Antargat

| Part of a series on |

| Satyism |

|---|

Template:KylarisRecognitionArticle

Antargat (Bhumi: अन्तर्गत), also called the Inner Truth, is one of the sects of Satyism influenced by Yanogu thought and folklore. It was developed principally by the 17th Prior of the Kwelacchin Monastery, Alim of the Stones. Alim revealed to his followers that there is a cycle of violence which traps all beings in our level of reality, escape and ascension comes from avoiding the two great evils: shame (लज्जा, lajja), which is what causes individuals to accept and seek out violence upon themselves; and pride (अभिमान, abhimana), which is what drives individuals to commit violence on others. Between pride and shame is humility (विनय, vinay), which is the supreme virtue of Antargat Satyism and allows all beings to avoid violence as victim and perpetrator. Vinay can be achieved in one of two ways; through living a life completely free of violence, or by expelling violence in life with rituals and humble acts. The life completely free of violence is very rare and provides that spirit with a divine-like status, according to Antargat philosophy, only seven people have ever achieved this status. Most of Antargat thought is devoted to the rituals and behaviors that cleanse the spirit of violence.

Antargat is limited almost entirely to the monasteries of the Koh Valley and surrounding area, although it shares many elements with other Satyist schools of thought.

Antargat has historically been mistranslated as "Antherghast" and it is still occasionally called the Ghost Flower sect.

Beliefs

The central belief in Antargat is that all actions have lajja (shame), abhimana (pride), or rarely vinay (neutral). Because of this, most spirits also have an aspect that is primarily shameful or proud. Shameful actions are those that accept or invite violence--thieves and lawbreakers invite violence as do those who insult others or drink to excess--and also actions that permit violence to be done, Antargat promotes the duty to retreat. Prideful actions are the commission of violence on other beings, physically striking someone or hurting them, but pride also includes coercive actions such as threats. Vinay exists for all things, including spirits. Whenever someone reduces the vinay of a spirit by harming their shrine, for example, which is what holds them aloft in higher realms, the spirit is given the power to restore their vinay in the physical world, typically by harming the perpetrator of the original harm. Many spirits exist and there are rituals to protect people who accidentally violate a spirit's vinay. There are three principles that Antargat rituals follow:

- Balance (तुलयति, tulayati) is the principle that two opposite actions weigh against each other to cancel one another out. The two things that are weighed against each other are pride and shame. Pride is balanced out by shame; therefore the prideful should be shamed. Likewise, shame is balanced out by pride; therefore the humiliated should be exalted. In practical terms, this means that the perpetrators of violence should have violence done to them and the victims of violence should do violence to others. Almost all Antargat rituals seek to fulfill the need to balance through symbolism and divine power.

- Non-violence (अहिंसा, ahiṃsa) is the opposite of prideful violence. It is often what should be a shameful act, but instead of being bad and reducing the spirit's vinay, it increases it by balancing prideful violence. This can take the form of symbolic or real mortification of the flesh, acts of blind obedience, or rarely a violent act made under orders instead of selfish impulse.

- Counter-violence (विरोधी, virodhi) is the opposite of shame. Virodhi is often a violent act, but it is not prideful because it cancels out shame and increases vinay. When a person is the victim of violence and they defend themselves, for example, their act of counter-violence cancels out their shame. Rituals associated with virodhi can take the form of mortification of others, service in the military or law enforcement, and plant or rarely animal sacrifice.

Many rituals are based on the principle of ipso facto, the concept that one wrong action merits the same action. In Antargat, this is expanded into tathyadvara (तथ्यद्वारा) which is theoretical list of all possible actions and reactions. It was said that Alim alone could comprehend all of the tathyadvara, but many monks and scholars after Alim have constructed their own partial lists that are used in lieu of Alim's prophetic grasp of the spiritual cosmos.

Ganayati

Ganayati (गणयति) means to reckon and in Antargat it is the process of self-evaluation and the more formal evaluation by a monk. Alim believed that all people could evaluate their vinay intrinsically simply through focusing on themselves, but also that people could forget how to do this. He was especially critical of soldiers, who he did not view as inherently evil, but were especially prone to forgetfulness. To cure forgetfulness, Alim demanded a period of quiescence and introspection, essentially joining a monastic order. This concept of the warrior-monk was heavily influenced by the Phuli Empire. Later monks would develop new techniques to aid in the recollection of conscience and incorporate that into the canon of ritual. Different lay people would also help to fill this role in specific communities beyond the monastic world. Yaji women, the Sacetak , and the infamous Pardoners are figures in Antargat society who "remind" people of their vinay when they have forgotten.

Memorization and memory have a sacred role in Antargat for this reason. A person with a good memory is considered especially blessed and those who lack this trait are often considered fundamentally flawed. There are many mnemonic devices--including songs and poems--that contain elements of Antargat theology and convey the long rituals and the essential tathya dvaara lists that maintain balance between actions. There is a social value to being able to recite different tathya dvaara and recitation features strongly in Antargat education and festivals. At many festivals, there is a recitation (in Bhumi) of one or more tathya dvaara and being selected to recite is a minor honor. Those with excellent recollection are given the responsibility of ganayati in daily life and it is expected that those who lack good recollection defer to those who possess it.

Uccatara

Uccatara are the seven semi-divine humans who have achieved a life of complete non-violence without relying on tulayati or balancing actions. Three of the Uccatara are figures of Yanogu mythology--Manas, Semetei, and Seitek--who ruled without ever personally being violent, they are considered models for leadership and good rulers. Three of the Uccatara lived their entire lives in complete isolation--their life stories were revealed to Alim through his contact with spirits. The last Uccatara was Alim's own student, Kasan, who was struck on the head as a middle aged man. Kasan went into a comma and was eventually revived, but never regained his memories or all of his faculties. He eventually died from the wound, but in the brief period in which he was "reborn" and died, his life was completely free of violence.

Pnuematology

Spirits play a prominent role in both the superstitions of lay people and in the activities of the clergy. For the monastic community, the spirits are a source of supernatural research--they use mind-altering substances and other techniques to journey into the higher and lower realms of existence. For the uninitiated, the can provide wisdom and aid in times of need. They are also very powerful and upsetting their vinay can bring ruin on a household. Many spirits are, or were, humans at some point and have transcended or descended through the infinite layers of reality. These spirits are almost always bringers of wisdom; their unique perspectives on life are very valuable and can only be gained through their cycles of life and death. Sometimes, spirits that remain on the human realm have some duty that they must fulfill or wrong that they must avenge. These creatures are often devious and dangerous and should be avoided. Spirits can also be created through extraordinary actions that greatly change the vinay of a place or object. Battlefields between unequal opponents are haunted, not by the spirits of the dead, but by the enormous weight of abhimana that was created. Likewise, sites visited by Alim and other Uccatara are sometimes inhabited by spirits of great humility whose presence washes away shame and crushes wrongdoers.

Beyond the human realm there are higher and lower places inhabited by strange spirits who are only known because of the spirits of dead humans who have ascended and later descended again. These creatures have a powerful kind of vinay that, on the human level of existence, asserts itself like a force of nature. Alim described them as trees with roots that creep into the human world. Cutting a root off to eat or out of spite, according to Alim, may seem to destroy the creature itself from the perspective of the worms, but ultimately the roots will grow back, and those foolish enough to be standing in its way will be crushed.

Most spirits have an intimate relationship with places and objects--pools of water or protruding boulders for example--that exert force on them. Like gravity, they are drawn to the place that their spirit's roots are in, even if they can wander. Spirits are also bound by an analogous relationship to things that are related to their homes. For example, spirits tied to a particular stone are tied, in a lesser extent, to other stones. This concept is explored by Alim's successors in discussions of magic and ritual called the sabda ke anusara (शब्द के अनुसार), often abbreviated as "Sakanu".

Cosmology

The Antargat concept of the universe is infinite and ultimately only the regions of the universe in the immediate vicinity to humanity are useful or possible to understand. Central to the human experience is the planet and the rest of the universe is therefore measurable in degrees of separation from humanity. Humans can perceive three levels of existence higher and lower. After death, human spirits will sometimes ascend and descend these levels in a never ending journey; their ability to perceive higher and lower realms are increased as they move away from the planetary level. Spirits are classified by their direction of travel--either ascending (चढ़ाएं, chadhaen) or descending (उत्तरति, uttarati)--which is determined by their vinay. Alim described the entire universe as an endless pool filled with souls, every soul having a different weight and size sinks, rises, or floats. The weight of every soul, according to Alim was determined by vinay.

Practices

There are three primary types of rituals in Antargat based on their objective: rituals to increase vinay and decrease pride or shame; rituals to "hone" vinay, to perfect balance between pride and shame; and rituals to communicate with higher realms. The first type of ritual is also the most common and were originally established by Alim of the Stones in his poetry collection Taş Balansı. Many rituals are designed to remove violence from life without inflicting violence on someone else, which Antargat philosophers theorized was the default and natural reaction to violence.

Orto Orto

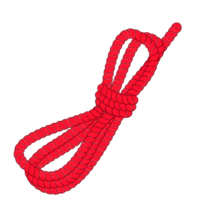

Many rituals are small, daily activities to improve the spirit such as referring to others using an honorific (master or mistress) to reduce pride or using a diminutive to reduce shame. These kinds of activities are called "Orto Orto" (ओर्तो ओर्तो) or the "middle middle" way, and are considered some of the most virtuous behaviors since they are both humble acts and acts of humility. Rituals in this category include leaving flowers or other gifts at a shrine, washing someone else's hair, striking a monk (ritually) with a "whip" made of colorful yarn, kneeling on someone's back, and serving someone else food (especially a social inferior).

Juyoodoun

Juyoodoun (ञुयोओदोन्) means "to strike down" and refers to the everyday things that rid the soul of shame. It is also called the wrestler's method (kuroshchu jolu, कुरोस्ह्छु जोलु). The original and essential act of Juyoodoun is to strike back at an attacker. In this scenario, which was originally described by Alim and recorded by his student Bakytbek, the attacker has incurred abhimana and the victim has incurred lajja. The simplest way for both people to eliminate their vice is for them to literally exchange places. Alim demonstrated this in a wrestling match with Bakytbek, which is called the Betmeteb (बेत्मेतेब्, a play on the phrase betme bet). While in Antargat philosophy, there is always a duty to retreat, to avoid violence at all, self defense and even offense as a defense, are accepted elements of life. The Betmeteb has had a strong influence on traditional wrestling, which is practiced by monks and lay people as a sport and to celebrate certain holidays.

Bakytbek is the primary source for Juyoodoun and wrote book of the same name which describes the many ways he discovered to reduce lajja. He begins with a discussion of lajja, which he described as a sickness of the soul brought about through physical trauma. He compares it to a cut in the skin which becomes infected when untreated, eventually manifesting itself again as violence in the physical world. Bakytbek described three primary rituals that eliminate lajja through the "Wrestler's Method".

Suture is the metaphorical process of sewing closed an open wound. It applies to most cases of violence, which is when a struggle is over and so neither retreat nor self defense are options. This practice also applies to many kinds of nonviolent disagreements, which Bakytbek considered pseudo-violence and a breeding ground for evil. Because it always after the fact, Bakytbek encourages everyone to seek restitution when possible since that will undo the wound. When this is not possible, someone burdened with lajja should take a long piece of yarn or rope and tie it into knots. Once finished, the rope should be taken to a monk, who will bless it and make it into kamchy (कम्छ्य्). If the supplicant knows the person who gave them lajja, then the monk will take the kamchy to their house and leave it on their doorstep. The kamchy should then be used by the attacker on their own back, the attacker should then spill a drop of their own blood on the kamchy and give it back to the monk. Instead of using blood, the attacker can also make a new kamchy from red yarn or rope. If the attacker is not someone that the victim knows, the monk serves as surrogate and the supplicant pays the monk for their time.

The entire kamchy ritual, being complex and sometimes expensive, is seldom used. Most people instead use kyska tuyun, which is the tying of ritual knots. Different knots have emerged over time for different affronts like bruises, broken bones, harsh words, and more recently bad driving. Many Antargat households have a large spool of rope dedicated to kyska tuyun. Kyska tuyun are often kept by the maker, but can be given to an offending party as an insult. The kyska tuyun can also be bought in stores (typically shelved around greeting cards) or from monks and given to enemies. Kyska tuyun is considered an acceptable substitute for kamchy, but the official statement on which should be used says "better one kamchy than fifty kyska tuyun", which indicates that it is not suitable to waste too much time tying knots. Malcontents in a community are often called knot-tiers for this reason.

When Antargat adherents musk seek a greater virodhi than can be supplied by a kamchy ritual, such as the murder of a family member, they wear an enlarged kyska tuyun on their clothes to indicate their desire for restitution. During the Norzin Empire, Antargat men who served in the military all wore a kyska tuyun, a sign that they were not violent and prideful, but seeking balance and virtue through their service. This has become both a part of Yanogu folklore, in which heroes wear knots for fallen brothers or fathers, and also part of military uniforms in Kumuso.

Embrocation is comparable to the application of balm or a salve to a wound. Embrocation is called for when there is no other party responsible for lajja; this is the case when someone is the victim of an accident, their attacked is dead, or they have been attacked by a spiritual power. Libation (kuyuu, कुयुउ) is the traditional method; pouring out an offering of milk at a shrine is a formal expression, but mostly it comes in the form of spilling a little water or tea when given a drink. In addition to kuyuu, it is also common to use a literal balm in a ritual called jayyuu (जय्य्लुउ). The two main types of balm are lemon and onion infused, although there are many others. When using balm religiously, it is first applied to the skin (more area for more lajja) and then a small amount of the same balm is left on a cloth outside. The underlying concept is that a bad spirit cannot tell the difference between the person and the leftover balm because they smell the same.

Jayyuu has spawned the more common tradition of keeping small towels at the door so that a guest, when leaving, can wipe their hands on the towel. This cleans off any lajja that a guest may have accidentally picked up in the house, but does not correct purposeful wrongdoing by a host. Special towels called door cloths, commonly made from felt with the image of a bird on them, are kept for this purpose. The term door cloth also applies to the more ornate, embroidered towels that are used at the hot-springs and in monasteries. These are considered especially lucky and going to a spring for spiritual cleansing is partly attributed to this tradition. It is typically enough just to rub the cloth slightly between two fingers as a polite gesture; more aggressive gestures such as wiping the hands or arms signals that the host has given insult in some way.

Cauterization is the process of burning a wound to prevent bleeding and infection and it has a similar meaning in Antargat. It is essentially the process of accepting violence, rather than seeking restitution, and inflicting virodhi on oneself. This considered the least favorable option and the Monk Bakytbek says that it should be used only when the pain of righteous virodhi on another outweighs the cost of not achieving full vinay. This kind of ritual is therefore limited to instances in which it would be inappropriate to seek virodhi, such as when the lajja originates from a close family member, a monk, or a public official. In traditional and mythic stories, this involved jvalati (ज्वलति), physical burning. Depending on the story, often a husband who loves his wife too much to hit her, the supplicant would walk over hot coals with their bare feet, hold their hands into the fire, or brand themselves with the name of the offending party. The Monk Bakytbek, however, calls this kind of behavior full of prideful exhibitionism, and instead suggests pouring hot wax from a blessed candle on the skin or touching a brand to a hidden part of the body.

Even Bakytbek's recommendations are too extreme for most circumstances and so there is a separate set of rituals called "raksa" (रक्षा) or "the ashes". There are the greater and lesser raksa rituals. The Greater Ritual is the burning of a part of the self, but not the self. This includes burning a lock of hair and fingernail clippings--excreta is not acceptable--and has given rise to the collection of fingernail clippings in raksa jars. Raksa jars are colorful clay pots decorated with scenes from Yanogu mythology that contain nail clippings or hair. At the end of the year, if the owner makes it through the year without needing to perform the greater raksa, they join in a special celebration called dhumena (धूमेन) in which their jars are "donated" to a community bonfire. The bonfire, made with gharuwood, is quenched in scented water creating a pleasant smelling haze. For longer festivals, this is supplemented with incense torches to extend the effect. The Lesser ritual reverses the relationship and instead of making an offering to the fire, the supplicant takes an offering from the fire to carry with them. This can take the form of throwing or smearing ashes on the head and face for a day-long ritual; the ash is then washed away at the end of the day. The more extensive version of this is to take a partially charred piece of wood and carry it around or wear it as an ornament until the practitioner forgets the affront (or until they feel satisfied with the ritual) and then the rest of the ornament is thrown into the fire, occasionally at dhumena.

Yaji women (यजि) are special members of the community who wear the Raksa trinkets for a group of people, council people with grudges, and keep an account of the internal troubles of the community. There are very few Yaji women now, but they were once important people who could be consulted about marriages and business arrangements by warning people of grudges that they could not learn of otherwise. Yaji women were supposed to absorb the ill-will that comes naturally in close communities and, after entrusting a grudge to a Yaji women, it was supposed to never be spoken of directly again. This role helped to diffuse tensions by helping people avoid each other and stop the spread of rumors. She could also serve as an impromptu interpreter of tradition by telling people when their complaints were too petty to be carried around, helping to distinguish personal dislike for real insults. Yaji women are distinguished by their large necklaces composed of many tabs of wood.

Baktuluu soodager

Baktuluu soodager (बक्त्ıलुउ सोओदगेर्) means "happy merchant" and stands for the Negotiation Method, a book by the Monk Evaz on how to rid the soul of abhimana. In comparison to the Wrestler's Method (Juyoodoun), which essentially requires that attackers submit to the restorative actions of their victims, baktuluu soodager is from the perspective of the attacker. The Monk Evaz wrote the book because he believed that victims do not and cannot always seek the restitution of Betmeteb (striking back), which leaves the attackers with a debt of abhimana that poisons their souls. Evaz was especially concerned with the fate of murderers, whose victims were beyond reach by normal means. The Negotiation Method is composed of the Three Humiliations: Taman (तमन्); Orozo (ओरोशो); and Tazaloo (तशलोओ). These rituals are based on a parable Alim told called the parable of the homicide winch a man kills his brother and is burdened with guilt and self-hatred. In the parable, the murderer tries to pretend that his brother's body is still alive by walking around supporting the body; when this fails, the murderer tries to feed his brother rich foods and wine. Eventually, the murderer accepts his evil act, washes the body, and buries him. The Three Humiliations are based on the levels of this parable.

2. जोगोत्मोक् (Blood)

3. ओल्तुरुउ (Death)

Taman is the first humiliation, the Humiliation of the Feet, and is supposed to refer the Parable of the Homicide in which a murderer wishes that his victim was still able to walk. In Taman it is essential that the supplicant is at foot level and, in it's most literal interpretation, the supplicant prostrates himself at the entrance to his home or a shrine and visitors step over the supplicant to enter and exit. Other interpretations require visitors to actually step on the back of the prostrated supplicant. For Taman there are three levels of severity; the first being described above. The second and third are required respectively for the drawing of blood and an actual killing. When blood is drawn by an attack, the attacker should subject themselves to ridicule of being naked at the temple and, instead of being walked over or stepped on, the supplicant is kicked. It is preferable to suffer the indignity of being kicked at the door, because otherwise the monks are called on to scourge them. If someone commits murder, they are supposed to have boiling blood or water poured over them, especially their feet. The scalding prevents them from walking, so they will depend on someone else to drag them around in a special harness provided by the temple.

The extremity of these rituals are not suitable for everyday acts of pride like cutting in line or shouting at a shopkeeper, however, and so there are the julangaylak (जुलन्गय्लक्) rituals for smaller offenses. Julangaylak means, and generally is, "barefoot". Walking without shoes is considered a good enough public penance for many infractions, since it is both generally not painful, but signals a need for ahiṃsa to everyone. This has been called "red footing" because those that slaughter animals are typically barefoot. Julangaylak is also the wearing of shame-sandals, which are special sandals made from painted grass that slowly deteriorate as they are are worn. Shame-sandals were popular among the pious aristocracy as an artful expression of humility and became the norm for Yanogu, but even wearing normal sandals is called going barefoot.

Orozo is the Humiliation of Food, a kind of fasting. In this kind of fasting, a supplicant must give away all of their food and may not buy it or eat it unless someone gives it to them. As a result, orozo for most people is also a period of vagrancy since they must collect scraps of food from strangers to survive. Their families are not supposed to feed them, except with scraps on the street; this makes family meals somewhat complicated, so those practicing orozo often sleep outside of the home. This also acts essentially a public referendum on the crime committed since everyone has the ability to withhold food. If the whole community decides to withhold food, then the offending party will die or leave. This is meant to represent the loss of the ability to eat in death as described by Alim.

The lighter and more common version of orozo is just the giving away of food. A supplicant can set up a table outside their home and let people take what they want, they could distribute it themselves to neighbors or the poor, or they can give their food to the local monastic community. A special kind of food called "jerbirnerse" is sometimes made from dried meat, berries, and liquid fat. This can be made as an offering and, more recently, bought in grocery stores. Since the development of refrigeration, there is seldom enough preserved food in a household to adequately meet the standards of orozo.

Tazaloo is the Humiliation of Purification and it means "to clean". The first and most important part of tazaloo is called the "Assumption" (मितअम्दुक्, mitaamduk) which is the responsibility of a murderer for the corpse of their victim(s). The Assumption is its own family of traditional burial practices, which are based on Alim's parable and later works by other monks. The rest of tazaloo is for the remaining spiritual burden after the Assumption or for when the bodies are not available for those rituals. The first steps are to shave the head, to put on funerary clothes, and don a mask. This allows the supplicant to symbolically take the place of their victim in death. They must then wash in a special bath--either one of the monastery baths which are sanctified, or in a bath of milk--and then go to sleep outside, preferably in proximity to the grave of their victim. Preparing oneself in this way allows the spirit of the deceased to take revenge if they desire it and to forgive the offense if not.

Taza tumar are amulets that were traditionally worn by those performing tazaloo so that living people would not mistake them for a revenant or ghost. They were traditionally simply wooden discs with the words "men tirüümün" (literally I am alive) carved into one face. The taza tumar have taken on additional meaning as mementos of lost loved ones. The name of the deceased is carved on the inner face and the traditional phrase on the front, which understandably means that no one is buried with a taza tumar. Because of the prominence of perceived piety of taza tumar; they have also become an ornament unto themselves with different calligraphic portrayals of the phrase in many media present in Yanogu jewelry.

Tar Jol

Tar Jol rituals--the "narrow" rituals--are only practiced by the very pious, such as monks, are should only be undertaken whenever one's spirit is already very clean. These are true neutral acts which are used only to perfect a spirit already very full of vinay. These rituals were not developed by Alim, but by his disciples. There is no compendium of such rituals, although meditation and fasting are both universally acknowledged as legitimate, and they are often prescribed by teachers for their students. Monks often seek actions that are neutral vinay as a kind of spiritual research, constantly evaluating their spirits to see what aspect their actions have. Some famous examples are digging a hole and then filling it back in, carrying water upstream and then dumping it back into the source (this is called saras, सरस), and giving away money collected from gifts (कनक, kanak). These rituals almost always have palindromic names when possible.

Adam Boluu

Adam Boluu, which means "to be human", has to do with spirits in higher realms, since they are often unable to participate in normal rituals. There are rituals seeking aid from a higher spirit--typically giving gifts at a shrine or repeating prayers--and for seeking forgiveness from an irritated spirit. Many are combinations of both, first asking for forgiveness for offences, and then asking for aid. Forgiveness is sought by taking on the negative aspect that has offended the spirit or deity so that they do not have to act. The most common type is called rone (रोने) or "wailing" and is intended to trick a spirit into thinking that the offender has already been punished. For example, in times of sickness, the adults of a community would take to the streets wailing loudly so that the spirit that had brought the disease would think that all of the children had already died.

Organization

Like Most Satyst sects, Antargat exists principally as an association of monasteries and the laypeople who adhere to their published works and teachings. Antargat is one of the smallest sects of Satyism, having only the primary monastery in the Koh Vally in Kumuso and two secondary monasteries in Xiaodong and Tava. The spread of Antargat occurred chiefly under the Norzin Empire, during which Antargat was considered heterodoxy for a time.

The Priory of the Naryn Monastery, as the direct inheritor of Alim's status of supreme teacher, is the nominal head of the organization and presides over almost all inter-monastery functions. The Priory of Nayrn does not, however, have authority over liturgical matters, and his primary function is to redistribute funds gained through pilgrimages to Nayrn to the other two monasteries. Scholarly debate on liturgical and ritual matters takes place in the form of the official Antargat periodical Considerations which is published by a special committee which appoints its own members on the recommendation of the various priors. There are seldom any conclusions to the papers and debates published in Considerations, but best practices emerge over time that are slowly incorporated into the liturgy and ritual of the monasteries.

In a tradition that dates back to the Juqu Commandery, the Nayrn Monastery has received material support from the government of Kumuso in exchange for their services as civil servants and educators. In the 1940s, however, the services traditionally provided by the monastery were moved to a special civilian wing of the monastery. The Zhang Gui Wing of Nayrn monastery is still use as a government office and its workers provide "monastic" services to the government. Although the services provided by the monastery are now performed by laypeople, the monastery receives much more remuneration than is earned by the small office space it provides for "maintaining the cultural presence" of Kumuso.

History

Some of the essential elements of Antargat philosophy and spiritualism are drawn from the belief system of the central Coian steppes generally and the Yanogu people specifically. Certain sites, venerated for the presence of spirits long before the First Phuli Empire, were incorporated into the stories and parables of Alim. Many of his explanations are considered to be miracles by his followers since they were later confirmed by archaeological evidence such a burial grounds and battles sites. This view of history, of revelation through spiritual contact, is an important part of the Antargat view of it's own past.

Kwelacchin Period

Kwelacchin was a monastery built in the early 4th century BCE by the Phuli Empire to administrate it's western border and protect its pasture land in the region from incursions from the Oghuz. During this period, the monastery was part barracks, part government building, and part prayer hall. As keepers of the peace, some of the Phuli monks carried short, knotted whips with them to immediately correct breaches of the religious code of the time. The monks faced several difficulties in their administration of Kumuso including the language barrier with the Oghuz inhabitants and the native religion.

All citizens were forced to convert to Satyism, but few them understood Bhumi, the liturgical language, or the religion as a whole. According to popular tradition, one of the monks, who is called colloquially Father Urka, learned taught children short songs in Bhumi that he explained to them in Yanogu so that they would act correctly around other monks and avoid their liberal dispensation of corporal punishment. Father Urka's songs were essential for the dissemination of the language and culture of Phula and ensured the long-term passivity of the Yanogu.

The Kwelacchin site contained three buildings surrounded by a wooden palisade, sitting on a hill on the southwest side of the city so that the largest of those buildings--which contained a watchtower--could see advancing enemies from the plains. They could also see, generally the layout of the town and the behavior of the inhabitants. On several occasions during the early years of the occupation, the monks foiled rebellions before they formed by watching the streets of the city in the evening and rooting out secret meeting places.

The monastery collected tributes from the use of pasture land in the Koh Valley, taxes from the inhabitants of the town, and were also allowed to keep property seized from would-be rebels. Most of their revenues from these sources were, however, in turn collected by the regional and imperial governments of the Phuli Empire. In order to supplement their income, the monks introduced apiculture to the Yanogu for the first time. Although the Yanogu knew and took advantage of wild honey, the monk's constructed artificial hives which were more efficient and accessible. They traded honey to the townsfolk for grain, cloth, and other necessities. The first locals who were incorporated into the monastic community were workers who learned apiculture and maintained the monk's hives, but lived in the town.

Uluuchig Period

The Uluuchigs were initially opposed to the monks at Kumuso when they took the western slopes from the Phuli. The Uluuchigs ordered the monks to abandon Kwelacchin, but eventually decided not to burn it and instead used it briefly as a military outpost. Several prominent monks were executed, but the majority were merely disarmed and sent away. Eventually, the monks were allowed to return to Kwelacchin to use the apiaries, but were forbidden from living in the monastery since it was considered a fortress. Without their home and policing authority, the monks quickly fell into disarray as many of their order deserted and returned to Phula or joined the tribesmen on the plains. Korkut, the first Uluuchig Bey, greatly restricted the rights of the monks, ordering them not congregate unless for religious services and forbidding them to purchase arms or make arrows.

This period lasted for the priorship of Chubuk from 55-93 CE. Chubuk was never explicitly forbidden from trying to build a new monastery, but any attempt to do so was swiftly stopped by the Bey. Leading up to a directly after Chubuk's death, there was turmoil at the Bey's court as the two latter of Korkut's three successors had extremely short reigns. Ispino became Bey in 95 CE and, instead of continuing the suppression of the monks, enfranchised them again as a policing force. They were allowed to enforce religious law so long as they also protected Ispino from rebellion, either among the people or in his own forces. Ispino enjoyed one of the longest reigns of any Bey, holding power for 36 years until his death of natural causes in 131 CE. Ispino and his three successors, all of whom reigned for over 30 years, are called the Yellow Finger Beys, a reference to Buddha's Hand Fruit, for their reliance on the monks. The monks were not allowed to carry weapons with them, but could generally force citizens to enact their punishments by threatening them with the harsher methods of the Bey's soldiers. The monks were also required not to profess any allegiance to Phula and the Adhikari, which marks the formation of the "Antargat" sect in it's earliest form.

It was during this period that the kamchy emerged, one of the most essential and enduring customs of Antargat.

In 234, Ulan was appointed Bey after his predecessor Bolot died with very little favor in the Uluuchig court. Ulan wanted to eliminate the influence that the monks had on the public after observing their methods, but believed that it would be impossible to order an end to their policing without risking a rebellion from the monks. Ulan gave the monks a site for a new monastery, a gift that immediately endeared him to the Prior Jyral. The townspeople were pleased to see the construction begin since, in addition to the luxury of having a monastery, the monks also dug a well. The new monastery was constructed far from the river and access to a well allowed the construction of new homes around the monastery as well. The modern Avan Quarter is the general area of that expansion.

Pardoners

A divide emerged between monks who were actively in the service of the Bey and the monks who maintained their loyalty to the Adhikari. After Ulan's reformation of the monastery, this divide became even more apparent since there were monks who wanted to continue their policing activities and others who desired a return to traditional Phuli cloister. Both sides were at odds with the Bey until the appointment of Asan as Bey in 254. Asan, who was struggling with the monks in their capacity as part-time police, wanted to raise his own militia to enforce the law. Objections arose from the monks on two points; the Antargat citizens had a different legal canon than the rest of the population and the monks derived a large part of their income from seizing goods from criminals. To solve the first issue, Asan allowed anyone in the city to seek recourse from the monks if their consciences demanded it and gave the monks some small judicial authority subject to his own. Secondly, Asan gave them the right to collect rents on land immediately around the monastery in the Avan Quarter.

A distinct and small group of monks took over the administration of these duties, nicknamed the Pardoners for their ability to commute sentences or replace them with acts of penance. In theory this was supposed to allow the Bey to determine guilt for criminals and then the criminals could opt for a fine paid to the Bey or a scourging by the monks. In practice, the monks forced all of their tenants to always take the option of penance or else face eviction. The Pardoners, in addition to coercing as many people as they could into adhering to the monk's legal code, also operated a protection money scheme in cooperation with the city's militia. The Pardoners pushed the Bey further and further to the periphery of the city's administration until Damir was appointed Bey in 308.

Damir's first step to reasserting the Bey's control over the city was to require that the Pardoners join his court where all of their official actions were required to take place. Their powers were not greatly changed, which avoided the appearance of impropriety on the part of Damir. Damir also purged the city's militia and replaced them with a much smaller group of professional Uluuchig soldiers who served brief tours in Kumuso and were then released back to their tribes. The Pardoners also retained the rents from their land in the city, but the administration was handed over to a group of court intermediaries. Finally, and after all of his other actions, Damir capped the number of monks allowed in the monastery and forbade them from any further building.

Alim of the Stones

Alim was the 17th Prior of Nayrn, appointed in the winter of 348 after the death of Miral. As a child, he saw Damir come to power and witnessed both the height of the Pardoner abuses and later the severity with which the monks were curtailed. Alim lived most of his life in the vicinity of the monastery, his own father joining them after the death of his mother. Alim was essentially a ward of the order for most of his life and, inheriting some of his father's status, he was made a Pardoner when he joined the order in 323. After two years as a Pardoner, Alim resigned his post at the Bey's court, which he viewed as austere and spiritually vacant. He criticized the Pardoners, saying that their pride had muzzled them and that, if they had simply relinquished their status, their authority would have increased dramatically. For this, he was censured and removed from the monastery by the Pardoners. After that, he became a mendicant and traveled away from Kumuso to visit the Uluuchig court and their holy sites.

Alim returned from his travels in 340, when he heard of the death of Damir. At the time, he was at the Uluuchig court, surviving on the charity of Khagan Semyet the Elder and so he learned relatively quickly of Damir's death and traveled with the new Bey, Nurbek, to Kumuso. The Pardoners, as a faction, were essentially extinct by the time and their position in the court, thanks to Damir, was entirely ceremonial. Many of Alim's former opponents in the monastery had been executed and so, in order to gain the favor of Bey Nurbek, Alim was readmitted to the order. Over the next eight years, Alim became the personal tutor of Nurbek and even converted Nurbek to Satyism, somewhat secretly, in 345.

After the death of Miral in 348, the monks elected Alim as their prior, for the first time securing a friendly Bey. Nurbek laid down the foundations for a new, grand monastery and drew up plans for a temple for lay worshipers. Together with Alim, the Bey organized a grand plan for the city, placing shrines at every crossroads and even a school for Bhumi. Nurbek was a superb disciple of Alim, but was not a successful Bey. The Uluuchigs took notice of Nurbek's frantic implementation of Alim's every word and also the mounting expenses incurred for religious purposes. Several successful townsfolk complained to Khagan Semyet the Younger that Nurbek's constant demand for more corvee laborers was beginning to impact the agricultural output of the city. The Khagan was loathe to entertain complaints from the Yanogu, who had never been friends of the Uluuchigs, but in 356, Nurbek embezzled a large quantity of grain intended for tribute and used it to throw a feast for the faithful Satyists of Kumuso. Nurbek was dismissed from his post and replaced by Kuban.

Kuban was selected, in no small part, because he was a spiritual skeptic who had caused trouble for Semyet the Younger by satirizing and harassing the court's religious officials. Kuban was also Damir's second cousin and so he seemed a superb choice to take the unfolding religious revival in hand. Kuban was initially exactly what the Khagan expected; a dispassionate and efficient administrator. As Bey, he again disbanded the monastery and used their building as a storehouse for aging meat, which was a special insult for the mostly vegetarian monks. Kuban seized their apiaries as well, beating those tending the hives along the way. Alim resisted at this point and Kuban had him arrested. There are many apocryphal tales of their exchanges, but it is relatively certain that Kuban converted to Satyism after several days of discussion. With another Satyist Bey, the monks were reinstated and construction projects resumed, albeit at a more sustainable pace than Nurbek had demanded.

After the conversion of Kuban, Alim began to promote a less orthodox theology in Kumuso. It is at this point that many of his most famous parable and sermons emerge and the point at which scholars start to view Antargat as a separate Satyist tradition.

Disciplines

Alim wrote very little himself, believing that spiritual truth can only be communicated from person to person. As a result, most records of Alim are from his immediate followers, especially the small group of individuals that he met at the Uluuchig court. These writers were not welcomed by the monks when Alim returned and took the priory and so much of their own writings have been lost, except for the transcription of Alim's words. One of the most authoritative pieces on Alim's preaching is clearly the preamble to a much longer discussion of theology with the commentary physically ripped off from the bottom. This internal enmity has produced a scarcity of sources, especially sources from those that Alim considered his personal friends. Most of the expansions of Alim's work came from established, senior monks who lived in Kumuso during his exile. The most important of these authors was Bakytbek who wrote several long, thorough examinations of the moral framework that Alim laid out during his lifetime.

Zhang Gui Reforms

Zhang Gui was removed the Tao court in the 9th century CE and, after failing to gain patronage in Xiaodong, accepted an invitation from the Bey of Kumuso to take up residence is a new monastery built for his use. Although he was a social outcast exiled to the distant and poor province of Kumuso, Zhang Gui brought with him some of the concepts of legalism and court life, which he enforced on the monks. He was able to implement his reforms primarily because the Bey built a brand new monastery for him specifically and made that new site the benefice of the state-administered rents. This was to avoid the impression that the Bey was directly attempting to subvert the priory, which would have upset the public. This was part of a larger ploy by the Bey to earn Tao protection from Uluuchig tribute collectors. The plot was famously unsuccessful and resulted in the death and execution of both the Bey and the 26th Prior of Naryn, who supported the Bey, were executed. At this point, Zhang Gui was made the 27th Prior of Naryn, gaining the legitimacy he needed to formalize and structure the religion.

Zhang organized a strict curriculum that had to begin at a very young age; he considered boys who came to him after puberty as essentially unsalvageable intellects. Many of those who were too old were still accepted, but were relegated to an indefinite period of novelty during which they acted as domestic servants for the monks and those who were on track to become full brothers. This division between the higher and lower ordinations allowed Zhang, and all subsequent priors, to keep control of the brotherhood by preventing would-be dissenters from rising through the ranks. The course of education that Zhang insisted all of the monks follow included literacy in Bhumi and Xiaozi. Zhang later also encouraged monks who wanted to be serious scholars to learn Pardaran. Zhang did not approve of xiao'erjing, which was the local script used for commerce, and forbade monks to use it.

Zhang believed that the transcription of books, while it was often necessary, was a waste of time better spent in discussion and in writing new commentary. He had several monks learn the art of engraving so that the most important (and shortest) texts could be preserved in metal sheets and in stone.

Maintaining the apiaries was a favorite pastime of the monks before Zhang became prior and he saw its continuance as a subtle defiance of his wishes. As a result, it was used as a defiance of his wishes and it was in this period that the Pranayama Clique, also called the Bee Society, emerged. The Bee Society was opposed to this formalization of their religion and maintained a parallel record through oral tradition. Later, the Bee Society was reconciled with the Priory and currently they are an informal group that meets periodically to criticize official canons and try to find places for improvement. They are also responsible for the bees themselves, although that work is mostly done by lay volunteers now.

Juqu Beylik

One of the most important roles that the monks could now serve after Zhang Gui was as clerks and record keepers for the state. The Juqu Beylik was a period of harsh repression of the Yanogu, who were seen by the Khaganate as an untrustworthy and rebellious people. The Khagan stopped hearing complaints from the citizens personally and instead entrusted the entire city to the Juqu family. Unlike previous Beyliks, the Juqu were given the city as a heritable holding; the nine Beys from 552 to 763 were all members of this family. While it was a hard time for the native Yanogu, the monks, who were also led by a "foreign" person, were seen as allies by Juqu Shuzi, the first Bey of the period. Shuzi entrusted the education of his children to Zhang, who did not disappoint. The Juqu Beys and their families were all able to write and speak in Xiaodongese, which greatly enriched them as traders and allowed them to build a comprehensive, loyal bureaucracy with the monks.

In return for their services, the monks were provided with a larger benefice and substantial donations from the state. This tradition of cooperation between the monastery and the Bey has continued to this day. Government offices in religious buildings are considered an especially prestigious post in the modern era because of their connection to the Yanogu people and their beliefs.

Togoti Period

Kumusi Flower Period

The Oogids greatly encouraged the formation of the unique aspects of Antargat in order to secure their position as masters of Kumuso.

Pardaran Period

Under the Shahdom of Pardaran, there was a retraction in the resources available to the monks and a conflict arose between them and the new state-sponsored Irfanic temple.

Etrurian Colonization

The Etrurians financed the construction of a church in Kumuso and, initially, was interested in converting the Yanogu.

Post-War Period

Nationalist and anti-colonial forces in Kumuso largely saw Antargat as a return to traditional order after the Etrurian and Pardaran occupations.