Crisis of the Ninth Century

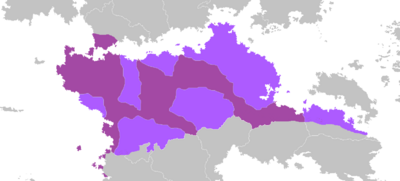

The Crisis of the Ninth Century', also known as the Burning Crisis or the Plague Crisis, was a period of immense civil unrest and political upheaval throughout the Makedonian Empire as a result of the Burning Plague and its aftermath. Lasting from 825-867, the Crisis saw roughly half the Empire's territory attempt to secede from Makedonian rule including all of Quenmin and Serikos, and significant parts of Knichus, Ruvelka, Mansuriyyah, and Arkoenn.

The Crisis began with the outbreak of the Burning Plague in Scitaria, which rapidly spread throughout Syara and wiped out between 15-25% of the Syaran population. Although the plague's rapid expansion and high fatality rate meant that it had largely passed on after just a few years, the resulting demographic decline and instability caused a severe curtailing in Makedonian power, exposing the institutional weaknesses of Makedonian rule over Siduri. Brief resurgences of the Plague throughout the 830s temporarily stifled rebellious strife, but no outbreaks equaled the devastation of the first wave and by 840 the resulting decline in Makedonian influence, the collapse of the Empire's internal trade network, and the loss of wealth inspired insurrections across the Empire's provinces.

In western Siduri, rebellions by the Hayren of southern Syaran and among the mountain kingdoms of Ruvelka immediately severed Makedon from its satrapies across Siduri. Rebellions of Arkoennite tribes along the Sundering Sea and in the central Siduri steppe further eroded Makedonian influence, while the decline of Makedonian manpower and resources allowed the Islamic Caliphates of Mansuriyyah to drive Makedonian forces out of central Mansuriyyah. The provinces of Knichus broke off completely, while in Quenmin the Tống Rebellion resulted in the establishment of an independent Quenminese state, and Han rebellions in Serikos effectively ended Makedonian influence in eastern Siduri.

The Makedonians gradually reconquered the break-away regions under the leadership of King Aristoxenus, beginning in 845 and concluding the final campaign against Serikos in 867. Aided by infighting between some of the rebellious provinces and usage of a "divide-and-conquer" strategy, Aristoxenus successfully restored the Empire to roughly its pre-Crisis borders. Many of the campaigns waged to reconquer the Empire resulted in large-scale loss of life and devastation to the contested regions, and by some estimates resulted in millions of civilian deaths.

The Empire never fully recovered from the Ninth Century Crisis and is widely considered the single biggest catalyst of the Empire's eventual fall. The resulting demographic decline resulted in decreased influence of Hellenic cultural practices across Siduri, further galvanized by ties with the Kingdom of Dragovita which set in motion the gradual Slavization of Syara. Manpower shortages forced the Makedonian military to rely even more on levy troops from its satrapies, and began shifting towards a more cavalry-centric force. In the Symerrian Peninsula where Ruvelka and Syara meet, the decline in ethnic Syara populations led to much of western Ruvelka being settled by ethnic Ruvelkans, triggering a gradual population change that would eventually form the basis for the modern border between the two nations. Coupled with the rise of Islam, the Zobethos faith gradually adopted a more monotheistic outlook rather than traditional pantheism.