Kingdom of Morinia

Kingdom of Morinia | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 425 CE–1075 CE | |||||||||||

|

Flag | |||||||||||

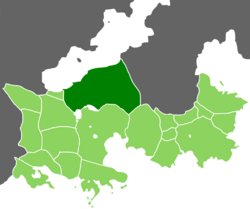

Morinia (dark green) among other Germanic (light green) in 550 AD | |||||||||||

| Capital | Tervanna | ||||||||||

| Religion | State cult of Týr Emendatic Christianity | ||||||||||

| Demonym(s) | Morinian | ||||||||||

| Government | Monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 425-432 | Chorcus Warhand | ||||||||||

• 1050-1075 | Lanfrid (last) | ||||||||||

| Legislature | Council of Elders (until 550) Morinian Diet (until 1075) | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Collapse of Tervingia | 425 CE | ||||||||||

| 1075 CE | |||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | Garima Drevstran | ||||||||||

The Kingdom of Morinia was a Tervingian successor state centered around the region of the same name in eastern Garima. It’s capital was Tervanna, an ancient Tervingian colony settled in the 1st century CE to serve as the “sea door to Suedia”. Under Tervingia, Morinia’s population was a mix of Gothic settlers and Suedian natives. At first part of the Saragetran Thing, it ultimately obtained the right to send representatives to the Thiudathing as a "Federated " constituent of the Empire.

During the “Warlord Era”, Tervanna’s own Council of Elders became the sole authority over the city and its territories, but it quickly lost its power to the Warchief. At first an elected position, by the end of the Tervingian Empire it had become a de-facto hereditary charge and were recognized as King by the ever weakening Saragetran Monarchy.

Morinia gained its independence in 425 CE after the Slavic Migrations. After countless battles against the incoming tribes, the Morinian Monarchy managed to keep the Slavs at bay in the Furodommark mountains and Lusatian Hills. From there, Morinia’s successive kings managed to push back the Slavs, expanding their control northward along Kulpanitsa’s shores, up to Halvari in modern day Drevstran. At its height, it maintained conflictual relationship with most of its neighbors: Suedia, with whom it competed over farmland and hegemony over the Lakes Regions and the Furodommark; Abodrita and the Pentapolis, both rivals for the control of the trade flux over the Lake; and the Slavic tribes themselves, who periodically refused to pay tribute to the Kings of Morinia and resumed raiding the Germanic kingdom. This constant warfare led to Morinia's slow decline over the next centuries.

In the late 8th century, the Lushyods arrived in Lake Kulpanitsa, both on boats and by land. Like other Kulpanitsan ports, Tervanna was threatened and ultimately plundered by the new invaders, while its Slavic vassals lost the Furodommark to them. In 810, the Lushyodorstag resumed its assaults on Morinia, pushing it back to its pre-425 borders. Morinia, Suedia, and Lusitia joined in an alliance against the Lushyods, to punish raiding parties and prevent further loss of lands. Despite its still important population and wealth, which made Morinia one of the major players in the Kulpanitsa region, their proximity with the Lushyodorstag and their status as bulwark against their aggressive expansionism meant that the Kingdom never had the opportunity to regrow from its loss and would only matter during the 9th and 10th century through its partnership with Suedia.

During the 11th century, Morinia at first joined the Germanic coalition against the Aulian Empire. But after the defeat of the coalition at the battle of Schwaburg, they were among the first states to swear allegiance to the western monarchs, to gain their economic and military support against the Lushyods. This marked the end of Morinia as an independent kingdom; however, the modern day Electorate of Morinia can be considered the continuation of the old medieval state.

Government and Military

The politics of Morinia reflected its origin as a warlord state: successful generals dominated all aspects of the Morinian public sphere and the perceived quality of a monarch was heavily tied to its ability to lead troops on the battlefield. Politics moved away from Tervinnia's council of Elders to the King's court and especially his High Command.

Nonetheless, Personages with clerical or scholarly abilities had roles to play within the state. Emendatic priests and monks often became advisors or secretaries for the king and his generals. Emendatic Monasteries became vital for the gestion of the country, especially outside of Morinia proper.

The army of Morinia inherited its traditions and organization from the Tervingian model. The basic units were the Wedges of 10 soldiers each, and 10 Wedges were grouped into a Party. Morinia was lucky in that its urban center, Tervanna, dwindled in size but did not completely dissapear like other grand cities of Tervingia. This allowed Morinia to raise armies as large or larger than most of its ennemies despite its relative small size compared to most of them. The demand in manpower and troop on Tervanna was also larger than on other settlements, as it was required that each Street of the capital levy a Wedge when called upon, making so that Tervanna's contribution to any war was proportionally and numerically far superior to any other settlement or region of Morinia.

Economy

Morinia's economy was dependent on the lucrative trade with the kingdoms on the other side of Lake Kulpanitsa, and the tribute paid by its Slavic vassals of the Furodommark. It thus traded wood, iron, gold, and other precious metals in exchange of goods like salts, dyes, and textiles.

Agriculture increased under the Kingdom of Morinia to the point that almost all lands under its control were cleared and turned into farmlands. This was made possible by the combined urban flight of German speakers and constant migration of slavic people. The traditional Tervingian agriculture, with long fallow period, was thus no longer suited to this intensive exploitation and agricultural cycles were redesigned to work with short fallows. The strain on the soils meant and "overpopulation" of the countryside meant that the Kingdom was multiple time victim of famins and plagues as any change in the environment could have dramatic effects on the cultures and thus the population. To compensate, the Morinian Monarchy during these crisis raised its tributes and launched raiding partie unto those who refused to pay or unto more fortunate neighbors. The aim was for the profits to be used to buy grains and cereals to be redistributed to the population. However, because of the limited administrative structure of the Kingdom, only the citizens of Tervanna enjoyed direct food distributions. Countryside villages and other settlements had to depend either on charitative efforts by the Emendatic Church or on their Landlords' own redistributions.