Suhalan language: Difference between revisions

(Created page with "{{Region icon Kylaris}} {{Infobox language | name = Suhalan | altname = | nativename = ''Limba Suxaranu'' | acceptance = | image =...") |

m (→Personal Pronouns: Fixed incorrect colspan.) |

||

| (23 intermediate revisions by 3 users not shown) | |||

| Line 1: | Line 1: | ||

{{ | {{KylarisRecognitionArticle}} | ||

{{Infobox language | {{Infobox language | ||

| name = Suhalan | | name = Suhalan | ||

| Line 85: | Line 85: | ||

| lingua_ref = | | lingua_ref = | ||

| ietf = | | ietf = | ||

| map = | | map = [[File:SuhalanLangMap.png]] | ||

| mapsize = | | mapsize = | ||

| mapalt = | | mapalt = | ||

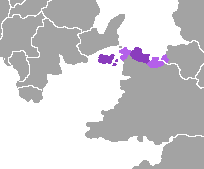

| mapcaption = | | mapcaption = {{legend|#8a3cbd|Countries or regions where Suhalan is an official language}} {{legend|#b460ea|Regions where Suhalan is spoken but is not recognized as an official language}} | ||

| map2 = | | map2 = | ||

| mapalt2 = | | mapalt2 = | ||

| Line 107: | Line 107: | ||

==History== | ==History== | ||

Suhalan is a {{wp|Romance languages|Solarian language}}, descending from {{wp|Latin|Solarian}}. Solarian was adopted relatively late into the Solarian period, and modern Suhalan possesses significant substrate influence from !Punic, with Suxaro-Suhalan having influence from | Suhalan is a {{wp|Romance languages|Solarian language}}, descending from {{wp|Latin|Solarian}}. Solarian was adopted relatively late into the Solarian period, and modern Suhalan possesses significant substrate influence from !Punic, with Suxaro-Suhalan having influence from {{wp|Paleo-Sardinian language|Paleo-Suhalan}}. All varieties of Suhalan have adstratum influence from {{wp|French language|Gaullican}}, {{wp|Arabic language|Rahelian}}, and {{wp|Persian language|Pardari}} with Tsabaro-Suhalan having more Gaullican influence in addition to influence. Suxaro-Suhalan holds significant {{wp|Italian language|Vespasian}} influence, especially on the western side of the island. | ||

===Solarian Period=== | ===Solarian Period=== | ||

Solarian was introduced to the Island around 113 BCE, when the island was first invaded by Solarian forces. {{wp|Punic language|Nimenese}} and {{wp|Paleo-Sardinian language|Paleo-Suhalan}} were the most spoken languages prior to this, with Nimenese being prevalent on the south and eastern coasts. Some {{wp|greek language|Piraean}} influence also existed on the west coast. The Island was slow to adopt Solarian, and its pre-existing languages stayed strong for centuries after its conquest, leading to the mockery of its inhabitants by Solarian writers who deemed them 'uncivilized'. Nevertheless, Solarian grew and by the 4th century BCE it was the majority language of the Island, with other languages relegated to secondary status in the centre and southern coast. | Solarian was introduced to the Island around 113 BCE, when the island was first invaded by Solarian forces. {{wp|Punic language|Nimenese}} and {{wp|Paleo-Sardinian language|Paleo-Suhalan}} were the most spoken languages prior to this, with Nimenese being prevalent on the south and eastern coasts. Some {{wp|greek language|Piraean}} influence also existed on the west coast. The Island was slow to adopt Solarian, and its pre-existing languages stayed strong for centuries after its conquest, leading to the mockery of its inhabitants by Solarian writers who deemed them 'uncivilized'. Nevertheless, Solarian grew and by the 4th century BCE it was the majority language of the Island, with other languages relegated to secondary status in the centre and southern coast. | ||

The Solarian of Suhala stayed much closer to Classical Solarian for much longer than other dialects, undergoing less sound changes and keeping more grammatical features, partially due to its distance from the rest of Euclea and periods of de facto self-governance. Eventually | The Solarian of Suhala stayed much closer to Classical Solarian for much longer than other dialects, undergoing less sound changes and keeping more grammatical features, partially due to its distance from the rest of Euclea and periods of de facto self-governance. Eventually Old Suhalan had become distinct enough from Vulgar Solarian to be considered its own language by modern linguists, although there is little consensus on when this split happened, with timescales of between the 10th to the mid-12th century having been proposed. Old Suhalan was marked by a simplification of the {{wp|Grammatical case|case system}} into a {{wp|nominative case|nominative}}-{{wp|accusative case|accusative}}, a {{wp|genitive case|genitive}}, and a {{wp|dative case|dative}} which took over the functions of the Solarian {{wp|locative case|locative}} and {{wp|ablative case|ablative}}. Old Suhalan also possessed a {{wp|Word order|freer word order}} and less {{wp|loanword|loanwords}} than its contemporary Solarian languages, with the main {{wp|adstratum(linguistics|superstrate}} influences from Rahelian, Pardari, and Gaullican being unevenly distributed across the island. | ||

Old Suhalan was the primary language for internal administration, commerce, and literature, meaning that a large corpus is available. Solarian was largely used only for external communication with states in Euclea, and the Old Suhalan language held a markedly more prestigious position in Medieval Suhala than its contemporaries did in their respective areas. The earliest works in Suhalan are the [[Nepitagara Documents]] and the [[Sermons of St. Simjone]], with Suhalan literature tracing its origins to the mid-12th century focusing on accounts of the lives of saints, rulers, or folk heroes, such as the [[Song of Nebidu|Kanșode de Nepito]]. | Old Suhalan was the primary language for internal administration, commerce, and literature, meaning that a large corpus is available. Solarian was largely used only for external communication with states in Euclea, and the Old Suhalan language held a markedly more prestigious position in Medieval Suhala than its contemporaries did in their respective areas. The earliest works in Suhalan are the [[Nepitagara Documents]] and the [[Sermons of St. Simjone]], with Suhalan literature tracing its origins to the mid-12th century focusing on accounts of the lives of saints, rulers, or folk heroes, such as the [[Song of Nebidu|Kanșode de Nepito]]. | ||

After the Povelian invasion of the western side of the island, the use of Suhalan as an administrative gradually declined as more and more local documents were written in Povelian. The Suhalan on the west side of the island also underwent significant influence from Povelian, adopting many of its spelling conventions and loaning many words. Suhalan on the east side, by contrast, took in far fewer loanwords. Futher dialectical differences would emerge, with Coian Suhalan, Central Suhalan, West Suhalan, and East Suhalan becoming more distinct in their phonologies and lexicons. The earliest examination of Suhalan from a linguistic perspective would be done by !Dante, defining it as an ''eia'' language, and noting that it ''Displays 3 vulgar languages'', and remarking that Suhala's geographic qualities were the likely cause. Later Suhalan-focused analysis would mostly come in the 16 and 1700s, from both Povelian and Suhalan intellectuals. | After the Povelian invasion of the western side of the island, the use of Suhalan as an administrative gradually declined as more and more local documents were written in Povelian. The Suhalan on the west side of the island also underwent significant influence from Povelian, adopting many of its spelling conventions and loaning many words. Suhalan on the east side, by contrast, took in far fewer loanwords. Futher dialectical differences would emerge, with Coian Suhalan, Central Suhalan, West Suhalan, and East Suhalan becoming more distinct in their phonologies and lexicons. The earliest examination of Suhalan from a linguistic perspective would be done by !Dante, defining it as an ''eia'' language, and noting that it "''Displays 3 vulgar languages''", and remarking that Suhala's geographic qualities were the likely cause. Later Suhalan-focused analysis would mostly come in the 16 and 1700s, from both Povelian and Suhalan intellectuals. | ||

===Modern Suhalan=== | ===Modern Suhalan=== | ||

| Line 124: | Line 124: | ||

In 1885, the first comprehensive grammar of Suhalan was published by Suhalan writer [[Gafrieje of Sethare|Gafrieje Ardasu Sartore de Seśari]], named ''Unu Anajusu Compjeśu des Limba Suxaranu'', or "A Comprehensive Analysis of the Suhalan Language". Gafrieje would write other major works of Suhalan literature, including ''[[The Blood-Red Raven of Ajambasai|Su Korvu Rubru Sanqbine d'Ajambasaj ]]''("The Blood-Red Raven") and ''[[Emesis Blue|Laglva Emesu]]''("Emesis Blue"). His work, as well as the work of a few other Suhalan writers, managed to gain recognition for the Suhalan language, which was acknowledged as a regional language of Etruria in 1901. | In 1885, the first comprehensive grammar of Suhalan was published by Suhalan writer [[Gafrieje of Sethare|Gafrieje Ardasu Sartore de Seśari]], named ''Unu Anajusu Compjeśu des Limba Suxaranu'', or "A Comprehensive Analysis of the Suhalan Language". Gafrieje would write other major works of Suhalan literature, including ''[[The Blood-Red Raven of Ajambasai|Su Korvu Rubru Sanqbine d'Ajambasaj ]]''("The Blood-Red Raven") and ''[[Emesis Blue|Laglva Emesu]]''("Emesis Blue"). His work, as well as the work of a few other Suhalan writers, managed to gain recognition for the Suhalan language, which was acknowledged as a regional language of Etruria in 1901. | ||

Suhalan achieved a brief moment of popularity after the [[Great War (Kylaris)|Great War]], with the work of Suhalan-language poets, writers, and intellectuals being widely consumed. This came to a crashing halt with the rise of the [[National Solarianism|National-Solarians]], who suspected Suhalans of harboring councilist and secessionist sympathies, and who supported the [[Etrurianization]] of Suhala. Etrurianization involved the favoring of Etrurian groups in Suhala, whose numbers swelled, and had a devastating effect on the public use of the Suhalan language. Use of Suhalan in public was criminalized, and children who spoke in it during school would be beaten. These efforts lead to the Suhalan liberation movements adopting the defense of the Suhalan language as one of their main goals, and | Suhalan achieved a brief moment of popularity after the [[Great War (Kylaris)|Great War]], with the work of Suhalan-language poets, writers, and intellectuals being widely consumed. This came to a crashing halt with the rise of the [[National Solarianism|National-Solarians]], who suspected Suhalans of harboring councilist and secessionist sympathies, and who supported the [[Etrurianization]] of Suhala. Etrurianization involved the favoring of Etrurian groups in Suhala, whose numbers swelled, and had a devastating effect on the public use of the Suhalan language. Use of Suhalan in public was criminalized, and children who spoke in it during school would be beaten. These efforts lead to the Suhalan liberation movements adopting the defense of the Suhalan language as one of their main goals, with the [[National Front for the Fatherland and Unity|Fronte Naşonaje bro su Padria et Konkorśa]] publishing their seminal pamphlet [[Saje Ajexe|"Saje Ajexe - Finoas Rebiteto!"]] ("Peace be Unto You - Until the Reseeing"), railing against the supression of Suhala. Many works of Suhalan literature were smuggled out of the island into temporary safe havens in nearby countries. Many Suhalans left the country between the Great War and the Solarian War, and strengthened Suhalan communities in Eastern [[Euclea]] and the [[Asterias]], with a significant Suhalan-language community developing in Eldmark. | ||

After Suhalan independence, the language quickly became more used in everyday life, aided by the pro-Suhalan position of the new ruling parties and by the slow emigration out of the country by Etrurians. Suhalan became the national language of commerce and governance, and soon it replaced Vespasian in literature. Under the [[Red League of Suhala|Ligbe Rufra de Suxare]], a concerted policy of "[[De-Etrurianization]]" was implemented, with the creation of the [[National Academy of Suhalan|Axatemie Nașonaje Suxarano]] to regulate the Suhalan language and many Vespasian loanwords for technical field being replaced by ones loaned from Solarian, Gaullican, or calqued from Vespasian. Western Suhalan was also suppressed, being seen as having too much Vespasian influence, and the language underwent significant orthographic reform, removing instances of digraphs like ll and sc and standardizing the use of letters like Çç and Şş. This policy of De-Etrurianization was halted after the LRS regime was replaced, and nowadays Suhalan dialects recieve more support from the government. | After Suhalan independence, the language quickly became more used in everyday life, aided by the pro-Suhalan position of the new ruling parties and by the slow emigration out of the country by Etrurians. Suhalan became the national language of commerce and governance, and soon it replaced Vespasian in literature. Under the [[Red League of Suhala|Ligbe Rufra de Suxare]], a concerted policy of "[[De-Etrurianization]]" was implemented, with the creation of the [[National Academy of Suhalan|Axatemie Nașonaje Suxarano]] to regulate the Suhalan language and many Vespasian loanwords for technical field being replaced by ones loaned from Solarian, Gaullican, or calqued from Vespasian. Western Suhalan was also suppressed, being seen as having too much Vespasian influence, and the language underwent significant orthographic reform, removing instances of digraphs like ll and sc and standardizing the use of letters like Çç and Şş. This policy of De-Etrurianization was halted after the LRS regime was replaced, and nowadays Suhalan dialects recieve more support from the government. | ||

| Line 198: | Line 198: | ||

| | | | ||

| {{IPA link|l}} / {{IPA link|ɹ}} | | {{IPA link|l}} / {{IPA link|ɹ}} | ||

| {{IPA link|j}} | | {{IPA link|j}} / {{IPA link|j̃}} | ||

| | | | ||

| {{IPA link|w}} | | {{IPA link|w}} | ||

| Line 212: | Line 212: | ||

* Central Suhalan dialects replace the phonemes /k͡p/ and /ɡ͡b/ with /ʍ/ and /w/ respectively | * Central Suhalan dialects replace the phonemes /k͡p/ and /ɡ͡b/ with /ʍ/ and /w/ respectively | ||

* Many younger speakers of Central Suhalan dialects, due to {{wp|hypercorrection}}, often replace instances of [w] with [ɡ͡b] in situations where [w] would be correct in Standard Suhalan, i.e Standard Suhalan ''Vicljom'' becomes ''Qbicljom'' | * Many younger speakers of Central Suhalan dialects, due to {{wp|hypercorrection}}, often replace instances of [w] with [ɡ͡b] in situations where [w] would be correct in Standard Suhalan, i.e Standard Suhalan ''Vicljom'' becomes ''Qbicljom'' | ||

* Many speakers of Central Suhalan dialects hypercorrect /l/ into /j/ in situations where the former would be correct in Standard Suhalan, i.e Standard Suhalan '' | * Many speakers of Central Suhalan dialects hypercorrect /l/ into /j/ in situations where the former would be correct in Standard Suhalan, i.e Standard Suhalan ''Limba'' (Languge) and ''Falsu'' (Deceptive, Sneaky) becoming ''Jimba'' and ''Fajsu'' | ||

* In the Northwest Suhalan dialect, /d͡ʒ/ is realized as [ʎ], likely due to influence from Vespasian. | * In the Northwest Suhalan dialect, /d͡ʒ/ is realized as [ʎ], likely due to influence from Vespasian. | ||

| Line 245: | Line 245: | ||

===Orthography=== | ===Orthography=== | ||

Suhalan uses the {{wp|Latin alphabet|Solarian alphabet}}, with 5 vowel letters (along with an acute diacritic to distinguish {{wp|Homophony|homophones}}, and | Suhalan uses the {{wp|Latin alphabet|Solarian alphabet}}, with 5 vowel letters (along with an acute diacritic to distinguish {{wp|Homophony|homophones}}, and 24 consonant letters. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

! | ! width="10px" | Suhalan Letter || width="10px" | Suhalan Name || width="10px" | IPA sound || width="20px" | Notes | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Aa || | | Aa || A || {{IPA link|a}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Bb || | | Bb || Be || {{IPA link|b}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Cc || | | Cc || Ce || {{IPA link|k}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

|Çç || Çe || {{IPA link|tʃ}} | |Çç || Çe || {{IPA link|tʃ}} || Represents {{IPA link|dʒ}} in Coio-Suhalan | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Dç dç || Adçe || {{IPA link|dʒ}} || Represents {{IPA link|dð}} in Coio-Suhalan | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |Dd || De || {{IPA link|d̪}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |Ee || Ej || {{IPA link|ɛ}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |Ff || Ef || {{IPA link|f}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |Gg || Ge || {{IPA link|g}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |Ii || I || {{IPA link|i}}, {{IPA link|j}}* || Represents the semivowel {{IPA link|j}} when before a vowel | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | |Jj || Je || {{IPA link|j}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Kk || Kab || {{IPA link|k}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Ll || El || {{IPA link|l}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Gl, gl || Egle || {{IPA link|dʒ}} ,{{IPA link|ʃ}} || Represents {{IPA link|dʒ}} word-initially and {{IPA link|ʃ}} intervocalically. Represents {{IPA link|ʎ}} in Northwest Suhalan and word-initially in Central Suhalan, {{IPA link|ð}} in Coio-Suhalan, and {{IPA link|ʒ}} intervocalically in Central Suhalan | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Mm || Eme || {{IPA link|m}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Nn || Ene || {{IPA link|n}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Oo || O || {{IPA link|ɔ}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Pp || Pi || {{IPA link|p}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Qp, qp || Aqpa || {{IPA link|k͡p}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Qb, qb || Aqba || {{IPA link|ɡ͡b}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Rr || Are || {{IPA link|ɹ}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Ss || Es || {{IPA link|s}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Şş || Eşu || {{IPA link|ʃ}} || Represents {{IPA link|ʒ}} in Coio-Suhalan | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Śś || Śeśa || {{IPA link|θ}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Tt || Ta || {{IPA link|t}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Uu || U || {{IPA link|u}}, {{IPA link|w}} || Represents the semivowel {{IPA link|w}} when before a vowel | ||

|- | |- | ||

| | | Vv || Ve || {{IPA link|w}} || | ||

|- | |- | ||

| X || Exir || {{IPA link|x}} || | |||

|- | |||

| Z || Eze || {{IPA link|ʃ}} || Represents {{IPA link|ʒ}} in Central Suhalan and {{IPA link|ð}} in Coio-Suhalan | |||

|} | |} | ||

==Grammar== | ==Grammar== | ||

| Line 322: | Line 320: | ||

! rowspan="3" | {{wp|Grammatical case|case}} || colspan="8" | Number and person | ! rowspan="3" | {{wp|Grammatical case|case}} || colspan="8" | Number and person | ||

|- | |- | ||

! colspan=" | ! colspan="4" | Singular || colspan="4" | Plural | ||

|- | |- | ||

! 1st || 2nd || 3rd M. || 3rd F. || 1st || 2nd || 3rd M. || 3rd F. | ! 1st || 2nd || 3rd M. || 3rd F. || 1st || 2nd || 3rd M. || 3rd F. | ||

| Line 329: | Line 327: | ||

| Jo | | Jo | ||

| Tu | | Tu | ||

| | | Ide | ||

| | | Ida | ||

| Nor | | Nor | ||

| Bor | | Bor | ||

| | | Idi | ||

| | | Ider | ||

|- | |- | ||

! rowspan="1" | Accusative | ! rowspan="1" | Accusative | ||

| Me | | Me | ||

| Te | | Te | ||

| | | Idu | ||

| | | Ida | ||

| Ne | | Ne | ||

| Be | | Be | ||

| | | Idor | ||

| | | Idar | ||

|- | |- | ||

! rowspan="1" | Dative | ! rowspan="1" | Dative | ||

| Line 387: | Line 385: | ||

All nouns in Suhalan are either masculine or feminine, and the gender of a noun can usually be told from its ending. However, there are nouns which have a feminine ending and follow a feminine declension pattern but are masculine, and vice verse, leading to some ambiguous situations. Suhalan posesses two grammatical numbers, the singular and plural. It also has two grammatical cases, the Nominative and the Oblique. The nominative is used for the subjects and direct objects of verbs, while the oblique is used for nouns with prepositions or the indirect objects of verbs. Nouns can be grouped into declension patterns. | All nouns in Suhalan are either masculine or feminine, and the gender of a noun can usually be told from its ending. However, there are nouns which have a feminine ending and follow a feminine declension pattern but are masculine, and vice verse, leading to some ambiguous situations. Suhalan posesses two grammatical numbers, the singular and plural. It also has two grammatical cases, the Nominative and the Oblique. The nominative is used for the subjects and direct objects of verbs, while the oblique is used for nouns with prepositions or the indirect objects of verbs. Nouns can be grouped into declension patterns. | ||

====Femidina | ====Femidina==== | ||

Nouns in the Feminine | Nouns in the Feminine declension tend to come from the Latin 1st declension. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ "House" | |+ "House" | ||

| Line 406: | Line 404: | ||

|} | |} | ||

==== | ====Efixenu==== | ||

Nouns in the | Nouns in the Epicene declension tend to come from the Latin 3rd declension, and can be either masculine or feminine. | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|+ "Tree" | |+ "Tree" | ||

| Line 462: | Line 460: | ||

|- | |- | ||

|} | |} | ||

===Verbs=== | ===Verbs=== | ||

Verbs are highly inflected, and belong to one of three conjugation patterns classified by their infinitive endings, are, ere, and ire. Suhalan is traditionally regarded to have 4 tenses, the present ('' | Verbs are highly inflected, and belong to one of three conjugation patterns classified by their infinitive endings, are, ere, and ire. Suhalan is traditionally regarded to have 4 tenses, the present (''bresente''), preterite (''preśeriśu''), imperfect past (''imperfejśu''), and future (''fuśuru''), as well as 3 moods, the indicative (''indixaśibu'') , subjunctive (''supjunctibu''), and imperative (''imperaśibu''). | ||

====-are verbs==== | ====-are verbs==== | ||

| Line 486: | Line 485: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Future | | Future | ||

| ''Kant''-''' | | ''Kant''-'''arav''' || ''Kant''-'''arar''' || ''Kant''-'''aret''' || ''Kant''-'''aremor''' || ''Kant''-'''arajśir''' || ''Kant''-'''arent''' || I will sing | ||

|- | |- | ||

! rowspan="4" | Subjunctive | ! rowspan="4" | Subjunctive | ||

| Line 499: | Line 498: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Future | | Future | ||

| ''Kant''-''' | | ''Kant''-'''araj''' || ''Kant''-'''arïar''' || ''Kant''-'''arajat''' || ''Kant''-'''arajamor''' || ''Kant''-'''arajaśir''' || ''Kant''-'''ajant''' || If I will sing | ||

|- | |- | ||

! rowspan="1" | Imperative | ! rowspan="1" | Imperative | ||

| Line 617: | Line 616: | ||

{| class="wikitable" | {| class="wikitable" | ||

|- style="background:#efefef;" | |- style="background:#efefef;" | ||

| | |Estmerish||''Solarian''||'''''Suhalan'''''||''Etrurian''||''Esmeiran''||''Montecaran''||''Gaullican''||''Luzelese''||''Tosuton'' | ||

|- | |- | ||

|key | |key | ||

| Line 631: | Line 630: | ||

|night | |night | ||

||''noctem'' | ||''noctem'' | ||

||''' | ||'''nojśe''' | ||

||''notte'' | ||''notte'' | ||

||''noche'' | ||''noche'' | ||

| Line 674: | Line 673: | ||

||''piazza'' | ||''piazza'' | ||

||''plaza'' | ||''plaza'' | ||

||''plàça | ||''plàça'' | ||

||''place'' | ||''place'' | ||

||''praça'' | ||''praça'' | ||

| Line 684: | Line 683: | ||

||''ponte'' | ||''ponte'' | ||

||''puente'' | ||''puente'' | ||

||''pont | ||''pont'' | ||

||''pont'' | ||''pont'' | ||

||''ponte'' | ||''ponte'' | ||

| Line 729: | Line 728: | ||

|- | |- | ||

| Pater Noster qui es in caelis<br /><br />sanctificetur nomen tuum.<br /><br />Adveniat regnum tuum.<br /><br />Fiat voluntas tua, sicut in caelo et in terra<br /><br />Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie,<br /><br />Et dimitte nobis debita nostra sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris.<br /><br />Et ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo. Amen. | | Pater Noster qui es in caelis<br /><br />sanctificetur nomen tuum.<br /><br />Adveniat regnum tuum.<br /><br />Fiat voluntas tua, sicut in caelo et in terra<br /><br />Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie,<br /><br />Et dimitte nobis debita nostra sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris.<br /><br />Et ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo. Amen. | ||

| Padre-nor, qpid in kejo est.<br /><br />Nobe-ti saxartiśor iśśet.<br /><br />Majixeśu-ti beniperir | | Padre-nor, qpid in kejo est.<br /><br />Nobe-ti saxartiśor iśśet.<br /><br />Majixeśu-ti beniperir.<br /><br />Bojonta-ti in se terre pomot in kejo fiśor iśśet.<br /><br />Nor in diedoze der pana-nor pośișa.<br /><br />Et condonar depiśor-nor, pomot kondonamor depiśorer-nor <br /><br />Et no in tentașo duxar-ne, aut de majó liberer-ne. Amen. <br /> | ||

| Father our, who in heaven is.<br /><br />Name your venerated be.<br /><br />Kingdom your may it come.<br /><br />Will your in the earth like in heaven enforced be.<br /><br />To us in today give bread our daily<br /><br />And forgive trespasses our like we forgive trespassers our.<br /><br />And not in temptation lead us, but from evil deliver us. Amen.<br /> | | Father our, who in heaven is.<br /><br />Name your venerated be.<br /><br />Kingdom your may it come.<br /><br />Will your in the earth like in heaven enforced be.<br /><br />To us in today give bread our daily<br /><br />And forgive trespasses our like we forgive trespassers our.<br /><br />And not in temptation lead us, but from evil deliver us. Amen.<br /> | ||

| Our Father who art in heaven<br /><br />Hallowed be thy name.<br /><br />Thy kingdom come<br /><br />Thy will be done on earth like in heaven<br /><br />Give us today our daily bread<br /><br />And forgive us our trespasses like we forgive our trespassers<br /><br />And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen. | | Our Father who art in heaven<br /><br />Hallowed be thy name.<br /><br />Thy kingdom come<br /><br />Thy will be done on earth like in heaven<br /><br />Give us today our daily bread<br /><br />And forgive us our trespasses like we forgive our trespassers<br /><br />And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen. | ||

|} | |} | ||

Latest revision as of 16:00, 28 March 2024

Template:KylarisRecognitionArticle

| Suhalan | |

|---|---|

| Limba Suxaranu | |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [suxaɹanu] |

| Region | Suhala, North Coius |

| Ethnicity | Suhalan people |

Native speakers | ~10,200,000 (2020) |

Euclo-Satrian

| |

Early forms | |

Standard forms | Standard Suhalan

Standard Sojajianixe

|

| Dialects |

|

| Solarian script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Axatemie Nașonaje Suxaranu |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | shl |

Countries or regions where Suhalan is an official language Regions where Suhalan is spoken but is not recognized as an official language | |

Suhalan (Suxaranu [suxaɹanu] or Limba Suxare [limba suxaɹanu]) is a Solarian language spoken in southern Euclea and northern Coius. It is the official language of Suhala and is its primarily spoken language, as well as Suhalans in northern Tsabara. Many speakers of Suhalan are multilingual, typically with Vespasian, Rahelian, or Atudean. Diglossia is especially common in Suhala itself. Including the population of Suhalan-speakers outside of Suhala, Suhalan is spoken by approximately 10.2 Million people. The language has significant influence from Gaullican, Vespasian, and Rahelian, having many loanwords from these languages.

History

Suhalan is a Solarian language, descending from Solarian. Solarian was adopted relatively late into the Solarian period, and modern Suhalan possesses significant substrate influence from !Punic, with Suxaro-Suhalan having influence from Paleo-Suhalan. All varieties of Suhalan have adstratum influence from Gaullican, Rahelian, and Pardari with Tsabaro-Suhalan having more Gaullican influence in addition to influence. Suxaro-Suhalan holds significant Vespasian influence, especially on the western side of the island.

Solarian Period

Solarian was introduced to the Island around 113 BCE, when the island was first invaded by Solarian forces. Nimenese and Paleo-Suhalan were the most spoken languages prior to this, with Nimenese being prevalent on the south and eastern coasts. Some Piraean influence also existed on the west coast. The Island was slow to adopt Solarian, and its pre-existing languages stayed strong for centuries after its conquest, leading to the mockery of its inhabitants by Solarian writers who deemed them 'uncivilized'. Nevertheless, Solarian grew and by the 4th century BCE it was the majority language of the Island, with other languages relegated to secondary status in the centre and southern coast.

The Solarian of Suhala stayed much closer to Classical Solarian for much longer than other dialects, undergoing less sound changes and keeping more grammatical features, partially due to its distance from the rest of Euclea and periods of de facto self-governance. Eventually Old Suhalan had become distinct enough from Vulgar Solarian to be considered its own language by modern linguists, although there is little consensus on when this split happened, with timescales of between the 10th to the mid-12th century having been proposed. Old Suhalan was marked by a simplification of the case system into a nominative-accusative, a genitive, and a dative which took over the functions of the Solarian locative and ablative. Old Suhalan also possessed a freer word order and less loanwords than its contemporary Solarian languages, with the main superstrate influences from Rahelian, Pardari, and Gaullican being unevenly distributed across the island.

Old Suhalan was the primary language for internal administration, commerce, and literature, meaning that a large corpus is available. Solarian was largely used only for external communication with states in Euclea, and the Old Suhalan language held a markedly more prestigious position in Medieval Suhala than its contemporaries did in their respective areas. The earliest works in Suhalan are the Nepitagara Documents and the Sermons of St. Simjone, with Suhalan literature tracing its origins to the mid-12th century focusing on accounts of the lives of saints, rulers, or folk heroes, such as the Kanșode de Nepito.

After the Povelian invasion of the western side of the island, the use of Suhalan as an administrative gradually declined as more and more local documents were written in Povelian. The Suhalan on the west side of the island also underwent significant influence from Povelian, adopting many of its spelling conventions and loaning many words. Suhalan on the east side, by contrast, took in far fewer loanwords. Futher dialectical differences would emerge, with Coian Suhalan, Central Suhalan, West Suhalan, and East Suhalan becoming more distinct in their phonologies and lexicons. The earliest examination of Suhalan from a linguistic perspective would be done by !Dante, defining it as an eia language, and noting that it "Displays 3 vulgar languages", and remarking that Suhala's geographic qualities were the likely cause. Later Suhalan-focused analysis would mostly come in the 16 and 1700s, from both Povelian and Suhalan intellectuals.

Modern Suhalan

Early on under Etrurian control, the Suhalan language was mostly left untouched, however it stopped being used for administrative purposes and most literature written on the island began to be written primarily in Vespasian. The language quickly became associated with rural people and the poor, with educated Suhalans sometimes forgoing its use entirely even in private. It was not legally recognized as a language after Etrurian federalization, however the rights of Suhalan speakers were somewhat protected and the language continued to be widely used among most people on the island.

In 1885, the first comprehensive grammar of Suhalan was published by Suhalan writer Gafrieje Ardasu Sartore de Seśari, named Unu Anajusu Compjeśu des Limba Suxaranu, or "A Comprehensive Analysis of the Suhalan Language". Gafrieje would write other major works of Suhalan literature, including Su Korvu Rubru Sanqbine d'Ajambasaj ("The Blood-Red Raven") and Laglva Emesu("Emesis Blue"). His work, as well as the work of a few other Suhalan writers, managed to gain recognition for the Suhalan language, which was acknowledged as a regional language of Etruria in 1901.

Suhalan achieved a brief moment of popularity after the Great War, with the work of Suhalan-language poets, writers, and intellectuals being widely consumed. This came to a crashing halt with the rise of the National-Solarians, who suspected Suhalans of harboring councilist and secessionist sympathies, and who supported the Etrurianization of Suhala. Etrurianization involved the favoring of Etrurian groups in Suhala, whose numbers swelled, and had a devastating effect on the public use of the Suhalan language. Use of Suhalan in public was criminalized, and children who spoke in it during school would be beaten. These efforts lead to the Suhalan liberation movements adopting the defense of the Suhalan language as one of their main goals, with the Fronte Naşonaje bro su Padria et Konkorśa publishing their seminal pamphlet "Saje Ajexe - Finoas Rebiteto!" ("Peace be Unto You - Until the Reseeing"), railing against the supression of Suhala. Many works of Suhalan literature were smuggled out of the island into temporary safe havens in nearby countries. Many Suhalans left the country between the Great War and the Solarian War, and strengthened Suhalan communities in Eastern Euclea and the Asterias, with a significant Suhalan-language community developing in Eldmark.

After Suhalan independence, the language quickly became more used in everyday life, aided by the pro-Suhalan position of the new ruling parties and by the slow emigration out of the country by Etrurians. Suhalan became the national language of commerce and governance, and soon it replaced Vespasian in literature. Under the Ligbe Rufra de Suxare, a concerted policy of "De-Etrurianization" was implemented, with the creation of the Axatemie Nașonaje Suxarano to regulate the Suhalan language and many Vespasian loanwords for technical field being replaced by ones loaned from Solarian, Gaullican, or calqued from Vespasian. Western Suhalan was also suppressed, being seen as having too much Vespasian influence, and the language underwent significant orthographic reform, removing instances of digraphs like ll and sc and standardizing the use of letters like Çç and Şş. This policy of De-Etrurianization was halted after the LRS regime was replaced, and nowadays Suhalan dialects recieve more support from the government.

Nearly all Suhalan speakers are literate, with Suhalan communication online being prevalent, and most linguists and Suhalan language authorities agree that the language's future is positive. Overall, Suhalan is the most spoken language in Suhala, even despite the recent influx of primarily Atudean and Rahelian speaking immigrants, due to the efficacy of Suhalan language-learning programs.

Phonology

Suhalan has 20 consonant and 5 vowel phonemes, with a phonological inventory relatively similar to that of other Solarian languages. Its most crosslinguistically rare phonemes are the dental affricate /θ/ and the labiovelar plosives.

Consonants

| Bilabial | Dental | Alveolar | Post-Alveolar/Palatal | Velar | Labiovelar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | n | |||||

| Plosive | voiceless | p | t̪ | k | k͡p | ||

| voiced | b | d̪ | g | ɡ͡b | |||

| Fricative | f | θ | s | ʃ | x | ||

| Affricate | voiceless | t͡ʃ | |||||

| voiced | d͡ʒ | ||||||

| Approximants | l / ɹ | j / j̃ | w | ||||

Notes:

- Geminate fricatives and fricatives before the liquids /l, r/ are allophonically voiced

- /n/ and /m/ allophonically assimilate into [ɱ, ŋ, ŋ͡m] before consonants with their places of articulation, i.e /nf/ and /ng/ are realized as [ɱf] and [ŋg]

- /n/ and /m/ allophonically assimilate into [ŋ] after /u/ and /ɔ/

- /ʃ/, /t͡ʃ /, and /d͡ʒ/ are typically realized as [ʃʲ] and [t͡ʃʲ] [d͡ʒʲ]

- Central Suhalan dialects replace the phonemes /k͡p/ and /ɡ͡b/ with /ʍ/ and /w/ respectively

- Many younger speakers of Central Suhalan dialects, due to hypercorrection, often replace instances of [w] with [ɡ͡b] in situations where [w] would be correct in Standard Suhalan, i.e Standard Suhalan Vicljom becomes Qbicljom

- Many speakers of Central Suhalan dialects hypercorrect /l/ into /j/ in situations where the former would be correct in Standard Suhalan, i.e Standard Suhalan Limba (Languge) and Falsu (Deceptive, Sneaky) becoming Jimba and Fajsu

- In the Northwest Suhalan dialect, /d͡ʒ/ is realized as [ʎ], likely due to influence from Vespasian.

Vowels

| Front | Central | Back | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | u | ||

| Open-mid | ɛ | ɔ | ||

| Open | a | |||

Notes:

Orthography

Suhalan uses the Solarian alphabet, with 5 vowel letters (along with an acute diacritic to distinguish homophones, and 24 consonant letters.

| Suhalan Letter | Suhalan Name | IPA sound | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| Aa | A | a | |

| Bb | Be | b | |

| Cc | Ce | k | |

| Çç | Çe | tʃ | Represents dʒ in Coio-Suhalan |

| Dç dç | Adçe | dʒ | Represents dð in Coio-Suhalan |

| Dd | De | d̪ | |

| Ee | Ej | ɛ | |

| Ff | Ef | f | |

| Gg | Ge | g | |

| Ii | I | i, j* | Represents the semivowel j when before a vowel |

| Jj | Je | j | |

| Kk | Kab | k | |

| Ll | El | l | |

| Gl, gl | Egle | dʒ ,ʃ | Represents dʒ word-initially and ʃ intervocalically. Represents ʎ in Northwest Suhalan and word-initially in Central Suhalan, ð in Coio-Suhalan, and ʒ intervocalically in Central Suhalan |

| Mm | Eme | m | |

| Nn | Ene | n | |

| Oo | O | ɔ | |

| Pp | Pi | p | |

| Qp, qp | Aqpa | k͡p | |

| Qb, qb | Aqba | ɡ͡b | |

| Rr | Are | ɹ | |

| Ss | Es | s | |

| Şş | Eşu | ʃ | Represents ʒ in Coio-Suhalan |

| Śś | Śeśa | θ | |

| Tt | Ta | t | |

| Uu | U | u, w | Represents the semivowel w when before a vowel |

| Vv | Ve | w | |

| X | Exir | x | |

| Z | Eze | ʃ | Represents ʒ in Central Suhalan and ð in Coio-Suhalan |

Grammar

Suhalan is grammatically and typologically similar to other Solarian languages, and is a fusional language. Nouns and adjectives are inflected for case, gender, and number. Verbs are conjugated for tense, aspect, mood, as well agreement with the person and number of their subject.

Pronouns

Suhalan has 6 personal pronouns that decline for 3 cases, those being the nominative, accusative, and dative. Pronouns can be cliticised, with dative pronouns being procliticised before verbs with initial vowels (written with an apostrophe '), and encliticised (written with a hyphen "-" between the verb and pronoun) after nouns to indicate possession. Accusative pronouns can be encliticised (written with a hyphen "-" between the verb and pronoun). It also possesses a three-way distinction between demonstratives, proximal, medial, and distal.

Personal Pronouns

| case | Number and person | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |||||||

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd M. | 3rd F. | 1st | 2nd | 3rd M. | 3rd F. | |

| Nominative | Jo | Tu | Ide | Ida | Nor | Bor | Idi | Ider |

| Accusative | Me | Te | Idu | Ida | Ne | Be | Idor | Idar |

| Dative | Mi | Ti | Si | Si | Nośre | Besdre | Sir | Sir |

Demonstrative Pronouns

| Case | Type and Number | |||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | |||||

| Proximal | Medial | Distal | Proximal | Medial | Distal | |

| Nominative | Unc/Anc | Iśśu/a | Icle/a | Or / Ar | Iśśor/ar | Iclor/ar |

| Oblique | Uic | Iśśi | Icli | Ir | Iśśir | Iclir |

Nouns

All nouns in Suhalan are either masculine or feminine, and the gender of a noun can usually be told from its ending. However, there are nouns which have a feminine ending and follow a feminine declension pattern but are masculine, and vice verse, leading to some ambiguous situations. Suhalan posesses two grammatical numbers, the singular and plural. It also has two grammatical cases, the Nominative and the Oblique. The nominative is used for the subjects and direct objects of verbs, while the oblique is used for nouns with prepositions or the indirect objects of verbs. Nouns can be grouped into declension patterns.

Femidina

Nouns in the Feminine declension tend to come from the Latin 1st declension.

| Case | Singular | Plural |

| NOM | kas-a | kas-ar |

| OBL | kas-e | kas-ir |

Efixenu

Nouns in the Epicene declension tend to come from the Latin 3rd declension, and can be either masculine or feminine.

| Case | Singular | Plural |

| NOM | arbor-e | arbor-er |

| OBL | arbor-i | arbor-ipor |

Masculinu I

Nouns in the Masculine I declension typically come from the Latin second declension

| Case | Singular | Plural |

| NOM | kan-u | kan-or |

| OBL | kan-o | kan-ir |

Masculinu II

Nouns in the Masculine II declension typically come from the Latin fourth declension. Many nouns that use the Masculine II declension are feminine, and use feminine articles and feminine adjectival agreement.

| Case | Singular | Plural |

| NOM | man-u | man-or |

| OBL | man-ui | man-ipor |

Verbs

Verbs are highly inflected, and belong to one of three conjugation patterns classified by their infinitive endings, are, ere, and ire. Suhalan is traditionally regarded to have 4 tenses, the present (bresente), preterite (preśeriśu), imperfect past (imperfejśu), and future (fuśuru), as well as 3 moods, the indicative (indixaśibu) , subjunctive (supjunctibu), and imperative (imperaśibu).

-are verbs

| Kantare, "to Sing" | |||||||||

| Mood | Tense & Aspect | Number and person | Estmerish equivalent (only sg. 1st) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||||||||

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | ||||

| Indicative | Present | Kant-o | Kant-ar | Kant-at | Kant-amor | Kant-aśir | Kant-ant | I sing | |

| Preterite | Kant-abi | Kant-abiśśi | Kant-abit | Kant-abimor | Kant-abiśśir | Kant-aberunt | I sang (at a specific point of time) | ||

| Imperfect | Kant-apa | Kant-apar | Kant-apat | Kant-apamor | Kant-apaśir | Kant-apant | I was singing | ||

| Future | Kant-arav | Kant-arar | Kant-aret | Kant-aremor | Kant-arajśir | Kant-arent | I will sing | ||

| Subjunctive | Present | Kant-e | Kant-er | Kant-et | Kant-emor | Kant-eśir | Kant-ent | If I sing, May I sing | |

| Preterite | Kant-aberi | Kant-aberir | Kant-aberit | Kant-aberimor | Kant-aberiśir | Kant-aberint | If I sang (at a specific point of time) | ||

| Imperfect | Kant-are | Kant-arer | Kant-aret | Kant-aremor | Kant-areśir | Kant-arent | If I was singing | ||

| Future | Kant-araj | Kant-arïar | Kant-arajat | Kant-arajamor | Kant-arajaśir | Kant-ajant | If I will sing | ||

| Imperative | Present | Kant-a | Kant-emor | Kant-aśe | (You) sing! | ||||

-ere verbs

| Sapere, "to know" | |||||||||

| Mood | Tense & Aspect | Number and person | Estmerish equivalent (only sg. 1st) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||||||||

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | ||||

| Indicative | Present | Sap-jo* | Sap-er | Sap-et | Sap-emor | Sap-eśir | Sap-ent | I know | |

| Preterite* | Sap-vi | Sap-viśśi | Sap-vit | Sap-vimor | Sap-viśśir | Sap-verunt | I knew (at a specific point of time) | ||

| Imperfect | Sap-epa | Sap-epar | Sap-epat | Sap-epamor | Sap-epaśir | Sap-epant | I was knowing | ||

| Future | Sap-epo | Sap-epir | Sap-epit | Sap-epimor | Sap-epiśir | Sap-epunt | I will know | ||

| Subjunctive | Present* | Sap-ja | Sap-jar | Sap-jat | Sap-jamor | Sap-jaśir | Sap-jant | If I know, May I know | |

| Preterite* | Sap-veri | Sap-verir | Sap-verit | Sap-verimor | Sap-veriśir | Sap-verint | If I knew (at a specific point of time) | ||

| Imperfect | Sap-ere | Sap-erer | Sap-eret | Sap-eremor | Sap-ereśir | Sap-erent | If I was knowing | ||

| Future | Sap-eperi | Sap-eperir | Sap-eperit | Sap-eperimor | Sap-eperiśir | Sap-aperint | If I will know | ||

| Imperative | Present | Sap-e | Sap-imor | Sap-eśe | (You) know! | ||||

Notes: Verbs with roots that end in t, d, k, or g will undergo palatalization when conjugated for the 1st person present indicative and the subjunctive preterite, becoming ș, ç, or dç respectively. Verbs with roots that end in k or g or a vowel will become qp qb or change the v into a b respectively when conjugated for the indicative and subjunctive preterite.

-ire verbs

| Benire, "to arrive" | |||||||||

| Mood | Tense & Aspect | Number and person | Estmerish equivalent (only sg. 1st) | ||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Singular | Plural | ||||||||

| 1st | 2nd | 3rd | 1st | 2nd | 3rd | ||||

| Indicative | Present | Ben-jo* | Ben-ir | Ben-it | Ben-imor | Ben-iśir | Ben-junt* | I arrive | |

| Preterite | Ben-ibi | Ben-ibiśśi | Ben-ibit | Ben-ibimor | Ben-ibiśśir | Ben-iberunt | I arrived (at a specific point of time) | ||

| Imperfect* | Ben-jepa | Ben-jepar | Ben-jepat | Ben-jepamor | Ben-jepaśir | Ben-jepant | I was arriving | ||

| Future* | Ben-ja | Ben-jer | Ben-jet | Ben-jemor | Ben-jeśir | Ben-jent | I will arrive | ||

| Subjunctive | Present * | Ben-ja | Ben-jar | Ben-jat | Ben-jamor | Ben-jaśir | Ben-jant | If I arrive, May I arrive | |

| Preterite | Ben-iberi | Ben-iberir | Ben-iberit | Ben-iberimor | Ben-iberiśir | Ben-iberint | If I arrived (at a specific point of time) | ||

| Imperfect | Ben-ire | Ben-irer | Ben-iret | Ben-iremor | Ben-ireśir | Ben-irent | If I was arriving | ||

| Future | Ben-iperi | Ben-iperir | Ben-iperit | Ben-iperimor | Ben-iperiśir | Ben-iperint | if I will arrive | ||

| Imperative | Present | Ben-i | Ben-imor | Ben-iśe | (You) arrive! | ||||

Notes: Verbs with roots that end in t, d, k, or g will undergo palatalization when conjugated for the 1st person present indicative and the subjunctive preterite, becoming ș, ç, or dç respectively.

Syntax

Suhalan is a head-initial language, being typically SVO, placing adjectives after nouns, using prepositions. Its most prominent head-final syntax is the placing of indirect objects before the verb. Suhalan interrogative phrases are SOV, so while the phrase "My friend writes books" would be said (SVO) as:

- Amixu-mi ixxipet kiśapir

while the phrase "My friend writes books?" is said (with rising intonation & SOV) as:

- Amixu-mi kiśapir ixxipet?

Suhalan is also a pro-drop language, meaning that there are sentences with objects and verbs and no stated subject, like

- Bro s'ixxipjo kiśapir-mi

meaning "I write my books for him" (also note that the oblique pronoun si becomes a proclitic before the verb with an initial vowel and that the oblique pronoun mi, used as a genitive, becomes an enclitic after kiśapir, or "books" in the oblique case.

Sample Text and Vocabulary Comparison

Vocabulary Comparison with other Solarian Languages

| Estmerish | Solarian | Suhalan | Etrurian | Esmeiran | Montecaran | Gaullican | Luzelese | Tosuton |

| key | clāvem | glabe | chiave | llave | ciàve | clé | chave | clau |

| night | noctem | nojśe | notte | noche | nòte | nuit | noite | nit |

| sing | cantāre | kantare/-je | cantare | cantar | cantàr | chanter | cantar | cantar |

| goat | capram | kabra | capra | cabra | càvra | chèvre | cabra | cabra |

| language | linguam | limba | lingua | lengua | lèngua | langue | língua | llengua |

| plaza | plateam | piașa | piazza | plaza | plàça | place | praça | plaça |

| bridge | pontem | ponte | ponte | puente | pont | pont | ponte | pont |

| church | ecclēsiam | eglesia | chiesa | iglesia | céxa | église | igreja | església |

| hospital | hospitālem | offiśaje | ospedale | hospital | ospedàl | hôpital | hospital | hospital |

| cheese | cāseum (fōrmāticum) | casiu, formaśixu, formadço, | cacio, formaggio | queso | formàxo | fromage | queijo | formatge |

Sample of The Lord's Prayer

| Solarian | Suhalan | Direct Translation | Estmerish |

|---|---|---|---|

| Pater Noster qui es in caelis sanctificetur nomen tuum. Adveniat regnum tuum. Fiat voluntas tua, sicut in caelo et in terra Panem nostrum quotidianum da nobis hodie, Et dimitte nobis debita nostra sicut et nos dimittimus debitoribus nostris. Et ne nos inducas in tentationem, sed libera nos a malo. Amen. |

Padre-nor, qpid in kejo est. Nobe-ti saxartiśor iśśet. Majixeśu-ti beniperir. Bojonta-ti in se terre pomot in kejo fiśor iśśet. Nor in diedoze der pana-nor pośișa. Et condonar depiśor-nor, pomot kondonamor depiśorer-nor Et no in tentașo duxar-ne, aut de majó liberer-ne. Amen. |

Father our, who in heaven is. Name your venerated be. Kingdom your may it come. Will your in the earth like in heaven enforced be. To us in today give bread our daily And forgive trespasses our like we forgive trespassers our. And not in temptation lead us, but from evil deliver us. Amen. |

Our Father who art in heaven Hallowed be thy name. Thy kingdom come Thy will be done on earth like in heaven Give us today our daily bread And forgive us our trespasses like we forgive our trespassers And lead us not into temptation, but deliver us from evil. Amen. |