Almiaro

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Almiaro | |

|---|---|

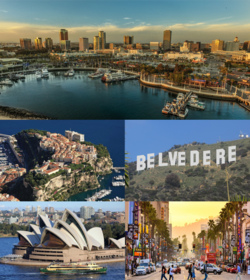

Clockwise from top: New Almiaro skyline and Marina, Belvedere sign, Downtown Belvedere, Jardin d'Almiaro exhibition centre, the fortified portion of Old Almiaro with the Doge's palace | |

| Government | |

| • Elected Body | Almiaro City Council |

| • Mayor | Antonia Candela (LL) |

| Area | |

| • Urban | 452 km2 (175 sq mi) |

| • Metro | 3,732 km2 (1,441 sq mi) |

| Population | |

| • City and Municipality | 876,813 |

| • Density | 1,939/km2 (5,020/sq mi) |

| • Urban | 2,013,212 |

| • Metro | 3,854,931 |

| Demonym | Almiaran |

| Time zone | UTC 0 |

Almiaro is a major city in Midrasia, and the largest city within the region of Riviera. The city is located in the far-south of the nation, across an inland bay of the same name. The city's population is 876,813, with 3,854,931 people in the city's metropolitan area, making it the fifth largest city in terms of city population, and fourth largest if metropolitan area is included, behind Lotrič, Berghelling and Bordeiu.

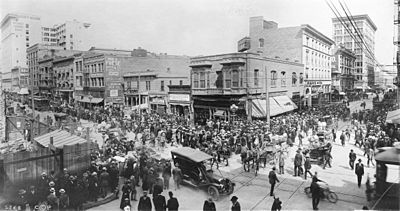

Almiaro was believed to have been founded by Chalcian colonists at some point during the Sixth Century BCE. The city operated as an independent city-state for some time, before being absorbed peaceably into the Fiorentine Empire. Under the Fiorentines, Almiaro expanded to become one of the major trading ports of the empire and a key military outpost for operation in the Asur. Following the fall of the Fiorentines, Almiaro continued to prosper, this time as an independent city-state republic under the Doge, an elected member of the city's powerful mercantile families. Whilst Almiaro continued to prosper under this arrangement, the rise of the nearby Aquidish Kindom threatened the city's prosperity. With the construction of an Aquidish trading port at Pale diverting trade away from the city, Almiaro turned to Midrasia for protection, with the small city-state soon devolving into little more than a vassal state of Midrasia. During the Midrasian revolution of 1784-1791, the Doge of the city was overthrown, leading Almiaro to become an integrated part of the country and Midrasia's main southern port. The city underwent considerable expansion during the Nineteenth and Twentieth Centuries due to immigration, with the city now playing host to Midrasia's media and cultural sector. The city itself is renowned for its diversity, arts and tourism scene, whilst the old town of Almiaro is also known as a hub of the ultra-rich, espousing a large number of mansions and historic sites.

History

Ancient history

It is unknown exactly when the city of Almiaro was founded, though most sources indicate it was founded at some point in the mid-Sixth Century BCE. Most estimates have put a founding date at 556 BCE, though this estimate has come under fire in recent years. All that is known is that the city was founded by Chalcian colonists after the founding of Argolis (modern-day Argois), but before the beginning of the Fifth Century BCE. Little evidence exists of groups occupying southern Riviera before the arrival of the Chalcians, though it is possible that nearby tribes such as the Benedii and Kalimans may have held settlements within the region.

By the mid-Fourth Century BCE, Almiaro was a fledgeling trade port, with known connections throughout the northern Asur. It is believed that Almiaro mostly traded in textiles and linens, with many of these travelling from as far east as modern-day Transcandar. It is unknown exactly how ancient Almiaran society was organised, though most sources suggest it was a form of elective monarchy in which elites would vote on a new leader who would rule until death. By 356 BCE, Almiaro had come under the domain of the Empire of Artakhshathra. Faced with a significant invasion force on their doorstep, Almiaro refused to surrender to Artakhshathra, leading his forces to begin a siege of the city. Cut off from overseas trade, hunger soon spread across the city. 100 days into the siege, a strike force managed to sneak into the city by night, torching Almiaro's Library in the process. It was during this attack that it was believed that most sources on pre-Fiorentine Almiaro were lost. Following the incident, the city surrendered, becoming nominally independent under Artakhshathra's rule. With Artakhshathra's death several years later, the city quickly transformed back into its independent state, with a lack of outside authority preventing Artakhshathra's Iranic generals from maintaining power.

With its newfound independence, Almiaro began to regain its position as a major trading port. By this point, historians note that the city was definitively ruled as a monarchy, though this time a hereditary one. Ruled by the Lucidite dynasty, Almiaro began to open trade ties further across the Asur, reaching north Majula and Arabekh, and establishing key trading ties with the newly formed Fiorentine League. With the expansion of Fiorentina south, the city-state came under the Empire's influence, contributing manpower and resources to the Fiorentine campaigns in southern Aquidneck. By 202 BCE, the last member of the Lucidite dynasty died without a legitimate heir. Within his will, the city was left to the Fiorentine Republic, which appointed a governor to oversee its newly acquired territory. Almiaro, (or Almiarum was had became known) enjoyed a considerable number of rights and privileges under the Fiorentines, being one of the main naval bases and trading ports of the empire, its citizens receiving Fiorentine citizenship, and being designated a free city in 98 BCE.

As the empire declined however, the city's privileges were quickly eroded. Faced with Germanic invasions from the north, and the sack of Laterna in 482, Almiaro became a refuge for those fleeing the Langobardic invasion into Riviera. The city's steep cliffs and walls prevented any direct assault by invaders, allowing the city to withstand the Langobards. During this period it is believed that the first Doge of Almiaro was elected, in Tettius Strabo. The founding myth of the Almiaran Republic suggests that Strabo was appointed leader for his heroics during a siege of the city by the Langobards, wherein his actions were integral to defeating the attackers. With Almiaro becoming effectively independent, the Imperial remnant sent a force attempting to retake the city, though this was easily defeated due to a combination of strategy by the Almiarans and poor sailing weather.

Republic of Almiaro

For just over a millennium, between 482 and 1485, Almiaro functioned as a de facto independent city-state republic. The city was ruled by the Doge, elected by the Council of the Wise from among the elite patrician families of the republic. Throughout this period, Almiaro can be seen to have operated as both a hereditary republic and an oligarchy, with politically powerful families usually establishing a continuous ruling dynasty, whilst in certain periods, power generally flowed to whoever was able to leverage the most patronage over the mercantile classes. Almiaro benefitted considerably from Asuran expansion during the medieval age, with the Millenial Crusades allowing the republic to establish greater trade ties and small trading colonies in northern Arabekh. Additionally, the discovery of the New World, and of trading routes to Savai led an increasing number of goods to be ferried towards the republic, greatly increasing the wealth and population of the city-state.

However, this booming trade was noticed by the rising Aquidish Kingdom, which attempted to tap into Almiaro's trading networks by expanding the fishing town of Pale into a fully functioning trade port. The new town soon became the largest in Aquidneck, surpassing Almiaro and drawing an increasing percentage of goods away from the republic. In response, the Doge of Almiaro signed an agreement with the King of Midrasia, at the time, Philip II; which granted Midrasia protection rights over the republic and its trade routes, preventing Aquidish piracy and directing Midrasian-bound goods to Almiaro. These agreements ultimately culminated in the Almiaro war of 1432-1434, resulting in a status-quo ante bellum. After several more years of struggles, the economy of Almiaro began to decline, losing its colonies in Arabekh, and its trade goods to Pale. With the Midrasian kingdom being unable to live up to its promises of reducing Aquidish trade influence, the Doge of Almiaro, Gabbriello de Calvenzano renegged on the previous treaty, refusing to pay the funds owed to the Midrasian king because of the war and ending Midrasian trade privileges in the city. In response, the Midrasian King, Louis VI sent an invasion force to depose the Doge and install a Midrasian-friendly ruler. The invasion of 1485 saw de Calvenzano, and replaced by Bartolo Barbadori. Whilst Almiaro continued to operate autonomously from this point on, a portion of its tax income was paid into the Midrasian coffers and Midrasian traders gained permanent privilieges in the city, effectively devolving the republic into a vassal state.

Midrasian Almiaro

For several centuries following the deposition of Gabbriello de Calvenzano, Almiaro remained a de jure independent state, though as time went on Midrasian influence grew, with Midrasian law holding precedence over the state. This gradual dissolution of autonomy whilst greatly resented by a significant portion of the population, held in the favour of many mercantile classes who greatly benefitted from Midrasian influence within the republic. Under the Midrasian yoke, investment poured into the city, whilst Midrasian shipping throughout the west of the kingdom was diverted to the port of Almiaro. In addition, the noble classes of the city retained their rights and privileges, and no action could be taken by the Midrasian crown within the republic without the express approval of the Doge.

The status of the city came under question during the Midrasian Civil War however, with the abolition of the monarchy leading the earlier Mydro-Almiaran treaty to become defunct. Whilst many within Almiaro were sympathetic with the burgeoning republican movement sweeping across the nation, many within the Almiaran patrician classes continued to support the monarchy, whilst others supported outright independence. This limbo was sustained for several years after the execution of 1624. The Act for the Termination of Regency, passed by the Lotrič Parlement in 1642 led Almiaro to become an independent Republic by proxy, though only several years later in 1652, an armada was sent by Consul Jauffre Devreux to besiege the city, forcing the Doge to recognise Midrasian overlordship, signing an extension to the prior Mydro-Almiaran treaty.

Although Midrasian suzerainty over the city was confirmed following the civil war, the city remained a considerable point of tension between Midrasia and Aquidneck throughout their numerous naval wars fought throughout the Seventeenth and early Eighteenth Centuries. The Third Mydro-Aquidish War of 1712 was particularly notable for the Aquidish blockade which surrounded the city and ultimately led to its surrender. Whilst the city would be given back to Midrasia during peace negotiations, it would not be until the signing of the International Waterway Pact of 1747 that the naval conflicts involving Almiaro would subside. The agreements proved a great benefit to Almiaro, effectively eliminating piracy from other Asuran states and ensuring that Almiaro could peacefully trade without the threat of another naval war. As such, considerable wealth flowed back into the city which began to recover from its slump of the Sixteenth Century. Historians suggest that this in many ways contributed to the easing of tensions between Midrasia and Almiaro, with many Almiarans viewing their Midrasian overlords as having a positive benefit on the city and surrounding region.

Whilst many Almiarans may have warmed to their Midrasian overlords, as the population of Almiaro grew, considerable divisions had begun to emerge between the mercantile patrician families and the lower classes of the city. As ideas of liberalism began to take hold across Midrasia, and more and more people had access to basic literacy skills, movements aimed at curbing the power of the Doge began to take shape, posting criticisms of the office and the Council of the Wise. Additionally, calls for the city to return to its ancient democratic origins also gained traction. A protest organised in 1782 calling for the establishment of a local assembly where residents could heir grievances against the Doge was quashed by military force, leading the sitting Doge, Bardo di Monastra to become one of the most reviled figures in Almiaran history. With the outbreak of the wider Midrasian revolution in 1784, local Almiaran residents took it upon themselves to assassinate di Monastra and create a new democratic assembly. This action caused great outrage among the patrician classes who mobilised a mercenary army to put the peasantry back in its place. In 1786, Midrasian forces loyal to the new democratic assembly entered the city, cheered on by the local population. The Midrasian army quickly defeated the patrician force and declared Almiaro to be an integral part of the new republic, "enjoying all rights that common men of the new republic are endowed with". Throughout the remainder of the revolution, republican forces held the city, in spite of Consular attempts to retake it. Nevertheless, considerable atrocities were committed against the traditional patrician classes, with many being subject to kangaroo courts and executed. Following the conclusion of the revolution, Almiaro remained a part of Midrasia, albeit without its autonomy. Midrasian citizenship was extended to all residents, and males aged over 21 were allowed to vote in elections. Despite attempts by other monarchies across Asura to pressure Midrasia into restoring the Doge and Almiaran autonomy, no such action was taken by the new democratic Midrasian republic.

Expansion

With Almiaro under official Midrasian control following the revolution, the new government was able to exert a much greater level of influence on the region than those which had come before. Midrasian law was enforced throughout the region, and though attempts to switch from the Rivieran language to Midrasian were attempted, these were repealed after considerable opposition. Whilst Almiaro had been Midrasia's largest southern port, its infrastructure paled in comparison with other cities such as Argois and Bordeiu. In addition to a rising population due to the effects of rural migration, the government took the decision to greenlight an expansion of the city. Rather than expanding on the old town located at the mouth of the Almiaro Bay, the decision was taken to convert a small farming village called Casomo on the other side of the bay into a new district of the city, named New Almiaro. The flatter land located in this area suited construction much more than the old town, it also made the construction of new docklands for increased shipping capacity far easier. Beginning in 1849, the old farmlands were destroyed and replaced with a new modern city centre.

Though this new town grew considerably throughout the Nineteenth Century, it continued to lag behind the much larger cities of Midrasia, with a population of only around 150,000 by 1890. Though a key port city, most trade traffic continued to be diverted toward Argois and Bordeiu until the Twentieth Century. Additionally, the city lacked a considerable industrial sector, and with no other major city for many miles, most traffic coming into Almiaro harbour constituted agricultural products and a small number of consumer goods. Following the Great War however, this changed. With the country reeling from the effects of the conflict, a national program to rebuild the country began. Part of this program involved constructing a new port in a much more secure location than Argois so that maritime trade could be protected during wartime. Almiaro was chosen to be this port, with a considerable effort to build a new naval base and trade port getting underway. Furthermore, the demand for housing for returning soldiers and migrants coming to the country through the Colonial Migration Act. As a result, Almiaro underwent a housing boom from 1915-1927 and again in the 1940s following the Second Great War. This saw the city transformed beyond recognition. Much of the northern section of the Bay of Almiaro was transformed into a modern city, utilising a grid-based layout with art deco and art nouveau architecture covering much of the city, giving it a distinct identity to other Midrasian cities.

The city's expansion continued throughout the Twentieth Century, with the city soon containing the largest foreign-born population in all of Midrasia, with an especially large black Midrasian community. The diversity of the city contributed greatly to the growth of the city's art, culture and media scene which now makes up the largest sector of the city's economy. In 1912 the small suburb of Belvedere soon became the home of a thriving film industry as the popularity of movies boomed across the country and Asura. A large number of film studios were set up within Belvedere, from which were birthed many of today's major Asuran film companies such as Zenith, Mondiale and Lino Gauci. Nevertheless, Belvedere remained in a pitched battle against other Aeian film hubs, leading the government to institute measures to attract companies to the city and promote its image worldwide. These involved tax incentives and the construction of the now world-famous Belvedere sign. In addition, with the invention of the radio and television, the city also became the host of Midrasia's media sector, with a number of media conglomerates basing their operations out of the city.

Today the city of Almiaro continues to grow at a considerable rate and is one of the most wealthy areas of Midrasia. The city has a growing migrant population, mostly drawn from overseas, but also from other areas of Midrasia itself. Much of this migration is directed at New Almiaro, whilst Old Almiaro's population remains relatively static, mostly due to the very high cost of properties within the area. The standard of living within the city remains incredibly high relative to other areas of the country, however, the city has an incredibly high cost of living.

Demographics

Economy

Culture

Transportation

Road transportation

Public transport in Almiaro along roads is made up of coach, bus and taxi services which operate in and around the region. Coach services offer inter-city travel throughout Midrasia's southern regions and even as far north as the capital via a direct route. Such coach operators generally provide a cheaper, albeit much slower alternative to rail transportation throughout Midrasia's regions. Bus transport in the city is operated publically by the local council and provides regular routes throughout the city's various districts and the surrounding regions. Services usually run between the suburbs and downtown, though the number 7 service runs a regular circuit between Belvedere and Benedormo. Taxi services in the city operate bilaterally, with official taxi operators having to be licensed with the Almiaro city council. Official Almiaro taxi cabs are painted black and yellow and are usually an Âge Estrat or similar sedan vehicle. Unofficial taxis operated by the mobile-app company RYDE also operate within the city and do not have to be licensed with the city council as they are not officially classified as taxis. Though they may provide a cheaper more convenient alternative to official taxi cabs, local authorities have begun to clamp down on RYDE for their use of legal loopholes to bypass licensing fees.

Almiaro has a number of highway links, making it a fairly well-connected city. Whilst the city itself has no official ring-road, a number of highways do circle the city, these being the A19, 32, 57, 59 and 62. The A19 was the first highway constructed in Almiaro and links the city to the north, running through almost the entirety of the province of Riviera. The A32 passes through the nearby Benedian hills, connecting the city to the Aquidish border. The A57 does likewise though from the other side of the city and also passes Almiaro airport. The A59 meanders through the Colombian Hills near the Old Town, connecting to a number of small coastal towns and the Colombia national park. The A62 meanwhile connects Almiaro to the nearby resort town of Benedormo.

Rail transport

Almiaro has a number of rail transport systems, which are broken into the national rail systems, which are run as part as the Lombard rail franchise; rapid transit, via the Almiaro Metro; and the city's light rail or tram system.

The city's national rail system connects to both the Relier High-Speed Network and the national railway system as part of the Lombard Rail Franchise. Two stops on the Relier network are located in Almiaro, being at the city's airport and Almiaro-Republic station. Relier trains from Almiaro regularly run between Almiaro, Lotrič or Bordeiu in terms Midrasian destinations; whilst routes also run to the Aquidish cities of Pale and Torden. National rail services via Lombard railways also operate across the local area, departing from Republic Station. These routes connect to a number of stations in the region of Riviera before terminating at destinations such as Mydroll, Ferrero and Monza.

Almiaro also plays host to a metro system which though expansive, is one of the smaller such systems in Midrasia. The Almiaro metro features four lines, labelled Red, Blue, Yellow and Green. The Red line is a circular system running through the New Almiaro downtown. The Blue line runs from Republic station northward towards Almiaro Airport. The Yellow line runs from downtown Almiaro into Belvedere. Finally, the Green line runs from Republic Station across the Liberty Bridge to Old Almiaro.

The city also features a modern expansive tram system, which operates in both Belvedere and the suburbs of New Almiaro as two separate networks. The system mostly utilises roadways with trams running alongside cars. Though the system was originally utilised across the entirety of New Almiaro during the mid-twentieth century, the system was scrapped in 1975 oweing to its outdatedness and lack of usage. In 2002 however, the system was revived in select portions of the city with new modernised lines and tram cars. The system has seen a significant growth over the past decades, with the council planning to expand the system throughout more of Almiaro's outer regions.

Airports

Almiaro has two public airports within the vicinity of the city itself. By far the largest of these three is Almiaro-Salvatore Luciana Airport which is the largest airport in southern Midrasia. Almiaro airport has two runways with annual passenger numbers in excess of 30 million, making it the 4th largest airport in the country. The airport is served by train through the Relier as well as through the Almiaro Metro which connects the airport to the city's downtown.

Benedormo Airport is also within the vicinity of Almiaro, being only 58 kilometres (36 miles) from downtown Almiaro. The airport is relatively small, with only one runway and passenger numbers of only around 13 million. The airport is primarily used by low-cost Asuran airlines which do not land at Almiaro, and primarily serves as a hub for tourists travelling to the coastal resort of Benedormo to the north of Almiaro. Benedormo Airport is served by the domestic Lombard Rail Network departing from Republic Station. Road networks also link Almiaro to Benedormo, via the A62, with the journey taking an average of 50 minutes by car. Regular bus routes also run to and from Benedormo along the A62.

Seaports

Almiaro is the best connected of all Midrasian cities via sea links, with the city serving as a hub for cruise liners from across Aeia. Several ports exist on both sides of the Bay of Almiaro, with the largest being in New Almiaro within the Old Docklands area. Old Almiaro also has a seaport at Ponte Nuovo. Though this is served by a smaller number of international cruise ships, a significant number of companies charter routes to the south-eastern section of the bay as one of their exclusive destinations. Both the Old and New halves of the bay have marinas hosting yauchts for both public and private use. Regular ferries are also chartered across the bay between New Almiaro, Old Almiaro and Belvedere.

An industrial cargo and small military port also exist in the secluded south-western section of the bay which is not open to the general public and only served by the small number of military and shipping vessels which are based out of Almiaro Bay.