Wazheganon

Asherionic Federation of Wazheganon 10 official names

| |||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Motto: «ᒪᐊᓄᐅ ᐎᐃᑲᐊᓂᓯᐣᑌᐎᓇᐣ ᒪᐊᒮ-ᐃᓇᐎᓯᐗᐠ᙮» «Månø wīkånisindewinan måmwi-inawiziwag.» ("Let there be brotherhood among all nations.") | |||||||||||||||||||

| Anthem: ᐊᓂᒥᑮ-ᓇᑲᒧᓐ Animikī-nagamon Thunderbird Song | |||||||||||||||||||

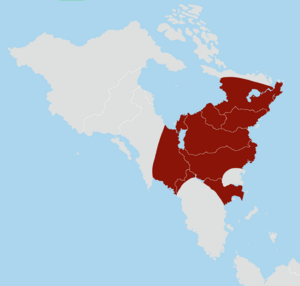

Location of Wazheganon on Earth. Claimed territory in light green, other members of the Norumbian People's Alliance in blue. | |||||||||||||||||||

Political Map of Wazheganon | |||||||||||||||||||

| Capital | Mawosåw [a] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Largest city | Jabwygan | ||||||||||||||||||

| Official languages | none at the federal level [b] | ||||||||||||||||||

| Recognised national languages | |||||||||||||||||||

| Ethnic groups (2020) | |||||||||||||||||||

| Religion | List of religions

| ||||||||||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Wazhenaby Wazhenabyg (plural) Wazhe(g) (colloquial) Laker (colloquial) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Government | Federated communalist semi-direct democracy | ||||||||||||||||||

• Baswenåzhi | Omizakamigokwy Ashagi | ||||||||||||||||||

• Bemångik | Doshya Wolf | ||||||||||||||||||

• Ashahiga | Hokorohiga Chonaky | ||||||||||||||||||

| Legislature | Federate Congress | ||||||||||||||||||

| Grand Council | |||||||||||||||||||

| House of Nations | |||||||||||||||||||

| Formation | |||||||||||||||||||

| c. 1200 | |||||||||||||||||||

| 1621 CE | |||||||||||||||||||

• Federated Republics of Great Norumbia | 8 July, 1802 CE | ||||||||||||||||||

• Asherionic Federation of Wazheganon | 8 July, 1823 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Area | |||||||||||||||||||

• Total area | 1,854,816 km2 (716,148 sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

• Water (%) | 14 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||||||||||

• 2020 census | 47,703,216 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Density | 25.71/km2 (66.6/sq mi) | ||||||||||||||||||

| GDP (nominal) | 2020 estimate | ||||||||||||||||||

• Total | $1,327,580,501,280 | ||||||||||||||||||

• Per capita | $27,830 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Gini (2015) | low | ||||||||||||||||||

| HDI (2015) | very high | ||||||||||||||||||

| Currency | asha (ᔕ, W₳) | ||||||||||||||||||

| Time zone | UTC -6 to -7 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Date format | dd/mm/yyyy | ||||||||||||||||||

| Driving side | right | ||||||||||||||||||

| Calling code | +64 | ||||||||||||||||||

| Internet TLD | .wz | ||||||||||||||||||

Wazheganon (/wɑːˈʒɛɡənɔːn/ wah-ZHAY-guh-nun, -ZHEH-,-NAWN), officially the Asherionic Federation of Wazheganon, sometimes colloquially referred to as the Wazhenaby Federation, is a country in northeastern Norumbia. Its 10 commonwealths cover a peninsula of approximately 1,854,816 square kilometers (716,148 square miles), situated between the Sea of Dakmoor, across from Ghant, in the north and northeast, the Salacian Ocean in the southeast, and Winivere Bay in the west. The country shares land and maritime borders with Awasin in the southwest and Rökkurlynd in the southeast. Most of Wazheganon's population of 47,703,216 people live in the watershed surrounding the Gishigami lake system and the river Gijizībi. The capital of Wazheganon is Mawosåw, while its largest city is Jabwygan. Other major urban areas include Viktorya, Menahok, Dodagon, and Mishkodaga. Wazheganon is a highly multicultural society, with many different ethnic groups of Norumbian, Belisarian, and Ochranese descent.

Various indigenous peoples have inhabited what is now Wazheganon since the last ice age, with the first evidence of human habitation dating back to approximately 15,000 BCE. The earliest written records from Wazheganon are found on birchbark scrolls from the 6th century CE, and contact across the Sea of Dakmoor can be attested to as early as 300 CE. For much of history, indigenous peoples organized themselves in loose tribal structures. The first major polity in the region was the Seven Fires Council, a confederation of republics formed in the early 13th century in order to combat the incursion of Mniyapi-speaking tribes from the south. This alliance disintegrated by the mid-1500s, leading to the Great Lake War between the republics from 1574 to 1591. Following the devastation from this conflict, Otomarcan colonizers on the east coast began expanding inland, forcibly displacing local populations and repopulating newly conquered lands with settlers from linguistic and religious minorities. In response to the previous century's escalating political, military, and economic turmoil, the Maize Revolution swept across the region, replacing hereditary, patriarchal socio-political structure of many tribes with matriarchal, democratic systems and organizing the republics into the Iron Confederacy, which successfully limited Otomarcan expansion. Sudden losses in Norumbia compounded with disputes following the Battle of the Salacian, leading the Otomarcan colonies to declare independence in 1731. Endemic warfare between the Iron Confederacy and settler-states continued, culminating in the Asherionic Wars from 1798-1823, in which a pan-indigenist, proto-socialist revolution led to the brief conquest of much of eastern Norumbia and the subsequent creation of the modern state of Wazheganon.

Wazheganon is a libertarian socialist federation in the communalist tradition, consisting of 1,152 autonomous communes, 10 sovereign republics, and 2 federal districts with a bicameral semi-presidential system which divides executive powers among a triumvirate. It maintains a decentralized socialist economy in which basic needs have been decommodified and all firms are either employee-owned, community-owned, or state-operated. Major industries and products include foodstuffs, forest products, commercial vehicles, industrial machinery, telecommunications, and tourism. Wazheganon ranks highly in international measurements of political freedoms, government transparency, education, and quality of life. It is a member of several international organizations and alliances, including the Forum of Nations, Joint Space Agency, Kiso Pact, Global Observatory of Labor, Society for Material, Economic and Social Aid, Common Congress of Oxidentale and Norumbia, Norumbian Peoples' Alliance, and Osawanon Community.

Etymology

The word Wazheganon first appeared in the written record of Otomarcan colonists in the mid-1700s as "Washagagan", describing the borderlands in the country's northeast where violence between indigenous tribes and colonizers was worst. While there remains some contention among linguists as to its origin, the most widely accepted theory is that it derives from the Middle Dowazhabymowin phrase "wåzhahå jīgi-zåga'igan" («ᐙᔕᐦᐋ ᒌᑭ-ᓵᑲ'ᐃᑲᓐ»), which translates to "bay by the lake", likely in reference to either Geshabegīak (the bay at the mouth of the river Gijizībi) or Adaluka (the southeastern sister-lake to Gishigami which, despite being a hydrologically separate lake, has historically been treated as a bay due to the flat, narrow dividing isthmus), both of which were the focus of intense colonial struggle.

The contemporary Dowazhabymowin name for the country, Mishizåga'igananwakī (ᒥᔑᓴᐊᑲ'ᐃᑲᓇᓋᑭᐃ), literally "Big Lake Country", a version of which first emerged in the 15th century in reference to the Gishigami basin, is held up as an alternative origin for the modern name. Proponents believe that a cursive "Mi" was misinterpreted as "Wa" in colonial correspondences, leading to the transitional "Washizåganawak" which appears (albeit rarely) in some early colonial documents, until finally transitioning into "Washagagan" and then "Wazheganon".

Geography

Wazheganon comprises the northeastern corner of Norumbia, occupying approximately 1,854,816 square kilometers (716,148 square miles) lying roughly between the latitudes 48° and 72°N and longitudes 76° and 103°W. Despite its position and cool climate, no part of mainland Wazheganon lies above the Boreic Circle; the only part of Wazheganon to extend so far north are the islands of Wanwøsenaki and Ashahigaminisi. Wazheganon is situated on the northern end of Norumbia's northeastern peninsula, surrounded by Winivere Bay to the west, the Sea of Dakmoor across from Ghant to the north, and the Salacian Ocean in the east. It shares land and maritime borders with Awasin in the southwest and Rökkurlynd in the southeast.

The geography of Wazheganon is dominated by a series of freshwater lakes and rivers called the Gishigamig (ᑭᒋᑲᒥ'ᐃᓐ), literally meaning "Great/Big Lakes", which connect to the Sea of Dakmoor via the river Gijizībi. They consist of, in order of largest to smallest: Gishigami (ᑲᒉᒐᒻ) [d], Ginøgama (ᑭᓄᐅᑲᒪ), and Adaluka (ᐊᑕᓪuᑲ); the southern bay of Gishigami is called Nīnahaty (ᓂᐃᓇᐦᐊᑕᔾ) and often treated as a separate lake, despite not being an independent body of water. Garekondī (ᑲᕃᑯᓐᑎᐃ), a lake along the Gijizībi, is also usually included among the Gishigamig. Gishigami is the second largest lake in Norumbia, with a surface area of approximately 64,352 square kilometers (24,846 square miles), and one of the deepest lakes in the world with a maximum depth of 706 meters (2,316 feet). The collective watershed of the Gishigamig encompasses the majority of mainland Wazheganon, with thousands of rivers flowing into the lakes. The longest of these is the Mineshøsh River, which flows over 1,133 kilometers (704 miles) from northern Oskåtosa to Nīnahaty. The Gishigamig flow out via the Gijizībi into Geshabegīak, the largest estuary in the world. Not including Garekondī, the Gijizībi is one of the widest rivers in the world, standing 40 kilometers (25 miles) at its widest point. Not including the estuary, the Gijizībi is approximately 252 kilometers (157 miles) long.

Regions of Wazheganon that are not part of the Gishigamig basin are typically separated from it by hills and mountains. The eastern coast is primarily flat and rocky, characterized by many inlets and islands, most notably Hesebuk Bay. The Oskandowa Mountains run along the east coast from Jajīgagī in the north to Weskoki in the south. They transition into the larger and more rugged Osawanon Mountains along the Weskoki-Jenasha border. The Osawanons then go both south into Rökkurlynd and west along the southern border. The Gerøgera Mountains run along the west coast from northern Oskåtosa into Awasin, forming the easternmost segment of the Winivere Cordillera. The highest mountain in the Gerøgeras, Dolidak, is also the highest peak in Wazheganon at 5959 meters. However, Dolidak and the surrounding Hezazaga Range are extreme outliers amongst the Gerøgeras, with most other peaks in the country not rising much beyond 4000 meters.

Climate

Wazheganon is dominated by a humid continental climate, of the hot-summer variety on the east coast and the warm-summer variety in the interior. Cold air from the Boreic and warm air from the Kayamuca stream produce dynamic weather patterns. The Gishigamig have a strong moderating effect on much of the region, but heavy and frequent lake-effect snow is common in the winters, where snow can remain on the ground for as long as six months. Summers are typically warm and mild, although heatwaves are not uncommon. The region around the Gishigamig hosts fertile farmland and extensive forests, ranging from the Lotharian forests on the east coast, to the Gishigamig Northwoods in the interior, to extensive boreal forest in the north.

Wazheganon's northern regions have a subboreal climate which transitions to a tundra zone along the northern coast and Boreic islands. Along with boreal forests, cold wetlands, extensive lakes, and rolling hills dot the landscape. Some of Wazheganon's most iconic megafauna, such as the pygmy forest mastodon greater hodag, and lake sloth are found in the north. The west coast of the country is part of the Winivere Cordillera, a sweeping, interconnected series of mountain ranges that spans almost the entire coastline of Winivere Bay. In Wazheganon, this region features a subpolar oceanic climate along the coast, with hemiboreal conditions found in the Gerøgera Mountains.

Throughout the country, ecosystems have been carefully managed by local experts for centuries or even millennia. Regular controlled burns and monitoring of flora and fauna are done to maintain a mosaic of forests and prairies, much of which is simultaneously used for silviculture and permaculture.

- Pygmy forest mastodon.png

The pygmy forest mastodon, once critically endangered, has recovered in the past century and is an iconic mascot of northern Wazheganon.

Cranes taking flight in a marsh in southern Meskosin.

History

Evidence of human habitation in what is now Wazheganon dates back to at least 15,000 BCE. Archaeological records suggest that trade networks spanning the Gishigamig basin and coast of Winivere Bay were common as early as 1000 BCE, with evidence of trade as far away as modern day Enyama and Serkonos. The indigenous peoples of what is now Wazheganon, primarily speakers of Kadowakan languages, lived in agricultural settlements that practiced permaculture and supplemented their food with hunting and foraging. These early peoples were characterized to neighbors by their large canoes, extensive use of copper tools, and domestication of madimoseg for meat, milk, and wepïwy. The term "Wazhenaby", which did not enter regular use until the late 1800s, is used historiographically to refer to anything historically originating from the area of the modern country.

The first large regional polities appeared around 400 CE, consisting of clans which democratically governed together based on consensus, which in turn confederated under popularly-selected councils, typically forming along linguistic lines. These bands oversaw the distribution of resources and labor in a given area, coordinating both urban public works projects and the management of local ecosystems for permacultural and hunting purposes, as well as organizing war parties against other bands. While these confederacies only exerted influence over relatively small local regions, a growing body of historical evidence depicts a polity spanning much of modern Wazheganon 7th to 9th centuries. This entity, a sort of "shamandom", was a first-order regime which lacked the characteristics of a state, instead being a network of religious organizations which enjoyed popular support, apparently towards the end of constructing the archaeological site of Manidøbå near modern Mishkodaga. Manidøbå served as a pilgrimage site and spiritual center, maintained by voluntary tithes from confederacies throughout modern Wazheganon, who would in turn benefit from the religious expertise of Manidøbå's medicinemen and utilize its facilities to experience revelatory visions.

Seven Fires Council

Serkonian language speakers began migrating northwards into the region around 900 CE, coinciding with the Years of Ash in Mniohuta which triggered a migration of Mniyapi-language speakers as well.

This encroachment by foreign tribes spurred the region's Kadowakan inhabitants, utilizing the relationships and communications network originally formulated by Manidøbå, to join together to protect their hunting grounds and farmland, forming the Seven Fires Council around 1100 CE. Named for its seven founding tribes (the Dowazhabyg, Hesinapek, Jajigak, Jīgbīnik, Meshkodeg, Michikawak, and Wīkwegameg), it fostered connectivity between Kadowakan groups and allowed them to focus outwards towards the migrating Hazīragra and Odolekyga tribes. Although these wars were generally limited in scope and duration, focused around protecting specific areas or avenging deaths, rather than ousting the invading tribes altogether, the military necessities of this period led to the innovations of ironworking ("skipping" the bronze stage common in other parts of the world) and a predecessor to the modern Dowazhabyg syllabery. Over time, many northern tribes would be assimilated into the Dowazhabyg, leading them to become the largest and farthest-ranging ethnic group in Wazheganon.

This period also saw the first sustained, large-scale contact between northeast Norumbia and expeditions from Ghant and western Belisaria. Although Jajīgak and Dowazhaby fishermen and traders had been making frequent trips to Ghant since at least the 10th century CE, the first major trans-oceanic expeditions on both sides of the Salacian Ocean did not occur until the 13th century. The Ghantish port of Onmutu was a great nexus of Norumbian, Ghantish, and Belisarian sailors, where merchants first became interested in the furs, crops, and trinkets offered by Wazhenabyg. Ghant, in particular the Kingdom of Dakmoor, became a popular destination for mådåd. the ritualistic journey of bachelors seeking a new home away from their families, leading to a significant Kadowakan minority. In turn, several Haratago groups, upon their exodus from the Ghantish mainland, chose to settle in northeastern Wazheganon, leading to the eventual birth of the Wazheganon#Ethnic groups|Luronuwi creole group.

As time went on, traders and adventurers from western Belisaria, namely Aldanglea Keuland, and especially the Allamunnic-speaking regions of Otomarca, established small trading outposts and ports in a coastal network stretching from Rökkurlynd to Enyama. Chief among these in Wazheganon was the city of Almarstað (modern day Amested), founded in 1159. Initial successes here, as well as promises of fertile soil and plentiful furs, inspired more voyagers from northwestern Belisaria to settle in this area, leading to clashes with local groups over land and resources. This caused the Hesinapek to appeal to the Seven Fires Council for military aid; in what would become known as the Piedmont War, a coalition force swept through the Ryter Valley in modern day Mågdeland in 1312, pillaging settlements and relegating Belisarian activity to the port of Almarstað and similar minor trading ports. Displaced Belisarians would eventually congregate further south in modern day Rökkurlynd.

This brief, decisive war solidified the Council's status as a regional hegemon, with the Dowazhaby Republic at its head producing an outsized political and cultural influence. Gradually, the Jīgbīnik, Meshkodeg, and Wīkwegameg were assimilated into the Dowazhabyg, at first informally through marriage and cultural osmosis, and then eventually formally with their integration as entirely new clans within the Dowazhabyg. This period also saw the spread of Dowazhabymowin as the lingua franca of the region.

Sporadic, endemic warfare would continue between indigenous nations and Belisarian settlers across northeast Norumbia. In what is now Awasin, the Kadowakan and Mniyapi worlds met in ritualistic battles over rights to seasonal buffalo hunt. Although domestic madimoseg were raised for meat and leather in northern Wazheganon, they would not become a major resource until the breeding programs of the late 1800s proliferated them throughout the region, making buffalo a valuable resource for all regional powers. The Wåyachawich, on the west coast, gradually became the most prominent representative of Seven Fires Council interests in these "buffalo meets", while the Hazīragra alternated between secondary participants and saboteurs of Wåyachawich efforts.

Iron Confederacy

A perennial point of contention within the Seven Fires Council was interaction with non-Kadowakan groups. Traditionally seen as outsiders to the greater Kadowakan "family", the Odoleky and Hazīra nations and surrounding Serkonian/Mniyapi groups were variously treated as ritualistic enemies and uneasy gatekeepers to long-range trade routes. This compounded with the two competing political currents of the time - the more patriarchal, personalist institutions found in central Wazheganon, which favored competition with outsiders, and the more matriarchal, deliberative institutions found on the east coast, which favored cooperation with outsiders.

By the mid-1500s, gunpowder weapons began to be introduced to the region and were enthusiastically adopted en mass by most nations. This exacerbated and escalated the endemic conflict between groups, eventually leading to calls among Dowazhabyg and Michikawak for the complete removal of non-Kadowakan groups from Wazheganon. Fundamentally disagreeing with this, the Jajigak and Hesinapek blocked attempts to mobilize forces. This gridlock quickly escalated, eventually leading to a civil war within the Seven Fires Council which would come to be known as the Great Lake War, a vicious conflict lasting from 1565-1593, which saw unprecedented mobilization and bloodshed. The "Foresters", consisting of the Hesinapek, Odolekyga, and Hazīragra, fought against the "Coldburners", consisting of the Dowazhabyg, Michikawak, and Wåyachawich; the Jajigak attempted to remain neutral, but would eventually join the Coldburners. The war, already deadly due to the combination of new technology with outdated tactics, was further exacerbated by a prolonged drought-caused famine. Altogether, this period is believed to have led to the death of upwards of 20-30% of the population of the region. In the end, the Great Lake War had no clear winner. Many smaller tribes were completely wiped out as a result of disease and conflict.

There was no clear winner in the Great Lake War. Hostilities nominally ceased in 1593 but skirmishes and mourning wars continued between the two sides, leaving most republics economically devestated and politically paralyzed.

Seizing upon this moment of weakness, Otomarca, which had come to rule many of the minor Belisarian trade ports on the east coast of Wazheganon, began encroaching on indigenous territory. Displacing large coastal populations, the Otomarcans seized large swaths of land from the Odolekyga, Hesinapek, and Jajijak in the Oskandowa Wars from 1609-1624, ensuring a permanent, powerful position in the region. This area was systematically resettled using ethnic and religious minorities from throughout western Belisaria, the forefathers of the modern Umbiers. This war and accompanying forced migrations further destabilized the indigenous republics, and resulted in widespread cultural and political revolution. Hereditary chiefs and the clan-based division of labor were disposed of in what became known as the Maize Revolution, and power was placed in the hands of elected chiefs and councils of clan mothers, with clans becoming matrilineal in most places. The eventual result of this upheaval was the Great Peace of Mawosåw, a treaty signed on September 23rd, 1633, in which newly elected leaders from 23 republics tribes came together to absolve each other of past grievances in the interests of uniting against the Otomarcan invaders. This newly formed alliance, known as the Iron Confederacy, would go on to successfully contain the Otomarcan armies behind the Oskandowa Mountains in a series of conflicts known as the Thunder Wars, and ensure peace between the republics for over a century. The end of endemic warfare in the region allowed for the emergence of the Mezhte creole group, the result of mixing between Umbiers and indigenous tribes.

By 1629, there were 6 Otomarcan colonies in Eastern Norumbia. The Umbier colonists did not share a language with the Otomarcan Crown and largely considered themselves as separate, autonomous entities from the metropole, maintaining strong traditions of local elections and self-governance, with most taxes going directly towards the infrastructure and defense of the colonies themselves. The colonies were major participants in the 1670s Battle of the Salacian, in which Otomarca was militarily and economically devastated. While its Norumbian colonies were not seized by Ghant, Otomarca's ability to govern them was severely reduced. Defense and taxation became a continental affair, further reinforcing the colonies' spirit of sovereignty. By the early 1700s, when Otomarca began reasserting its control over the region in an attempt to counteract Ghantish influence, the colonies bristled under royal control. In 1731, the colonies declared independence. The Continental War, or First Valzian Revolution, was short and decisive, and by 1733 the Treaty of Ghish forced the Otomarcans to recognize the independence of all of their Norumbian possessions.

Great Norumbia

Of the 6 newly independent colonies, the northern states of Nytīrsland and Mågdeland united under the Federal Republic of Valzia while the remainder went on to form the Republic of Rökkurlynd. Independence resulted in increased investment in and immigration to the region as various powers took an interest in harnessing the potential of the new situation to counteract their rivals. This reignited and fueled more endemic warfare between Valzia and indigenous polities as Valzian settlers once again pushed into the Oskandowas and Osawanons.

Expansion of Valzia and Rökkurlynd into historically indigenous lands caused upheaval throughout the Gishigami basin, reminiscent of the first wave of expansion in the 1600s. Large numbers of settlers encroached across the Oskandowas, supported by large numbers of foreign mercenaries intent on opening Wazhenaby markets to foreign powers. By the late 1700s, this marginalization led to the popularization of the political-religious movement called Chirawashiwin ("Thunder Dance"), a pan-indigenist milleniarianist belief system which called for all Norumbian tribes to unite and banish the Belisarians from the continent. A Bewenak-born Hazira chief and scholar, Asherion (Hazirat'e: Atejirehiga, "He-Who-Sets-the-Prairie-Grass-on-Fire-Suddenly-Like-Lightning", colloquially called "Firestarter"), was an ardent follower of the Thunder Dance who rallied nations to its cause and led them to victory against the Valzians, going on to conquer much of eastern Norumbia in a series of conflicts known as the Asherionic Wars, with the goal of creating pan-indigenous Norumbian federation known as Great Norumbia. Following the invasion of Serkonos in 1811, Asherion was opposed by coalition of states with the stated goal of containing Great Norumbia, with the Latin Empire (including its Belfrasian colonies), Gristol, Serkonos, and the Llahache and Anágan states of Tlåtåw, Ighai, and Dzillbesh pledging to liberate conquered territories and remove Asherion from power. Latium was immediately opposed by its historical rivals, Ghant and Sante Reze.

Asherionism called for a single, united federation of indigenous republics spanning the entirety of the Norumbian continent, firmly based in traditional usufructuary and direct democracy which could liberate all indigenous Norumbians. Private property was typically confiscated to community councils which were partially elected and partially overseen by appointed officials. Most forms of Christianity were discouraged or suppressed in favor of a decentralized school of charismatic Anabaptism. Despite repressive stances towards Belisarian culture, Asherionic policies notably gave women and the poor the right to vote and participate in politics for the first time in many of these communities, and also allowed homosexual and transgender individuals to identify openly. This led to a phenomena in which the traditionally oppressed portions of society were disproportionately politically active under the new regime, and frequently favored by Asherion and his officials.

As Great Norumbia expanded across the continent, it attempted to mediate and arbitrate for disagreements between indigenous nations it absorbed in an attempt to create a stable, functional republic in the frontline's wake. In many cases, these solutions were the result of Asherion's personal charisma or judgement. This created a series of client states whose loyalty depended on Asherion's personal guarantees or friendships; thus, as Asherion traveled farther away with his armies, these client republics would grow more fractious without close supervision of federal overseers. Following an arduous, mobile campaign in the scrublands of eastern Elatia, Asherion launched an invasion of Belfras in 1817 which quickly ground to a halt in the rainforests of Mondria and took heavy losses from disease and exposure. In 1822, Asherion himself was captured and imprisoned, freed by a Rezese raid, captured again, then, in a deal struck in the Treaty of Thessalonia, granted adoption into House Cardiki and accompanying property; he then proceeded to use his new resources to flee the country and once again attempt to rally Great Norumbia before being defeated at the Second Battle of Pontiac-Bernadotte. Exasperated, the coalition reached an agreement in 1824 in which Asherion would be given a military position in Aztapamatlan but effectively remain a prisoner in the hinterlands of Oxidentale.. Asherion spent the rest of his life in the service of the Heron Empire, commanding forces in Araucania and fighting in the Second Araucan War. Asherion died in his sleep in 1839 at the age of 68 in Amegatlan, Aztapamatlan, and his body was preserved in salt and returned to Wazheganon for burial.

Asherionic Federation

Following Asherion's death, Great Norumbia fractured into many independent polities, most too vast and disparate to be corralled by the post-war coalition. In the northeast, the modern states of Mniohuta, Rökkurlynd, and Wazheganon took shape. Officially established on July 8th, 1823, 21 years after the formal foundation of Great Norumbia, the Asherionic Federation of Wazheganon claimed to be the direct successor to Great Norumbia and espoused Asherionism as its fundamental ideology. Although Dowazhabymowin remained the lingua franca of government and trade, Wazhenaby leaders attempted to forge a new sense of civic nationalism and plurinationalism based on pan-indigenous ideals. As a federal communalist council republic, this represents the final structural evolution of the state of Wazheganon into the modern day, although significant territorial and political changes have occurred since.

Wazheganon's first several decades were marked by feuds and competition with neighboring republics, both over resources and old tribal disagreements that had been reignited without Great Norumbia's stabilizing pressure. The First Osawanon War, fought from 1827-1831, nearly saw the annexation of Bewenak from Rökkurlynd, but international hysteria about a resurgent Great Norumbia led the war to result in a stalemate and status quo ante bellum.

Around the 1860s, cooperation with Talaharan organizations sparked the beginning of industrialization in Wazheganon. Beginning in the coastal cities of Menahok and Viktorya, it quickly spread to the interior as the Gijizībi and Gishigamig facilitated an extensive shipping network that allowed vast quantities of goods and resources to be moved from the heart of the country out to sea in a relatively cost effective fashion. The Secretariat of Development was established in 1868 to assist local governments with the growing pains of urbanization and mechanization, building swaths of social housing, facilitating make-work and relocation programs, and planning new rail networks that eased the Secretariat of Distribution's coordinated plans to increase production and reduce labor nationwide. This coincided with the Second Osawanon War from 1863-1875, which saw protracted conflict in the southern Osawanons between Mniohuta and Gristol-Serkonos. Wazheganon, supporting Mniohuta, completed a railway from Chugara to Chunkaske (the "Chu Line") in 1870, which supplied the frontlines with ammunition and foodstuffs. This entire era of industrialization, from the 1860s-1900s, was labeled "the Ursine Transformation" (Makwa Ånzinågo'idizo), following a speech of statesman Wågimitigøg Namebin, who compared to process of reforming the economy around industrial technology to that of a mother bear preparing for winter and protecting her cubs.

Long-term planning for industrialization, urbanization, and their effects on culture, health, and economics soon began to tint the institutional culture of the federal government, orienting it towards a technocratic mindset. In 1873, the traditional Dowazhaby calendar was replaced with a standardized version made to keep time with the Gregorian calendar and facilitate industrial planning, causing outcry from conservatives and clergy, and in 1881 the . Awasin, whose forerunner had joined the Iron Confederacy in 1636, seceded from Wazheganon in 1885 due to dissatisfaction with the rapid changes in lifestyle and culture that accompanied Wazheganon's industrialization campaigns. The Third Osawanon War, from 1893-1895, saw Wazhenaby and Moxish troops briefly invade Chenes to prevent it from federating into Gristol-Serkonos, vindicating the success of the decades-long economic project by victory against what had previously been seen as a much larger, more developed threat.

Springtime Reforms to present

The first decade of the 20th century was characterized by upheaval in the Catholic Umbier population, which led to the gradual loosening of restrictions on and a campaign to destigmatize the Catholic Church, which was no longer seen as a significant threat to democracy in Wazheganon. In 1909, Bemångik Nahanåhkosiw Namapen's administration announced and began implementing a series of policies, which would come to be called the Springtime Reforms, that would protect minority groups against discrimination, implement more oversight for the federal government, and scrutinize the power of large state-owned enterprises.

The Fourth Oswanon War, from 1921-1924, was a renewal of Wazheganon's internationalism and support for revolution abroad. Triggered by the 1921 Bewenak Revolution, the war saw the annexation of Bewenak into Wazheganon and scattered socialist and indigenous uprisings throughout the Osawanon countries.

In 1927, a series of conflicts began between Wazheganon and Ghant over fishing rights in the Sea of Dakmoor, called the Cod War. These disputes remained relatively minor until 1936, when Wazheganon entered the Great Otomarcan War on the side of the North, bringing it into a formal state of war against Ghant. As Ghant dissolved into civil war (the Mad Emperor's War), Wazheganon launched an ambitious amphibious invasion of Dakmoor in support of a rising Leftist movement in the country. While the Leftists ultimately failed to abolish the monarchy or implement economic democracy, Wazheganon's assistance to the victorious party of the civil war led to an amicable resolution of the original fishing disputes in 1943.

In 1975, Ashahiga Sekåk Awahsah used escalating border skirmishes in Bewenak to assume emergency powers and perform a coup of the civilian government. Awahsah, who harbored invictosocialist]] sympathies, also began clamping down on Christians and other minority communities. This all provoked mass uprisings by both civilians and paramilitary militias. The military’s loyalty was divided; this, combined with mass uprisings and protests by civilians and militias, ensured that by May 1976 the putsch, which had evolved into a quasi-civil war, was defeated. Awahsah committed suicide after writing a manifesto incriminating many members of the military and intelligence community. Thereafter labeled the Emergency, the attempted coup was a redefining moment for modern Wazhenaby politics. It cemented the necessity of anti-authoritarian, anti-racist, and restorative measures throughout Wazhenaby institutions.

The Fifth Osawanon War was fought from 1993-1997 and resulted in the loss of the Bewenak to Rökkurlynd, almost 15% of Wazheganon’s territory. This war severely fractured diplomatic relations in northeast Norumbia, and it continues in the form of a guerrilla war in Bewenak to this day.

In December 2019, the Wazhenaby military was deployed to intervene on the behalf of the Democratic Coalition in the Enyaman Civil War, a highly divisive action which eventually lead to a stalemate in the civil war and the creation of the Enyaman Council State.

Government and politics

Wazheganon is a federal, libertarian socialist council republic in the communalist tradition. Although it lacks a codified constitution, democratic norms are strong in Wazhenaby politics, with human dignity, social consciousness, and individual autonomy enshrined in customs and precedent. Each constituency at every level is considered theoretically and nominally independent and sovereign; this means that, so long as the core concepts of the Wazhenaby system (namely consensus, free association, and militant democracy) are not violated, there is a wide variety of political and economic organization possible within Wazheganon, ranging from traditional indigenous hereditary councils to syndicalist workplace-conglomerates.

Federal legislative powers are vested in the Federate Congress, a bicameral body under a delegate model of representation. In the 19th century, some political scientists regarded the Federate Congress as a sexacameral body, but today it is widely considered bicameral despite minimal changes to its structure. The lower house, the House of Nations, consists of 500 members (each representing approximately 100,000 constituents each) who are elected proportionally at the commune level. The House of Nations elects a Bemångik (sometimes translated as "General Secretary"), who serves a role similar to the prime minister of other countries, forming the cabinet, presiding over meetings of the legislature, and holding most day-to-day executive responsibilities. The Landscouncils (akizagaswyidiwin) are four bodies which have variously been regarded as their own legislative houses or special committees. They include: the Sky Council, which consists of religious leaders from virtually every major Wazhenaby religious group, who are consulted for moral and spiritual advice but lack any tangible political power; the Garden Council, which is made up of female representatives of the House of Nations and various appointed experts, and can be consulted on and intervene in matters they feel affect women or the family, as well as acts related to war; the Forest Council, comprised of traditional land stewards and appointed environmental scientists, who advise on and can intervene on policy related to the environment and agriculture; and the River Council, which is a technocratic committee tasked with determining the long-term impacts of government policy and actions, "for up to seven generations".

The upper house of the Federate Congress is the Grand Council, consisting of 19 members. In addition to the Bemångik, speakers of each of the four Landscouncils, a representative from each of ten republic councils, and one member of the House of Nations under the age of 40, the Grand Council appoints the Baswenåzhi (sometimes translated as "Chancellor"), who serves as a head of state, is a member of the Grand Council, and is in charge of foreign affairs.

In addition to the civilian government, there is a democratic military government which has historically functioned in parallel, electing an Ashahiga (sometimes translated as "Marshal") who serves as the commander-in-chief and final executive on defense policy, as well as being able to assume emergency powers in times or war or crisis. The ashahiga serves on the Grand Council as well. Together, the baswenåzhi, bemångik, and ashahiga form the Thunderbird Council, the triumvirate executive of the country.

Political parties in Wazheganon function as caucuses similar to the Rubric Coast salon model, called måwnji'diwineg or conferences. A conference is, broadly defined, simply an organization of like-minded people, with structures ranging from a codifying common platform to arranging for political debates and fundraisers. They are fluid entities, with most politically active citizens likely to be a member of several simultaneously, and primarily serve as venues of political debate and experimentation. This makes a conventional visualization of congress as divided by party or coalition largely useless in a Wazhenaby context.

Wazheganon's federal system has historically drifted between varying levels of centralization and control. Federal control reached its height in the late 1800s and the 1970s. Some consider Wazheganon a de facto confederation due to its bottom-up formation and the legal autonomy of its various subdivisions, while others consider the overarching federal government, which enforces certain standards and obligations for all members, to soundly disqualify it from this category. The country has self-styled as a federal entity since its inception, and the federal-confederal debate is one of the most prominent, regular political issues throughout all of Wazhenaby political history.

The Autumn Lodge in Mawosåw is the office and part-time residence of the Grand Council, as well as the bemångik and their cabinet.

The Federation Building is the meeting place of the Federate Congress.

Gåjībayåbøzh is the headquarters of the Zåskoniwag.

Law

Wazheganon has a common law system originating from a fusion of Asherionic law, Otomarcan law, and socialist law. The word "court" in a Wazhenaby context is sometimes translated as "council" or "tribunal". At the local level, citizens of a måwnzoneg elect members of a neighbors' court, which serves to mediate minor disputes and make decisions on minor criminal cases. At the sagimawin level, citizens (who need not be trained jurists) are elected to six-member regional courts, mediated and presided over by a trained jurist appointed by the sagimawin legislature. Regional courts lead into the national courts, comprised of a triumvirate of trained jurists appointed by the national legislature. The specifics of term lengths, term limits, compensation, and titles vary considerably depending on the jurisdiction. At the federal level, the Federate Peacemaking Court serves as the court of last resort for the entire country, and is presided over by seven judges appointed by Congress for single 20 year terms.

Wazheganon lacks the conventional police departments found in other countries. Instead, law enforcement is handled primarily by local miwenokig (sing. miwenoky, derived from the official phrase bami'iwewininiw anokītåge, roughly translating as "caregiver service"), whose personnel are colloquially called bamiwineg (sg. bamiwin), usually headed by a reeve's office, with national-and-federal-level agencies providing broader supporting services. "Miwenoky" is a term for an umbrella organization containing multiuple specialized and interconnected agencies for public safety, staffed by both professional specialists and volunteers. These can include first responder teams trained for medical and mental health emergencies, fire departments, criminal investigation specialists, dedicated traffic enforcers, sexual assault response teams, rangers who monitor and maintain parklands, domestic violence response specialists, substance abuse or homelessness assistance offices, armed rapid response units, and so on.

Traditional beat cops are replaced with kawåbinig (translated as "watchmen", sometimes as "carabinier"): uniformed, unarmed civilians trained in conflict de-escalation, whose primary responsibility is to identify problems and emergencies on the ground and coordinate a swift, suitable response from other agencies. Kawåbini often employ intimate community policing strategies and neighborhood police boxes are common, augmented by ubiquitous neighborhood watch organizations who are sometimes given training in mediation by Miwenokeg.

The Wazhenaby justice system is oriented towards restorative justice. Capital punishment has been a cultural taboo for centuries and was finally formally banned in 1811, and homelessness, possession and recreational use of drugs, and sex work are all decriminalized. Courts are oriented around mediating crimes and examining and taking steps to address their causes on both an individual and systemic level through extensive social services, community outreach, and educational programs. In cases where punishment is deemed helpful, proportional fines, probation, and community service are typically employed. Incarceration is only contemplated in cases considered unrelated to mental illness and more severe than a misdemeanor, and even then house arrest is generally the favored method of incarceration. There were 33 incarcerated individuals per 100,000 people in 2020, and the recidivism rate in 2016 was 19%, very low in an international context. Penitentiaries where individuals are incarcerated are managed at both the republic and federal levels. These facilities generally resemble university campuses or boarding schools, with prisoners allowed considerable freedom of movement and activity within a given campus where they live in dormitories, and are able to make use a various facilities or even make daily excursions into the surrounding community. Many penitentiaries may also be democratically-managed by staff and prisoners, and make use of extensive, paid prison labor to clean and maintain their facilities. Depending on their specific sentence, prisoners may be required to attend or participate in certain therapeutic, psychiatric, or educational programs; typically, various elective programs and courses are also available, which may go towards acquiring technical, vocational, or other post-secondary degrees or certifications. The most extreme punishment in the Wazhenaby justice system, for those who are eventually deemed "exhaustively unrehabilitatable", is a prolonged or even life sentence in penitentiaries called reflection camps. Reflection camps are rural estates where prisoners are confined and directed to live communal, self-sufficient lives chopping firewood, farming and cooking, and studying in on-site libraries, with therapeutic and educational resources available on request and regular reviews to determine whether they can return to a conventional penitentiary or qualify for parole or compassionate release. Reflection camps have been criticized by reformers and international observers as unusually cruel for their isolating nature and the sometimes unpleasant, dangerous nature of wilderness lifestyles.

Foreign relations

Wazhenaby foreign policy has been primarily characterized by internationalism and permanent agitation, in which it simultaneously seeks close military-economic cooperation with other socialist states while actively agitating for continuous democratic and socialist reform even in allied states, with the goal of encouraging a continuous dialectic which encourages reform and revolution in non-socialist states and prevents extant socialist states from metastasizing into authoritarian hierarchies. This is done not only through conventional subversive means such as propaganda, funding, assassinations, or arming sympathetic militants, but also through constructive measures among foreign populations, such as the building of infrastructure, training of teachers and doctors, and assistance in developing robust mutual aid networks. The foreign policy of the Wazhenaby establishment has been variously described as functionalist, constructivist, and neo-Gramscian in nature.

Wazheganon is a founding member of the Kiso Pact and a major advocate for both the expansion of the organization and deepening of military-economic ties between its members. It is also a member of the Forum of Nations, Joint Space Agency, Kiso Pact, Global Observatory of Labor (through the Western Economics Institute), and Common Congress of Oxidentale and Norumbia. It was a founding member of the Osawanon Community, but has boycotted it without renouncing its membership since the 1993-1997 Fifth Osawanon War. It has supported Leftist, anti-monarchist, and indigenist political parties, social movements, and insurgents in Rökkurlynd, Enyama, Gristol-Serkonos, Awasin, Mutul, Hvalheim, and Kayahallpa. In December 2019, Wazheganon formally entered the Enyaman Civil War in support of the Democratic Coalition, and in June 2022 was among the first to officially recognized East Enyama.

The core of Wazheganon's foreign policy is found in deep military, economic, and diplomatic ties across the Salacian Ocean, participating since the 1960s in the Northern Common Development Agreement with North Ottonia, Ostrozava, Talahara, and Tyreseia, all fellow Kiso Pact members in modern times. Historical and military ties to Tsurushima also shape Wazhenaby concerns. Wazheganon was one of the founding members of the Global Observatory of Labor, in partnership with Pulau Keramat. Also notable is Wazheganon's pursuit of cooperation with ordosocialist states such as Elatia and Jhengtsang despite ideological disagreements. Elements within Wazhenaby diplomatic circles informally claim the country played a decisive role in the gradual democratization of Elatia leading to the landmark 2021 constitution and elections there.

There is a long, friendly history with Sante Reze, with whom Wazheganon shares traditions of environmentalism and free association. Ghant has been situationally regarded as an unusually genial monarchist state. Mutul, through Elatia and anti-Belisarian politics, could also be considered a distant strategic ally. Before the Fifth Osawanon War, the country shared cool but amiable relationships with Gristol-Serkonos, which have since greatly deteriorated. Wazheganon is close allies with Awasin and Mniohuta for historical, cultural, and economic reasons. All are party to the Norumbian People's Alliance with Wazheganon, creating a customs union, basic common market, and open border between the three countries, who also share a mutual defense pact.

Military

The federal armed forces of Wazheganon are called the Zåskoniwag ("Ones Who Give A War Cry", ZKW). It is a professional, volunteer force of approximately 200,000 active personnel and 400,000 reserve personnel. It is comprised of four branches: the Mīkanoseg (Army, lit. "(War)path-Walkers", MKS), the Bizhiwånigowag (Navy, lit. "Panther-Riders", BZW), the Agonjiniwag (Air Force, lit "Ones Who Soar In The Sky", AJI), and the Bekådiziniwag (Reserves, lit. "Patient Ones", BZI). The Zåskoniwag is a democratic organization, with commanders elected at all levels and semi-regular assemblies of military units guiding internal policy and organization. The Ashahiga serves as the commander-in-chief and final executive on matters of national defense; during times of crisis, the Ashahiga can assume emergency powers that allow them to direct the civilian government. This system descends from the historical Dowazhaby tradition of having a war chief who would serve as a temporary authority during times of conflict. Advising the Ashahiga is the General Command, consisting of high-level elected commanders and technical specialists, trained officers, diplomatic staff, and other experts.

The Gishibåkwånan (lit. "shield, mantlet", GBK) represent Wazheganon's paramilitary and militia forces, in which locally organized militias are subsidized, trained, and overseen by Congress so that they may be called up for territorial defense, disaster relief, and other functions. However, the Gishibåkwånan is a distinct organization from the Zåskoniwag, and in some political currents it is even suggested as a counterweight to power-grabs by the professional military.

Wazheganon's military expenditure was $49 billion in 2020, approximately 3.5% of national GDP and 7% of the federal budget. Wazhenaby equipment is typically purchased or licensed from allies, such as the PAL-WZ, a variant of the Ostrozavan PAL rifle, which was the standard issue rifle of the Zåskoniwag from 1961-1993, and the M5 Bizhiw which is an improved variant of the Ostrozavan OPU-S65/G2 in use since 1982. However, some indigenous development has taken place, most notably the BN-93, which became the standard service rifle in 1993, and the Wenon G10 Cojge, a multirole fighter-bomber that entered service in 1997. Wazheganon is party to several international arms development and sharing treaties, most notably the Northern Common Development Agreement. While it is not considered a major arms exporter, Wazheganon has contributed several designs for missiles, aircraft, and precision rifles to its military allies.

The Wazhenaby intelligence community is generally recognized to play a major role in strategic military and foreign policy decisions, historically being decisive tools for political agitation, proxy warfare, and military and economic intelligence. The Federal Intelligence Group (ånzwīdøkodådijiggikendåsowin, AWG, stylized as AUGUR) is the primary intelligence gathering apparatus, encompassing numerous disciplines such as signals intelligence, measurement and signature intelligence, and geospatial intellignece. The Center for Permanent Revolution (Idiwigamigåbigizhibåbide; WAG, stylized as WAGER) is the primary espionage and human intelligence organization, and also participates in distributing economic aid and propaganda, as well as, allegedly, the arming and training of insurgents and destabilization of governments in other countries. The main counter-intelligence and counter-terrorism body is the Institue for Internal Review (Gikendåsøwigamigwīyawgikenjigewinan, GWG, stylized as GAVEL).

Constituencies

Wazheganon is a federal polity consisting of 10 constituent federate republics (dibishkødam) and 2 common territories (mådaøzhaki). These republics are generally formed along ethno-linguistic lines, but are organized from the bottom up in the manner of a council republic, comprised of 500 sagimawinig (intended to represent approximately 100,000 inhabitants each), which are in turn made up of 1,152 måwnzoneg, and so on, all governed by executive councils elected by the next lowest administrative units. The smallest functional subdivisions are the wījige, which typically represents around 200-2000 people; all other, smaller units (such as the dawån) are simply organizational tools for local agencies. Each individual administrative unit across all levels is, at least nominally, sovereign, and has the power to act or reorganize as it deems fit depending on the consent of the smaller units.

| Commonwealth | Capital | Population | Area (km2) | Density (per km2) | GDP (U$D) |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mawosåw | 47,703,216 | 1,854,816 | 25.72 | $1,327,580,501,280 | |

| Glywa | 1,908,129 | 47,840 | 39.89 | $39,827,415,038 | |

| Dodagon | 7,632,515 | 62,944 | 121.26 | $212,412,880,205 | |

| Mishkodaga | 8,109,547 | 475,296 | 17.06 | $199,137,075,192 | |

| Salela | 95,406 | 33,824 | 2.82 | $2,655,161,003 | |

| Amested | 3,339,225 | 19,232 | 173.63 | $92,930,635,090 | |

| Chugara | 4,293,289 | 154,112 | 27.86 | $92,930,635,090 | |

| Åkonemy | 9,540,643 | 137,568 | 69.35 | $292,067,710,282 | |

| Viktorya | 3,849,650 | 23,648 | 162.79 | $132,758,050,128 | |

| Sosasø | 2,385,161 | 484,128 | 4.93 | $39,827,415,038 | |

| Menahok | 5,724,386 | 38,624 | 148.21 | $185,861,270,179 | |

| Gåmoshowa | 14,311 | 374,528 | 0.04 | $398,274,150 | |

| Mawosåw | 810,955 | 3,072 | 263.98 | $36,773,979,885 |

Economy

Wazheganon is an industrialized country with a high standard of living, a low GINI coefficient, and a GDP per capita of $27,830. The service sector contributes approximately 60% of the total GDP, manufacturing 35%, and agriculture 5%. The unemployment rate was 4.8% as of January 2020. Major Wazhenaby exports include capital goods, commercial/utility vehicles, wood and paper products, industrial machinery and components, and processed foodstuffs (especially dairy and corn products). Aeronautic, civic, and architectural engineering are some niche fields Wazhenaby firms are internationally known for. Wazheganon possesses a wide range of natural resources, including lumber, iron, copper, nickel, palladium, iridium, and gold. It is also a minor exporter of hydrocarbons and uranium in the western hemisphere. Wazheganon is party to the Norumbian People's Alliance with Awasin and Mniohuta, which facilitates a customs union, basic common market, and open borders between the three countries.

The Wazhenaby economy is a socialist system consisting of a series of interdependent economic models, and all land is held in usufruct. Generally speaking, all jurisdictions function under a socialist mode of production in which all firms are democratically owned and controlled through workers' councils, although socialism is technically not enforced by law. Due to this structure, the Wazhenaby economy largely lacks stock exchanges or real estate markets, and its financial industry is oriented almost entirely around cooperative banks.

At the local level, most citizens' basic needs are addressed by an informal gift economy drawn from local farms and businesses, with many specialized services also provided in a system of mutual aid. Basic needs such as food and housing have been thoroughly decommodified and are provided for by various entities. ødenag and måwnzoneg frequently collaborate together in the spirit of mutual aid, sharing resources and expertise to accomplish both shared and individual goals. Måwnzoneg, sagimawineg, and republics also participate in a decentralized planned economy in which organizations at various levels negotiate and arrange for the sharing of resources, manpower, and expertise in pursuit of meeting needs and planning goals. If the local economy is unable to provide an important good, for example, food in an urban area, economic-political entities are tasked with setting up supply lines for it. The federal government helps facilitate this planning through the Federate Economic Coordination Council (Ondazaga) ), which aggregates and analyzes economic data and stimulates communication between smaller economic entities. Ondazaga is under the purview of the Secretariat of Distribution, which directly participates in dirigisme to direct and foster economic activity, and uses government agencies and state-owned enterprises, known as commonwealth corporations, to manage and deliver goods and services to areas that other layers of the economy have difficulty providing for.

Wazheganon's currency is the asha, abbreviated by the symbol ᔕ or W₳, which is issued by the Federate Bank of Wazheganon; 1 asha is divided into 100 mīdeseg, or m. The asha is pegged to the price of silver. Given the country's economic structure, currency is less preferable in most transactions than institutional planned bartering or reciprocity; as such, currency is typically only used in either high-level resource transfers or for the purchase of certain luxury goods for personal use, such as alcohol, electronics, or artwork, or else to make up for supply chain disruptions or systemic inefficiencies by buying goods usually acquired in other ways from international businesses and commonwealth corporations. It is entirely possible, albeit unlikely, for an individual to go their entire life without interacting with currency.

Most conventional Wazhenaby firms (that is, ones which aim to turn a profit and expand, or do business internationally), are typically cooperative federations or worker-consumer hybrid cooperatives. These firms are generally required to meet requirements for ethical trade and sustainable economics in their supply chains, as well as meeting a certain standard of unionization or employee-ownership, in every country they do operate in, and foreign businesses are held to similar standards if they wish to operate in Wazheganon. As a result, most foreign firms operating in Wazheganon tend to be already-existing cooperatives or state-owned enterprises, especially those originating from other socialist countries. A few internationally well-known Wazhenaby businesses include the fast food chain Janner's, construction-equipment manufacturer Onwala, and furniture retailer Kezøngy. Some countries refuse to allow Wazhenaby firms to do business in their territory on the grounds of preventing a trade deficit, or avoiding Leftist subversion from active examples of economic democracy in action. The vast majority of Wazhenaby businesses have fewer than 250 employees.

Agriculture

Agriculture and animal husbandry make up as much as 5-12% of the Wazhenaby economy, unusually high for an economy otherwise firmly based in the manufacturing and service sectors. This is because Wazhenaby attitudes towards environmental stewardship and decentralized economics cause broad, labor-intensive, and sustainable agricultural projects to be nearly omnipresent around most populated areas, sometimes seasonally or situationally involving large swaths of the community which would not usually be employed in the agricultural sector. Agriculture is treated as a complex process requiring extensive, specialized expertise in science, economics, and indigenous knowledge. Agroforestry, silvopasture, polyculture, permaculture, aquaculture, and mixed farming are all employed in ways that are often idiosyncratic to a specific region, continuously tweaked according to changing conditions, with operations typically remaining relatively small and only rarely resembling the immense monocrop farms of some countries. Approximately 12% of land is used for agricultural or livestock purposes.

Wazheganon is the world's largest producer of manoomin, which is grown in paddies and lakes throughout the country, often as part of a polyculture incorporating bluegills, muskellunges, and even ducks. Fluvial and oceanic fisheries are common, with lobsters, carp, and cod being the principle catches; fishing is quite regulated, in order to maintain stable, healthy populations. Wazheganon is also one of the world's largest producer's of maple syrup and derived confections. Maize is the most cultivated crop in the country, with green beans, potatoes, squash, and cabbage also being prominent. Corn whiskey, such as Matagamon razmus, is the most popular and famous Wazhenaby alcohol. The moderating effects and good soils along the Gishigameg allow fruits such as apples, cherries, plumbs, pears, peaches, and even grapes to be readily grown along the lakeshore. Orchards are often augmented with strip cropping and silvopasture to manage pests and shelter livestock. Blueberries, cranberries, strawberries, and walnuts are also common.

Dairy and beef are by far the most important livestock products, and the country is one of the largest dairy exporters in the world. Milk, cheese, butter, and derived products, are all major components of national cuisine and some of the most internationally recognized foods from Wazheganon. Cattle ranching and dairy farming are found throughout the country, but are particularly common in the southwest. Factory farming is generally illegal. There were approximately 11,000,000 cattle in Wazheganon in 2017.

Madimoseg (sg: madimos; from Wåyachawywin, madi-moscosis, "ugly calf") are a cattle-muskox hybrid first produced in the 1860s, which today are the ubiquitous Wazhenaby livestock. Their hardy build, long coats, and foraging skills make them well-suited for silvopasture in the cold, snowy, windy winters of Wazheganon. Their beef is considered unusually tender and low in cholesterol, while their milk has a high butterfat content. Their downy undercoat provides wool, called wepīwy, which is praised for its softness and insulation and used for textiles.

Energy

Nearly all electricity in Wazheganon is provided by nationally-owned Federate Electric (which is publicly branded as Wåsigan). Other minor energy providers exist in some republics, such as Boures Energy Cooperative which provides 20% of Nytīrsland's energy, but Federate Electric maintains a monopoly on the Wazhenaby energy sector. In 2018, the entire country consumed approximately 468,064 GWh, or 9,812 KWh per person. Roughly 60% of energy is generated by hydroelectric power, 20% by wind power, and 10% by nuclear power, with the remaining 10% coming from assorted sources, including natural gas, solar power, marine power, and biomass. This is supplied by 4 nuclear plants, 63 hydroelectric plants, over 10,000 wind turbines, and numerous other stations. The majority of energy produced by fossil fuels comes from generators powered by liquefied petroleum gas and diesel, used in extremely rural areas. Following the narrowly avoided meltdown of Kumazawa Nuclear Power Plant in 2020 as a result of damage caused by the Enyaman Civil War, Federal Electric began considering phasing out its nuclear plants in favor of wind and marine energy.

Wazheganon possesses relatively sizable reserves of natural gas, particularly in the northwest and offshore on the northeast coast. Awasi, Zacapine, and Ghantish firms have variously been contracted to augment domestic drilling infrastructure. However, domestic drilling is heavily regulated due to environmental concerns, meaning that the vast majority of hydrocarbons are imported, with Awasin and Elatia being major suppliers. Uranium is also mined in western Kodywakī and Oskåtosa; this uranium has become more commercially viable since the beginning of the Enyaman Civil War, which has disrupted one of the largest uranium industries in the world. Federal Electric has been involved in various foreign projects to develop energy infrastructure and extraction industries in other countries.

Tourism

Tourism is a major pillar of the Wazhenaby economy, with the country welcoming approximately 11 million international tourists annually and an estimated 1.6 million Wazhenabyg being employed in the industry. The Secretariat of Culture helps to advertise and develop the industry under the commercial name "Haho, Wazheganon!".

Nature recreation is one of the most prominent tourist activities, with Wazheganon's many forests, rivers, lakes, and mountains providing ample space to hike, boat, fish, hunt, ski, and camp. Wiglatemak National Park, on the Weskoki-Meskosin border, is the most popular national park by number of visitors, with 8.7 million in 2020, and Dolidak National Park and Preserve in Oskåtosa is the largest, at 36,128 km2. Mistasin International Park and Preserve in southern Oskåtosa is unique in that it spans the borders of Wazheganon, Awasin, and Mniohuta, measuring a total 60,992 km2, 21,248 km2 of which are in Wazheganon.

Nytīrsand and Meskosin are roughly tied as the most popular republics for international travelers. Both represent distinct ecological and cultural regions. There are many well-preserved, historic Old Towns, even in relatively small cities, cataloging the diverse history and development of various regions. Handicrafts such as beadwork, wood carvings, and pottery are popular, novel souvenirs for foreigners. Some of the most famous and popular tourist attractions in Wazheganon include: the Mošógračąk archaeological site near Chugara, featuring preserved and reconstructed earthworks, monuments, and buildings from around 900CE; Jankarayonwå, large waterfalls where Lake Adaluka flows into the Gijizībi; the Jabwygan Museum of the Twenty-Three Nations, a historical and art museum celebrating the cultures of Wazheganon's many ethnic groups; and the Commonwealth Commons in Mawosåw, a collection of government buildings, museums, parks, and cultural centers in the federal capital.

Outgoing tourism tends to go to either neighboring Norumbian countries or other social countries; namely, Mniohuta and Otomarca are the two major destinations for Wazhenaby tourists. Given the unconventional economic practices in Wazheganon, many Wazhenabyg opt for pre-arranged guided tour packages outside of familiar Awasin or Mniohuta, which minimize the chances of misunderstandings or accidents.

Transporation

Wazheganon has over a million kilometers of paved roads, 16,384 kilometers of expressways, and 24,867 kilometers of railway, all of which is nationalized. Transportation infrastructure is overseen by the Secretariat of Infrastructure. Affordable and convenient public transportation has been regarded a cornerstone of public policy since the early 1900s, with the federal and republic governments investing in extensive transit and rail networks. Most Wazhenaby cities are built with walkability and bike-riding in mind, but public transit is common in most larger cities, particularly in the form of light rail, although buses have also experienced a boom since the advent of electric buses in the 1990s. Public transport is usually zero-fare.

High-speed rail runs between most major cities. The Gerøgera Mountains present a challenge for the national high-speed rail network. Måkikåm, one of the most remote major cities, is connected to the rest of high-speed rail network only by a line connecting south to Sosasø, which then connects to east via the Sepola Valley north of Lake Masisik. Regardless, if one were to drive through the mountains from Måkikåm to Wiswåmuk, roughly 600 kilometers to the northeast, it would take roughly the same amount of time as this inefficient high-speed rail route, about 8 hours total, despite the latter being over four times longer in distance. A continuous, coast-to-coast high-speed rail ride from Sosasø to Viktorya takes approximately 6 hours; driving roughly the same route would take about 4 days, assuming one drives for 8 hours per day, while a nonstop domestic flight from Sosasø to Viktorya takes 2 hours. Slower, lighter rail lines link many smaller cities into the national network and form what has been labeled a "rural sprawl" united by transit.

The largest, busiest airport in the country is Viktorya International Airport, with 16.8 million passengers in 2014. There are 241 airports, aerodromes, and heliports throughout Wazheganon. Gīwedin is the flag carrier and largest airline, although several other airlines provide international service. Air travel is very common in the far north, where roads may be unreliable or even nonexistent. The city of Jīgewe, on the northern coast of Kodywakī, is the largest city in Wazheganon that is inaccessible by road or rail, with 9,833 people; all travel in and out of the town is conducted via bush flying. Much of the country's north remains inaccessible by road or rail. The northernmost rail line is the Great Winivere Line going from Måkikåm to Awåsachaw, accompanied by a highway, but this is an outlier. The other northernmost controlled-access highway is the S29 running from Minokwa to Wiswåmuk.

Shipping on the Gishigameg is extremely important to the Wazhenaby economy. Specialized seasonal freighters known as lakers carry cargo throughout the lakes, and from the western part of the country up the Gijizībi, where it is transferred to larger, ocean-going vessels at ports like Dodagon, Weljemaj, and Wikemog. The port of Mishkodaga, which straddles the Båwitigong River alongside the Northern Locks, connecting the lakes Ginøgama and Gishigami, is the 9th busiest port in the country by sheer tonnage, and 4th by foreign exports. The busiest port in the country is Viktorya on the east coast. Travel and shipping by riverboat is also somewhat common during summer in many parts of the country, as extensive river and canal systems provide a viable alternative for passengers and cargo. The Mamøka Bridge is the largest in Wazheganon, stretching 10 kilometers (in six individual spans) across the Gijizībi where it flows from Gishigami, northeast of Jabwygan; the Mamøka Bridge is one of the largest suspension bridges in the world, with its longest span being 1,989 meters.

Science and technology

Indigenous Wazhenaby societies have had a tradition of learning and innovation since the late 11th century, independently inventing the water wheel and constructing advanced urban infrastructure including sewage systems, irrigation networks, and canals, as well as developing their own writing system by the 1200s. Indigenous knowledge has long served as the basis of complex agriculture, medical advancements, and environmental engineering. The Managadwam of Mawosåw, founded in 1641 in Mawosåw, is the oldest still-functioning university in Wazheganon and is also its foremost research university. Scholars from Mawosåw developed the educational philosophy known as the Meskosin Idea in the late 1800s, which calls for public research and education to serve towards advising public policy and solving technical problems so as to provide the greatest good to the greatest amount of people. Wazhenaby inventions and innovations include typewriters, gas-powered tractors, anticoagulants, bone marrow transplants, the flying shuttle, phosphate fertilizers, and pasteurization.

In 2020, research and development spending made up approximately 3% of the Wazhenaby economy, or $37 billion. The Secretariat of Knowledge maintains numerous research agencies, business incubators, and state-owned enterprises dedicated to scientific and technological research and development. The Wazhenaby Federal Research Center (WWNW) is the largest such organization. Chipek, a state-owned information technology firm, is responsible for maintaining the Wazhenaby section of the fediverse and developing free and open-source software for public use. Wazheganon also has a robust aerospace industry, with state-owned enterprise Wenon being the country's largest airline manufacturer and an international developer of communications systems, missiles, helicopters, and related systems.

Demographics

With a population of 47,703,216, Wazheganon is the second most populous country in the Osawanon Community, behind Gristol-Serkonos, and the fourth most populous country in Norumbia.

Its population density of 25.71 per km2 is deceiving, with just under half of the population living in just just 10% of the total land area, concentrated in the southeast quarter of the country. Oskåtosa is the least densely populated republic, with just 4.93 inhabitants per km2, while Mågdeland is the most densely populated, with 173.63 inhabitants per km2. This excludes the two common territories, each of which would respectively be the most and least densely populated subdivisions. The largest city is Jabwygan, with a metropolitan population of 1,437,310. 83% of the population lives in urban areas. Wazhenaby settlement patterns are characterized by large primate cities, which are the economic and cultural centers of a republic and several times more populous than any other city in the same constituency, with a mosaic of permacultures and natural areas spreading out from it. Even relatively small towns tend to be quite dense, with vast swaths of land left to managed wilderness and polyculture. The majority of Wazhenabyg, 63%, in 2020 reported living in family households, of which 77% were described as either multigenerational or extended families. A further 21% reported living with unrelated persons, and 16% reported living alone.

Wazheganon has a high immigration rate, driven mostly by economic policy and refugee resettlement. It is historically an immigrant country, with large portions of the population descended from immigrants from throughout Belisaria, Ochran, and Oxidentale. The immigrant population (defined as being born abroad or born in Wazheganon with foreign-born parents) is estimated to have grown by nearly a million people between 2010 and 2020, a large portion of which is believed to be refugees fleeing the Enyaman Civil War.

Wazheganon's fertility rate is unusually high for developed economies, at 2.2 children per woman in 2020, but its average age is nonetheless also high at 42.5 years. The average life expectancy is 81 years.

| Rank | Republic | Pop. | Rank | Republic | Pop. | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Jabwygan Viktorya |

1 | Jabwygan | Meskosin | 1,536,170 | 11 | Bochiket | Meskosin | 519,376 |  Dodagon  Mawøsaw |

| 2 | Viktorya | Nytīrsland | 1,397,866 | 12 | Askala | Jenasha | 485,747 | ||

| 3 | Dodagon | Jenasha | 946,921 | 13 | Tososa | Meskosin | 443,305 | ||

| 4 | Mawøsaw | Zhångweshaki, M.A. | 754,727 | 14 | Mishkodaga | Kodywakī | 427,133 | ||

| 5 | Menahok | Weskoki | 729,401 | 15 | Chugara | Madychīra | 329,350 | ||

| 6 | Amested | Mågdeland | 700,298 | 16 | Åkonemy | Meskosin | 393,463 | ||

| 7 | Sakyo | Jenasha | 677,711 | 17 | Weljemaj | Jajīgagī | 316,446 | ||

| 8 | Bajiwan | Kodywakī | 660,247 | 18 | Menysha | Kodywakī | 254,389 | ||

| 9 | Nykambrik | Nytīrsland | 621,001 | 19 | Glywa | Jajīgagī | 217,137 | ||

| 10 | Shahona | Weskoki | 568,113 | 20 | Sosasø | Oskåtosa | 173,452 | ||

Ethnic groups

Wazheganon is a plurinational country, the result of a long history of colonialism, immigration, and intermarriage. It is sometimes referred to as the "United Nations"; a common poetic name for the country is "the Twenty-Three United Nations", attributed to those nations which were party to the 17th century Great Peace of Mawosåw. Although there are no official statistics on ethnicity, self-reported statistics are available from private or academic institutions.

Historically, most of the Kadowakan-language speaking ethnic groups have identified as a single large meta-ethnicity, to varying degrees, called Nebesowyg (sg: Nebesowy) or Nawendeg (sg: Nawendy). This group made up approximately 60% of the population of Wazheganon in 2020. The two primary non-Kadowakan indigenous groups in Wazheganon, the Hazīragra and Odolekyga, make up roughly 9% and 11% of the population, respectively.

The east coast is primarily populated by Umbiers. "Umbier" is an umbrella term referring to virtually any Wazhenaby of Belisarian descent, but specifically refers to the Umbiåns-speaking, Ottonian-descended ethnic group with roots in the 17th century Otomarcan invasion of the Sevens Fires Council. People self-identifying as Umbiers made up about 10% of the population in 2020.

Additionally, there are numerous populations, ranging from small minorities to immigrant communities, which do not fit into any of these groups, totaling approximately 8.5% of the population in 2020. For example, the Enyaman immigrant population, which has surged since the beginning of the Enyaman Civil War, or the Måsakåkwa Nation, a small ethnicity in southern Meskosin which is related to the Michikawak.

Languages

While Wazheganon has no official language at a federal level, Dowazhabymowin is spoken by the vast majority of the population as a lingua franca and used in most official proceedings. Dowazhabymowin is also widely spoken in Awasin and parts of Rökkurlynd. There is significant divergence between dialects of Dowazhabymowin, while simultaneously there is a considerable degree of mutual intelligibility between Dowazhabymowin and other Kadowakan languages spoken in the region, such as Michikawy, Hesilī, and Jajigak'mawi, due to historical trade and intermarriage. Thus, some linguists classify these languages as dialects within a single tongue, although this remains controversial. If the Kadowakan languages are considered fully separate, then Michikawy is the largest first language in the country, followed by Dowazhabymowin, then Umbiåns.