User:Char/sandbox

Red Banner Tribunal Chichipanitl Tlatoloyan | |

|---|---|

| |

| Capital | Tequitinitlan |

| Largest city | Tecolotlan |

| Official languages | Nahuatl |

| Ethnic groups |

|

| Demonym(s) | Zacapine Zacapitec |

| Government | Atlepetl Federation |

• Cihuahuetlatoani | Nochcalima II |

• Chief Secretary | Chicacua Xiomara |

• Cloud President | Tachto Callcalan |

• Earth President | Queya Iluyollo |

| Legislature | Huenecentlaliliztli |

| Mixcalli | |

| Tlalcalli | |

| Formation | |

• Huehuetlatolli Period | 4,400-1300 BCE |

• Colli Period | 1300-17 BCE |

• First Intermediate Period | 17 BCE-21 CE |

• Tlanepantla Period | 21-1634 |

• Second Intermediate Period | 1634-1707 |

• Yancuiliztli Period | 1707-1760 |

• Revolutionary War | 1760-1777 |

• Current Constitution | 1961 |

| Area | |

• Total | 1,845,600 km2 (712,600 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 2021 estimate | |

• 2019 census | 75,785,909 |

• Density | 33.4/km2 (86.5/sq mi) |

| GDP (nominal) | 2019 estimate |

• Total | $2.08 Trillion |

• Per capita | $27,474 |

| HDI (2019) | very high |

| Currency | Amatl |

| Driving side | right |

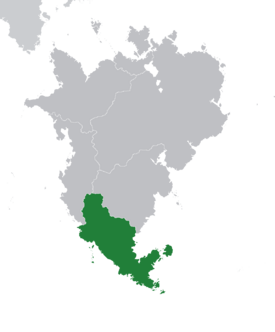

Zacapican, formally the Red Banner Tribunal (Nahuatl: Chichipanitl Tlatoloyan), is an Atlepetl Federation located in southern Oxidentale, bordering Kayahallpa and Yadokawona to the north, the Makrian ocean to the west, the Amictlan ocean to the south and the Ooreqapi ocean to the east. The country is a Tlatoanate organized in a federal stucture broken down into 37 constituent Atlepetls each of which is governed by its own Speaker (Tlatoani), which may be an elected or appointed offical on a flexible basis. At the federal level, Zacapican is governed under a system of diarchy by two rulers, the Great Speaker (Huetlatoani) who weilds primarily judicial power as well as the Chief Secretary who functions similarly to a Prime Minister and likewise serves a chief executive. These co-rulers are appointed by different means, with the Great Speaker often elected by direct nationwide vote from a pool of candidates and serving an indefinite term subject to recall while the Chief Secretary is elected by the deputies of the national Huenecentlaliliztli assembly. This government structure of a judicio-executive diarchy and democratic legislature defines the modern system of the Tlatoanate as it is found both at the national and state level in Zacapican and gives Zacapine democracy and government a charachter dissimilar to other democratic systems found around the world.

Modern Zacapican is shaped by a fusion of its ancient indigeonous traditions of land use, law and governance and the momentous developments of its early modern history that saw a series of revolutionary upheavals and challenges to these old ways that led to conflict and eventually resolution and synethsis of old and new ideas. This was known as the Yancuiliztli period, the Age of Novelties of the 18th century, which saw a period of prolonged conflict between social classes in Zacapican as their roles and standing in society rapidly shifted, culminating in the Zacapine Revolution which was a protacted civil war ending in 1777 with the foundation of the Red Banner Tribunal to govern Zacapican. This revolutionary struggle saw an alliance between the old nobility of the traditional Zacapine empire and the peasantry and commonfolk against the landowning merchant class whose rise to prominence defined and precipitated many of the social changes of the Yancuiliztli period. The aristocracy sought to defeat the upstart merchant elite which had displaced them as the leading caste of society, while the peasantry wished to redress the process of enclosure and privatization of the commons. As a result of the defeat of the merchant elite in this struggle, the aristocracy regained leadership of the country while the land was reorganized under the system of common ownership known as the Calpolli system. Over time, Zacapican under the Red Banner Tribunal developed a system of mass democracy in which the populace gave risen to control executive and legislative power across the country while the old aristocracy now deprived of most of their original authority, consolidated their influence over the judicial system in coexistence with the democratic institutions.

The Zacapine economy is based on the systems of state ownership and usufruct rights laid out in the Calpolli system re-established by the revolution. Under this system, all land within the country belongs to the state, while the local ward or town entity manages its use and acts as a common holding entity for economic activities carried out by its residents. These calpolli workers and economic entities form the backbone of the economy, acting either as individual entities or doing buisness with one another as a group of several calpolli operating together. Although Zacapican operates under a regulated market system, key features of its calpolli-based economy such as democracy in the workplace and collective worker ownership of economic assets relate Zacapican closely to the socialist and syndicalist economies around the world. It is largely for this reason that Zacapican is traditionally aligned with many leftist regimes and with the Kiso pact. The Zacapine economy centers around a developed secondary sector of processing, manufacturing and engineering as well as a significant primary sector represented by widespread agriculture and a limited extraction sector based on iron and coal production. The primary sector of the Zacapine economy is focused primarily on domestic markets for food, products such as biodiesel and sunflower oil, and the intensive demand for steel from the manufacturing sector. Zacapican is a world leader in nuclear technology, and exports ships, naval and military technology as well as a wide array of industrial machines across the world. Internationally, Zacapican maintaigns good relations with powerful nations of varying political leanings such as Pulau Keramat, Latium and North Ottonia while persuing a polcy of detente with its traditional adversary Sante Reze. While in the past Zacapine influence around the world has been relatively limited to regions of the Ooreqapi ocean as part of its competition for regional dominance with Sante Reze, modern times have seen the broadening of Zacapican's international horizons as the nation has become involved in conflicts and alliances across the world, illustrated by its involvement in the Enyaman Civil War and establishment of a military base within its Norumbian ally Wazheganon.

Etymology

The common name Zacapican is derived from the nahuatl zacapi, itself a truncated form of zacapiliztli meaning to harvest or collect grasses, maize or other crops, along with the suffix -can. Thus together Zacapican can be translated as "place where the grass is harvested", a term which may have been assigned to the area in which the ancient migratory nahuas settled as they are believed to have imported sedentary agriculture to the region. Historians believe this name was originally ascribed specifically to the Zacaco grassland region in which the nahuas originally settled, stretching across what is now central and eastern Zacapican, and was only later ascribed to the broader nahua empire which grew to dominate the southern cone of Oxidentale but was always based in the Zacaco plains.

Chichipanitl Tlatoloyan, generally translated as Red Banner Tribunal, is the formal name of the current government and ruling system within the state. Chichipanitl is derived from the nahuatl Panitl meaning flag and Chichiltic denoting a red color, representing the red colored flags used as the rallying symbol of the Red Banner peasant rebellions which resulting in the overthrow of the previous dynasty and installation of the new regime. Tlatoloyan is a more traditional designation, derived from the nahuatl Tlato- meaning a ruling or decision, and the suffix -loyan, and so translates roughly to "place where decisions are made", although it may be more loosely translated as Empire or Tribunal. Those who rule a Tlatoloyan are termed Tlatoani or Heutlatoani, the former translating directly as "decision maker" but more commonly as "Arbiter" or "Speaker", and the latter simply adding the Hue- prefix meaning big, and so translating to "Great Speaker" (or "Great Arbiter"). In Zacapine culture, a hegemonic Tlatoani is considered equivalent to and may often be loosely translated as King and thus the higher Huetlatoani is considered equivalent to can be translated as Emperor but in the modern day both are interpreted through primarily judiciary connotations. Female equivalents of both simply involve the addition of the prefix Cihua-, meaning "woman", resulting in Cihuatlatoani and Cihuahuetlatoani translating directly to "Woman Speaker" and "Woman Great Speaker" respectively.

History

Zacapican possesses an extremely long recorded and archeological history which is made all the more remarkable by its organization into a single cultural and political continuity, although this is in part the result of ancient and more recent historical revisionism which sought to organized at times unrelated dynasties and regimes into a more standardized and rationalized format which fit the contemporary view of history. Nevertheless, it is generally acknowledged that the Zacapine civilization is a single continuum which has existed since at least 2,000 BCE and can be generally understood as being made up of one monolithic empire possessing three phases, the old, the middle and the new empire, which are distinguished from one another by the intervening periods of collapse and subsequent reunification. The period preceding the formation of the empire proper is termed the "predynastic period" as no imperial dynasty governed during this time. The present day is commonly understood to fall within the continuing New Empire period, although a dissenting opinion is that the Red Banner rebellions constitute a third intermediate period and thus the present day should fall within a fourth "Neo-Imperial" period. This view is generally contested and rejected by the academic establishment.

Predynastic Period

Generally, the predynastic period is considered to encompass the entire history of the Nahuas throughout all time prior to the ascension of the first Huetlatoani. This includes the period of pre-Imperial settled nahua civilization in the Zacoco grasslands as well as the preceding epoch of mass migration of the nahua people from Norumbria and further back. However, there remains very little evidence of ancestral migratory Nahuas which would become the Zacapine Nahuas left anywhere outside of Zacapican. The only true evidence tying the ancestral migrators to the northern continent is simply their linguistic relationship to surviving Uto-Aztecan languages which suggest that the migrators cross into Oxidentale prior to the breakup of the land bridge connecting the two regions or immediately thereafter when the crossing was still achievable through the use of primitive boats or rafts. The Nahuas may have been among the last human groups to migrate into Oxidentale and represent one of the newest groups present on the continent before the waves of invasion and migration that would occur in the 1st and 2nd millennium CE by oceangoing Belisarians, Scipians and Ochranites. Many cultural items of the modern and ancient Nahuas of Zacapican appear related to those of the region which would become modern day Mutul in northern Oxidentale, and may well be related practices. Some historians believe this relationship is indicative of a prolonged period in which the Nahua remained in northern Oxidentale and interacted with the groups which are today native to that region, before beginning a second period of migration towards the south of the continent where they reside today. This theory is not well supported by material evidence as the migration occurred prior to 5000 years ago and has left no appreciable archeological record to study, consigning the origins of the austral Nahuas and their relationship to the Norumbrian Uto-Aztecan groups to a permanent condition of vague speculation and mystery.

After the arrival of the Nahuas into the Zacaco plain, archeological evidence begins to mount and evidence of large wooden and stone structures is in abundance. The remains of ancient pyramidal structures, based on earthworks rather than the complex masonry of later such structures, are generally used to indicate the beginning of what is sometimes called the "Zacapitec Kingdom". Around 2,600 BCE the first major settlements are found in the archeological record, along with the first well preserved pictograms and primitive logograms and pictographic or glyph-based scripts develop, although these remain undecipherable in the modern day. Some of these scripts are believed to be the basis of the logophonetic writing system used to record the classical Nahuatl language in the Old Empire period. Zacaco remains to this day relatively fertile and amenable to agriculture, and the idea that Nahuas either introduced agriculture from another region through their migration or else invented their own means of agriculture after settled in the Zacaco grasslands is well supported. The first Nahua city states would emerge on the basis of growing crops on the grasslands, domesticating animals such as the Cochineal beetle used in iconic red dyes, the Zacapine dog, the Rhea as well as several species of camelid native to Oxidentale. Evidence of wars between city states were common at this stage, as the lords of cities would take others as vassals and become the first hegemonic Tlatoani, leading to relatively small number of hegemonic cities dividing up the Zacaco plains among themselves and fighting over the productive lands of the region. Although fertile, the Zacaco lacks many other resources and much of these early civilization was built using wood, mud-bricks or stone with the nahua civilization being definitively in the stone age during this era.

Old Empire

The advent of the first bronze tools and weapons revolutionized the Zacaco plains and the wider southern cone of Oxidentale. Tools fashioned of this metal were malleable and more useful than some of their stone counterparts, and while readily available stone weapons remained effective and were in no short supply, the appeal of bronze in weapons began to rise around 2000 BCE. Coinciding with this new feverish thirst for bronze implements, the hegemonic wars of the predynastic period had come to a head and resulted in the first unification of the Zacaco plains under a single lord, with many other lords arrayed beneath him as lesser nobles. This marks the beginning of the Zacapitec Empire, specifically the Old Empire period, with the ascension of the first Heutlatoani of the first dynasty of the first empire. In this unprecedented time, recourses were sought after more than anything else. The Zacaco grasslands were bountiful and could support several urban centers and a growing population, but the lack of many other recourses had always weighed on the early nahua civilization which had always been forced to trade for other materials with outsiders. This condition was exacerbated by the need for bronze derived from tin and copper, none of which could be found inside the first Huetlatoani's domains. This motivated a period of expansion which would take place over the next four centuries (2,000 - 1,600 BCE) which would lay out the foundation for what would be the Zacapitec empire for many centuries and millennia to come. While the territory captured by the early dynasties of the Old Empire would later be successively lost and regained by later dynasties and indeed later iterations of the same empire, the massive invasion and annexation of completely new territory to the empire which occurred during these 400 years has no parallels in any era of Zacapine history before or since.

The scope of these conquests, especially considering the small size of the original territory of the Zacapican empire at the start of the process, was such that later historians of the late Old Empire and most of the Middle Empire did not believe that they had actually happened, designating the foundational four hundred years of their own empire as a mere legend or myth concocted to glorify and exaggerate a longer period of more gradual expansion. The relatively limited complexity of the early Old Empire, having only primitive cities and armed mostly with stone and wooden weapons, it was thought, simply could not have accomplished the feat of not only conquering such a massive amount of territory but more impressively managing to hold on to the acquired land and subjects for hundreds of years thereafter despite the instability brought about by such rapid expansion. However, mounting evidence from historical and archeological materials have increasingly suggested that the original account of the four hundred year expansion of the Zacapitec empire, long though to be a myth, indeed may be true or at least close to reality. The massive expansion of the Zacapitec empire has parallels in the histories of many other nations and empires all across the world and at different points in history, but it remains a singularly impressive and moreover pivotal feat which established the groundwork for the following 3,600 years of Zacapitec history. One of the more striking aspects which defined the Old Empire period was the effects of metalurgy and bronze weapons on military technology and tactics. Most significantly, the propagation of bronze weapons led to the transition of the spear as a dueling and throwing weapon to a longer, more reliable armament that could be used by formations of infantry working together as opposed to a loosely organized mass of dueling combatants. Infantry trained to fight in tight pike wall formations virtually unassailable from the front became the core of the early imperial army, supported by skirmishers typically armed with throwing spears assisted by atlatl spear throwers which dramatically increased the velocity of such a missile, thus improving their range and penetration. Spears cast from an atlatl were often capable of penetrating Ichcahuipilli armor (cotton armor stuffed with gravel) which could readily defend against arrows from short bows. The military advantages of these formations, themselves enabled by bronze weapons most neighboring tribes could not replicate, gave the Old Empire a distinct military advantage that may have empowered it to rapidly expand from a very small central territory and conquer vast areas of the surrounding lands.

In many ways, the rest of the Old Empire and perhaps the remainder of the empire's history would remain overshadowed by its formative events and earliest dynasties. For the most part, those Huetlatoque that ruled after the great conquests served primarily as administrators and judges, somewhat removed from their foundational purpose as a warrior aristocracy. Nevertheless, the lower rungs of the noble ladder did remain active in martial affairs as an internal security force to keep order in the ancient Nahua cities and to defend them from outside threats, such as the antecedents of modern Kayahallpa to the northwest. The constantly activity of low level military tasks was important for political and social stability, as it maintained a fresh pool of noble blood through the ascension of new noble lines out of lowborn warriors, and the regular exercise of this hereditary warrior caste such that the empire would never lack a powerful warrior lord to take the reigns of leadership and ascend to the throne in case of disaster, unexpected death or incompetence of the current ruler. For this purpose, flower wars would emerge as a tradition of ritualistic warfare wages against internal rebels and disobedient vassals as well as outside threats and neighboring kingdoms and tribes, requiring little investment in military resources and thus carrying little risk unlike a full blown campaign, yet still offering ample opportunity for combat and the benefits this provided to the empire's ruling class. Although much of the population of central and eastern Zacapican would become assimilated into the Nahua culture, much of the empire remained under a state of native rule by local tribes which were subjugated as vassal states to the empire. Eventually, through the decades of the last dynasties of the Old Empire as well as a general decay of the robust systems put in place during the first four centuries, the system of vassal governance across the periphery of the empire broke down. Nevertheless, the consolidation of power under the Old Empire even in the outlying regions had left irreversible effects over the region. Rather than reverting to the pre-imperial state of disparate tribes, the Nahuas of Zacaco as well as the Nahuanized peoples they had left behind in their once-vassal states broke into a small number of large and powerful warring kingdoms, each of which vied for the legacy of the Old Empire in spite of its collapse, bringing about the First Intermediate Period.

First Intermediate Period

The First Intermediate Period was a 140 year period of internal conflict and civil war brought about by a general collapse of central power, a collapse which was perpetuated by a variety of outside reasons such as the revolutionary introduction of mounted cavalry on horses, steel weapons and armor and new military strategies into the region, as well as two disease outbreaks and a prolonged drought. Nevertheless, the Old Empire was ultimately brought down by fundamentally internal problems and animosity between noble factions which struggled and vied for power to the detriment of the peasantry. As the Zacaco city states turned to open conflict against one another, tributaries and vassal states on the outside edges of the empire simply allowed their pacts and treaties with the Zacapitecs to lapse and in some cases even turned on their former overlords to exact revenge or regain territory lost to the empire's advance in previous centuries. Beginning in 119 BCE, the 15th dynasty faced numerous challenges from its former vassal cities, including a rebellion which would soon solidify into the 16th dynasty. While the forces of the surviving 15th dynasty fought the cities in their vicinity in the south Zacaco, the new 16th dynasty consolidated the northern Zacaco and southeast Xallipan regions. The two developed a protracted standoff in their conflict over the Zacaco, falling to ceasefires and temporary peace multiple times as well as securing alliances among the former tributary states in the imperial periphery. Following the transition to the first millennium CE, hostilities between the 15th and upstart 16th dynasties resumed as they vied for unchallenged domination and restoration of the full empire. With their forces committed to the renewed conflicts in the central Zacaco the 16th dynasty was unable to quell an unexpected incursion of the Tiacauteca, a caste of nahua colonists in the hostile semi-arid Xallipan region, which rapidly collapsed the northern garrisons of the 16th dynasty and overran their capital by the year 10. The Tiacauteca proved to be capable warriors, aided by their horses and innovative steel armors and weapons, and were able to rapidly reform themselves into a military caste of noble lineages ruling over the conquered territory of the 16th dynasty and their homelands in Xallipan, which served as a staging area for their assaults on the remnant of the 15th dynasty which fell as well, ushering in the reunification of the Zacaco and the formation of the Middle Empire under the 17th dynasty of mixed Old Empire nobles as well as new Tiacauteca lineages.

Middle Empire

Second Intermediate Period

New Empire

The re-consolidation of Zacapican into the New Empire opened up opportunities for reform and innovation on the long standing traditions of government that had stood for thousands of years by the end of the 16th century. Although Zacapican had never been particularly opposed to outside influence and exchange, the dynasties of the New Empire would prove to be by far the most involved in affairs not only in the immediate surroundings of the southerly nation but around the entire globe. Previous exploration of the surrounding seas and settlement of nearby islands which had taken place during the Middle Empire period would now serve as a springboard for a new naval power in the New Empire. Gunpowder weapons would be introduced and quickly adopted by the Zacapitecs, first in the form of canons and mortars and later in the form of both imported and indigenous man-portable firearms. The 1st and 2nd Dynasties of the New Empire were not necessarily distinct from those that had reigned in the latter days of the Middle Empire, but a distinct shift in their demeanor towards the broader world had developed. Since the turmoil of the recent collapse, ambitions of sweeping territorial expansion had long since died out and the borders of Zacapican generally settled into what they are today. The motive behind this more relaxed foreign policy is the subject of fierce debate, as some suggest that it is the result of more enlightened philosophy and worldly ideas, as well as a revival of classical Zacapitec philosophy and fundamental sciences as part of the Zacapine Renaissance. Others assert that, like the foundational dynasties of the Old and Middle Empires, the early New Empire dynasties had the fresh memories of the bloody intermediate period and were chiefly concerned with pacifying and consolidating the recently reunified Zacapine territories, and therefore would not entertain expansionistic ideas which would generally come to take hold in later dynasties. It is also suggested that the development of technology and the increasingly prosperous Zacapican had eroded the original motivations of the major Zacapine expansions of the past, as the central regions now had reliable access to a very diverse array of recourses for their economic activities, internal trade was prosperous, and the frontiers were well anchored and no longer significantly threatened by outside forces. The combination of these factors would therefore lead to a reduction in expansionism and a disappearance of the prime motivators for the Empire's past wars, resulting in prolonged state of relative peace which would only come to be significantly disturbed by internal social developments brought about by new foreign and domestic ideas and concepts coming into direct diametric conflict with established Zacapine traditions.

First Constitutional Reformation

While the development of mercantile capitalism was well established since long before the beginning of the New Empire period, the advent of industrial capitalism proved to be a significant disruption to the political and economic order of the feudal Zacapine civilization of the time. Pochteca merchants which had previously filled the role of traders of goods began to use their accumulating wealth to challenge and even eclipse the status of Zacapine nobility. The Pochteca most of all advocated the reorganization of Zacapine agriculture which was organized around the ancient Calpolli system and was primarily based on subsistence farming and food production, seeing the communal land holdings and agricultural methods as antiquated, inefficient and most importantly inefficient and thus unprofitable. This growing class of wealthy lowborn individuals and trading families became an increasingly powerful bloc relative to the aristocracy, and soon were influential enough to force the nobility to give concessions including extending privileges to the merchant caste which had previously been reserved to the nobility. This was overall met with little resistance, save from the most powerful nobles including the Huetlatoani, as these stood to loose the most to the rising merchant class while lesser and un-landed nobles were more amenable to working together and gaining from arrangements with the merchants. This dichotomy resulted in a palace coup and the unceremonious end of the 30th Zacapitec dynasty.

What followed was the First Constitutional Reformation which was ratified on the 22nd of February 1706, in which the 31st dynasty was installed under a system of constitutional monarchy which operated as a crowned republic. In effect, this new dynasty, sometimes called the Pochtec regime, was a limited democracy dominated by factions of the agrarian and urban upper class merchants which held stakes in agricultural and proto-industrial ventures, while the monarchs of the 31st dynasty were reduced to figureheads which legitimized the de-facto oligarchy which was beginning to replace the old feudal organization of the empire. In particular, the period following the 1st Reformation was characterized by the general destruction and dismantling of Calpolli towns which collectively owned the land in common. These lands would become privatized and consolidated in a process of enclosure which began to rapidly convert lands which had previously been cultivated by a large number of community members utilized small plots into a small number of large plantations and agricultural estates owned and operated by wealthy Pochtecatl. Following the consolidation of agriculture into the new plantation economy, agricultural yield began to shift towards cash crops intended for export.

In particular, crops which could be used to manufacture textiles in urban work-houses were preferred as this would generate profit upon being sold from the field, upon being sold from the work-house as textiles, and then again upon being transported and sold at a profit overseas. This early industrial economy generated a large amount of wealth for the upper classes of Zacapine society and brought an influx of foreign goods and improvements of technology into the country. However, it also brought about dissatisfaction with the nobility which found themselves increasingly sidelined by the merchant caste which they viewed as undeserving upstarts. Moreover, the agricultural policies of the Pochtec regime generated huge waves of landless peasants which emigrated into the cities looking for work, bringing mass poverty and disorder to these urban centers. Those who remained in the countryside found themselves working on land which was once theirs for poor wages, or simply out of work and facing poverty and starvation without access to the land needed to sustain themselves. While the Pochtec regime was considered a golden age by many due to the rapid advances in technology and wealth, it also brought an unprecedented level of poverty and unrest into the country, unrest which would inevitably boil over into rebellion.

Red Banner Rebellions

The Red Banners emerged gradually and in an organic, often chaotic fashion, but once they began in earnest the rebellions show of a pattern of three major waves. The first of these began slowly and was the most diffuse and poorly organized, occurring between 1756 and 1758 before it was put down by the military. However the unrest did not stop just because the fighters had been defeated, as rioting, disobedience and a nationwide low-level insurgency continued even in the "lulls" of relative peace between the major waves of rebellion. As such, the Red Banner Rebellions (Nahuatl: Panchichiltic Yaohuitl, lit. "Red Banner Uprising") are generally treated as an continual process that did not disappear between the major waves of uprisings, and so it is treated as a single entity known as the Red Banner Revolution. As a concept, the "Red Banner" rebel was born in the turmoil of the 2nd Intermediate Period as an answer to the abuses of the warrior aristocracy during that time, and so by the time of the 18th century the archetype of the peasant rebel sporting a red battle flag was already well known even in the most isolated communities. Riots occurring across the burgeoning slums of the major cities however these were more easily quelled than the rural uprisings, which waged a guerilla war against the empire's military for nearly two years before being defeated in the field and seeing its members largely scatter but continue their attacks on plantations, shipments of merchandise and military installations. Banditry was observed to rise sharply around this period, both as acts of rebellion perpetrated by Red Banner fighters and as opportunistic crimes committed by common criminals taking advantage of the general collapse of law and order.

Peace was short lived after the end of the first wave of uprisings, as the army's heavy handed retaliation and the practice of collective punishment quickly engendered even greater ire among the peasantry and rallied many that had shied away from armed rebellion to the Red Banners, who rose up a second time now empowered by their new recruits. A renewed campaign of guerilla warfare raged across Zacapican from 1760 to 1766 around which time the Red Banners standing forces were once against defeated in the field and forced in hills and badlands from which they continued to harass their enemies and strike at Pochtec plantations within reach of their base areas. The third and final wave of Red Banner uprisings did not occur until 1774, by which point the Red Banners had fully transformed from a loose collection of disgruntled peasants and urban poor to a organized and complex militia which now had veteran fighters who had been practicing guerilla tactics against the government for years or decades. Simultaneously, support for the government was dropping rapidly as the effects of the unresolved civil war exacerbated many of the consequences of the Pochtec economic and political reforms, and the government's heavy handed repression further galvanized the cause of resistance against them. The final straw occurred when a series of major riots once again tore through the many citizens of eastern Zacapican, which the government responded to by attacking the populations of many urban slums with the army directly, pushing not only rioters but the general population out of these difficult to control slum areas of the cities. This proved to be a fatal mistake as a large portion of these now displaced slum residents traveled into the countryside and joined the cause of the Red Banners, triggering the third and final Red Banner uprising.

Now armed with an experienced rebel army, the forces of the Red Banners quickly overran the hinterlands of the Zacaco plain and began to attack the major cities, including the capital Chicomoztoc (modern day Tequitinitlan) which fell to the rebels by 1775. The royal court and the government of the Pochtec regime was evacuated by sea to the western coast of the empire where a temporary capital was established at Tecolotlan. After a period of consolidating forces, a counter-attack began by government forces based in the mountainous western and southern regions against the Red Banners, who's rebel army had successfully captured the most populated regions and productive farmland concentrated on the Zacaco plain. The Pochtec regime was better trained and controlled the navy, maintaining access to high quality foreign weaponry. However, the rebels could now openly recruit in the streets of major cities, and had availed themselves of the contents of many municipal and rural armories as well as a portion of the imperial treasury which was left behind when the capital had been evacuated. Additionally, the Red Banners controlled the most productive agricultural land which they had immediately begun to redistribute to landless peasants and the urban poor as part of their overarching objective of sweeping land reform and the restoration of the Calpolli system. Control of the farmland made it easy for the rebels to supply their army, and furthermore denied the plantation owners among the Pochtecs the ability to raise more funds to pay for their war effort. In capturing the Zacaco region, the rebels had time on their side as the government's war effort could now no longer be sustained indefinitely.

The Pochtec regime's forces remained superior in training and weaponry right up until the end of the war, and they held defensible terrain in the hills and mountains of southern and western Zacapican which made it very difficult to dislodge them and doomed the early Red Banner attacks against them to failure. However, because of the capture of the Zacaco plains the Red Banners no longer needed to completely defeat the regime's military forces in order to win the war. Indeed, while the Pochtec regime retained access to foreign sources of supplies and weapons, their quickly declining finances meant that they needed to recapture parts of rebel held territory if they had any hopes of outlasting the Red Banners. This led to the bloodiest period of the civil war, in which better trained and well equipped Pochtec troops faced off against the determined defense of the Red Banners in their rural garrisons and fortified towns around the edges of Zacaco. Holding a defensive advantage on their own lands, supported by the local population and bolstered by the manpower of the rebellion's cities to the east, the Red Banners maintained their defense for several years.

By 1779, the Pochtec situation had become desperate. Swathes of the army had deserted due to a lack of payment, and some had even defected to the Red Banners as the rebels could now offer more reliable compensation than the government. Exacerbating this problem, the endless attacks against the entrenched peasant armies across the Zacaco plain had brought about massive casualties in many of the best units of the Pochtec army, losses which they were not in a position to replace. In March of 1799, a series of probing attacks broke through the Pochtec lines, revealing major gaps in the government force's defenses. Many among the rebellion were taken aback by the state of the Pochtec army, which they had been massively overestimating as they did not anticipate the degree to which the Pochtec army had deteriorated from the elite and dangerous fighting force it had once been. During the winter of 1799 (June-August), the Red Banner generals prepared their offensives for the following year, stockpiling weapons and supplies. In the summer of 1779-1780, much of the south fell to their campaigning armies, and much of the west had also fallen. The remnant of the Pochtec army continued to fight, holding on to a pocket surrounding the interim Pochtec capital at Tecolotlan, however these forces too fell to the Red Banners by the end of 1780. By the beginning of 1781, all resistance to the forces of the peasant rebellion had been destroyed, and the Red Banners could now dictate their terms unopposed.

Second Constitutional Reformation

Much of 1781 was spent in consolidation and deliberation between various sub factions of the Red Banners. In general, the military leaders and chief figures of the movement and the rebel army were of a poor, peasant background and most were semi-literate or had only recently become literate as part of the rebellion. Very few had interest in holding political power, and this sentiment was echoed by the rank and file of the army as well as the populace which had supported them. The primary aim of the Red Banners had always been land reform, which had now effectively been accomplished by the reformation and re-institution of the new Calpolli system which dissolved the plantations and returned the land to the peasants under a new, more democratic council-based local apparatus. While minor factions within the more educated wing of the Red Banners expressed republican leanings and a desire to implement a national democracy free of castes and old ideas, these movements saw very little support and effectively died out before they could come to be taken seriously. The majority of Red Banner leaders along with the public were content with handing over the rights and responsibilities of high level power back to the old aristocracy, as many nobles disdained the Pochtecs and their reforms and had even sided with the Red Banners in the conflict. Coexistence between a largely ceremonial warrior aristocracy and autonomous peasant communities was believed to be an achievable goal and was readily accepted by the general public and most of the Red Banners. However, concern remained that once the peasants disarmed, they would once again be put down and exploited by the ruling class and their professional military.

Under the proposed new government, power was to be shared between the peasants and the nobility in such a way that the nobility would be able to return to their traditional role at the head of society but the rights and daily lives of the peasantry and the common folk would not be trampled. A system of constitutional monarchy at the city-state and the imperial level was devised, with the new Popular Assembly drawn directly from the population ensuring that the nobles could not simply wield their newly restored powers unchecked and harm the victory of the Red Banners. Similarly, the Red Banner rebels never disarmed and simply reorganized into a National Guard organization that would allow them to re-mobilize should the rights of the peasants ever face a threat be it internal or external. This military force remains separate from the standard professional armed forces under the command of the monarchy to the present day, and represents a fail-safe measure to prevent abuses of power by the nobility. As part of the proposal, new noble lines were enthroned in various city states which had been stripped of nobility by the Pochtecs or placed under ad-hoc governance by rebel forces. Since the last of the 31st dynasty of the New Empire had been destroyed along with the Pochtec regime that supported it, a new noble line was raised to the imperial throne as the 33rd dynasty of Zacapican. The ratification of the proposed new government by the Red Banners and many noble delegates represents the founding moment of the Red Banner Tribunal, and of modern Zacapican.

Geography

The territory of Zacapican is divided into four regions of distinct topographic, climatic and ecological character. These are the Zacaco, Mixtepemec, Xallipan and Aztlacapallco which are situated roughly in the east, west, north and south of the country respectively. The varying environmental factors of these diverse regions of Zacapican inform aspects of human habitation and economic activity which shape the country, its internal politics and its role within the world.

- The Zacaco (lit. "land of grass") region refers to the flat lowlands which cover the eastern quarter of Zacapican, which are primarily covered in grassland with few trees. This region receives regular rainfall and enjoys temperate climate and temperature ranges in both summer and winter, making them fertile and well suited to agriculture. Farmland in the Zacaco region accounts for more than three quarters of the Zacapitec agricultural output and serve as the bread basket for the country and the wider region. This region's food supply as well as the flat, accessible terrain and temperate climate have contributed to the establishment of many urban and industrial centers within the Zacaco region, including the the Zacapitec capital Tequitinitlan. The Zacaco has also been the homeland of the Nahua people since the beginning of recorded history and has served as the social, political and economic center of the Zacapitec empire since its bronze age inception.

- The Mixtepemec (lit. "clouded mountains") is a region characterized and shaped by its mountainous terrain extending north to south along the western edge of Zacapican. Much of the Mixtepemec is composed of a mountain range of the same name with many steep sided snow capped mountains. As much of the Mixtepemec is unsuitable for living or working, the population of the region is highly concentrated in just a few locations along the coast which are relatively flat and have a more temperate maritime climate compared to the colder and less hospitable climate of the mountaintops and isolated valleys. As a result of these factors, the majority of the region's population and economic activity is focused into a single metropolitan center, Tecolotlan, which has grown to outstrip even Tequitinitlan and the other mid-sized cities of the Zacaco plain to become the largest city in Zacapican.

- Xallipan (lit. "banner of sand") is the northern region of Zacapican with a small portion of Makrian coastline along the northern end of the nation's western shore. It ranges from sub-tropical climate in the east close to the Zacaco plains to a more semi-arid, hilly environment of many badlands along the border with Kayahallpa. The sources of many Zacapine rivers flowing through the Zacaco to the southeast originate in vast canyon systems in this northerly region. Xallipan is the second least inhabited of the four geographic regions of Zacapican, and is primarily known for mining activities which are often criticized for the disruption they pose to the delicate ecosystems of the dry hills. Historically, Xallipan has been the frontier of the Zacapitec empire with its rivals to the north, and has been the site of many struggles against those rival powers in centuries past. Because of its history, the region is now home to many monuments and museums exploring the complicated past of these lands as a borderland of empires for many centuries stretching into antiquity. The region's largest urban centers are located in its wetter and more hospitable eastern edge, which also contributes some agricultural activities to the region's economy.

- The Aztlacapallco (lit. "land of the bird's wing") region is covered by cold steppe as well as localized desert biomes, mountains and glaciers such as the large and iconic Xotlatlauhqui (lit. "red legged") glacier. It is also known as the Whale's Fluke because of its two peninsulas resembling the tail fluke of a diving whale. Aztlacapallco occupies the southern portion of Zacapican and is sparsely populated compared to the other regions, having few urban centers. The relatively small economy of this region is based primarily on eco-tourism, and is an internationally renowned vacation destination because of its pristine natural environments.

Besides the four regions of the mainland, Zacapican possesses portions of an archipelago in the south Thalassan ocean known to the Zacapitecs as Michnamanalco (lit. "land of fish selling beyond the water") which has been the subject of past territorial disputes and naval conflicts with Sante Reze and has served as a key port of call in the Zacapitec trans-thalassan trade with Malaio. The climate and biodiversity varies from island to island, from a cold temperate climate in northern islands to an outright polar climate in the southernmost islands of the archipelago. The warmer islands have limited tree cover and host thriving island ecosystems with many unique species that have evolved in isolation, while the colder more southerly islands are typically devoid of trees and covered in snow for much of the year, serving only as important nesting sites for oceangoing birds and marine wildlife. The few human settlements on the Michnamanalco archipelago are civilian ports dedicated to fishing and whaling or military harbors used by the Zacapine navy. The oceanic region of Matlayahualoyan is located between the archipelago and the Whale's Fluke and is a vital region of the country's EEZ as it contributes significantly to the local economies.

Biodiversity

The varied environments of Zacapican house an abundance of life including many unique species found nowhere else. Zacapican is a megadiverse country with an myriad of ecosystems and biomes ranging from sub-tropical forest, wetlands, temperate, dry and cold steppes, mountains, semi-arid and even polar climate regions. The Zacaco region boasts a tremendous degree of diversity in fauna including the Capybara, Zacaco deer, Maned wolf and Ñandu. Mixtepemec is home to the Spectacled bear, the Puma and the Guanaco while Xallipan is known for its many species of scorpions and the Vicuña which often used as a mascot by Zacapine children's media. Aztlacapallco is better known for the species of the surrounding waters, but is nevertheless recognized for such unique species as the Southern river otter and varied avian species such as the Aztlacapalltli woodpecker. Much of the Zacaco, Xallipan and Aztlacapallco regions posses little forest cover and are mostly grasslands, with very few tree species, such as the native Ombu or imported Norumbrian sycamore. The mountainsides and valleys of Mixtepemec are heavily forested by pines and other evergreens such as the native Araucaria tree, and are the main site of logging activities in Zacapican.

In addition to terrestrial life, Zacapican is known for its abundant maritime biology sustained by highly fertile polar waters. An abundance of plankton and krill in Zacapine waters and parts of the surrounding ocean sustains not only a tremendous number and variety of fish species, but also larger and iconic marine species including penguins, seals and whales. The Orca, a common sight on Zacapine shores, is particularly prevalent in local cultures and is regarded as a Zacapitec national symbol. The extremely rich marine ecosystem of Zacapican's waters has sustained an extensive fishing industry particularly within the world-renowned Zacapine Sea Fishery off the country's eastern shore. This fishery specifically has suffered from overfishing historically, but is considered to be in the process of recovering its normal fish stocks thanks to fishing restrictions put in place by the Zacapine government for the express purpose of regenerating the economically important Zacapine Sea Fishery. Historically, many Zacapitec mariners undertook whaling as a means to exploit the abundance of Minke, Humpback, Sei and Cachalot whales. In response to the depletion of these species and the decline in economic demands for baleen and whale oil, whaling of any type has been strictly prohibited by federal law since 1910.

Conservation

The relationship of the peasants and city-dwellers with the land is the single most important political question in the Red Banner Tribunal, thus placing a high importance on the matter of conservation and the management of natural ecosystems. Matters of forestry and resource management regarding wood, pelts, and other goods derived directly from the natural environment have been present in Zacapitec policy long before the Red Banner revolutions, since at least the Middle Empire period. Part of the reforms undertaken by the Red Banners upon taking power was the restoration of Middle Empire era institutions providing for the protection and sustainable exploitation of Zacapican's forests in order to ensure a stable supply of wood for fuel, building and manufacturing in the long term. Restrictions on clearcutting as well as the imposition of a national policy for reforestation and sustainable harvesting practices such as thinning trees for lumber were reinstated in the early 18th century by the Red Banner government and remain in place to this day. Other clear ecological services such as hunted meat, pelts and valuable furs as well as less immediate services such as pollination of crops and fruiting trees by bees have all led to similar protections of specific aspects of the ecosystem which a portion of the peasantry rely on to extract recourses for human benefit. Some of these conservation laws, such as those designed to maintaign a stable population of pelt-bearing animals for reliably lucrative hunts year after year, are regionally specific and are usually implemented at the calpolli level by the very communities which rely on that aspect of the ecosystem for their own sustenance or economic well-being. Others, such as those protecting pollinating insects affect large sections of agriculture or the preservation of important detritovores such as dung beatles or large carrion eating vultures, forestry or other human activities and so are implemented on a national level by federal authorities of the Empire. In both cases, the conservation of the natural environment when it comes to an aspect of the environment that is exploitable for human gain is generally spearheaded and upheld by elements of the public directly affected by the status of those natural recourses who benefit from long term stability and conservation intended to foster continuous long term exploitation of those recourses.

Unlike the conservation of directly beneficial ecological services which has a long history in Zacapican, the preservation of other aspects of the biosphere which are not directly beneficial to humans is less well established particularly where the steps required for natural preservation conflict with technological or infrastructural developments to benefit humans. In particular, attitudes of naturalists and vocal conservationists where highly opposed by public opinion during the period of Zacapitec industrialization in the latter half of the 19th century, during which industrial expansion of the major cities and across the country led to significant damage being inflicted on the surrounding biosphere and ecosystem. The revitalization of some damaged ecosystems deemed salvageable, particularly in and around urban regions, is now considered a priority and has gained in popularity in the 21st century Zacapitec public, along with the general cause of conservation and "good stewardship" over the lands and waters of Zacapican. This has generally led to a number of federal level policies which protect endangered species from being directly hunted or killed off, as well as addressing the problems of habitat destruction. Many nature reserves and national parks have been established by the government in the last 60 years years for the purposes of closing off vulnerable ecosystems and important habitats from any kind of development or anthropogenic disruption, while also creating new tourist attractions out of areas known for their natural beauty.

Government and Politics

The government of the Panchichiltic Tlahtoloyan of Zacapican is a parliamentary constitutional monarchy in which the monarchs of the royal dynasties serve as heads of state, representing the nation to the outside world through diplomacy and military leadership, while the democratically elected legislature and lower tiers of local government effectively governs the internal affairs of the country under the auspices of the Chief Secretary who is formally appointed by the monarch to serve as head of government. Cihuahuetlatoani Nochcalima II is the reigning Empress of Zacapican since her coronation in 2008, having served as Tlatoani of Tecolotlan for 23 years prior. The current Chief Secretary is Chicacua Xiomara, who served briefly under Nochcalima's predecessor as Secretary of Intelligence before returning to his parliamentary career and being elected Chief Secretary for Nochcalima's government for the term beginning in 2015 and has been re-elected in 2020. Under the 1781 constitution of the Panchichiltic Tlahtoloyan, the Chief Secretary is vested with the powers and responsibilities of leading the cabinet and appointing ministers with the approval of the monarch. As such, he is largely responsible for holding executive authority on the federal level and effectively undertakes the day to day administration of the nation in the monarch's stead. Nevertheless, the monarch retains a significant amount of power both as de jure powers which are delegates to elected or appointed officials such as the Chief Secretary and as powers which are still practiced by the monarch, such as command of the military and legislative veto power. The degree to which royal power is exercised varies from monarch to monarch as the monarch wielding authority falls into a number of constitutional grey areas and typically depends on their own personal influence and power base within the government and among the general public. Although young for her station and considered inexperienced, Cihuahuetlatoani Nochcalima II is a popular and well supported figure with many allies in the legislature, making her a relatively powerful monarch and one of the more politically active such figures in recent history.

Legislative authority is vested in the bicameral parliament known as the Tlacacallique (lit. "Houses of the People") or as the Popular Assembly, consisting of an upper house in the House of Clouds (Mixcalli) and a lower house in the House of Earth (Tlallcalli). A total of 3 Cloud Deputies are assigned to each Atlepetl, totaling 111 deputies in the House of Clouds. The selection process of Cloud Deputies varies from state to state depending on local laws, usually involving an election of a pool of candidates from which the state's Tlatoani selects 3 to send to the capital as representatives of that state's interests. Conversely, Earth Deputies are elected by a nationwide general election according to centrally organized voting districts and a ranked choice voting system, all of which is administered by an independent federal agency known as the Bureau of Elections. These deputies are elected directly by the voting public and the number of deputies assigned to each district is dependent on population statistics of a given voting district. It is not required the national voting districts align with state borders, however the Bureau of Elections has maintained this policy of its own volition for purposes of avoiding confusion and conflicting interests, such that a group of Earth Deputies will always directly correspond to a specific group of Cloud Deputies. Per the census which informed the round of elections that same year, 619 Earth Deputies were assigned to all voting districts across Zacapican. Proceedings in each House of the Popular Assembly are led by their respective speaker, who is elected by their corresponding House to hold a ceremonial Tlatoani title. The Tlatoani Mixcalli ("Speaker of the House of Clouds") and the Tlatoani Tlallcalli ("Speaker of the House of Earth") are the only official Tlatoani titles which are elected democratic offices.

Administrative Subdivisions

Zacapican is a federal state made up of 37 Atlepetls operating as the principal political subdivisions within the federal structure of the country, each possessing a state level authority based in the focal (capital) city of that state. The atlepetls are grouped into five overarching regions, which are based on geographic and climate factors and have no administrative or political purpose as they are used largely for the purposes of statistics and other organizational factors on the federal level.

Armed Forces

The Zacapitec Armed Forces (Nahuatl: Yaoquizquemeh Zacapiyotl, lit. "Zacapitec State Armies"), know by its Nahuatl acronym YQZY or informally by the corrupted term "the Ikzi", are made of the Ground Army (Nahuatl: Tlalliyaoquizque or TYQ), Air Army (Nahuatl: Ihuicayaoquizque or IYQ) and the Zacapitec Navy (Nahuatl: Acalchimaltica Yaoquizque or AYQ) and the Military Intelligence Group (Nahuatl: Yaotlapixque Olochtli or YPO). The YQZY and its four branches recognize the Huetlatoani or Cihuahuetlatoani of Zacapican as their Commander in chief and operate under the Secretariat of Defense. These forces are considered to be the professional military body of Zacapican, acting as a standing army in peacetime. YQZY personnel live and work in special military calpolli communities on the grounds of military installations and barracks complexes, and are formally forbidden to practice any other profession for the duration of their service in order to restrict them to training activities and military functions. However, in practice YQZY personnel and recourses are often used by the federal government for civilian functions such as engineering projects, public works and disaster response. In peacetime and under most wartime conditions, the YQZY consist almost entirely of active duty or active reserve personnel.

The Red Banner Guards (Nahuatl: Quitlapiallimeh Panchichiltic or QPC) are a paramilitary force organized around calpolli militias and operate with a command structure entirely separate from the YQZY. The QPC command structure and organization are directly descended from the rebel army of peasants, the eponymous Red Banners, which demobilized at the end of the Red Banner Revolution. The two House Speakers of the Tlacacallique function as the co-commanders in chief of the QPC, while the organization and daily operation of the force is left to the calpolli governing bodies. The QPC function as the main reserve force of the Zacapitec military and double as a gendarmerie in peacetime to serve as law enforcement and security forces for their respective calpolli. Guardsmen of the QPC do not loose their QPC status if they join the YQZY forces, allowing the QPC to be mobilized and lend their manpower to the YQZY during wartime and then returning to their separate QPC status upon the cessation of hostilities to resume their normal duties to the calpollis. Because of this system, the QPC are often considered a part of the Zacapitec military despite their function as a distinct organization with a separate chain of command and leadership.

Economy

Agriculture

The economic and political significance of agriculture in Zacapican is of central importance despite the increasing role of modern industrial activities, thanks in no small part to the central role of agricultural communities in the political system since the Red Banner uprisings. An estimated 9 million Zacapitecs, roughly 15% of the population, are farmers or belong to a farming household according to the 2019 census. All land in Zacapican is publically owned and held by the state, which subsequently divides lands designated for farming into individual parcels which form agricultural calpolli. Under the Zacapitec Calpolli system, usufruct rights for portions of the publically held land are granted to individuals and households to use exclusively or in common. While most often these small family operated farms are held exclusively by that household, the land is owned by the federal state and administered by committee under the local calpolli. A plot of farmland which falls into disuse for a certain period or is voluntarily given up by the rights holder returns as state property to be reissued again to peasants applying for their own rights to use the land. Under the Red Banner constitution, it is illegal for any tax or free to be charged to registered land users for their farmland, however profits from agricultural activities may be taxed by the calpolli, the Atlepetl and the federal government. Because only monetary profits from sale may be taxed, portions of an agricultural calpolli's land may be used to produce food for the farmers' own subsistence for free not accounting for any labor costs. Land use rights once granted do not expire and cannot be revoked so long as the land remains in agricultural use except by criminal penalty for misuse of the land or a separate conviction rendering the rights holder unable or unfit to exercise their use rights. Land rights can be inherited, particularly within the same farming household typically living on the granted lands allowing for inherited multi-generational farms without the need for private land ownership. Direct contribution of agriculture to the GDP has fallen to less than 15% since the waves of industrialization in the 1960s and the rapid expansion of other areas of the national economy and today contributes roughly the equivalent of $247 billion. However, agricultural products both raw and processed make up a significant portion of national exports. These exports have arguably served as the catalyst for the growth and modernization of the Zacapitec economy. Agriculture which considered to include pastoral farming as well as fishing is overseen nationally by the Secretariat of Agriculture, which also oversees the National Agrarian Registry responsible for issuing usufruct rights to farmers.

Agriculture in Zacapican is primarily based on cereals but includes a variety of other crops to maximize yields across Zacapican's many climate regions and soil types. In particular, maize, wheat and barley form the common crops and are used to produce most of the staple foods of the Zacapitec diet. Sunflower seeds, soybeans, sugar cane and grapes are also cultivated both for food and as the base elements of processed goods such as sunflower and soybean oil, refined sugar and wine. Orchards of lemon, orange and apple trees are also common particularly in the Zacaco region. Zacapican is the world's largest producer of Ca'a tea, which is a culturally significant beverage in the country but has also become popular in foreign markets. A significant portion of the agricultural sector in Zacapican is devoted to livestock, especially in less fertile steppe ecosystems such as those found in the Aztlacapallco region which are poorly suited for crop cultivation. Cattle are the primary livestock in Zacapican and are raised primarily for beef, desired as a dietary staple across much of the country as well as an important export since the advent of refrigeration. Poultry such as chicken and turkey are also raised, typically alongside crop fields as part of the average farmstead, for both eggs and meat. Historically, the pastoral regions of Zacapican also hosted large herds of sheep which produced wool for export. This aspect of pastoral agriculture has largely faded, as sheep are now far less common in Zacapican and are raised primarily for mutton.

Manufacturing

Heavy industry and industrial manufacturing has been the cornerstone of the Zacapitec economy since a wave of modernization and industrialization swept the country in the 1960s. The manufacturing sector is the product of a massive and ongoing investment by the state and the national treasury, which has been focused not on any particular finished product or process, but rather on the general capability to establish industries in new and varied sectors as they emerge or become relevant. This has led to a focus on industrial production of machinery and other industrial equipment, defined by influential Zacapitec economist Calcui Xipil as "machines to build machines", alongside the industries for the processing and mass production of steel and other key materials required for many kinds of manufacturing and construction such as glass, plastic, concrete and cement. As a result of this industrial policy, Zacapican lacks many world renowned producers of finished goods but is well a well established exporter of components used in almost all industries, securing Zacapican a spot in the global supply chain. Aerospace, automotive, elecronics and paper industries are represented in the Zacapitec economy, but are either local subsidiaries of international companies or are domestic firms which largely confined to markets within Zacapican as they rely on protective tariffs to operate.

Under the Calpolli systems, factories, workhouses and other manufacturing facilities operate in a similar system to that of the agricultural calpolli, with some minor differences. All industrial facilities remain publically owned, but cannot be individually granted for use to each worker or worker's household due to economies of scale and their effect on the workplace, putting the facility under the control of the calpolli community the workers belong to which holds and exercises their use rights on their behalf. Because the industrial calpolli is no longer based on the management of individual use rights for fixed assets which can be revoked or granted to others freely, manufacturing assets as well as other enterprises of a non-agricultural nature are effectively the property of the local calpolli or in some cases the atlepetl above the calpolli which uses it. In this way, the Calpolli system when applied beyond the agricultural context creates communities specialized in a particular industry or more often a particular element of an industry, in which all or most of the working adults of that community participate in that specialized economic role by way of the publically owned factory or work facility which forms the economic centerpiece of the community. These calpolli units often serve as individual links in a supply chain, with multiple adjacent calpolli entities each operating facilities which compliment each other or add complexity and value to a product in a linear sequence from one calpolli to the next. The industrial aspects of these communities, such matters concerning the output, technical processes or quality of a manufactured product, or broader economic concerns affecting the factories held by industrial calpolli are governed by the Secretariat of Trade and Industry. Human aspects of the manufacturing process, such as workplace safety, working conditions and requirements or duties regarding the workers are governed by the Secretariat of Labor. These two government bodies, along with the Secretariat of Transportation, are known as the "Industrial Trifecta" and are responsible for administering the bulk of the Zacapitec economy.

Energy

The energy infrastructure of Zacapican has undergone several transformative processes since the electrification of the country at the turn of the 20th century. Initially, the nascent national power grid was supplied entirely by coal power plants, although in a short amount of time minor rivers were being dammed for hydroelectric power. This status quo remained in place until the massive industrialization of the country in the 1960s, shortly after which federal authorities began experimenting with alternative sources of power in response to the generally negative view of the public towards coal power which was somewhat exacerbated by the proliferation of factories and other heavy industrial centers. Hydroelectric power was expanded first, with new dams built and many old ones undergoing retrofits or in some cases being completely rebuilt. In the following decades of the late 20th century, domestically manufactured wind turbines were being installed in wind farms across the country. Early solar power initiatives consisted of thermal solar plants, which have been largely discontinued in favor of solar plants based on photovoltaic cells as the technology has become cheaper and contrasts favorably with the costlier and technically complex thermal solar plants. The most recent addition to the Zacapitec energy sector is nuclear power which has been introduced recently and is not yet widespread in the country. Only two nuclear power stations exist in Zacapican, the first being the large Ahuizotzi power plant completed in 2014 which serves the considerable energy demands of the Tecolotlan metropolitan area, while Yatlaxapan power plant intended to serve the Tequitinitlan area is still under construction. Electric power is considered a public service nationwide guaranteed by the government and provided by the Secretariat of Energy and its subsidiary organizations. Power plants and other electric infrastructure are operated by the federal government and provided directly to the individual users bypassing the atlepetl and calpolli tiers of government. A controversial electricity tax is levied at the federal level, and contributes directly to the national treasury. This tax charges a flat rate to each household connected to the national grid rather than charging per kilowatt hour, although tax exemptions have been implemented to provide relief under certain conditions to the moderately high tax rate charged for electricity. These exemptions were put in place in response to criticism of the tax which claimed that it would disproportionally affect poorer households which typically use less electricity in their daily lives, while officials have stated in defense of the tax that when adjusted for purchasing power and inflation, the monetary cost of the tax for a Zacapitec would still be less than the electricity bills paid to private companies for the same amount of power usage in foreign countries, arguing that even with the tax being levied power is still cheaper in Zacapican than in most other developed countries.

Infrastructure

In Zacapican, there are 179 airports with paved runways including 22 international airports, out of over 1000 airports and local airfields across the country. Air travel is the primary means to transportation to and from many Zacapitec territories such as the outlying islands of the Aztlacapallco region, the islands of the Michnamanalco archipelago and many particularly isolated locations in the inaccessible mountains and highlands across Aztlacapallco, Xallipan and the Mixtepemec. Itzcoatl International Airport serving the Tequitinitlan metropolitan area is the largest and busiest of Zacapican's airports since its opening in 1941. Tequitinitlan serves as the central hub for a network of roadways consisting of 71,361 km (44,342 miles) of paved roads out of roughly 255,000 km (158,450 miles) of total roadways. A large number of expressways were established in the mid 20th century connecting many of the major Atlepetl capital cities, the national capital and several sub Atlepetl grade urban centers especially across the Zacaco region and along the coastal strip of western Mixtepemec. The inadequacy of these expressways and modern road systems has been noted, specifically citing poorly maintained roads, which may have contributed to the increasing demand for rail transportation particularly between major urban centers.

The Zacapitec public transportation system is organized around the National Transportation Service (Nahuatl: Cecnitlacayoh Tlacazazacalo Atlepetequipanoliztli) known by the nahuatl acronym CTA which serves as the standardized national transportation system governing most forms of rail transit as well as some bus services particularly those in the major cities. CTA was formed in the year 1960 through the unification of over 200 individual light rail, commuter rail, heavy rail, inter-city rail, tram and bus networks which existed within and between numerous Atlepetl level transit authorities. While many mid-sized cities had in the previous decades developed extensive public transportation systems of their own to keep up with a growing population and more interconnected economy, the federal government found that such systems in very large cities such as Tecolotlan and Tequitinitlan were underdeveloped, and moreover that connectivity between city-state level territories was in a poor state. Under the CTA, all levels of a city's transportation scheme are integrated with one another and linked into regional and national transportation networks, allowing for seamless transition from local light rail and bus systems to city-wide and regional heavy rail as well as the national high-speed rail network. CTA fares vary depending on the number and type of connecting services involved in any one journey and are usually specific to the atlepetl, but are typically flat fares for subway, light rail and bus systems within a city or town, switching to a distance based fare for regional, inter-regional and national systems such as the high speed rail network. With maintenance and extensive network expansions as well as heavily subsidized fares, the NAT has operated at a net loss since its inception and requires a yearly subsidy from the national treasury to balance its internal budget. Public transportation and specifically the massive expansion and integration of transit systems under the CTA is correlated with the so called Second Wave of the 1970s, an period of explosive economic growth in the cities of Zacapican which occurred several years after the initial economic boom of the industrialization years of the 1960s had slowed down, particularly leading to great stimulation and growth of the economy in previously isolated suburban areas which became connected to metropolitan transit networks. The CTA operates as a subordinate organization to the Secretariat of Transportation and is considered a part of the federal government.

Communication law in Zacapican generally follows the trend of nationally operated and regulated public services. Internet services operates under a public option system, in which residents or visitors in Zacapican have the option of using the Zacapitec state ISP, the National Public Telecommunicatins Service also known as Cecnitlacayoh Nuhhuian Macho Huehcacaquiztli Atlepetequipanoliztli or CNMHA or their choice of alternatives including community owned local providers or even domestic subsidiaries of foreign providers. CNMHA operates as the state owned telecommunications company and is also the sole provider of fixedline and mobile telephone service in Zacapican, in addition to providing much of the communications infrastructure used in digital and analog TV broadcasting. As such, major Zacapitec TV networks such as the news network Tzatzihua broadcast using CNMHA's telecoms infrastructure. A majority, however not a totality, of Zacapican's communications infrastructure is owned and operated by CNMHA, which itself operates under the auspices of the Secretariat of Communication. CNMHA has been accused of carrying out censorship of the internet on behalf of the Zacapitec government, however accusations of censorship do not extend to CNMHA's other services which are considered to critics to be more openly run and lacking apparent censorship. Spokespeople of CNMHA and the government have independently asserted the state owned company's adherence to the principle of net neutrality, claiming that the ISP does not block or restrict access to content of any kind except in collaboration with the government when shutting down access to sites that are in clear violation of criminal law. Similar to its transportation counterpart in the CTA, CNMHA has rarely seen a year of net profit and generally looses money due to its low prices on the user end and high costs of relatively high end infrastructure. Both CTA and CNMHA as state owned companies are considered to be maintaining public infrastructure at a loss using tax revenue to make up the difference, with the understanding that the vital services these companies provide in the name of the state foster economic growth and prosperity that, if quantified, would be greater than the subsidy paid by the national treasury to each of these companies in a given year.

Demographics

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1919 | 33,124,894 | — |

| 1924 | 33,974,251 | +2.6% |

| 1929 | 35,025,002 | +3.1% |

| 1934 | 36,084,261 | +3.0% |

| 1939 | 36,820,675 | +2.0% |

| 1944 | 38,354,870 | +4.2% |

| 1949 | 39,541,104 | +3.1% |

| 1954 | 41,188,651 | +4.2% |

| 1959 | 43,817,714 | +6.4% |

| 1964 | 46,172,513 | +5.4% |

| 1969 | 48,348,182 | +4.7% |

| 1974 | 50,362,690 | +4.2% |

| 1979 | 51,760,216 | +2.8% |

| 1984 | 53,361,048 | +3.1% |

| 1989 | 54,729,281 | +2.6% |