Passenger rail transport in Themiclesia

Rail transport in Themiclesia originated in 1829 for shipping coal and now encompasses a large network of railways serving both passengers and freight. Inter-city railways grew with government support from 1853 and accompanied the Industrial Revolution to support long-distance commerce and modernizing manufacturing needs; these inter-city railways were bought by the government between 1892 and 1898 to prevent the laying of redundant railways, but private companies continued to operate trains on nationalized railways and branch lines. Improved revenues were taxed by the government to support expansion and maintenance of infrastructure. Urban railways and trams appeared the late 19th century. More recently, branch lines have seen development, and a high speed rail with speeds up to 300 km/h was introduced in 1967.

Despite a decline in ridership in the 1960s, the railway continues to be a principal means of both urban, suburban, and inter-city travel in Themiclesia. Inter-city transport is mainly offered by National Railway, a joint venture of public and private investment, but excursion trains are regularly operated by private companies. The railway accounts for nearly half of all inter-city freight by weight, but less by value as it is better suited to bulk goods in loose or containerized format.

History

Bronze avenue

Historical sources report that bronze plates were installed in 570 in the grooves on the royal avenue, which led from the Sk'ên'-ljang Palace and extended about 2 km southwest to the Skor-ljang Gate. For this reason, the royal avenue was also called the "bronze avenue", and it was received as evidence of the wealth and power of the monarch. Such bronze plates would have made the grooves leveller, especially in contact with the bronze-surfaced wheels of royal carriages at that time, but there is no evidence of such practice outside of this specific context, and it has evidently not been retained therein for long.

Mining railways

The first railway in Themiclesia was laid down in 1831 by Asikainen, a Hallian company oeprating a coal mine in Predh. The company had relied on draft animals and barges to ship its products into the Meh but found a more profitable mine away some 16 km from the river, which a railway covered. The line was operated with a single locomotive, the Kaveli. The introduction of the railway made Asikainen more profitable than others relying on draft animals, and by 1840 no fewer than eight mining operations utilized railways in the Themiclesian north, where mining rights have been leased to Hallia through the Treaty of Kien-k'ang of 1796.

In 1844, a railway from Predh to Gra was opened, which allowed Hallian merchants to undercut coal from Themiclesian mines, transported by draft animals. This coal was not tariffed as it was not technically imported, but it became a political crisis at the lobby of Themiclesian coal mines and merchants, who argued that the Hallian miners were outselling domestic miners. In 1847, the government responded by awarding land to Themiclesian mines that they might lay their own lines, and a testing railway was laid down between the market town of Ngek and Kien-k'ang in 1849, spanning 65 km.

Private era

A royal commission was issued at the same time to study the effects of railways on foreign states, with the conclusion that an efficient transport system allowed more goods to be marketed domestically and would be an incentive to investment in businesses. The government also saw value in a railway system as a component of defence logistics, as troops could be moved around the country more rapidly and without requisitioning goods from the towns they passed through. As a result of the initially-good results of test railway and of the recommendations of the royal commission, the building of railways became the Rjai-ljang government's policy. New railways were constructed with government grants in land and backed by high-interest bonds sold to the government. In 1855, the first inter-city railway over 300 km opened between Kien-k'ang and Tor.

In 1854 and 1855, both Menghe and Dayashina agreed to elimiate trade barriers with foreign states, with the result that the trinity of Themiclesian exports—porcelains, tea, and silks—now faced stern competition. Themiclesian exporters became uncompetitive at Casaterran markets, triggering the Depression of 1857, which rippled to railway bonds as the first railways struggled to generate sufficient revenue to cover interest rates. Facing dwindling customs revenue, the Rjai-ljang government diverted its money to stimulate other industries and could not continue to support the building of railways. The first wave of railway-building thus came to a sudden halt in 1858.

Themiclesian industry regained some footing in the early 1860s. Indeed, some exports were so astonishingly successful that a trade war began in Camia over Themiclesian goods, triggering the Battle of Liang of 1867. Themiclesia's defeat resulted in the lifting of tariffs on Camian and Maverican grains. The importation of cheap grains caused a severe depression in agriculture, forcing landlords to evict tenants who then flocked to the cities in search for work, in turn depressing labour prices and supporting the growth of manufacturing businesses. However, new railways were built to transport grain from docks to the cities that experienced population boom, and manufacturing businesses also relied on railways to source raw materials from the countryside. These factors promoted a second, largely privately-funded drive to build railways in the 1870s.

The 1850 – 60s also saw the first regulations appear over travelling conditions and amenities. In 1843, it had been legislated that railways shall not carry passengers in "vehicles not made for the transport of mankind", to deter mining railways from carrying them in coal wagons or on carriage roofs, but the law did not impose penalties and so had little effect. This requirement was made operative in 1857 by requiring each operator to inspect the structural soundness of its coaching stock annually. In 1861, third-class passengers obtained rights to seats, a roof above the compartment, and openings for lighting and ventilation, but this did not require glazing, a hole in the carriage wall being judged sufficient. In 1864, the Railways Act required railways to charge no more than 1 grain per Imperial mile travelled. Though facilitating urbanization, fare restrictions also discouraged railways from offering improved coaches in third class.

The only railways that received government funding in this era were ones connecting mining towns in the northeast to the Themiclesian heartland, as distances were too long for private investment to cover; additionally, the government welcomed the establishment of businesses in the distant countryside, as it was seen to ward away territorial claims by other powers. Under these auspices, the Great Northeastern Railway was completed in 1884, extending over 2,200 km to reach ′An from Rak. In these, the government took an interest in tariffing goods shipped but did not interfere with their operations.

In terms of railway operators, the operator and coachbuilder Lower Themiclesia Railroad (LTRR) achieved renown for its sleeper coaches that debuted in 1871 but national dominance after the nationalization of major railways. Through services from Kien-k'ang to Sngrak and later to ′An required multi-day travelling times in the 1880s, when trains travelled about 25 mph on average, though speeds up to 40 mph were possible on superior sections. LTRR also accrued considerable profit from exporting its exquisitely-appointed rolling stock, nicknamed "palace cars" on foreign railways; to accomplish this, it employed skilled artisans, some from manufacturers of porcelains and luxury fabrics. Though these exports were successful, it soon sparked competition, most notably in Tír Glas and adjoining states, and the domestic market remained its main source of revenue.

Regulated era

By 1890, revenue mileage of main and branch lines in Themiclesia reached 11,520 km. Railroad had been largely an unregulated business, as it was assumed that the demands for goods would guide them towards building efficient lines. But signs of financial difficulties appeared in 1888 when the National Trunk Railway between Kien-k'ang and Lrjeng failed to earn profits as anticipated, largely because another railway already served the nearby city of Gra and a third Ngrakw. These existing railways took advantage of a link line and competed with the National Trunk by cutting prices or providing rebates. By 1891, the National Trunk was bankrupt, having taken millions from investors and failing to provide a single dividend; the government was called upon to save the National Trunk. The purchase, challenged in Parliament, resulted in a general survey of railways to determine whether the causes underlying National Trunk's bankruptcy were common.

In 1892, a new law was passed forbidding the building of "railways in close proximity" while the government undertook to purchase the failing National Trunk by issuing bonds in expectation of extending the road to Loi and then Sn′ji. From 1892 to 1895, the government purchased a large number of failing railroads and worked to extend their lines to different areas in the hopes that more freight would be diverted through them and generate revenue. The acquired lines were transferred to a new corporation called the National Railway Company, which was funded through both stocks and bonds and acquired the staff and assets of the struggling roads it superseded. The roads that were not acquired were permitted to use the NRC's lines for a fee. Though this purchase programme was not financially rewarding in its initial years, revenues increased in the 1900s that more railway bonds were sold, enabling the government to purchase controlling stakes in the majority of long-distance railways.

Many private railroads understood this government policy as an attempt to drive them out of business, though the new railway had the considerable advantage of providing through service that had not existed before, particularly through the Central Junction Railway of Kien-k'ang. The Public Railway Act was passed in 1893, requiring the National Railway Company (NRC) to provide passenger services on all its lines in both directions, every day, and three classes of service on inter-city railways. To compete with the NRC, the Northwestern Railway was formed by the merger of four shorter roads in 1898, and the Maritime Railway in 1899. These two roads each underwent internal restructuring to abolish parallel lines and achieved considerable economies. The Northwestern Railway merged with the the Great Northern Railway to form Themiclesian Railway in 1898, while National purchased Maritime Railway to form the National and Maritime Railway in 1902.

By 1906, the process of consolidation had created two major railways—Themiclesian, and National & Maritime. In 1903, the Government acquired the power to decide what was a "railway in close proximity", though one decision would be equally applicable to both railroads. Under these conditions, five more direct railways were built between 1903 and 1923, as the law did not prohibit the building of more efficient lines that connected cities; indeed, the building of railways accelerated in this period as the law all but guaranteed that, once one company was in control of one route, the other was shut out of it. On the other hand, the two operators owned largely-parallel railways on the Rak–Sn'i–Rap–Tubh–L′in corridor and both had routes into the capital city of Kien-k'ang.

In the first decade of the 20th century, both Rak and Kien-k'ang began construction of urban rail transit. These railways had both above-ground and underground sections and required the co-operation of the city to complete railways in densely-populated areas, and a large number of evictions occurred in both cities. The development of urban railways had a profound influence on demographics in both cities, making longer commutes practical and, in the long term, encouraged suburbanization. These railways also competed with horse-drawn omnibusses and electric tramways. Unlike inter-city railways, urban railways were largely unregulated by the national government and fell under the purview of city councils. In this wise, the councils, controlled by the wealthier classes, usually objected to the laying of lines into or across elite neighbourhoods to reinforce segregation amongst classes.

Wartime

After the imposition of national mobilization to repulse the Menghean and Dayashinese invasion, inter-city railways were nationalized in 1937 to support the war effort. Themiclesian Railways and National & Maritime continued to be operators on the nationalized rail network, but government trains took priority, and rolling stock from both entities were regularly commandeered by the government. From 1936 to 1938, Menghean forces utilized forced labour, largely of prisoners-of-war of Casaterran descent, to construct a railway from Menghe to Themiclesia, through Dzhungestan, to ease a logistics bottleneck that had barred further deployment. Occasioning thousands of fatalities, the railway was called the "railway of death" by survivors of its construction. By the end of 1940, it is estimated that over 60% of intercity railways were under enemy control, though a number of key points such as sheds and bridges were demolished prior to their capture, and locomotives and rolling stock had been evacuated as much as practical.

During the war, the railway networks of both operators suffered considerable damage, some self-imposed. In 1947, the two railways merged to form the National & Maritime & Themiclesian & Northwest Railways but operated under the trade name of National Rail. This new corporation operated under Parliamentary charter and was required to re-invest a portion of profits into maintenance, employee welfare, and fare reductions before dividends could be paid to shareholders; to stimulate investment, the government reimbursed dividends paid to it as the major shareholder for the first 40 years of its operation. To compensate for damages to its infrastructure, the armed forces were ordered to transfer the industrial spurs it had constructed to National Rail.

Postwar

To expedite the export of Themiclesian goods to Maverica and Menghe, the Trans-Hemithean Railway was completed in 1952 with the support of all three governments. A train could travel from Kien-k'ang to Sunju in 79 hours on this route, outpacing shipping by days. Despite its principal use as a freight railway, passenger service was also provided on this road, though it soon faced stern competition from airliners. National Rail ran its premier train on the THR until its closure in 1959 due to Communist revolution in Maverica.

The earlier years of the post-war period were dedicated to the restoration of the railway, with steam adhesion assumed to remain indefinitely; however, by 1953, this policy came under attack by some directors on National Rail's board. It has been asserted that diesel locomotives, though not more powerful individually, were more efficient and required less maintenance. Such a change, however, was contested by workers' unions, who argued that the abolition of steam power would result in redundancies. Thus, the propagation of diesel power would proceed incrementally, from the main lines to branch lines, where steam locomotives remained in operation until 1971. Even though diesel was accepted by National Rail in 1955, experimentation on more efficient steam locomotives continued until the 70s, and new ones were ordered as late as 1959. Steam power was withdrawn from main lines in 1961.

Despite economies achieved by dieselization in the 50s, railways faced competition from air and road voyage, especially after the opening of Themiclesia's first controlled-access highway in 1949. This prompted a desire for higher speed that existing lines were considered incapable of providing due to routing issues. National Rail, in co-operation with its analogue in Dayashina, tabled a plan for an electrified main line that would support speeds not then obtainable on conventional railways. As proposed in 1957, this system was to be the sole electrified line in Themiclesia, since diesel was envisioned as the principal means of adhesion on other lines. As a parallel railway, the plan received sanction from Parliament in 1959, and work began in 1960. There was rumoured an informal competition between Dayashina and Themiclesia to realize their respective plans for high-speed rail, though Dayashina was to best Themiclesia by more than three years.

The first high-speed electrified line in Themiclesia opened in late 1967 after numerous delays and were capable of supporting speeds up to 230 km/h (140 mph). The expansion of the high-speed railway was continued after the first line, as a fixed portion of revenues from the high-speed service funded further construction. At the same time, the 24,525-kilometer network was subject to pruning in order to conserve expenditures. These cuts would eventually lead to the abandonment or sale of a quarter of that network by 1983. Sale of land occupied by railways became an important source of revenues for National Rail, but there were concerns that it was an unsustainable source.

Car ownership and intercity driving became more common in Themiclesia after the extension of motorways in the 50s and the Affordable Car Act of 1960. Such changes in travel preferences created persistent losses for National Rail, which had operated profitably until 1964. Losses prompted management to seek partial deregulation in pricing models and mandatory services on unprofitable lines. National Rail was required by charter to provide three classes of service all main lines, every day, and in each direction, until 1970; since then, National Rail has aimed to catered more specifically to segments of the clientele, no longer viewing its products strictly as a public service. This redirective approach to business was credited to Lord Kal, President of the Board from 1968 to 1977.

From 1972, first-class travel was withdrawn from all except the most popular routes. In 1976, third-class travel was abolished on long-distance services, accompanied with a reduction in the tariff for second class. This decision the Progressive Party, then governing, hailed as vindication for the free market's ability to improve products, but railway historians have noted that a small but considerable number of patrons were compelled to pay more to travel second-class instead. Additionally, National Rail's new rolling stock purchased since the late 80s have seen reductions in the quality of a second-class service. Third-class travel remained on regional trains, and it is not unknown for frugal travellers to connect to several regional services in order to travel at a third-class rate even at long distances; other travellers embraced bus voyage instead. These attempts at product differentiation eventually gave rise to the modern class system on the National Rail network.

While these changes have curtailed losses to some extent, National Rail continued to operate at a loss until 1989, when further changes to market position and pricing strategy took place. As suburban branch lines were some of the least profitable parts of its operation, these were sold or leased to municipalital operators, who were often more willing than National Rail to provide investment to renew ageing infrastructure as part of political mandates. This policy has not been universally successful, since many municipalities still relied on subventions from Kien-k'ang to provision services or made considerable cuts to operations since taking over. Truncation of branch lines allowed National Rail to liberate more funds towards inter-city services and regional trains; however, the desire to maintain an exclusive market share for high-speed rail has also imposed a ceiling as to the speeds obtainable on conventional routes.

Classifications of rail transport in Themiclesia

By law, all entities that create, own, and operate railways and rail vehicles that are capable of carrying persons or goods must be registered with the government to ensure that safety standards are met. This does not depend on the scale or liveliness of the railway: ridable miniature railways and railways closed for business are still required to be registered and inspected regularly.

Inter-city

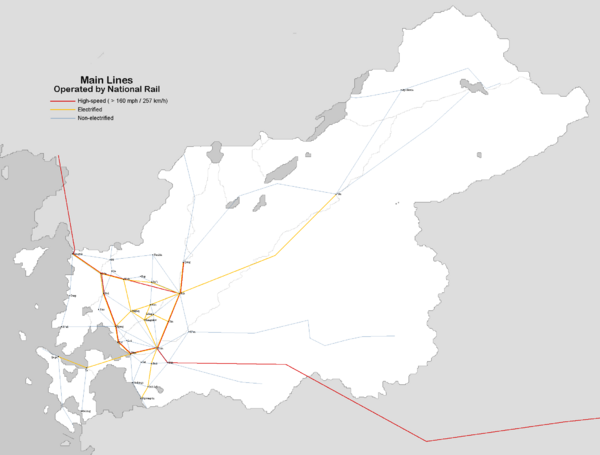

National Rail is the trade name of National & Maritime and Themiclesian Northwest Railways (邦海眔辰旦𣁋道), which was formed in 1947 by the merger of National & Maritime with Themiclesian Northwest under the auspices of the government. The company is jointly owned by the government, as the major shareholder, and private investors, and its shares are publicly traded under the symbol NRC in L'odh Stock Exchange. It is incorporated by act of parliament that specifies certain rules and obligations, which are imposed in view of the corporation's monopolistic ownership and operation of the nation's inter-city railways. Its board of governors are not permitted to declare dividends for shareholders unless it has met required thresholds in maintenance, employee welfare, and fare reduction, and in return the Government disburses its share of dividends, if any are declared, to National Rail.

National Rail owns and operates all inter-city railways in Themiclesia, a market position inherited from its predecessors that have purchased all other major railways in Themiclesia by the 1920s. It provides passenger and freight service throughout its network. National Rail's incorporation bears similarities to utility companies prior to its emendation in 1970, requiring it to provide a certain quantity of services at a stipulated frequency on all its routes. These rules have since been partly lifted, allowing it greater flexibility in allocating its resources and improving profitability. However, this has also resulted in the closure of a multitude of branch lines, some being central to the convenience of smaller towns not adequately served by other means of transport. National Rail is also the largest landowner in Themiclesia after the Crown, and a considerable portion of its revenues are derived from leases and development projects.

This corporation also does business with the trade name Themiclesian High Speed Rail, a service begun in 1967 on dedicated lines for rapid inter-city transit with speeds now up to 300 km/h.

Urban and suburban

Many Themiclesian cities possess urban railways, and most began as private ventures that serviced the demand for intra-urban transit, rarely transporting freight. Competition was fierce in the city of Kien-k'ang, which pushed 2 million inhabitants in 1900, resulting in some parallel lines, but development of urban transit elsewhere lagged behind considerably. In Rak, the urban railway and tramway were owned by the same company, and tramways, being the cheaper to construct, serviced areas that would not justify railways. By 1957, most major cities had unified its urban railway and tramways under single providers, though sometimes the two were distinct.

Suburban railways, which extend further beyond the limits of the city, are not always grouped under a single provider. In Kien-k'ang, a single corporation operates all suburban lines near the city, but Rak's suburban railways are operated separately by Omni Rail and Rak Regional Transit. Many suburban railways were formerly branch lines operated by National Rail, but since the deregulation of 1970, many have been sold to cities and private railways.

Other private railways

There are 57 registered private railways in Themiclesia, with different business models: some privately own tracks and rolling stock, while others own neither and are purely operators. Private lines encompass both passenger and freight transit, and they may be specialized for tourism, industry, or other purposes. Several mining companies own battery-powered railways for transit within mines, though this is not commonplace today. While there are no forest railways or agricultural railways still in use for their original purposes today, a number have been reconfigured as tourist attractions. The majority of private railways are freight operators whose primary business is the transport of goods from spurs to freight depots through National Rail's network. There are also tourist train operators that provide rail cruises on luxury rolling stock.

Miniature and amusement railways

Common features on Themiclesian railways

Railways in Themiclesia are subject to a number of legal constraints passed mainly to promote efficiency in rail transport and enhance safety. Many early regulations were made by Parliament, by whom most early routes were also authorized; however, the regulation of railways often became political, and varoius bodies such as the Board of Trade and later Ministry of Transport also became involved. Most modern regulations are made by ministers with statutory authorization, but basic regulations such as the track gauge for intercity railways are fixed by statute.

Units

The standard system of measurement on Themiclesian railways, for internal purposes, are Imperial units from Anglia, as much of the technology and rolling stock on the earliest non-Hallian railways were imported from Anglia. Railway lengths are signposted in terms of Imperial miles and chains. The descriptor "Imperial" (rendered phonetically as 音卑麗, rf ′im-pi-ryal) is added to the corresponding Themiclesian unit. However, to anticipate unexpected changes by Anglia, which have not yet happened, Imperial units in Themiclesian railways were retroactively fixed by a domestic statute to their definitions on Jan. 1, 1870. Some old lines, once under Hallian operation, had their sign-posts changed from Hallian units to Imperial ones by 1896. However, in support of the Government's desire to promote the Metric system, that system has been in use for public trade since 1957.

Track gauge

Broad gauge

Several lines in the north were built for a 5 ft (1,524 mm) gauge, especially those owned by Hallian companies. As it was unlawful to re-gauge any standard-gauge railway to a different gauge, the last 5-foot gauge main line was converted to standard gauge in 1894. Nevertheless, it was permissible to operate a different gauge

The Northern Riparian Railway, located in Ladh-mgon Province and on the border with Nukkumaa, runs on a 5 ft gauge that is unique to operational lines. It was built in 1846 and serviced two coal veins located on the Themiclesian side of the river. The line was acquired by Northwestern Railways in 1896, but due to dwindling freight and passenger service, it was never converted into standard gauge. It was abandoned in 1919 but restored for tourism in 1960. The line today services open-air dome cars offering views of the river.

Standard gauge

The modern standard gauge on Themiclesia railways is 4 ft 8 1⁄2 in (1,435 mm), this gauge having been established in 1851 by the Rjai-ljang Government. Since that year, any railway measuring more than five miles between its most distant points was by law required to be built in this gauge, and all main lines currently operated by National Rail conform to it. Most branch lines and industrial spurs, which act as feeder lines for freight service on main lines, are also in this gauge.

Narrow gauge

There are several narrow gauges in Themiclesia, the majority built well after the 1851 law that established the standard gauge on lines longer than five miles. Narrow gauges were permitted on lines shorter than five miles and not connected to any standard-gauge line, but also longer railways not open for public business or for which public business represented a insignificant portion of its revenues. Likewise, they were permissible for tramways, which shared the road surfaces with non-rail vehicles. Narrow-gauge lines were often constructed in mines, farmland, factories, and private estates, where restrictive space or budget forbade the construction of wider railways.

In forests, where gradients tend to be steep and turns sharp, the 3 ft 6 in (1,067 mm) and 2 ft 6 in (762 mm) gauges were popular and accounted for the majority of forest railways. In the northeastern Kalami mountain range, there exists a 2 ft 6 in mountain railway. There are also a number of "tourist rails" that carry tourists from one attraction to another, built in the early 20th century, that are typically in narrow gauge; these lines utilize separate sheds and vehicles and are not joined to the intercity railway network, and some also regularly carry passengers. Some light rail and tramways are on a 3 ft 6 in gauge, including the system in Kien-k'ang and Tor.

Railways within coal mines and quarries typically operate under even more restrictive gauges, of which 2 ft (610 mm), 1 ft 11 1⁄2 in (597 mm), and 1 ft 8 in (508 mm) are attested in Themiclesia. These gauges are also not unknown to other applications in salt mining, agriculture, and gardens. Certain passenger railway operations, typically converted from industrial railway, also possess tracks in these gauges, though in recent years many of them have been regauged to more permissive dimensions.

Loading gauges

Old gauge

Prior to 1891, there was no standard loading gauge; the gauge on each private railway was decided by the narrowest point on its route. However, for goods wagons, it was commonly accepted that a normal width which would pass through most lines was 9 ft. The expansion of railways, however, encouraged proprietors to unify gauges across their entire network, so that a single wagon could run without the need to unload and reload. The old gauge was formalized only after the new gauge (below) became standard in the 1890s and was defined by a 9 ft (274 cm) and 12 ft 6 in (381 cm) envelope; while few lines were built to these restrictive dimensions, they were chosen for their universality applicability. Many branch lines may accommodate 9 ft 6 in or even 10 ft 2 in vehicles, though deficiencies in one dimension or another required rolling stock in the old gauge to be used in these lines. It is still seen on some branch lines currently, though periodic efforts have been made to upgrade them to the new gauge.

New gauge

When the Central Junction Railway was built, half of which was underground, dimensions of 10 ft 6 in (320 cm) wide by 14 ft 6 in (442 cm) tall were specified to accommodate the largest coaches then in use. This decision was meant to encourage railways to connect services through the Central Junction, which both provided the government a fee and reduced wagon traffic in Kien-k'ang, a major source of complaints. Between 1897 and 1910, most main lines owned by both National & Maritime and Themiclesian & Northwest were converted to the new gauge, while new constructions met the then-named Central Junction gauge. Because the continuous vaults of the underground sections are directly imprinted onto the limits of this gauge, it is also called the "tunnel gauge".

Though generous by 1890s standards, the 7-mile Central Junction tunnel under Kien-k'ang would by 1920 become the most restrictive point on the Inland Main Line, and widening or heightening the tunnel would entail rebuilding it and demolishing everything built above it. Railway engineers noticed that the immovable height limit could be circumvented if traffic were diverted through the suburbs, where trains ran above ground and were subject to fewer height restrictions. Such a practice led to the development of the over-tall gauge, which was seen on railways that passed through the sparsely-populated east.

New-new gauge

The new-new gauge is the electrified version of the new gauge and includes a modest 6-inch increase in vertical height, which enables double-decker trains to have better headroom. Restrictive height barriers were typically negotiated by lowering the track bed in the late 70s.

Over-tall gauge

The over-tall gauge originated in the 1920s after efforts were made to divert freight traffic from termini in major cities, as freight could travel more efficiently avoiding busy areas that are also more likely to have permanent structures that restrict gauge. Benefiting from benign geography, several lines were converted to accommodate boxcars as much as 16 ft 6 in (503 cm) by 11 ft 6 in (351 cm), whose heavier weight in turn encouraged larger and more powerful locomotives. Some of the largest locomotives ever in service in Themiclesia were built specifically for lines in this gauge. Some efforts were made to expand these railways for wartime requirements during the Pan-Septentrion War, which saw a further 6 in added to the width of the gauge. Despite this, the over-tall gauge is not widespread in Themiclesia, and some were (effectively) converted back to new gauge in the 70s by way of electrification.

Non-electrified lines in this gauge are mainly found in the Themiclesian east, where lines are generally single-track and have few factors which impose restrictions, like bridges and tunnels; on these lines, where services are less frequent, the ability to carry more goods per train was at a premium. After the 1970s, the excess height on the over-tall gauge permitted oversized rolling stock that catered to tourism that was booming in the east, formerly dominated by mining and forestry sectors.

Electric gauge

The electric gauge was developed jointly with Dayashina for high-speed passenger service. In the early 60s, Themiclesia proposed using its existing over-tall gauge to serve as the standard for a high-speed service, but Dayashinese engineers believed that those dimensions were too wide and not sufficiently tall to accommodate overhead catenaries that would be required to supply electricity. The modern electric gauge was thus settled to be 14 ft 9 in (4,500 mm) tall and 11 ft 2 in (3,400 mm) wide. This gauge is current on all high-speed electrified lines operated by National Rail under the brand name Themiclesian High Speed Rail.

Railway links to adjacent countries

Nukkumaa

Themiclesia is connected to Nukkumaa by at four operational railways, three of which are located in the western part of the country, and one in the far east. All four railways were built during the 19th century. One railway connected Themiclesia to Nukkumaa, Suurlaakso, and Uusimaa, where an ocean liner to Hallia was the principal means of communication between the Hemithean and Casaterran continents, and the three other railways principally served freight transport to various parts of the Hallian Commonwealth. However, there is a break of gauge at the Nukko border because the Hallian gauge, which is used in that country, does not conform to the standard gauge. Passengers typically transloaded onto Hallian rolling stock at the city of Skengrak, 9 km south of the border with Nukkumaa.

Dzhungestan

The first rail link between Themiclesia and Dzhungestan was constructed between 1937 and 1939 by Menghean forces to strengthen its logistics in the Themiclesian theatre during the Pan-Septentrion War. The line was constructed using forced labour from prisoners-of-war captured in Maverica and Innominada. This railway was later controlled by Hallian forces operating out of Themiclesia and served a similar function in the subsequent invasion of Menghe via Dzhungestan, and under this administration its capacity was enlarged significantly. At end of the war, the portion of the line within Themiclesia was ceded to that country. This railway remains operational as a freight and passenger railway to a number of small towns in the Themiclesian desert but terminates in Sn′ênk and no longer extends into Dzhungestan. A memorial has been erected in Sn′ênk in memory of the prisoners who died building this railway.

In the 2010s, the Trans-Hemithea High-Speed Railway was planned to link Dayashina, Menghe, Dzhungestan, Themiclesia, and Nukkumaa. This development was envisioned as an econmical alternative to air travel and freight that is faster than ocean transport between the states, which takes a less direct route. In design it is capable of a top speed of 300 km/h. The THHSR network is jointly operated by all parties involved and has been considered a remarkable success in political terms. It has uniform signal systems and track and loading gauge, this being enabled by congruences between the high-speed railways of Dayashina, Menghe, and Themiclesia, and dedicated customs offices permit non-stop service between origin and destination.

Maverica

Themiclesia is connected to Maverica by the Trans-Hemithean Railway, which opened in 1952 and connected further to Menghe. This line was forced to close down in 1959 in view of disquiet in Maverica that eventually led to the establishment of a Communist administration in 1960. Themiclesia removed railway infrastructure over several kilometer for fear of its utility to a hypothetical Maverican invasion. This line was reopened tentatively for freight transport in the late 80s, though trains were unable to pass without stops at the border.

Travelling direction

Most Themiclesian railway lines distinguish between "hither" (各, karāks) and "thither" (戉, mngwāts) travelling directions, which are usually equivalent to "up" and "down" trains on some other networks. During the era of private railroading, this terminology was usually applied relative to the locomotive's depot, such that journeys from the depot would be followed by the opposite journey back towards the depot. After consolidation, which permitted locomotives and trains to be maintained or assembled at more than one place, this distinction evolved to reflect the place of the railroad's headquarters, where travel towards it was considered hither. For National & Maritime, trains travelling towards Kien-k'ang were hither trains, while for Themiclesian Northwestern, those bound for Rak were hither. Currently, trains bound for Kien-k'ang are considered hither by National Rail, while those travelling away from it are thither.

Railways which are not on the inter-city network are more idiosyncratic in their nomenclature. Trains on forest and mine railways are often distinguished between trains into or out of the forest or mine.

Passenger service

Rolling stock

Modern passenger carriages in Themiclesia are required to adhere to government regulation, some of which meaning to enhance passenger safety in the event of a derailment or collision. They are required to have a solid vestibule or another feature that reduces the likelihood of telescoping and continuous breaks that can be controlled by the engineer. Breaks must also be fail-safe, meaning that they default to an applied position when decoupled from a compressor.

The first passenger train in Themiclesia, serving the route between Sngrak and Ped from 1836, offered only one class of service to the public—third class—but provided superior accommodations for the directors of the railway. From the 1840s, a three-class system modelled after Casaterran railways was introduced, though first-class carriages were few and far between because most of high society travelled by private coach more than railway. Third-class coaches typically were open wagons fitted with benches, while second-class ones possessed glazed windows and upholstered seats. Early coaches were laid out in an open style, but soon compartment coaches became the norm under Anglian influence. Two-axle coaches were universal until bogie coaches, which permitted easier turning, appeared around 1850.

In 1868, the Railways Act mandated that all rolling stock meant for passengers must be roofed. In 1870, a new style of carriage called the "drawing room" or "saloon" was popularized by Lower Themiclesian Coach Works. It was laid out and upholstered as the eponymous rooms in mansions of the day and attracted travelling elites who preferred its atmosphere to that of enclosed compartments. The drawing room displaced first-class compartment coaches and remains the dominant seating style in this class of service today.

Fares classes and ticketing

For most of the 19th century, stations were given a pre-determined quota of tickets from that station to each destination on the route/network. As the operator could not track the occupancy of each seat on the train between every call (there were typically dozens on longer routes), it was not possible to ensure a seat for a passenger on the entire journey; on busy sections of the railway trains could be oversold considerably, while the opposite was also possible at other places. The general response was to add unscheduled services for the benefit of passengers unwilling to accept a standing journey. Assigned seating was available in a sleeper service, in which a single bed was sold only once; other logistical elements of sleeper trains (e.g. bedding and meals) rendered it the only practical option, while the lack of a bed on a sleeper train was obviously unacceptable.

The advent of daytime express trains after 1877 seems to have encouraged assigned seating, while the telegraph made real-time bookings possible. With only a few stops, it was practical to record the occupancy of each seat between every call of the serivce. In 1878 or 1880, the Central Railway started offering seat assignments on its premier express services, for a reservation surcharge. Initially, only first/second class seats could be reserved, but third class reservations began in 1890; under the surcharge, travelling third costed more than second by unreserved services. The reservation process was time-consuming and labour intensive since the Central Ticketing Office has to keep and clear the ledger for specific services. The CTO could assign a single seat or require the passenger to change seats mid-journey. Nevertheless, by 1895, seat reservation was standard across operators for select services; the general term for them was "reserved service" (對號車, tups-huqs-kla).

"Limited" (特快) trains appeared around 1895, which further preferred speed by means of enhanced engines, unemcumbered schedules, and even fewer calls; a "limited" service was, at the time, often used to denote a better schedule as compared to a competing service. The exact meaning of "limited" was not always consistent. When the railway market consolidated in the early 1900s, "limited" services became established across railways as indicating the combination of the best engines and schedules. Since a limited service by definition has fewer stops than other express trains, seat reservation naturally carried over to limited trains, which consisted of first and second class only. Whether limited or not, such trains were called the "reserved services".

Third-class limited services

Nevertheless, the public operator National Railways started experimenting with a limited third-class service in the 1920s. This shift could be attributed to the deteriorating standards of ordinary express trains at that time; the term "express" was used nearly indiscriminately by both National and T&S, with call schedules similar to stopping trains, to make their services appear more attractive and simply to charge a higher fare. These services often ran at red-eye times to avoid competing with more expensive trains, but commercially they were a success. These services were simply called "limited services", to avoid emphasizing the "third-class" connotation; rolling stock for these services were spartan and singularly prioritized capacity.

Limited third-class stock in the 1930s often had 125, 135, or even 140 seats per coach, and this prodigious quantity disincentivized the offering of a seat reservation option, which was still done by hand. There was also a market segmentation issue, with a consensus that seat reservation should be offered only for the more expensive services.

Computerization

National Rail computerized its seat reservation system between 1954 and 1956, immensely enhancing the efficiency seat reservation. It was now practical to reserve seats for all services, but the railway post-PSW intended to encourage all long-distance travellers to pay an express fares; one measure to discourage travelling long-distance in non-express trains was the refusal to provide seat assignment, threatening to make a long journey unpleasant. With dieselization in progress by 1950, diesel adhesion proved more capable than steam to handle longer trains at higher speeds, whereas a steam locomotive could achieve even higher speeds though at the cost of low adhesive power. Thus, the railway in the 1950s was both more capable of offering capacity on express services and more desirous to do so.

Freight service

Subways and light rail transit

Inter-city network

| Line | Hither end | Thither end | Length | Electrified | Cities served en route | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Metric (km) | Imperial | |||||

| Inland Main Line | Tsin | Rak | 406.3 | 251 mi 73 ch | Yes | Sin |

| Central Line | Tsin | Tenibh | 797.1 | 494 mi 27 ch | No | Lrêng, Ploi, Sn′i |

| Northwest Main Line | Tsin | T′ub | 526.7 | 326 mi 45 ch | Yes | Kengrakw, Mgraq |

| Skngrak Line | Tsin | Skngrak | 833.6 | 516 mi 77 ch | From Ped | Mgraq, Ped, L′in |

| Coastal Main Line | Tsin | Skngrak | 1109.8 | 688 mi 2 ch | No | Ngang, R′ad, Dzep |

| West Main Line | Rim | De | 784.8 | 486 mi 42 ch | To Ped | Tor, Ngang, Ped, De |

| Tor Line | Tsin | Tor | 235.6 | 146 mi 10 ch | No | |

| Prjin Main Line | Tsin | Qe-pa | 702.9 | 435 mi 70 ch | To Qe-pa | Rim, Te, Qe-pa |

| Eastern Line | Nek | Rak | 503.2 | 312 mi | No | K′an |

| P′an Line | Tsin | P′an | 1423.6 | 882 mi 55 ch | No | |

| Southeast Line | Rim | Stseng | 808.9 | 501 mi 43 ch | No | Stui, Nek |

| South Loop | Tsin | Nedrings | 514.6 | 319 mi 12 ch | No | Nek, Gob-kri |

| South Main Line | Tsin | Ngwang-tu | 362.0 | 224 mi 35 ch | Yes | Stui |

| North Transverse Line | Rak | Skngrak | 692.5 | 429 mi 21 ch | Yes | Sn′i, T′ub, L′in |

| T′ub Line | Rak | De | 434.6 | 269 mi 45 ch | No | Sn′i, Rap, T′ub |

| Central Transverse Line | Rak | Ngang | 449.9 | 278 mi 79 ch | Yes | Ploi, Mgraq |

| Qong Main Line | Rak | Qong | 218.8 | 135 mi 47 ch | Yes | |

| Tenibh Line | Rak | Skngrak | 693.2 | 429 mi 69 ch | No | Tenibh, Pê |

| Riparian Line | Rak | Kengrakw | 278.0 | 172 mi 30 ch | No | Lrêng |

| Sin Line | Sin | Lreng | 102.1 | 63 mi 26 ch | Yes | |

| Kengrakw Line | Kengrakw | Ploi | 113.6 | 70 mi 33 ch | Yes | |

| West Isthmus Line | Qe-pa | Sam | 494.4 | 306 mi 39 ch | No | |

| East Isthmus Line | Te | Belong | 307.3 | 190 mi 47 ch | No | |

| L′in Main Line | Rim | Mek | 793.5 | 491 mi 77 ch | No | Loi, Ngang, Tats, Ped, Hrip, De, Pê |

| Prabay Line | Qong | Prabay | 773.5 | 479 mi 45 ch | No | |

| Great Eastern Line | Rak | Sakarna | 2235.8 | 1386 mi 17 ch | To ′An | ′An |

| Great Northern Line | Qong | Tiba | 2336.5 | 1448 mi 43 ch | No | ′An, Apollonia |

| Ka-ra Line | Apollonia | Ka-ra | 303.9 | 188 mi 31 ch | No | |

| Southwest Line | Tsin | Nedrings | 281.8 | 174 mi 51 ch | No | Prit |

| Trans-Hemithean Railway | Rim | Doi | 341.1 | 211 mi 44 ch | No | Nedrings, Ngwang-tu |

| Total | 19518.6 | 12102 mi | ||||