Administrative divisions of Themiclesia

The administrative divisions of Themiclesia are geographic entities responsible for both autonomous government and implementing the decisions of the central government. Themiclesia is a pluralistic state with varying types of regional autonomy: the states are mostly autonomous .

Terminology

The concept "sovereign territory" is generally translated as krjangh (境; 竟 in monumental style) in Shinasthana, though this is not a perfect translation. The latter conveys the meaning of "border, limit" more accurately, cp. Latin limes, "limit, border". Another term, pan-do (版圖) is also seen occasionally, though this term literally means "household records [and] land surveys", referring to the area in which the government exercises administrative control. The term gwrên-kwar (寰官) refers to the area in which agricultural revenues are paid into the Great Exchequer (大內); as Themiclesia was primarily an agrarian state in the past, agricultural revenues were taken as the basis of statehood and used to judge the extent of the state's power. However, gwênh-kwar technically excluded alienated territories like the fiefs of peers and the palatine states. The same limitation existed for prong (邦), the term most often translated as "state". The word kwek (國), which survives in Menghean to mean "state, country", today means "region, periphery" in Themiclesia, with little political significance.

History

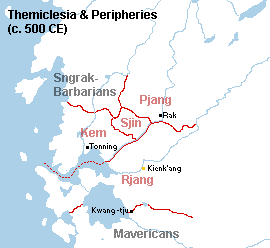

Antiquity

During Antiquity, Themiclesia-proper was dominated by dozens of city-states (邑, qrep), which were ruled by their respective monarchs and aristocrats. The land around the city, usually owned and cultivated by the city's elites, was called the gwrīn (寰). The combination of a city and its surrounding lands, called a "country" (邦, ke-prang), would form the basic unit of Themiclesian administration into the dynastic period beginning in 256. When a city controlled another through a colonial relationship or by conquest, tribute was exacted from the prong as a whole, as a city by itself was not economically productive in agricultural terms, while its surrounding lands often too large to police and tax.

If a conquered city lost its autonomy, as was more often the case into the Classical Period, it was often granted to the hegemon's supporters as rewards, but some were retained as the hegemon's demesne. Many such grants evolved into financial entitlements, giving the beneficiary all or part of the city's revenues, but the hegemon instead appointed magistrates to supervise the cities, as he did in the demesne. Regardless of the disposition of the city's ruler after conquest, it was rarely possible to remove the local aristocracy, and often their co-operation was sought instead. In Tsjinh in particular, the aristocracy of the mother city was particularly powerful, and the Tsjinh patriarch shared spoils of land and goods with his high nobles as a matter of course.

In the 3rd century, new settlements were often founded without the official title of "city" to avoid the alienation of power from the absentee ruler to a local aristocracy; in this case they were called gwrīn and governed by a ringh (令) or "commissioner". Large, poorly-settled areas were governed as provinces (郡, gun); these are often considered under a nominally-military occupation rather than genuine administration. During the Sungh dynasty, regional administration was reformed after a five-year war exhausted the influence of the palatine princes, who ruled the northern half of Themiclesia-proper under their own right even though they swore allegiance to the hegemon. Viceroys (守, qnuq) were appointed over the territories of the palatine princes, whose dominions were also called provinces, but the viceroy over a former palatine dominion was senior to the governor of an interior province.

Most scholars believe that the distinction between administration and ownership or title of land at the local level emerged during the late Antiquity to early Medieval period (2nd to 6th century CE), as a consequence of the sharing of local powers as well as opposition between an appointed magistrate and a hereditary owner of land. In addition to his economic role, most magistrates had impermanent terms by the end of the 4th century. This distinction emerged over several centuries, and even in the 6th century it was still not uncommon for a hegemon to grant both magisterial and manorial powers to a single person over a small city or a parcel of land. Under the efforts to strength finances and reward loyalists in the mid-5th century, it became the rule to appoint a magistrate to supervise and increase taxation whether that went to one of the hegemon's supporters.

Medieval

Emperor Ngjon was established as hegemon of Themiclesia in 543 due to his promise to reduce taxation, but he and his successors introduced a more vigorous local administration system in the reduced demesne of the emperor. In 552, he ordered the survey of all Themiclesian farms, a tremendous undertaking that took over 20 years to complete. Up to this point, taxes were collected by magistrates from whatever source he could find, and the co-operation of the major landowners and merchants was indispensible; their compliance was often compelled by the threat of military force. The collection of poll tax, the other common source of revenues, was laborious when there was little to no local bureaucracy. The new survey permitted his administration to levy taxation in a more controlled and centralized manner, often directly from the cultivator. This change is evidenced in the operation of a new unit of local administration—the manor or commune (里, rje), corresponding to the large estates held by aristocrats, whose contents were then opened to royal extraction.

The administration of provinces also evolved during the Mrang period, heavily influenced by the administrative techniques imported from Menghe itself. After the 6th century, new settlements came under the jurisdiction of the provinces in view of reserving revenues from them to the royal exchequer and the rights to appoint officials therein to the crown. This consideration created a two-tiered administration with a provincial marshal over a county magistrate that would become normal in Themiclesia after this time. In the 7th century, the viceregal provinces of the north were each divided into two to prevent any viceroy from gaining too much territory and power. By edict in 722, interior provinces acquired a civil administration headed by a viceroy parallel to the marshal.

Local government

Themiclesia is usually characterized as a unitary state despite the presence of devolved parliaments and governments accountable to them in the eastern interior. This is because the Parliament of Kien-k'ang has been consistently held by judicial authorities (last challenged in 2013) as having unlimited, sovereign power, above the devolved parliaments. That is, according to Trak and Mir JJ. writing in 1987, the parliaments of Helia and Estoria are creatures of the Parliament of Kien-k'ang, but their respective governments are not the creatures of the Government in Kien-k'ang.

In 1947, the Local Government Act or LGA (long title An act for the creation or amendment of the constitutions of divers local governments and to regulate their finances and several other purposes) was passed to give structure to the hitherto haphazard and peculiar forms of local government, created ad hoc by Parliamentary statute. Many cities were granted or recognized as having varying kinds of municipal powers over the course of the 19th and early 20th century, usually on the model of traditional local powers developed in prior centuries, but their relationships with the centrally-regulated provincial administrations were different in each case.

Under the modern LGA, last amended in 1986, there exists three types of local government with varying geographic extents and jurisdictional competences, called "regional", "municipal", and "communal". Depending on local practice and heritage, regional governments may be called provinces, royal commissions, or in the case of the area around Kien-k'ang, the Exchequer Department.

While in some literature these entities are described as "tiers" of government, this terminology is explicitly discouraged by the Themiclesian government, since municipal entities exist independently of and are not the creatures of regional entities. They also possess statutory competences independently of each other, and disputes between municipal and regional governments are usually resolved in favour of the municipality. Instead, the central government has preferred to describe the relationship between regional and municipal governments as co-equal "arms" of government specializing in different matters.

Prior to the LGA's passage in 1947, the smallest jurisdictions like wards and civil parishes were not nationally regulated but exclusively by municipal authorities; it was recognized, in some cases centuries earlier, that these positions were rife with nepotism and corruption, and their inclusion in national legislation was aimed at rectification thereof.

While there is a fairly distinct division of duties in most places between regional and municipal government, these are intertwined in the two largest cities of Themiclesia, Kien-k'ang and Rak. These two cities, with 13.1 and 4 million residents in their respective metropolitan areas, also have regional powers due to their sheer geographic size. In the case of Kien-k'ang, these powers are shared with the Exchequer Department, which (despite its name) is a province, and in that of Rak, shared with the Province of N'ar.

Division of duties

| Provinces | Metropolitan Cities | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Regional | Municipal | City | Commune | ||

| Education | Primary schools | ||||

| Secondary schools | |||||

| Trade schools | |||||

| Vital statistics | Birth and death registration | ||||

| Probate service | |||||

| Marriage and divorce | |||||

| Enrolment of electors | |||||

| Hygiene | Waste collection and disposal | ||||

| Sewerage systems | |||||

| Roads and vehicles | Public roads and bridges | ||||

| Vehicle registration and testing | |||||

| Public safety | Police service | ||||

| Prisons and juvenile correction | |||||

| Parking regulation and enforcement | |||||

| Building inspection | |||||

| Fire service | |||||

| Public amenities and culture |

Libraries | ||||

| Forests, parks, and greens | |||||

| Cemeteries | |||||

| Sporting and gaming | |||||

| Affordable housing | |||||

| Orphanages | |||||

| Retirement homes | |||||

| Urban planning | |||||

| Public transport | |||||

| Water draining | |||||

| Businesses | Hotels and inns | ||||

| Alcohol licenses | |||||

| Theatres, cinemas, etc. | |||||

| Armed forces | Militias | ||||

Schematic

| Regional | Province | Royal Commission | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metropolitan City | |||||

| Municipal | Township | City | County | District | |

| District | |||||

| Communal | Wards or Civil Parishes | ||||

Regional divisions

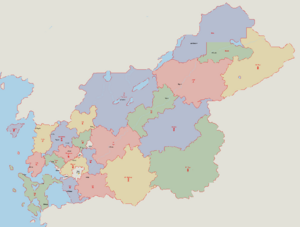

Themiclesia is divided into 29 regional divisions—8 provinces, 2 metropolitan cities, 5 royal commissions, and 2 colonies.

Province

Provinces (郡, gunh) by law have two principal officers, the Viceroy and Justice.

The Viceroy (守, n′uq) and Justice (㷉, ′uts) are appointed by the Emperor upon the advice of the Cabinet, and these two officers have largely ceremonial roles in modern practice. The viceroy's legal portfolio originally mirrored that of the central government and encompassed administration of taxes, maintenance of the provincial census, taking of accounts, the marshalling of provincial militias, suppression of violence, and appointed civil and military officers in the province. Over the centuries, these powers were either centralized or came to be subject to central review.

The Justice specialized in juridical matters and was, for some time, the chief judicial officer in the province. But this duty was gradually supplanted by a panel of more professional judges, also appointed centrally, and the justice became more involved in the execution of laws, in which he was a deputy of a kind to the viceroy.

After 1916, the viceroy's power to appoint military officers and command units raised under viceregal authority was subject to the direction of the Secretary of State for the Forces and, in practice, the Consolidated General Staff, since the provincial units were being integrated to form the Consolidated Army. Until the passage of the LGA, provinces did not have genuine local governments but were merely the administrative divisions of the central government; this stood in contrast with the cities, most of which had considerable local autonomy by 1920. A Provincial Assembly was created in each province in 1921, though provincial ordinances were passed exclusively under the viceregal authority.

While the viceroy and justice were co-heads of the province, the viceroy was regarded as the more senior due to its closer relationship with the sovereign. Both the viceroy and marshal serve at the pleasure of the Crown and, in practice, that of the central government, and terms of office are not guaranteed; modern researchers observe that re-appointments are the most frequent when a transition of government parties takes place at the central level, indicating that appointment as viceroy may be a form of political patronage.

The principal secretary (長史, ntrang-req) originated as the chief advisor of the viceroy and professional head of the provincial administration. He wielded considerable powers due to the transient nature of the viceregal office. After the Local Government Act of 1947, the principal secretary is always appointed after the approval of the Provincial Assembly. This officer is responsible for the ordinary administration of the province as well as the supervision of certain affairs conducted by secondary administrative bodies within the province. The provincial council is the main legislative body of the province and dates to Medieval times. In a number of provinces, the council is bicameral.

The tribune is the chief prosecutor for the province and is responsible for the investigation of illicit activity. The tribune is appointed by the Crown on the advice of the Attorney-general, who is a government minister but is expected to provide impartial advice in this case. Due to the evolution of the judicial system, local courts no longer participate in most civil and criminal cases and are only involved in family law, probate law, and coroners' inquests. Despite this contraction of jurisdiction, it is the viceroy's duty to appoint local judges in his capacity as the representative of the monarchy in the province. The viceroy must appoint judges according to the National Judicial Council, which is an independent body making recommendations to the benches of local courts to ensure impartiality and professionalism.

Cities and municipalities

In Themiclesian administration, cities and municipalities cover largely the same kind urban area and some rural peripheries. The distinction between cities and municipalities is chiefly historical. Cities are technically independent polities that conceded some autonomy in exchange for protection to the royal government, while municipalities acquire their rights to self-rule by incorporation. The word for "city" also means "city-state" in Shinasthana, and the independence of cities is visible in legal language—they are always named individually and not treated as a class of administrative entities. Generally speaking, cities are not created, and newly incorporated urban areas are always municipalities.

The historic city included not only the built-up, urban area usually enclosed by city walls but also a swathe of surrounding land, which were often owned by the city's wealthiest citizens as a source of rental income; therefore, they are considered part of the city itself, not of the adjoining regional authority, and taxed and protected as such. Cities and municipalities could acquire a considerable number of exclaves through alodial transfer, which in the modern era must be recognized by Parliament; on the other hand, a desire for administrative convenience has also encouraged cities to sell distant exclaves to the central government, whereupon they would become part the bounding entity. The boundaries of many Themiclesian cities are exceedingly old.

States

The eastern part of the country situates two States (邦, prong), Estoria and Helia. The government of the devolved imitates the central government and possesses very broad legislative and executive authority. The executive head of an devolved state is the chancellor (相邦, smjangh-prong), and there is usually also one vice chancellor (丞相, gjêng-smjangh).

Royal Commissions

List of primary divisions

| Name | Type | Area (km²) |

Population (2015) |

Density (persons/km²) |

Postal Code |

Secondary divisions |

Capital | Notes | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exchequer | 內吏 | Province | 40,638 | 3,920,000 | 2,871.86 | 10 | 15 | Slwal | 橢 | |

| Kien-k'ang | 建康 | Metropolitan City | 9,084 | 12,240,000 | 69.90 | 11 | 51 | Kien-k'ang | 建康 | |

| Rāk | 雒 | 1,524 | 4,780,000 | 3,136.48 | 12 | 42 | Rāk | 雒 | ||

| Ku-ngwyan | 九邍 | Province | 22,555 | 1,674,000 | 74.22 | 13 | 13 | Sin | 辛 | |

| Nēm | 南 | 21,629 | 892,000 | 41.24 | 14 | 20 | Ndringh | 奠 | ||

| Pāng | 房 | 53,437 | 576,000 | 10.78 | 15 | 16 | Kak | 曲 | ||

| Spram | 般 | 17,812 | 1,320,000 | 74.11 | 16 | 17 | Mu | 每 | ||

| Lra | 余 | 21,629 | 892,000 | 41.24 | 19 | 20 | Neks | 匿 | ||

| Prin | 賓 | 60,435 | 2,430,000 | 40.21 | 20 | 29 | Te | 之 | ||

| N′ār | 堇 | 43,374 | 927,000 | 21.37 | 22 | 16 | Sn'i | 爾 | ||

| Lat-ngwyan | 大邍 | 47,711 | 920,000 | 19.28 | 23 | 14 | Tups | 對 | ||

| Pēk | 北 | 54,710 | 492,000 | 8.99 | 24 | 11 | Qeng | 雍 | ||

| Līng | 珵 | 27,991 | 647,000 | 23.11 | 25 | 19 | R'ats | 燤 | ||

| Sngrak | 屰 | 50,893 | 1,053,000 | 20.69 | 26 | 23 | Kngrak | 屰 | ||

| Dang′-tāq | 上土 | 721,968 | 1,023,000 | 5.81 | 27 | 7 | Ngar | 元 | ||

| Srum-l′un | 三川 | 119,713 | 682,000 | 5.70 | 30 | 8 | Sin-kiks | 新冀 | ||

| Ghwrāng | 衡吏 | Royal Commission | 75,182 | 173,000 | 2.30 | 39 | 4 | |||

| Krya | 呂吏 | 229,017 | 27,000 | 0.12 | 40 | 5 | ||||

| Būi | 緋吏 | 272,969 | 126,000 | 0.46 | 41 | 4 | ||||

| Tral | 萬吏 | 213,980 | 208,000 | 0.97 | 42 | 12 | ||||

| Rēi | 豊吏 | 272,969 | 126,000 | 0.46 | 43 | 4 | ||||

| Estoria | Dominion | 213,980 | 208,000 | 0.97 | 60 | 12 | Estoria | |||

| Helia | 272,969 | 126,000 | 0.46 | 61 | 4 | Apollonia | ||||

Local divisions

Local divisions in Themiclesia consist of Counties and Townships in Provinces and Communes, Boroughs, and Districts in Metropolitan Cities and Statutory Municipalities. Historically, provinces were established in areas without major cities (and their aristocracies), making them easier to control centrally; however, many small settlements have since expanded, especially since the start of the Industrial Revolution. While provinces were convenient administrative areas for the purposes of collecting taxes and raising militias, it was ultimately with the nearby city or town that most of the political class identified. Thus, both urban and rural areas exist in provinces, some of which also grew to encompass cities that were not originally part of provinces, as cities could lose their independence if they failed to maintain a working relationship with the imperial court.

Counties and Districts

Counties (寰, gwrênh) and Districts (kraw, 交) are found in mostly rural areas. They are governed by an elected mayor and council and are responsible for much more than their urban counterparts.

Townships and Boroughs

The historic difference between Townships (邑, ′jep) and Boroughs (鄙, brji′) is that a township is a town under provincial jurisdiction but has acquired some independence from its the province, which usually happened when a town has acquired a stable group of civic leaders and are able to police and tax itself. In this way, towns were able to reduce royal expenditure on administrative costs and thus bargain for a degree of autonomy. A borough arose in a similar situation but within the precincts of a Metropolitan City, creating a subordinate town close to a major city.

References