Ambystoma arenos

| Lapenter's Axolotl | |

|---|---|

| |

| Ambystoma arenos | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia

|

| Phylum: | Chordata

|

| Class: | Amphibia

|

| Order: | Caudata

|

| Family: | Ambystomatidae

|

| Genus: | Ambystoma

|

| Species: | A. arenos

|

| Binomial name | |

| Ambystoma arenos De la Bordez, 1942

| |

| |

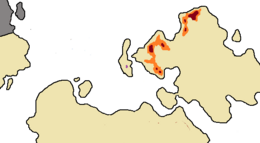

| Range of A. arenos in Inyursta. Dark red represents known extant range. Orange represents historic (extirpated) range. Purple represents extant range of disputed or uncertain origins (Meridian Ponds). | |

Ambystoma arenos, commonly named as the Lapenter's Axolotl, but also sometimes refered to as the Sandridge Axolotl, and Pésacoja de Sable; is a species of salamander endemic to shallow, sandy ponds in northern Inyursta.

Physical Description

Lapenter's Axolotl is a smaller-sized species of mostly aquatic salamander. Only slightly larger than the closely related sister-species Ambystoma bardus, but still considerably smaller in both average mass and head size than most "axolotls" found in La Ameripacha Libre.

Holotype

Holotype = Adult male specimen: Aquatic morph. 17.9cm TL, 9.8cm SVL, collected in the outskirts of Sant Francine by Lapenter in 1936. Described and published by Rodrigo de la Bordez in 1942.

Ecology

Habitat & Distribution

The species is restricted entirely to the Subtropical Sandy Uplands of Inyursta; though inhabits all three subsystems, including the Sierra Grande Sand Escarpment, the Sante Françine Massíf, and the Isla Orteja Central Ridge. The origins population in the Isla Orteja Central Ridge, at site known as Meridian Ponds, is disputed.

A. arenos inhabits clear-water, mid-to-high pH level, sandy-bottom ponds with emergent grasses or soft herbaceous vegetation. Madisòn et al. (2017) determined that the "partial hydroperoid" is the most important predictator of A. arenos occupancy - wherein ponds which retain a fully-submerged section through the dry season yet experience dry-down of the edges and shallow sections are optimal. Such ponds provide a refuge for aquatic adult occupancy and developing larvae; yet allow abiotic factors such as fire and wind to expose sand around the edges and burn back emergent woody vegetation and palm encroachment. This leaves a grassy, sandy-bottomed shallow when the wet season rains raise the water level. Ponds which hold water but dry down often loose edge habitat important for breeding due to emergent vegetation and siltification; meanwhile, ponds that don't hold water do not allow aquatic adult occupancy and may trap and kill undeveloped larvae.

Life Cycle Ecology

Eggs are laid attached to stable vegetation in the pond, usually grasses but sometimes Echinodorus. Within 2-4 weeks, depending on sun exposure, the eggs hatch and larvae emerge. Early stage larvae are reliant mostly on fairy shrimp, water fleas and other small macroinvertebrates. As the larvae grow, they begin to eat more worms and larvae from summer-breeding insects, and "fall ins" (insects or invertebrates which fall into the pond and are unable to escape). Adults display a similar diet, but also eat frog tadpoles and in some cases display cannibalism towards their own young.

In uncommon circumstances, some larvae, usually due to encroaching dry downs, undergo metamorphosis and become terrestrial adults, which bury into the wet sand and await the rainy season. Others in ponds which hold water all year round, direct develop into aquatic adults.

The life expectancy of an aquatic adult is 5-7 years, while the life expectancy of a terrestrial adult is only 2-4 years. Because of this, aquatic adults are more necessary for population resiliency and longevity; however, terrestrial adults allow for improved gene flow and occupancy of new ponds.

Population Dynamics

LaChiffre & Guyero (2020) defined a healthy population as "over 50 unique adult individuals, with at least 45-45 of those adults being aquatic individuals". According to this assessment, only 6 extant wetlands (representing a total of 18 ponds) hold healthy populations.

Conservation

The conversation of Lapenter's Axolotl is currently a subject of intense effort and interest to the scientific community. While it is not the most imperiled species of animal in Inyursta, or even amphibian

Threats

When asked what the most pressing threat to the future of Lapenter's Axolotl, species expert Louísa LaChiffre replied "what isn't a threat to this species?"

Habitat loss, through fire suppression, timber silviculture, and physical development of habitat account for the majority of wetlands considered "lost". Natural wildfires are needed to keep vegetation from encroaching on the shoreline, as well as to keep sandy soils sandy and stop the build up of litter and organic sediment. Timber silviculture has seen massive tracts of formerly subtropical scrub, pine savanna and grassland habitats converted into plantations of row-planted lumber pine, paper pine, and fire-starter palmwood. One historic breeding site outside of Sant Françine, where a wetlands scientist in 1979 recorded over 110 aquatic adults and 40 terrestrial adults in a single night (while surveying aquatic vegetation communities), is now a shopping mall and residential suburb with only small, heavily vegetated and shaded wetlands left stagnant inbetween the development.

Invasive species pose another threat to the future of A. arenos. Species include the larger and more aggressive Common axolotl (A. cuscatlanum) which eats both larvae and adults of this species, introduced and escaped game fish which enter wetlands and predate on this species, and invasive plants which alter the ecology of wetlands.

Amphibian diseases such as XXX and XXX are also responsible for declines in numbers of healthy adults; and climate abnormalities have been implicated in several "missed" breeding years.

Poaching is considered a minor, though present threat. In 2014, self-proclaimed "wildlife wrangler" Thómas Cruthez was arrested for possession of 20 wild-caught Lapenter's Axolotls. Cruthez claimed that we was "trying to help save the species" and that "why is it legal for the zoo to do it but not me!?!". Cruthez later admitted that the salamanders were taken as larvae from Meridian Ponds, and was subsequently fined but not imprisoned, and the salamanders released back into the wild.

Conservation Actions

A. arenos is listed as Class II Amenazadenté. Collection, possession or harassment of the species without a permit is illegal. Destruction or severe modification of existing habitat is currently prohibited - however critics argue that existing protections do not cover upland spaces between wetlands and leave the species vulnerable to continued fragmentation.

A coalition of zoos, aquariums, private, provincial and federal partners have come together to support a thriving captive headstart and release program. Late-stage juveniles raised in captivity have been released at 5 different sites, in conjunction with habitat management efforts to restore pre-industrial fire ecology and wetland hydrology to the sites.