecting all tribes. The Pohnpenesians also had a system of social organization based on matrilineal descent, with inheritance passing through the mother's line. This system helped to maintain balance and prevent the concentration of power in the hands of a few individuals or families. | The earliest evidence of human habitation dates back to 3 kya, where human remains dating back to 6000 B.C were discovered. However, permanent inhabitation didn't begin until the first millenium. Being inhabited by humans since around 1 A.D, Pohnpenesia has a rich ancient history that dates back to over 2,000 years of permanent settlement. The islanders gradually developed complex systems of agriculture, fishing, and navigation, building canoes that allowed them to trade and travel across the Kaldaz and conduct trade with neighboring peoples. The Nahakir system of governance, established in 600 A.D was a decentralized system established by the peoples that divided the islands into five tribes or kingdoms, each with their own ruling clan. The clans were headed by a chief or Nahnmwarki, who was responsible for maintaining order and settling disputes within their tribe. However, the Naraha'kiki also had to work together to ensure the stability of the entire island chain, and meetings were held periodically to discuss issues affecting all tribes. The Pohnpenesians also had a system of social organization based on matrilineal descent, with inheritance passing through the mother's line. This system helped to maintain balance and prevent the concentration of power in the hands of a few individuals or families. | ||

[[File:Marshallese Rito Fans.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Pohnpenesian akaka fans]] | [[File:Marshallese Rito Fans.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Pohnpenesian akaka fans]] | ||

| Line 156: | Line 161: | ||

Art and music were also integral parts of the Pohnpenesian ancient culture. The islanders created works of art, such as intricately woven textiles (bakon), hand-carved wooden figures, and pottery. They also developed a unique musical tradition that included singing, dancing, and playing a variety of instruments, such as the bamboo flute, drums, and gongs. These artistic expressions were often tied to spiritual beliefs and practices, and they played an important role in the islanders' social and cultural life. | Art and music were also integral parts of the Pohnpenesian ancient culture. The islanders created works of art, such as intricately woven textiles (bakon), hand-carved wooden figures, and pottery. They also developed a unique musical tradition that included singing, dancing, and playing a variety of instruments, such as the bamboo flute, drums, and gongs. These artistic expressions were often tied to spiritual beliefs and practices, and they played an important role in the islanders' social and cultural life. | ||

Pohnpenesia's economy was based on agriculture, with the indigenous people cultivating yams, taro, breadfruit, coconuts, and other crops. They also engaged in fishing and hunting, using the abundant marine resources to sustain their livelihoods. Trading was also an important part of the economy, with the islanders exchanging goods with neighboring communities, including the Faio people of [[Freice]] and the | Pohnpenesia's economy was based on agriculture, with the indigenous people cultivating yams, taro, breadfruit, coconuts, and other crops. They also engaged in fishing and hunting, using the abundant marine resources to sustain their livelihoods. Trading was also an important part of the economy, with the islanders exchanging goods with neighboring communities, including the Faio people of [[Freice]], and the Pacanese of [[Pacanesia]] in the southern islands. This trade network helped the Pohnpenesians acquire goods that were not available on their islands, such as obsidian, which was used for making tools. | ||

[[File:Woman's skirt from the Marshall Islands, Honolulu Museum of Art.jpg|205px|thumb|right|Women's fabric plaiting, Museum of Archaeology (Medines)]] | [[File:Woman's skirt from the Marshall Islands, Honolulu Museum of Art.jpg|205px|thumb|right|Women's fabric plaiting, Museum of Archaeology (Medines)]] | ||

=== Kaldaic Empire | ===Kaldaic Empire=== | ||

The Pohnpenesian and Pohnpeian kingdoms and clans united in the early 13th century to form the Kaldaic Empire, which was the first centralized state in the Kaldaz Ocean. [[File:Pagaruyung palace.jpg|200px|thumb|left|16th century Layaua Palace in Naheli'i]] The Kaldaic Empire was formed through a combination of alliances, intermarriage, and conquest, and it rapidly expanded its territory to include much of the Kaldaz archipelago and parts of the neighboring Sundaic regions. The empire was ruled by an absolute monarch known as the Kaldaic Emperor, who wielded both political and religious power. The emperor was seen as a divine figure and was believed to have the power to control the weather and other natural phenomena. The Empire's wealth was bolstered by the production of highly sought-after commodities such as pearls, tortoise shells, and dried fish. | The Pohnpenesian and Pohnpeian kingdoms and clans united in the early 13th century to form the Kaldaic Empire, which was the first centralized state in the Kaldaz Ocean. [[File:Pagaruyung palace.jpg|200px|thumb|left|16th century Layaua Palace in Naheli'i]] The Kaldaic Empire was formed through a combination of alliances, intermarriage, and conquest, and it rapidly expanded its territory to include much of the Kaldaz archipelago and parts of the neighboring Sundaic regions. The empire was ruled by an absolute monarch known as the Kaldaic Emperor, who wielded both political and religious power. The emperor was seen as a divine figure and was believed to have the power to control the weather and other natural phenomena. The Empire's wealth was bolstered by the production of highly sought-after commodities such as pearls, tortoise shells, and dried fish. | ||

| Line 168: | Line 173: | ||

The Kaldaic Empire had a centralized government system with an emperor as its head. The emperor ruled over a hierarchy of officials who were responsible for governing different regions of the empire. Each island had a governor who was responsible for maintaining law and order, collecting taxes, and overseeing local affairs. The empire had a strong military force that was used to enforce the emperor's authority and maintain control over the provinces. The emperor was also responsible for appointing judges and overseeing the judicial system. The government was highly bureaucratic, with officials appointed based on merit and loyalty to the emperor. The empire had a well-organized system of record-keeping, which enabled efficient administration and communication throughout the vast empire. | The Kaldaic Empire had a centralized government system with an emperor as its head. The emperor ruled over a hierarchy of officials who were responsible for governing different regions of the empire. Each island had a governor who was responsible for maintaining law and order, collecting taxes, and overseeing local affairs. The empire had a strong military force that was used to enforce the emperor's authority and maintain control over the provinces. The emperor was also responsible for appointing judges and overseeing the judicial system. The government was highly bureaucratic, with officials appointed based on merit and loyalty to the emperor. The empire had a well-organized system of record-keeping, which enabled efficient administration and communication throughout the vast empire. | ||

==== Hylian missionaries ==== | ==== Hylian missionaries==== | ||

In the mid-17th century, a group of Christian Hylian missionaries arrived in the archipelago, marking a significant turning point in the religious and cultural landscape of the region. Driven by their faith and a desire to spread their beliefs, these missionaries set out to establish Christian communities in the archipelago. Their arrival had a profound impact on the islands of Naheli'i, Hala'ube, and Poraphon (now collectively known as the Boscetes), where they established several monasteries and built permanent settlements. | In the mid-17th century, a group of Christian Hylian missionaries arrived in the archipelago, marking a significant turning point in the religious and cultural landscape of the region. Driven by their faith and a desire to spread their beliefs, these missionaries set out to establish Christian communities in the archipelago. Their arrival had a profound impact on the islands of Naheli'i, Hala'ube, and Poraphon (now collectively known as the Boscetes), where they established several monasteries and built permanent settlements. | ||

| Line 177: | Line 182: | ||

One of the most lasting impacts of the Christian Hylian missionaries in the Boscetes was the adoption of Hylian as a Christian liturgical language. The missionaries introduced new translations of Christian texts and liturgical practices, which helped to cement the language's place in the region's religious and cultural life. | One of the most lasting impacts of the Christian Hylian missionaries in the Boscetes was the adoption of Hylian as a Christian liturgical language. The missionaries introduced new translations of Christian texts and liturgical practices, which helped to cement the language's place in the region's religious and cultural life. | ||

=== Decline and Colonial Era === | ===Decline and Colonial Era=== | ||

The Kaldaic Empire faced significant challenges in the early 18th century that contributed to its gradual decline and eventual collapse. One of the key factors was the economic decline of the empire, which was caused by several factors. The empire's economy was largely based on agriculture, fishing, and trade, but over time, these industries became less profitable due to the exhaustion of natural resources and the increasing competition from other regions. Additionally, the empire faced challenges from changing trade patterns and the arrival of new technologies, which disrupted traditional industries and markets. | The Kaldaic Empire faced significant challenges in the early 18th century that contributed to its gradual decline and eventual collapse. One of the key factors was the economic decline of the empire, which was caused by several factors. The empire's economy was largely based on agriculture, fishing, and trade, but over time, these industries became less profitable due to the exhaustion of natural resources and the increasing competition from other regions. Additionally, the empire faced challenges from changing trade patterns and the arrival of new technologies, which disrupted traditional industries and markets. | ||

| Line 195: | Line 200: | ||

The 'hele mamao' were on the top of the system, being the colonial Riamese settlers that often owned the plantations. The 'huikau' were 2nd, being the criollo bourgeoise mixed with settlers that allied with the tribes that benefited from the wars, also Hylians. They were generally prosperous and did not face much discrimination compared to the natives. On the bottom of the system were the natives and indigenous people. Despite establishing a peaceful relationship with the Riamese, the native population was often concealingly exploited financially, leading to a noticeable inequality compared with the huikau and the settlers. | The 'hele mamao' were on the top of the system, being the colonial Riamese settlers that often owned the plantations. The 'huikau' were 2nd, being the criollo bourgeoise mixed with settlers that allied with the tribes that benefited from the wars, also Hylians. They were generally prosperous and did not face much discrimination compared to the natives. On the bottom of the system were the natives and indigenous people. Despite establishing a peaceful relationship with the Riamese, the native population was often concealingly exploited financially, leading to a noticeable inequality compared with the huikau and the settlers. | ||

In 1798, the Riamese established the city of | In 1798, the Riamese established the city of Harpont, which would later become known as Harpan 2 years later, west of ancient Haraù. The city was strategically settled on the eastern coast of the island and served as a hub for trade and commerce. The Riamese were attracted to the island for its abundant natural resources, including timber, copra, and fish. They quickly established a presence on the island and began to develop infrastructure, such as docks and warehouses, to facilitate trade with the surrounding islands. | ||

[[File:Harponné.jpeg|300px|thumb|right|Gunnerton Street, Harpan circa. 1879. The oldest street in Pohnpenesia to date.]] | [[File:Harponné.jpeg|300px|thumb|right|Gunnerton Street, Harpan circa. 1879. The oldest street in Pohnpenesia to date.]] | ||

As the city of | As the city of Harpan grew, becoming the capital of the colony in 1804, it became a center of cultural exchange between the Riamese and the native Pohnpenesians. The Riamese brought with them their own traditions, including music, art, and cuisine, which were blended with the existing culture of the Pohnpenesians. The city also became home to a diverse population of immigrants from other parts of the archipelago. Despite some cultural differences and occasional conflicts, the Riamese and Pohnpenesian in the generally lived in harmony, with many forming close friendships and business partnerships. Haraù was largely separated from the urban encroachment of Harpan due to distance, and did not receive equal support, which resulted in a chunk of the population flocking to the new city for employment. | ||

[[File:HURSTHOUSE(1857) p225 AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Print of the port of | [[File:HURSTHOUSE(1857) p225 AUCKLAND, NEW ZEALAND.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Print of the port of Harpont, mid-1700s.]] | ||

In the mid-19th century, the Riamese government enacted reforms to better govern their colonial territories, including Pohnpenesia. They established a colonial administration to oversee the territory and heavily invested in infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and public buildings. They also promoted education by building new schools and encouraging enrollment for both Riamese and Pohnpenesian children, leading to significant improvements in literacy rates in Pohnpenesia. The mentality towards the natives also began to | In the mid-19th century, the Riamese government enacted reforms to better govern their colonial territories, including Pohnpenesia. They established a colonial administration to oversee the territory and heavily invested in infrastructure such as roads, bridges, and public buildings. They also promoted education by building new schools and encouraging enrollment for both Riamese and Pohnpenesian children, leading to significant improvements in literacy rates in Pohnpenesia. The negative mentality towards the natives also began to subside at this time. However, inequality still persisted. | ||

As the 19th century progressed, | As the 19th century progressed, these developments helped to modernize the country and establish a solid foundation for its future growth. | ||

Alongside these developments, Riamese Orthodoxy was introduced to Pohnpenesia by Riamese missionaries and was largely adopted by non-Boscettian natives, replacing Hylian Christianity (which had a presence in the archipelago since the 16th century). The introduction of Christianity brought about significant social and cultural changes, as the Pohnpenesians adapted to new religious beliefs and practices. Riamese Orthodoxy also played a role in the development of education and literacy, as mission schools were established to teach Christian values and provide education to the Pohnpenesia. In 1856, the Pohnpenesian Unity Church was established by local Pohnpenesia who had converted to Christianity. The church blended Christian beliefs with traditional Pohnpeneisan customs and practices, creating a unique form of Christianity that was embraced by many on the islands. The church's leaders worked to spread their faith throughout the islands, building churches and organizing missionary efforts. As a result, the sect became the most dominant in Pohnpenesia. | Alongside these developments, Riamese Orthodoxy was introduced to Pohnpenesia by Riamese missionaries and was largely adopted by non-Boscettian natives, replacing Hylian Christianity (which had a presence in the archipelago since the 16th century). The introduction of Christianity brought about significant social and cultural changes, as the Pohnpenesians adapted to new religious beliefs and practices. Riamese Orthodoxy also played a role in the development of education and literacy, as mission schools were established to teach Christian values and provide education to the Pohnpenesia. In 1856, the Pohnpenesian Unity Church was established by local Pohnpenesia who had converted to Christianity. The church blended Christian beliefs with traditional Pohnpeneisan customs and practices, creating a unique form of Christianity that was embraced by many on the islands. The church's leaders worked to spread their faith throughout the islands, building churches and organizing missionary efforts. As a result, the sect became the most dominant in Pohnpenesia. | ||

[[File:Honolulu's St. Andrew's Cathedral, from the Ewa side.jpg|200px|thumb|right|St. Deone's Cathedral in Harpan, the oldest church in Pohnpenesia built in 1859.]] | [[File:Honolulu's St. Andrew's Cathedral, from the Ewa side.jpg|200px|thumb|right|St. Deone's Cathedral in Harpan, the oldest church in Pohnpenesia built in 1859.]] | ||

=== 20th century === | ===20th century=== | ||

At the beginning of the 20th century, Pohnpenesia had made significant progress in terms of infrastructure, education, and social development. The Riamese colonial administration continued to invest in these areas, | At the beginning of the 20th century, Pohnpenesia had made significant progress in terms of infrastructure, education, and social development. The Riamese colonial administration continued to invest in these areas, building and improving transportation systems such as trains and extensive networks of ferries. However, some Pohnpenesians continued to resist colonial rule. Despite unrest, Pohnpenesia was transforming into a more stable and prosperous society, from being reliant on Riamese aid to becoming self-sufficent. During the early 20th century, the banking and financial services industry began to thrive in Pohnpenesia. One of the key factors in the success of the industry was the stability and reliability of the Pohnpeneisan government, which had maintained a stable political climate for many years, along with support from Riamo. Additionally, the archipelago's position as a major hub for trade and commerce in the Kaldaic region made it an attractive location for international banks to establish operations. The government also actively encouraged the growth of the banking industry by providing tax incentives and other benefits to companies that established themselves in Pohnpenesia. | ||

The flourishing banking and financial services industry in Pohnpenesia attracted a significant flow of expats and migrants to the country. Many foreign professionals and people from across the globe, came to Pohnpenesia seeking employment. Foreign investors also became increasingly interested in Pohnpenesia, attracted by the country's abundant natural resources and strategic location. These investors, primarily from Riamo and other developed countries, invested heavily in a range of industries, including agriculture, mining, manufacturing, and transportation. They also helped to fund large-scale infrastructure projects such as ports, airports, and major arteries. These investments brought much-needed capital and technological expertise to Pohnpenesia. | |||

Throughout the early 20th century, Pohnpenesia's tourism industry also experienced significant growth | Throughout the early 20th century, Pohnpenesia's tourism industry also experienced significant growth. The government invested in the development of tourism infrastructure, including hotels, resorts, and transportation networks. As a result, Pohnpenesia became a popular destination from across the globe. The tourism industry also provided significant economic benefits, creating jobs and generating significant revenue for the colony. | ||

[[File:Victoria beach hotel.jpg|250px|thumb|left|Pohnpenesia experienced a massive tourist boom in the early 20th century, one such relic of this era is the Victoria Beach Hotel in Pahili, constructed in 1908 and remodeled in the late 90s.]] | [[File:Victoria beach hotel.jpg|250px|thumb|left|Pohnpenesia experienced a massive tourist boom in the early 20th century, one such relic of this era is the Victoria Beach Hotel in Pahili, constructed in 1908 and remodeled in the late 90s.]] | ||

==== | ====Immigration wave ==== | ||

The massive number of migration to the archipelago resulted in rapid urbanization by 1905. In order to accommodate the new population, large-scale residential projects were built. Harpan, Nenavia and other towns ballooned in size and density as urban sprawl cleared the nature around them. This influx of migrants and expatriates began to overwhelm local infrastructure. In response, the 1908 Caterer's Act allocated over 90,500 hull to the colony for the expansion of services and public buildings. Also, the act granted citizenship by birthright to any foreign child born on Pohnpenesian soil. This provision ultimately helped subsequent waves of immigration and generational population growth to the archipelago. | |||

By 1915, Pohnpenesia's population had soared to an estimated 230,000 residents, up from just 52,000 in 1906. The number of expatriates and migrants, along with their families, not only filled existing towns and established new settlements, but began to outnumber the local population significantly. This demographic shift altered the social fabric of Pohnpenesia, leading to both 'cultural exchanges and challenges' as the newcomers integrated into the community. The majority of migrants came from Sukong, Morrawia, Kakland, Mainland Riamo, Anáhuac, and Montilla, which further facilitated cultural mixing and fundamentally altered the identity of Pohnpenesia in the decades to come. | |||

====Cursor to independence==== | |||

The | In the 1930s, the Riamese government embarked on a series of reforms and investments aimed at autonomizing Pohnpenesian society. These efforts eventually paid off, and in 1956 Pohnpenesia gained self-government status, marking a new era of political autonomy and economic growth. Under this new system, the archipelago was able to take greater control of its own affairs, charting its own course. | ||

=== | |||

Despite gaining self-government status in 1956, Pohnpenesia still faced significant challenges such as large inequality and economic instability. The newly established government struggled to address these issues and provide basic services to its citizens | Despite gaining self-government status in 1956, Pohnpenesia still faced significant challenges such as large inequality and economic instability from the war. The newly established government struggled to address these issues and provide basic services to its citizens. As a result, many Pohnpenesians began to live in poverty. The nation also saw the takeover of an infamous elite class known as the 'Vahinà'. These wealthy individuals that trace back to the Pohnpenesian elite amassed great fortunes through their control of industries such as agriculture and mining, as well as their involvement in the government. The Vahinà class became known for their extravagant lifestyles and their corrupt practices, including bribery and embezzlement of public funds. | ||

[[File:Aerial view of Waikiki, with Diamond Head in the background, circa in 1956.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Aerial view of O'hira, an important resort town on the island of Samaroa, circa. 1956. ]] | [[File:Aerial view of Waikiki, with Diamond Head in the background, circa in 1956.jpg|200px|thumb|left|Aerial view of O'hira, an important resort town on the island of Samaroa, circa. 1956. ]] | ||

Their influence on the political climate of Pohnpenesia was significant, as they held great sway over government officials and were often able to dictate policy decisions to their own benefit. This further exacerbated inequality and economic instability, as the Vahinà class monopolized resources and opportunities at the expense of the general population. | Their influence on the political climate of Pohnpenesia was significant, as they held great sway over government officials and were often able to dictate policy decisions to their own benefit. This further exacerbated inequality and economic instability, as the Vahinà class monopolized resources and opportunities at the expense of the general population. | ||

However, despite the economic instability | However, despite the economic instability that plagued Pohnpenesia in the early during this period, the finance and banking industry still managed to thrive. The industry buffed a strong foundation laid by foreign banks during the colonial mandate period, which provided the necessary infrastructure and trained personnel to support the growth of local banks. Pohnpenesian banks benefited from favorable regulations and access to capital from foreign investors, allowing them to expand and provide a range of services such as loans, mortgages, and insurance. The finance and banking industry continued to be a major contributor to the country's economy, and its success provided help for combatting the downturn of the economy. | ||

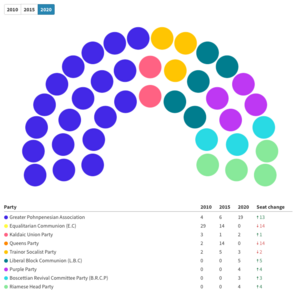

==== Country status & the rise of Equalitarianism ==== | ====Country status & the rise of Equalitarianism==== | ||

In the early 1970s, Pohnpenesia was still struggling with issues of inequality and economic instability. However, the country was making progress in establishing itself as an independent and autonomous legal entity. On March 1st of 1971, Pohnpenesia was granted full country status, recognizing its sovereignty as a distinct nation within the Riamese Federation. | In the early 1970s, Pohnpenesia was still struggling with issues of inequality and economic instability. However, the country was making progress in establishing itself as an independent and autonomous legal entity. On March 1st of 1971, Pohnpenesia was granted full country status, recognizing its sovereignty as a distinct nation within the Riamese Federation. | ||

The Equalitarian Communion, or simply the E.C., emerged as a significant political force in Pohnpenesian society in the early 1970s. The movement was founded on the principles of egalitarianism and socialism, advocating for the equal distribution of wealth and resources and the dismantling of existing power structures that perpetuated inequality. The E.C. gained momentum through grassroots organizing and social activism, drawing support from various segments of society, including workers, farmers, and marginalized groups. Their message of social justice resonated with many Pohnpenesians who had been marginalized and excluded from the benefits of the country's economic upturns throughout century. | |||

In the 1972 National Election, the E.C. rose to power in Pohnpenesia, winning a majority of seats in the national parliament. The party's leader, Tuhinga Rama, became the country's first E.C.-affiliated Prime Minister, leading a government that sought to implement radical social and economic reforms. These reforms included land and wealth redistribution, public ownership of key industries, and the establishment of social welfare programs aimed at providing basic services to all citizens. | |||

In the 1972 National Election, the E.C. rose to power in Pohnpenesia, winning a majority of seats in the national parliament. The party's leader, Tuhinga Rama, became the country's first E.C.-affiliated Prime Minister, leading a government that sought to implement radical social and economic reforms. These reforms included land and wealth redistribution, public ownership of key industries, and the establishment of social welfare programs aimed at providing basic services to all citizens. | |||

[[File:Malietoa Tanumafili II (cropped).jpg|200px|thumb|Tuhinga Rama on Election Day, circa. 1972]] | [[File:Malietoa Tanumafili II (cropped).jpg|200px|thumb|Tuhinga Rama on Election Day, circa. 1972]] | ||

The rise of the E.C. was also fueled by growing resentment towards the wealthy and powerful Vahinà class. | The rise of the E.C. was also fueled by growing resentment towards the wealthy and powerful Vahinà class. Their perceived greed and corruption ultimately led to their downfall. In 1973, a violent uprising led by the E.C. resulted in the collapse of the Vahinà's power structure, with dozens being massacred and their homes burned down. This event marked a turning point in Pohnpenesian history, as the country began to undergo significant political and social transformation. Author and historian, Mahino Watai describes the scene in the 2009 Book "To Kill 2 Birds". | ||

<poem>''The collapse of the Vahinà was marked by a series of violent clashes and brutal massacres in the late 1970s. Dozens of Vahinà elites were targeted and brutally murdered, and their homes and properties were destroyed in what was seen as a populist uprising against the privileged class. The violence was fueled by a deep-seated resentment and anger towards the Vahinà's wealth and power, which was perceived as unjust and exploitative. The massacres were a traumatic and tragic event in Pohnpenesian history, representing both the culmination of years of simmering tensions and the beginning of a new era in the country's political landscape.''</poem> | <poem>''The collapse of the Vahinà was marked by a series of violent clashes and brutal massacres in the late 1970s. Dozens of Vahinà elites were targeted and brutally murdered, and their homes and properties were destroyed in what was seen as a populist uprising against the privileged class. The violence was fueled by a deep-seated resentment and anger towards the Vahinà's wealth and power, which was perceived as unjust and exploitative. The massacres were a traumatic and tragic event in Pohnpenesian history, representing both the culmination of years of simmering tensions and the beginning of a new era in the country's political landscape.''</poem> | ||

| Line 244: | Line 245: | ||

In addition to the Vahinà, the wealthy class in Pohnpenesia were also targeted during the upheaval of the 1970s. Many saw the wealthy as the embodiment of the existing power structures that perpetuated inequality and sought to dismantle their influence. As a result, many wealthy individuals and families were subjected to harassment, threats, and violence. Some were forced to flee the country or give up their wealth and assets to avoid retribution. | In addition to the Vahinà, the wealthy class in Pohnpenesia were also targeted during the upheaval of the 1970s. Many saw the wealthy as the embodiment of the existing power structures that perpetuated inequality and sought to dismantle their influence. As a result, many wealthy individuals and families were subjected to harassment, threats, and violence. Some were forced to flee the country or give up their wealth and assets to avoid retribution. | ||

While the E.C. movement aimed to bring about social justice and equality, its policies had severely negative economic and societal consequences. The government's expropriation of land and nationalization of industries, intended to redistribute wealth and resources, led to a decline in production and economic stagnation. The lack of incentives for private investment and entrepreneurship discouraged economic growth and innovation, resulting in a shortage of goods and services, high inflation rates, and a shrinking job market. Additionally, the government's control over media and the suppression of dissenting opinions led to a lack of freedom of speech and civil liberties, creating a climate of fear and political instability. The E.C.'s policies also led to a brain drain, as thousands of professionals and educated individuals left the country in search of better opportunities and greater freedom. | While the E.C. movement aimed to bring about social justice and equality, its policies had severely negative economic and societal consequences. The government's expropriation of land and nationalization of industries, intended to redistribute wealth and resources, led to a decline in production and economic stagnation. The lack of incentives for private investment and entrepreneurship discouraged economic growth and innovation, resulting in a shortage of goods and services, high inflation rates, and a shrinking job market. Additionally, the government's control over media and the suppression of dissenting opinions led to a lack of freedom of speech and civil liberties, creating a climate of fear and political instability. The E.C.'s policies also led to a brain drain, as thousands of professionals and educated individuals left the country in search of better opportunities and greater freedom. The banks and financial corporations that once helped to stabilize the economy either left or liquified their stocks due to restrictive policies, effectively ending the industry. | ||

====Recognition of independence in foreign relations & the economic crisis ==== | |||

==== Recognition of independence in foreign relations & the economic crisis ==== | In the 1980s, Pohnpenesia plummeted into a severe economic crisis due to the turmoil caused by the E.C. regime. The neglect of infrastructure, severely underfunded education and healthcare, and ongoing political instability had taken a significant toll on the country's development. Due to the deserted finance and banking sector, Pohnpenesia's economy began to shift to agrarianism, and many people began working in subsistence farming, which was not enough to sustain the population. The country was also heavily dependent on foreign aid, which was often tied to political conditions and had a limited impact on the country's overall economic growth. [[File:Pohnpenesian slum.jpg|250px|thumb|Photo of Dargiletown, one of the many informal settlements of Harpan, located on the rural outskirts of the city. The settlement was demolished in 1993. circa. 1983]] | ||

In the 1980s, Pohnpenesia plummeted into a severe economic crisis due to the turmoil caused by the E.C. regime | |||

The grant of independence in foreign relations and diplomacy by the Riamese Federation in 1988 had significant economic and diplomatic implications for Pohnpenesia. With full autonomy in its foreign policy, Pohnpenesia was able to establish diplomatic relationships with other countries around the world, which opened up new avenues for trade and economic cooperation. This allowed the country to diversify its economic portfolio and reduce its dependence on the Riamese Federation, which had previously been its main trading partner. | The grant of independence in foreign relations and diplomacy by the Riamese Federation in 1988 had significant economic and diplomatic implications for Pohnpenesia. With full autonomy in its foreign policy, Pohnpenesia was able to establish diplomatic relationships with other countries around the world, which opened up new avenues for trade and economic cooperation. This allowed the country to diversify its economic portfolio and reduce its dependence on the Riamese Federation, which had previously been its main trading partner. | ||

Moreover, Pohnpenesia was able to participate more actively in international forums and organizations. As a result, the country was able to gain greater recognition and respect on the global stage, which opened up new opportunities for diplomatic and economic cooperation. Pohnpenesia was also able to use its newfound freedom to pursue policies that aligned with its own interests, rather than being bound by the constraints of the Riamese Federation. This enabled the country to take a more assertive role in shaping its own foreign policy agenda and advocating for its interests on the global stage. | Moreover, Pohnpenesia was able to participate more actively in international forums and organizations. As a result, the country was able to gain greater recognition and respect on the global stage, which opened up new opportunities for diplomatic and economic cooperation. Pohnpenesia was also able to use its newfound freedom to pursue policies that aligned with its own interests, rather than being bound by the constraints of the Riamese Federation. This enabled the country to take a more assertive role in shaping its own foreign policy agenda and advocating for its interests on the global stage. | ||

==== Recovery ==== | ====Recovery==== | ||

Following Pohnpenesia's recognition in foreign relations and the subsequent lifting of trade and investment barriers, the country's economy experienced a turnaround. The government, while still under the reign of the E.C, implemented experimental policies aimed at attracting foreign investment and slightly encouraging private enterprise, leading to a surge in job creation and economic growth. This | Following Pohnpenesia's recognition in foreign relations and the subsequent lifting of trade and investment barriers, the country's economy experienced a turnaround. The government, while still under the reign of the E.C, implemented experimental policies aimed at attracting foreign investment and slightly encouraging private enterprise, leading to a slight surge in job creation and economic growth. This allowed Pohnpenesia to increase its exports and diversify its economy. | ||

The country's newfound position in the global community also allowed it to secure aid and loans from international organizations and foreign governments. This helped the government to invest in infrastructure, education, and healthcare, providing a foundation for sustainable economic development. As a result, Pohnpenesia was able to reduce poverty and improve living standards for its citizens, as well as enhance its international reputation and strengthen its diplomatic ties with other nations. | The country's newfound position in the global community also allowed it to secure aid and loans from international organizations and foreign governments. This helped the government to invest in infrastructure, education, and healthcare, providing a foundation for sustainable economic development. As a result, Pohnpenesia was able to reduce the poverty rate from 53% in 1979 to 42% in 1989 and improve living standards for its citizens, as well as enhance its international reputation and strengthen its diplomatic ties with other nations. | ||

Despite the economic recovery, Pohnpenesia's economy remained heavily equalitarian, with a recent focus on community ownership and distribution of natural resources. This fixated ideology presented significant challenges for economic growth and development. Localized private investment was still discouraged, and the lack of a clear legal framework for private property rights made it difficult for businesses to thrive. The government's policies continued to prioritize the distribution of resources over private enterprise even through foreign policies, limiting the country's potential for economic growth. | Despite the economic recovery, Pohnpenesia's economy remained heavily equalitarian, with a recent focus on community ownership and distribution of natural resources. This fixated ideology presented significant challenges for economic growth and development. Localized private investment was still discouraged, and the lack of a clear legal framework for private property rights made it difficult for businesses to thrive. The government's policies continued to prioritize the distribution of resources over private enterprise even through foreign policies, limiting the country's potential for economic growth. | ||

=== 1990s === | ====1990s==== | ||

In the 1990s, Pohnpenesia continued to experience significant economic growth, albeit with some challenges. The government implemented several policies aimed at promoting trade and investment, including the establishment of export processing zones and the liberalization of certain sectors of the economy. These efforts paid off, as foreign investment continued to flow into the country, leading to the creation of new jobs and the expansion of export industries. | In the 1990s, Pohnpenesia continued to experience significant economic growth, albeit with some challenges. The government implemented several policies aimed at promoting trade and investment, including the establishment of export processing zones and the liberalization of certain sectors of the economy. These efforts paid off, as foreign investment continued to flow into the country, leading to the creation of new jobs and the expansion of export industries. | ||

| Line 266: | Line 266: | ||

Furthermore, the country faced challenges related to governance and corruption, which hindered its development. The government was often criticized for its lack of transparency and accountability, and allegations of corruption were widespread. This undermined the country's reputation and made it harder to attract foreign investment. Nevertheless, Pohnpenesia continued to make progress in its economic development. | Furthermore, the country faced challenges related to governance and corruption, which hindered its development. The government was often criticized for its lack of transparency and accountability, and allegations of corruption were widespread. This undermined the country's reputation and made it harder to attract foreign investment. Nevertheless, Pohnpenesia continued to make progress in its economic development. | ||

In an attempt to legitimize their control over Pohnpenesia, the Riamese government held a referendum on the issue of independence on May 30, 1991. However, this referendum was widely regarded as rigged and unfair, with allegations of voter intimidation and ballot tampering. The results of the referendum indicated that the majority of the population favored remaining under Riamese control, but many in Pohnpenesia and the international community questioned the legitimacy of these results. Despite these setbacks, the movement for independence in Pohnpenesia continued to persist throughout the decade | In an attempt to legitimize their control over Pohnpenesia, the Riamese government held a referendum on the issue of independence on May 30, 1991. However, this referendum was widely regarded as rigged and unfair, with allegations of voter intimidation and ballot tampering. The results of the referendum indicated that the majority of the population favored remaining under Riamese control, but many in Pohnpenesia and the international community questioned the legitimacy of these results. Despite these setbacks, the movement for independence in Pohnpenesia continued to persist throughout the decade, before staling due to political crackdowns on dissents in the Pohnpenesian government. | ||

[[File:Pohnpenesian 90 protests.png|thumb|A demonstration against the National Independence Referendum results, circa. 1991]] | [[File:Pohnpenesian 90 protests.png|thumb|A demonstration against the National Independence Referendum results, circa. 1991]] | ||

===21st century=== | |||

At the turn of the 21st century, Pohnpenesia continued to grapple with political and economic challenges, despite improvements in diplomatic relations and the economy. The E.CS and its socialist policies had left the economy stagnant for most of the 20th century. The government's focus on equality had often come at the expense of individual freedoms and rights, leading to criticism from human rights organizations and some foreign governments. | |||

====2000s==== | |||

In the early 2000s, Pohnpenesia was also dealing with the aftermath of the assassination of Tuhinga Rama, the country's former Prime Minister and the leader of the E.C. movement. His death had caused political instability and raised concerns about the country's future. | |||

=== 21st century === | |||

At the turn of the 21st century, Pohnpenesia continued to grapple with political and economic challenges, despite | |||

==== 2000s ==== | |||

In the early 2000s, Pohnpenesia was also dealing with the aftermath of the assassination of Tuhinga Rama, the country's former Prime Minister and the leader of the E.C. movement. His death had caused political instability and raised concerns about the country's future | |||

A growing resentment towards the E.C. government began to emerge among some sectors of Pohnpenesian society. Public views begin to see the E.C. as a corrupt and authoritarian regime, with little regard for individual rights and freedoms. These sentiments were fueled by reports of human rights abuses, including the suppression of political opposition and the media, and the use of violence against peaceful protesters. Despite these criticisms, the E.C. government maintained its grip on power, and tensions between the ruling party and its opponents continued to simmer throughout this period. The reputation of the E.C. was further intensified by the torture and execution of Ava Alexandretta, a prominent Pohnpenesian human rights advocate. Alexandretta was a vocal critic of the E.C. government's authoritarian policies and was known for her efforts to expose human rights abuses committed by the regime. In 2003, she was arrested and charged with sedition and terrorism, allegations that were widely believed to be politically motivated. During her detention, Alexandretta was subjected to torture and other forms of mistreatment, which led to her deteriorating health. Despite pleas from domestic and international human rights groups for her release and medical treatment, Alexandretta was executed in 2004. Her death sparked widespread condemnation and protests against the E.C. government's human rights record, further fueling public resentment towards the ruling party. | A growing resentment towards the E.C. government began to emerge among some sectors of Pohnpenesian society. Public views begin to see the E.C. as a corrupt and authoritarian regime, with little regard for individual rights and freedoms. These sentiments were fueled by reports of human rights abuses, including the suppression of political opposition and the media, and the use of violence against peaceful protesters. Despite these criticisms, the E.C. government maintained its grip on power, and tensions between the ruling party and its opponents continued to simmer throughout this period. The reputation of the E.C. was further intensified by the torture and execution of Ava Alexandretta, a prominent Pohnpenesian human rights advocate. Alexandretta was a vocal critic of the E.C. government's authoritarian policies and was known for her efforts to expose human rights abuses committed by the regime. In 2003, she was arrested and charged with sedition and terrorism, allegations that were widely believed to be politically motivated. During her detention, Alexandretta was subjected to torture and other forms of mistreatment, which led to her deteriorating health. Despite pleas from domestic and international human rights groups for her release and medical treatment, Alexandretta was executed in 2004. Her death sparked widespread condemnation and protests against the E.C. government's human rights record, further fueling public resentment towards the ruling party. | ||

| Line 288: | Line 281: | ||

The existing challenges resulted in the escalation of opposition against the E.C. government, with calls for democratic reform and greater transparency becoming more frequent. Demonstrations and protests against the ruling party became more common, often met with violent suppression from security forces. In 2008, a series of protests sparked by the government's decision to sell off public land resulted in clashes with police and widespread arrests, further stoking public anger. Despite the growing opposition, the E.C. government persisted in power, relying on its control of the media and security forces to repress dissent and maintain its hold on the nation. | The existing challenges resulted in the escalation of opposition against the E.C. government, with calls for democratic reform and greater transparency becoming more frequent. Demonstrations and protests against the ruling party became more common, often met with violent suppression from security forces. In 2008, a series of protests sparked by the government's decision to sell off public land resulted in clashes with police and widespread arrests, further stoking public anger. Despite the growing opposition, the E.C. government persisted in power, relying on its control of the media and security forces to repress dissent and maintain its hold on the nation. | ||

In 2009, Pohnpenesia was struck by the Semaine Noire tsunami, | In 2009, Pohnpenesia was struck by the Semaine Noire tsunami, that devastated the southern coasts of the country. The tsunami, which was triggered by intense seismic activity in the Kaldaic Ocean, caused widespread destruction, killing an estimated 15,200 people and displacing tens of thousands more. The city of Porti-Herena was among the hardest hit, with almost 98% of its buildings and infrastructure destroyed by the massive waves. The disaster had a profound impact on the country, exacerbating its already precarious economic and social conditions and requiring a massive humanitarian response from both the government and the international community. The E.C. government's inability to effectively respond to the Semaine Noire tsunami further eroded its already weakened legitimacy. The government's slow and inadequate response to the disaster, coupled with its overall failure to address the country's underlying problems, fueled public anger and frustration. The disaster highlighted the extent to which the E.C. had failed to provide even basic services and infrastructure to its citizens, and served as a catalyst for renewed calls for democratic reform and change. | ||

[[File:Porti Herena Tsunami.jpeg|200px|thumb|left|La Rue de la Reine after Semaine Noire, circa. 2009.]] | [[File:Porti Herena Tsunami.jpeg|200px|thumb|left|La Rue de la Reine after Semaine Noire, circa. 2009.]] | ||

==== 2010s ==== | ====2010s==== | ||

At the start of the 2010s, the government of Pohnpenesia began to fully prioritize economic development and social welfare programs to improve the living standards of citizens, though progress remained slow and uneven. High rates of poverty, unemployment, and inequality persisted, with basic necessities such as healthcare still difficult to access for many. The E.C responded to growing pressure for reform by opening up the country to greater international trade and investment. The government's efforts included relaxing restrictions on the media and opposition parties and increasing accountability for human rights abuses. The country saw progress in economic growth, as well as in social welfare programs and infrastructure development, which created new job opportunities and improved access to education and healthcare. These measures led to a prosperous increase in living standards and a reduction in poverty rates. Despite socioeconomic improvements, Pohnpenesia continued to face significant challenges in achieving political stability, and the party had failed to mend its fundamental flaws. | |||

At the start of the 2010s, the government of Pohnpenesia began to prioritize economic development and social welfare programs to improve the living standards of citizens, though progress remained slow and uneven. High rates of poverty, unemployment, and inequality persisted, with basic necessities such as healthcare and education | =====2010 Protests===== | ||

In 2010, a wave of massive protests erupted across Pohnpenesia. The protests were largely violent and were led by a coalition of civil society groups, political parties, and ordinary citizens. Demonstrators called for a range of reforms, including greater transparency and accountability, an end to police brutality, and the release of political prisoners. | |||

The protests had a profound impact on Pohnpenesian society, leading to a significant shift in public discourse and political consciousness. They brought to the forefront long-standing grievances and frustrations that had been simmering beneath the surface for years, and galvanized a new generation of activists and social movements. The protests also highlighted the country's deep social and economic divisions, as well as the persistence of authoritarianism and corruption within the political establishment. Despite their initial impact, however, the protests ultimately failed to bring about the systemic change that many had hoped for. The government responded to the demonstrations with repression and violence, including the use of tear gas, rubber bullets, and live ammunition against peaceful protesters. Many activists and journalists were arrested or subjected to harassment and intimidation, and the government cracked down on social media and other forms of online communication. | |||

=====New Pohnpenesia Plan===== | |||

From 2010 to 2014, Pohnpenesia embarked on a comprehensive urban renewal program known as the New Pohnpenesia Plan. Despite facing political instability and a precarious economic situation, the government carried a great commitment to implementing the program, which was spearheaded by Riamese funding aid and overseen by the economic minister, Jean Makaiote. | |||

{{multiple image | |||

| width = 150 | |||

| image1 = Harpan slum clearance (1998).png | |||

| alt1 = | |||

| image2 = Medines apartment high rise.jpeg | |||

| alt2 = | |||

| footer = Throughout the 2010s, the N.P.P program demolished the vast majority of informal settlements in Pohnpenesia and replaced them with modern housing units. An example is the Luakimar neighborhood, an informal neighborhood in Medines being cleared away to create over 30 mid-rise apartments. | |||

}} | |||

The primary objective of the New Pohnpenesia Plan was to address the pressing challenges of urban slums, inadequate sanitation, and insufficient infrastructure throughout the country. To achieve this, the program focused on the mass-demolition of slums and the subsequent construction of new housing projects, with the aim of improving the living conditions of marginalized communities and providing safer and more habitable environments. Emphasizing the significance of proper waste management and hygiene practices for public health, the program also prioritized the enhancement of urban cities' sanitation systems. | |||

Significant investments were allocated to infrastructure development, including the construction of roads, bridges, and other essential amenities. These endeavors aimed to enhance connectivity, accessibility, and the overall functionality of urban areas. Additionally, the government sought to stimulate economic growth and enhance the living standards of the population by creating employment opportunities through these projects. | |||

The ambitious scope of the New Pohnpenesia Plan presented considerable challenges, given the limited financial resources and the complex nature of urban development. The program persisted even amidst the height of political instability, though it faced difficulties in fully meeting its objectives within the specified timeframe due to the rapid pace of urbanization and the scale of required interventions. Moreover, the program attracted criticism for the displacement of residents caused by the demolition of slums. | |||

The | The New Pohnpenesia Plan achieved significant progress in addressing the challenges of urban renewal in the country. Despite political instability and economic difficulties, the program persisted and made notable achievements in improving the living conditions of marginalized communities, enhancing public health, and promoting economic growth. According to official statistics, the program resulted in the demolition of the vast majority of informal units, and the construction of over 150,000 new housing units according to the E.C. Additionally, the program improved the sanitation systems of over 100 settlements, both rural and urban, and created over 50,000 new jobs. Due to this, informal settlements were effectively eradicated from the nation and transformed cityscapes by 2014. | ||

===== Post-Equalitarian ===== | =====Post-Equalitarian and the Vevessi Riots===== | ||

On January 15, 2015, the E.C. government dissolved, marking the end of an era for Pohnpenesia. The decision to dissolve was made in response to the widespread protests and international pressure for democratic reforms, which had been mounting for several years. However, the transition to a new political system was far from smooth. In the aftermath of the dissolution, violent clashes between government forces and opposition groups, massive riots, and localized conflicts across the archipelago began⏤known as the ''Vevessi'' (lit. 'chaos' in Pohnpenesian). According to Paix-Internationalé, over 100,000 civilians in the country were displaced, and infrastructure damage reached to the billions. Damages in Harpan alone were estimated to exceed 4 billion ACU, prompting the deployment of Riamese National Guards to suppress the riots. In the midst of the chaos, a transitional council emerged, tasked with navigating the nation through the turbulent transition period towards establishing a new system. The riots ended on February 12th following the signing of a decree appointing Charles d'Vonte as the first president in the post-E.C. era. | |||

[[File:Pohnpenesia riots 2015.png|300px|thumb|right|A massive riot in the Chuo En (Central Circle) District, Harpan.]] | |||

====Recovery==== | |||

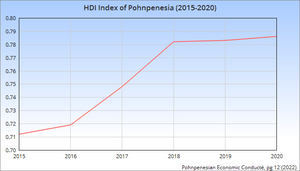

[[File:Pohnpenesia HDI Index from (2015-2020).png|300px|thumb|left|Pohnpenesia's growth in living standards by H.D.I from 2015 to 2020.]] | |||

After instability settled, Pohnpenesia experienced a substantial revival in its living standards and economy following the fall of the Equalitarian Communion. This transformative period was marked by significant progress and improvements in various socio-economic indicators. One key measure of progress was the notable increase in Pohnpenesia's Human Development Index (HDI), which saw a growth of 10.39% from 0.712 to 0.795. | |||

The revival of Pohnpenesia's economy was equally impressive, with a substantial increase in the country's GDP output. Over the course of five years, Pohnpenesia witnessed an impressive growth rate of 38.10%. This economic expansion was fueled by a range of strategies and tactics employed by the government to stimulate growth and attract investment. These measures included the implementation of favorable economic policies, the creation of business-friendly environments, and the promotion of entrepreneurship and innovation. | |||

== Geography == | The positive impact of Pohnpenesia's economic revival was also reflected in a significant reduction in the poverty rate. Over the course of the five-year period, the poverty rate dropped from 22% to 4%, a considerable improvement in the standard of living for a large segment of the population. This reduction in poverty was achieved through targeted social welfare programs, job creation initiatives, and investments in education and healthcare. | ||

The revival of Pohnpenesia's economy and the improvement in living standards were accompanied by a comprehensive overhaul of the policies and laws that were previously associated with the Equalitarian Communion. Many of the restrictive measures and regulations implemented during that era were removed entirely, fostering a more open and competitive economic environment. However, certain aspects of the Equalitarian economy, such as the Universal Basic Income and centralization, were retained, albeit with potential modifications and adjustments to align with the changing socio-economic landscape. | |||

In 2016, a series of new reformatory bills, collectively the 'Cekoro Act' were passed by the Keuva. The bills focused on re-structuring the administration, including transforming the country from a federal nation to a regional nation composed of 4 administrative regions (bumen). Beforehand, each island was a federal subject and yielded administrative powers. | |||

==Geography== | |||