Themiclesian Navy

| Themiclesian Navy | |

|---|---|

| 航 (gang, lit. "fleet") | |

War jack of the Themiclesian Navy | |

| Founded | 17 February 762 |

| Country | Themiclesia |

| Branch | Navy |

| Size | 41672 active 24233 reserve |

| Part of | Ministry of Defence (尚書國防部) Navy Department (航曹) |

| Headquarters | Tonning, Brjêng-nêng |

| Colors | Aqua |

| March | the navy don't march |

| Engagements | |

| Commanders | |

| Secretary of State for Defence | Njik L'in-ljang |

| Chief of the Naval Staff | Krang′ ′seng |

| Admiral-in-Chief | Mjen Koh-ring |

The Themiclesian Navy (震旦航, tjins-dans-gang), or officially the Navy (航, gang) is Themiclesia's military force responsible for operations at sea and in certain terrestrial areas. It is headed by the Department of the Navy, an office of the Ministry of Defence. The Navy possesses numerous corvettes, destroyers, and other marine and freshwater vessels. It traces its origins to the early 9th century and has a central place in the defence of Themiclesia, as well as the protection of her interests abroad.

Definitions and structure

Statutorily, there is no single organization called "the navy"; rather, it is an umbrella term of several organizations that, for historical and operational reasons, have shared a close relationship or leadership. Themiclesia's constitution does not permit military organizations to exist independently or to claim direct allegiance to the sovereign. All military organizations are nominally part of some civilian administration, led by civilian administrators that can answer to parliament, directly (for ministers) or indirectly (for civil servants, via the Council of Correspondence). This ensures unitary governance, and there is thus no possibility of any legitimate military action against the civil administration. The navy's officers, like all military officers, had been civil administrators, and non-officer complements are subjects in service to the state as embodied by civilian administrators. Though this paradigm has been steadily waning since the middle of the 16th century, parliament only changed the legal status of the navy's officers between 1881 and 1934. The civilian "shell" of Themiclesian armed forces has no discernable function today, but budgets are still passed in terms of civil administration, and the Admiralty remains, on a legal level, civilian advisory staff to the Director of Fleets, which today is a sinecure. The following are the civilian administrations under which the navy exists:

- Bureau of Fleets (航令, gang-mlingh) — the Consolidated Fleet's and the Inland Fleet's assets and their operations. The Great Admiralty (航中記室), technically a staff office to the Director of Fleets, is in charge of operations by Consolidated Fleet; the Director of Fleets is constitutionally a subordinate of the Privy Treasurer, though the latter official in modern centuries plays no role touching the navy. The Bureau of Fleets is the default administration into which new naval organizations are classified, such as the Department of Naval Aviation (航空).

- Bureau of Naval Engineers (海寺工令, hme'-lje-kong-mlingh) — Naval Procurement Service and several institutions relating to research and development

- Bureau of Passengers (冗人令, njung-njing-mlingh) — traditionally, roles that cannot be filled with impressed sailors (e.g. financial, clerical, legal, medical) and are not related to construction or manufacture are classified into the Bureau of Passengers; it is also responsible for certain instances of impressment and the Themiclesian Marine Corps

- Bureau of Ports and Passes (關津令, kwran-tsjin-mlingh) — Management of revenues arising from leases and other sources

- Bureau Impressment (海官令, hme'-kwal-mlingh) — Levying sailors from merchant fleets, recruitment of professional sailors, and the sailor schools

- Bureau of West Woods (西章令, ser-tjang-mlingh) — Levying shipwrights for shipbuilding, their compensation and access to state forests

History

Pre-modern history

The naval history of Themiclesia can be traced to the 2nd and 3rd centuries, when settlers in what is now central Themiclesia began to expand outwards, ousting native societies that inhabited the surrounding regions. On land, the Tsjins state employed cavalry and chariotry to great effect, but in what is today Gwje'-ding, the aboriginals have mastered the use of canoes and harrassed Themiclesian troops that could not fight on water. A similar but direr situation existed in the southwest, where the Prjin-aboriginals exploited the Inland Sea to great effect, emerging from the coast and launching attacks on settlers without warning. An advantage that such aboriginals held was mobility and security from assault if retreated to deeper parts of the water. These factors conditioned the creation of ship-based forced to tackle such resistance. In 321, the "navy" department (水兵曹, sljui-prjang-dzaw) was created in the Ministry of War. Like the cavalry department, it was a locale-specific branch, recruiting only in prefectures where it was necessary to field ships; it manufactured, and sometimes commandeered, vessels and trained its soldiers separately from the other branches. The organizational successor of this navy was the Themiclesian Army's Lake Fleet, which was transferred to the Navy in the 19th century.

The ancestor of the Navy was established only later, tied to Themiclesia's foreign policy objectives. Even though hostilities sometimes broke out in early history between the emerging Themiclesian state and various Columbian native societies, it is ultimately the need to suppress piracy and protect merchant interests that backed the navies' existence. Themiclesia imported materials such as jewels, furs, wooden containers, and pigments from the Columbian natives and exported fabrics, porcelains, and other crafts to them. A source of coastal disorder that proved persistent was Maverican pirates, who looted the coastal settlements and raided merchant fleets. Seafaring Columbian natives also, at times, posed threats to Themiclesian merchant vessels. A second radix of Themiclesia's naval tradition is occasional naval conflicts with Maverican fleets, the first recorded instance of which occurred in 491.

Initially, warships were converted from merchant ships and escorted them across the Halu'an Sea and later to Meridia. The warships were manned by guilds of merchants in Themiclesia, providing the warships' complements; after the 5th century, the state appointed superintendants to oversee their activities, but ties with merchant fleets remained close. By the 8th century, maritime trade had grown in volume such that escorting specific merchant fleets became unfeasible; instead, the government took over the naval operation and launched regular circuits of warships along the coast of the Halu'an, the Columbian coast, and the northern coast of Meridia. The organizational link with trading guilds became a financial one: Themiclesia used revenues from customs and other levies to fund its navies. In 854, Themiclesia divided its fleet into two circuits, one for the coast of the Halu'an Sea, named the North Sea Fleet (北航, pek-gang), and the other for all other coasts, for the South Sea Fleet (南航, nem-gang). The SSF had its home port first in La Rivera then moved it to Portcullia in 1010.

During the 9th through 14th centuries, the SSF frequently clashed with Rajian raiders; these occurred before the advent of gunpowder. In 1323, the SSF was defeated by the gunpowder-equipped Menghean fleet in the Battle of Portcullia; the new technology was quickly adopted by the SSF and the NSF in but a few years, though with very little consideration over its tactics.

The loss of Portcullia resulted first in a search for an alternative base, then a second clash with the Menghean Yi navy in 1352. Themiclesia made a temporary base, in 1325, on a small island on the coast of today Naseristan. While the use of gunpowder remained largely at the same level, both fleets were better armed, fortified with thickened hulls, and more primed for battle. However, the Mengheans still overcame the Themiclesians after the initial barrage of cannonfire subsided, and both fleets engaged for boarding action. The Menghean fleet's key advantage over the Themiclesian was in strategy. Knowing that the Themiclesian fleet was not fatally hurt by the defeat at Portcullia and will regain its presence, the Menghean commander prepared his fleet for a decisive battle, while his opponent prepared for a long-term voyage along the Meridian coast. The Mengheans adopted a more aggressive fleet formation, able to concentrate diffuse fire more effectively, while the Themiclesians sailed in a school formation. Portcullia and a more constrained mission (up to two months from port) allowed far more fighting men, while the Themiclesians provisioned for up to two years. This resulted in a crushing defeat that sank 114 Themiclesian warships amongst the 150 lost; 17 sailed home. It has been commented that the Menghean fleet behaved as a co-ordinated whole, while the Themiclesian one was merely an aggregation of ships, expecting to engage on that level.

The defeat at Naseristan had profound effects on the Themiclesian Navy and its relationship with society and state. By this point, it had survived the collapse of two dynasties and was regarded as a permanent institution. Maritime historian N. Nielsen believes that "through the shock of Portcullia and Naseristan, the Themiclesian Navy was weaned off its merchant roots and came to accept that its future business will not be the suppression of pirates and protecting trade, but manifestation of its country's military power, just like the army, but on water". From a financial perspective, further conclusions could be drawn, according to B. Larter, who writes,

[the] Themiclesian navy up to Naseristan has a strong fiscal basis to justify its existence. By controlling key trading posts, sailing routes, and suppression of pirates, it was able to generate revenue to support the state. This is not to say it was always a net cashflow-positive organization, but its directive was to protect activities that generated revenue. As fierce as pirates at sea and bandits on land may be, the navy never fought an enemy with the backing of state power and resource; that was the realm of diplomacy, at this distance from home. But Menghe's use of its navy as an arm of its war machine, without a clear fiscal incentive, to assert the dominance of one state over another, changes this aforementioned relationship. From Naseristan on, it is not the navy that funds the state, but the state that funds the navy. From Naseristan on, the navy does not protect the commercial traffic and revenue but destroy rivals from adversarial states. From Naseristan on, the navy did not fight for reasons of finance, but reasons of power.

The first major naval conflicts the Themiclesians fought with the assistance of gunpowder were against the Kingdom of Sylva, who first expressed interest in the southern tip of Columbia in the 1400s. The SSF were again defeated in 1482, forcing them to relocated their home port from near San Alvarez to the mouth of the river adjoining La Riviera. Meanwhile, the NSF found it increasingly difficult to ensure peace in the Halu'an Sea due to overland incursion by Rajian settlers, who populated the north of Columbia. In 1607, the SSF were defeated by the Sylvans again. However, given the rise in Columbian population and propensity towards commerce, Themiclesian merchants began to prefer trading at home rather than sailing out to sea; as a result, the navies were both recalled and placed at home in 1610. Both underwent reductions in scale and armaments. In the 1700s, the NSF were charged with protecting coastal waters for the most part, while the SSF participated in enforcement of trade tariffs on the Columbian east coast and minor expeditions in northern Maverica. In 1791, the SSF was burnt to the waterline completely by the Tyrannians and never rebuilt.

Following the SSF's destruction in 1791, the Maritime Company that formed the backbone of the SSF was merged with that of the NSF. The part of the Themiclesian Marine Corps that belonged to the SSF were amalgamated with its counterpart in the NSF in the same process. While the government seriously deliberated the possibility of rebuilding the SSF between 1792–93, its fiscal resources were drawn away to the Army's campaign in north Maverica (then called Njit-nem). Initially (and severely) underestimated, the Maverican campaign dealt a fatal blow to the unreformed Army, ultimately triggering its implosion and the subsequent reform in the 1820s; the campaign was so costly that revenues raised to fund it stifled domestic commerce and the export economy, in turn further causing a number of industries to collapse. This period was called the "years of unprecedented and unfathomable misery for all walks of life" by Tyrannian historian N. M. Hoppers. Yet, as soon as the war ended, reduced taxation and rejuvenated commerce triggered a dramatic (against the backrop of the war) improvement in industiral environment, which the government and public came to associate with disarmament. The SSF's opportunity to be rebuilt thus disappeared in favour of spending on "pursuits of peace and prosperity". The future Themiclesian Navy can therefore be said to built on the foundation of the NSF.

The NSF has historically preferred to establish a wide presence and react to threats with speed. Such an approach contrasted with the SSF's desire to target its foes, even in their moments of strength, and force decisive battles at sea. These two ideologies are attributed to the enemies that both fleets faced: the SSF tended to engage with larger and better-armed fleets from Casaterran states, while the NSF dealt with smaller fleets, often of pirates or minor princes, but at a greater frequency and agility. Agility was required to prevent property loss, since pirates were after goods and sometimes hostages and are more effectually stopped before they reach either. In 1817, the government considered proposals to abolish the navy altogether. Through frantic lobbying, the NSF was able to secure its own existence by pointing to frequent piracy and serving as the country's defence force when the Army was under intensive reform. Further arguments asserted potential naval threats in the future, and the maintenance of a fleet, even in diminished form, as claimed, would make future expansion to address such threats easier. One such potential threat was the Organized States, according to the NSF, even though there was no actual evidence. In 1819, the NSF was renamed the Consolidated Fleet, and in the following year, a new portfolio over domestic and maritime trade was created, including the Consolidated Fleet; a Secretary of State was appointed in 1835 for more extensive government oversight.

The NSF received funding sufficient for the maintenance of their vessels but seldom for the purchase of new ships. This situation changed for the only time between 1852 and 1865, during which a Rajian invasion then Columbian invasion was feared to take place by sea. The NSF purchased several new ships-of-the-line at the beginning of 1853 and coastal ironclads towards the end of this era and into 1860–61. Further coastal ships were purchased between 1862–1864. After the Compromise of Sngrak-tju in 1857, threat of Rajian invasion gradually subsided, leaving a partly-modern fleet. Fears then turned towards an OS invasion, which was deemed existential by some, should the slave-holding side emerge victorious; this fear occasioned the purchase of the ironclad steam ships for coastal defence. Timing of the ship purchases could hardly be less favourable, as wooden ships-of-the-line were quickly phased out during the following decade. Nevertheless, the Navy would continue using these ships well into the 20th century, a situation they could not anticipate. Nevertheless, the Navy continued to press for funding under the dubious pretext of OS aggression, to which the government responded inconsistently. In the aftermath of the great flood of 1894, the government found itself hamstrung for funds and resolved to solve all matters with the OS diplomatically.

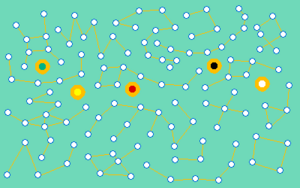

Culture

The current naval jack dates to 1834 and consists of an aqua blue field, charged with a single, white, eight-pointed, hollow star, with four white rays emerging, centred on the centre of the star but not touching it. This flag continues the Navy's tradition of the stellar theme and is generally thought to be a simplification of the previous naval jacks, which were, upon comparison with Casateran examples, thought overly complex and literal. The symbolism of the star or stars is deeply associated with the Themiclesian maritime tradition. As the nation's naval activity predates the introduction of the magnetic compass in the 11th century, celestial navigation (i.e. navigation via the directional significance of stars) was one of the defining arts of an oceanic navy.

Successes with celestial navigation allowed Themiclesia to establish early dominance in the Meridian Ocean and influence polities on a distant continent. Early astronomy was also intertwined with astrology, and naval astronomers held certain celestial phenomena to be portends; while the reading of signs gradually separated from the art of navigation, the navy continued to recognize foretelling power of certain signs. The position and magnitude of Jupiter and Mars, for example, were considered indicative: appearance and enlargement (probably an artifact of marine vapours) of Jupiter, the star of peace, was deemed favourable, while that of Mars, the Star of Warfare, was ominous. It has been questioned by some scholars why a navy should consider signs of war unfavourable, but other researchers state that the signs were read non-specific to the navy. That is, a bad sign was always a bad sign, regardless of the reader. The star on the current jack is believed to be Jupiter, enlarged and with a hollow centre, the most favourable configuration. The old jack (used up to 1722) contains the five (ancient) planets in rough alignment, said to have been observed on the eve of the greatest naval victory in history; the sign was thought to herald "a sagacious reign and world peace and plenty". The other stars represented asterisms under which the navy has achieved major victories. This jack was called the "Great Banner of Victory", as it documents major victories.

Salute

The use of the modern military salute can be dated in the Navy to the end of the middle ages in Casaterra. The precise date of its introduction is unknown, but it was in common use in the 1400s, possibly through contact with Hallia or other Casaterran powers. According to graphical and written sources, the Casaterran salute may have originated as an alterative to the Maverican hand-over-heart sign that Themiclesians adopted at the start of the Common Era. In social situations, both hands would be clasped together and placed over centre of one's chest, indicating intentful and respectful listening. Additionally, the head may be bowed, and eyes closed. It is assumed that, in the navy, this gesture would have been used by sailors whenever their superiors were speaking to them, as over large distances on the open seas it could be difficult to tell if an individual was paying attention or not. Gradually, it is thought, this may have evolved into a single hand over the heart, so that the other hand could continue holding something, or that dirt on one hand would not soil the other. Contact with Casaterrans would have brought the salute (consisting of one hand doing a visor-raising action) as a visible, one-handed gesture that may have somehow been conflated with the hand-over-heart gesture. There is some evidence showing that Themiclesian sailors may have stayed in a salute for as long as they are spoken to, supporting the conflation theory of introduction.

Whatever be the original use of the salute, it seems by 1500 the salute was used as a form of greeting between equals. It did not become acceptable to salute superiors until much later; sailors still bowed to their captains in the 1800s and particularly to admirals, who were deemed partly civilian administrators. Observing the situation in the Themiclesian Marines, who were first organized as a standing military unit in 1318, it is quite possible that sailors also did not distinguish between left and right hands in saluting. The naval practice of left-handed salutes is traditionally explained as a vestige of the knightly greeting, where the hand more distant from the other knight would be used to push the visor up; in turn, this is because if both knights used the hand closer to each other, their raised hands might collide or obscure eye contact with each other. However, some scholars object because there is no record of any marines (or indeed any naval officer) being on horseback or using helmets with visors, where this inconvenience may have been relevant. Other Themiclesian militaries are of no assistance in deciphering this practice, since the salute did not spared to the army until well into the 19th century. It is notable that the navy did not salute the naval jack, using it strictly as an interpersonal gesture. An admiralty order in 1901 permitted saluting as a legal greeting to any superior naval officer who was not an admiral, and it seems by this point the left-handed salute was out of fashion in the navy.