Administrative divisions of Themiclesia

The administrative divisions of Themiclesia are geographic entities responsible for both autonomous government and implementing the decisions of the central government. Themiclesia is a pluralistic state with varying types of regional autonomy: the states are mostly autonomous .

Terminology

The concept "sovereign territory" is generally translated as krjangh (境; 竟 in monumental style) in Shinasthana, though this is not a perfect translation. The latter conveys the meaning of "border, limit" more accurately, cp. Latin limes, "limit, border". Another term, pran-do (版圖) is also seen occasionally, though this term literally means "household records [and] land surveys", referring to the area in which the government exercises administrative control. The term gwrên-kwar (寰官) refers to the area in which agricultural revenues are paid into the Great Exchequer (大內); as Themiclesia was primarily an agrarian state in the past, agricultural revenues were taken as the basis of statehood and used to judge the extent of the state's power. However, gwênh-kwar technically excluded alienated territories like the fiefs of peers and the palatine states. The same limitation existed for prong (邦), the term most often translated as "state". The word kwek (國), which survives in Menghean to mean "state, country", today means "region, periphery" in Themiclesia, with little political significance.

History

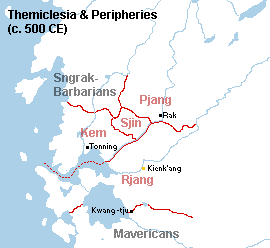

Antiquity

During Antiquity, Themiclesia-proper was dominated by dozens of city-states (邑, ′jep), which were ruled by their respective monarchs and aristocrats. The land around the city, usually owned and cultivated by the city's elites, was called the gwrên (寰). The combination of a city and its surrounding lands, called a "country" (邦, ke-prong), would form the basic unit of Themiclesian administration into the dynastic period beginning in 256. When a city controlled another through a colonial relationship or by conquest, tribute was exacted from the prong as a whole, as a city by itself was not economically productive in agricultural terms, while its surrounding lands often too large to police and tax.

If a conquered city lost its autonomy, as was more often the case into the Classical Period, it was often granted to the hegemon's supporters as rewards, but some were retained as the hegemon's demesne. Many such grants evolved into financial entitlements, giving the beneficiary all or part of the city's revenues, but the hegemon instead appointed magistrates to supervise the cities, as he did in the demesne. Regardless of the disposition of the city's ruler after conquest, it was rarely possible to remove the local aristocracy, and often their co-operation was sought instead. In Tsjinh in particular, the aristocracy of the mother city was particularly powerful, and the Tsjinh patriarch shared spoils of land and goods with his high nobles as a matter of course.

In the 3rd century, new settlements were often founded without the official title of "city" to avoid the alienation of power from the absentee ruler to a local aristocracy; in this case they were called gwrên and governed by a ringh (令) or "commandant". Large, poorly-settled areas were governed as provinces (郡, nkjurh); these are often considered under a nominally-military occupation rather than genuine administration. During the Sungh dynasty, regional administration was reformed after a five-year war exhausted the influence of the palatine princes, who ruled the northern half of Themiclesia-proper under their own right even though they swore allegiance to the hegemon. Viceroys (守, n′ju′) were appointed over the territories of the palatine princes, whose dominions were also called provinces, but the viceroy over a former palatine dominion was senior to the governor of an interior province.

Most scholars believe that the distinction between administration and ownership or title of land at the local level emerged during the late Antiquity to early Medieval period (2nd to 6th century CE), as a consequence of the sharing of local powers as well as opposition between an appointed magistrate and a hereditary owner of land. In addition to his economic role, most magistrates had impermanent terms by the end of the 4th century. This distinction emerged over several centuries, and even in the 6th century it was still not uncommon for a hegemon to grant both magisterial and manorial powers to a single person over a small city or a parcel of land. Under the efforts to strength finances and reward loyalists in the mid-5th century, it became the rule to appoint a magistrate to supervise and increase taxation whether that went to one of the hegemon's supporters.

Medieval

Emperor Ngjon was established as hegemon of Themiclesia in 543 due to his promise to reduce taxation, but he and his successors introduced a more vigorous local administration system in the reduced demesne of the emperor. In 552, he ordered the survey of all Themiclesian farms, a tremendous undertaking that took over 20 years to complete. Up to this point, taxes were collected by magistrates from whatever source he could find, and the co-operation of the major landowners and merchants was indispensible; their compliance was often compelled by the threat of military force. The collection of poll tax, the other common source of revenues, was laborious when there was little to no local bureaucracy. The new survey permitted his administration to levy taxation in a more controlled and centralized manner, often directly from the cultivator. This change is evidenced in the operation of a new unit of local administration—the manor or commune (里, rje), corresponding to the large estates held by aristocrats, whose contents were then opened to royal extraction.

The administration of provinces also evolved during the Mrang period, heavily influenced by the administrative techniques imported from Menghe itself. After the 6th century, new settlements came under the jurisdiction of the provinces in view of reserving revenues from them to the royal exchequer and the rights to appoint officials therein to the crown. This consideration created a two-tiered administration with a provincial marshal over a county magistrate that would become normal in Themiclesia after this time. In the 7th century, the viceregal provinces of the north were each divided into two to prevent any viceroy from gaining too much territory and power. By edict in 722, interior provinces acquired a civil administration headed by a viceroy parallel to the marshal.

Local government

In most places, there exists a two-tier system of local government; smaller entities usually serve an administrative function.

| Tier 1 | City ke-prong, (邦)[1] |

Municipality gwrên, (寰) |

Province nkjurh, (郡) |

State ke-prong, (邦) |

Region kwek, (國) | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Tier 2 | Commune skok, (區) |

Borough brji, (啚) |

District kraw, (交) |

Commune skok, (區) |

District kraw, (交) |

Township ta, (都) |

County gwrên, (寰) |

(Locally regulated) | District be, (部) |

| Tier 3 | Manor rje′, (里) |

Manor rje′, (里) |

Manor rje′, (里) |

Commune skok, (區) |

Manor rje′, (里) |

Manor rje′, (里) | |||

- ↑ Officially, all cities are referred to by name and not as a category.

First-level divisions

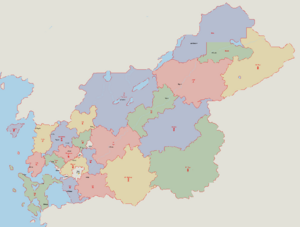

Themiclesia is divided into 33 first-level divisions. Except the 3 autonomous states and 2 regions in the north and east, there are 5 cities, 8 municipalities, and 15 provinces.

Province

The administration of each province (郡, nkjurh) is carried out by five offices: viceroy, marshal, tribune, principal secretary, and provincial council.

The viceroy (守, n′ju′) and marshal (尉, ′judh) are officers appointed by the Cabinet, and their modern roles are largely ceremonial. The viceroy's former duties included the administration of taxes, maintenance of the provincial census, and taking of accounts, and the marshal maintained the region's militias, appointed civil and military officers, and administered justice, though the last duty was carried out by a group of professional judges by the Medieval period. While the viceroy and marshal were co-heads of the province, the viceroy was regarded as the more senior due to its closer relationship with the central government. Both the viceroy and marshal serve at the pleasure of the Crown and in practice that of the central government, and terms of office are not guaranteed; scholars observe that re-appointments are the most frequent when a transition of government parties takes place at the central level, indicating that appointment as viceroy may be a form of political patronage.

The tribune is the chief prosecutor for the province and is responsible for the investigation of illicit activity. The tribune is appointed by the Crown on the advice of the Attorney-general, who is a government minister but is expected to provide impartial advice in this case.

The principal secretary (長史, ntrjang-s.rje) originated as the chief advisor of the viceroy and professional head of the provincial administration. He wielded considerable powers due to the transient nature of the viceregal office. After the Local Government Act of 1900, the principal secretary is always appointed after the approval of the Provincial Assembly. This officer is responsible for the ordinary administration of the province as well as the supervision of certain affairs conducted by secondary administrative bodies within the province.

The provincial council is the main legislative body of the province and dates to Medieval times. In a number of provinces, the council is bicameral.

Cities and municipalities

In Themiclesian administration, cities and municipalities cover largely the same kind urban area and some rural peripheries. The distinction between cities and municipalities is chiefly historical. Cities are technically independent polities that conceded some autonomy in exchange for protection to the royal government, while municipalities acquire their rights to self-rule by incorporation. The word for "city" also means "city-state" in Shinasthana, and the independence of cities is visible in legal language—they are always named individually and not treated as a class of administrative entities. Generally speaking, cities are not created, and newly incorporated urban areas are always municipalities.

The historic city included not only the built-up, urban area usually enclosed by city walls but also a swathe of surrounding land, which were often owned by the city's wealthiest citizens as a source of rental income; therefore, they are considered part of the city itself, not of the adjoining regional authority, and taxed and protected as such. Cities and municipalities could acquire a considerable number of exclaves through alodial transfer, which in the modern era must be recognized by Parliament; on the other hand, a desire for administrative convenience has also encouraged cities to sell distant exclaves to the central government, whereupon they would become part the local entity. The boundaries of many Themiclesian cities are exceedingly old.

States

The eastern part of the country is divided into a number of states (邦, prong), the

The government of the devolved state imitates the central government. The executive head of an devolved state is the chancellor (相邦, smjangh-prong), and there is usually also one vice chancellor (丞相, gjêng-smjangh).

List of first-level divisions

| Name | Kind | Area (km²) | Postal Code | Subdivisions | Capital | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Inner Region | 内史 | Metropolitan City | 3,106 | 10 | 57 | |||

| Gar-nubh | 河內 | Province | 19,084 | 11 | 12 | Grui | 懷 | |

| Kju-ngjon | 九邍 | Province | 22,555 | 12 | 13 | Lja′ | 輿 | |

| Sjin | 辛 | Metropolitan City | 341 | 13 | 22 | |||

| Lrjêng | 呈 | Metropolitan City | 552 | 14 | 43 | |||

| Gra | 邘 | Statutory Municipality | 425 | 15 | 35 | |||

| Ngakw | 濼 | Statutory Municipality | 297 | 16 | 17 | |||

| Gar-ngwadh | 河外 | Province | 18,448 | 17 | 8 | ′An | 安 | |

| Pek | 北 | Province | 54,710 | 18 | 11 | Le′ | 代 | |

| Spram | 般 | Province | 17,812 | 19 | 17 | Drjang-tsje′ | 長子 | |

| Rjem | 臨 | Statutory Municipality | 212 | 20 | 24 | |||

| Ning | 寧 | Statutory Municipality | 1,381 | 21 | 67 | |||

| Nem | 南 | Province | 21,629 | 22 | 20 | ′Ju | 幽 | |

| Dringh | 奠 | Metropolitan City | 680 | 23 | 32 | |||

| Prjin | 濱 | Province | 60,435 | 24 | 29 | Lja | 餘 | |

| Pa | 甫 | Statutory Municipality | 382 | 25 | 15 | |||

| Te | 夂 | Statutory Municipality | 220 | 26 | 26 | |||

| Rak | 雒 | Metropolitan City | 1,524 | 27 | 42 | |||

| Pjang | 房 | Province | 53,437 | 28 | 16 | K′jok | 曲 | |

| Sngw′jan | 泉 | Province | 106,412 | 29 | 22 | Smjang | 湘 | |

| Djang′ | 上 | Province | 175,968 | 30 | 7 | Kjung′ | 鞏 | |

| Gra′ | 下 | Province | 525,119 | 31 | 12 | Brjêng | 平 | |

| Lêng | 庭 | Province | 27,991 | 32 | 19 | Rjeng | 陵 | |

| L′jin | 申 | Statutory Municipality | 255 | 33 | 21 | |||

| Ladh-ngjon | 大邍 | Province | 47,711 | 34 | 14 | Rju′ | 柳 | |

| R′egh | 賚 | Statutory Municipality | 382 | 35 | 31 | |||

| Sngrak | 朔 | Province | 50,893 | 36 | 23 | Klêng | 經 | |

| N′ar | 堇 | Province | 43,374 | 37 | 16 | K.rjang | 京 | |

| Srum-l′jun | 三川 | Region | 119,713 | 38 | 8 | Trjung-ljang | 中陽 | |

| Brji | 毗 | Region | 75,182 | 39 | 4 | |||

| East | 東 | Region | 229,017 | 40 | 5 | |||

| Estoria | 端 | State | 213,980 | 60 | 12 | Apollonia | 亞捊鸞女 | |

| Helia | 宜 | State | 272,969 | 61 | 4 | |||

Second-level divisions

Counties

Counties (寰, gwrênh) compose of prefectures. There are 540 counties in total, each covering an area with around 20,000 to 40,000 people during the early 19th century, before Themiclesia urbanized due to industrialization. Currently, counties often fall between 30,000 and 60,000 people, as a result of rural depopulation, which remains an ongoing, albeit more sedate, process. The magistrate of a country, 寰令 (gwrênh-ringh) is elected.

Counties are considered the fundamental units of Themiclesian administration. Most counties known today were established before or during the Mrangh (543–752) and have remained remarkably stable in their borders and internal structures. Having a sedentary, agicultural culture, the arable areas of established county are unlikely to be changed except by irrigation works, which were largely handled by local labour and initiative. While county leaders were appointed centrally through most of history, assemblies, led by local gentry, possessed considerable influence over the implementation of central policies. Most civilian policies also occurred on the county level, and the prefectural militia also heavily relied on county-level administration.

Civic activities, such as the spring and autumn harvest festivities, were also organized by the county independently. Themiclesians are thus much more likely to have an affinity towards counties than prefectures.

Market counties

While rural counties steadily lost population, a handful of counties are much more populous than average because they contain urban areas. The capital city, Kien-k'ang County, has a population over 4 million; there are 34 other counties that have populations over 250,000. Such counties most often correspond to the site of the prefectural government or regional centres of commerce. In the local government reform of 1901, they became designated as city (都, ta), which are given some additional allowances in staff and budget to administer their larger population and to maintain urban conveniences. Urban environments became unsanitary and had inadequate social services during the period of rapid industrialization between 1860 and 1880; the reforms addressed these problems by establishing local clinics and subsidized pharmacies, which were administered by the county.

Third-level divisions

There are three types of third-level administrative divisions, the village (鄉, sk′jang), hamlet (邑, ′jep), and the commune (里, rje′).

Village

Villages are found in rural areas. The administrator of a village is called a village alderman (鄉良人).

Hamlet

A hamlet is usually a small town between 2,000 and 5,000 individuals.

Commune

Communes cover more densely settled locales, such as the local market or, in the case of an urban county, residential areas. The elected administrator of a commune is a commune administrator (里正). While the ordinary communes have around 2,000 to 5,000 invidiauls living in its jurisdiction, Kien-k'ang's communes may have as many as 50,000, which is as many as several counties or an entire urban county; this exceptional situation is provided for by specific legislation. In the early 19th century, parts of the walled area of Kien-k'ang remained very under-settled and were considered hamlets; however, by 1900, all hamlets became communes via settlement.

References