Bhaga

| Part of a series on |

| Bhaga |

|---|

|

Bhaga (Bhumi: भग) was the religion of the Boreo-Coians , which promoted a concept of earned immortality through reincarnation, a holy social order enforced by the gods, and the consumption of Myristica mel . This religious system probably emerged during the 18th or 17th centuries BCE as the Boreo-Coian Culture expanded into central and western Coius. There are few contemporary sources on Bhaga; much of its history is drawn from oral traditions recorded by later religious groups and from comparative analysis of religions thought to have descended from Bhaga.

Origins

Bhaga was promoted primarily by a Boreo-Coian nomadic warrior aristocracy which operated along the northern coast of Coius during the Galdian period of Zorasan. These nomadic kings did not form a cohesive state or a comprehensive pantheon, but it seems that many of them enjoyed mutual recognition. Henotheism emerged both as a method of gaining political legitimacy during conquests and as a way of showing respect to allies. Conquered peoples retained their own religious traditions; their gods were adopted into the greater mythos of the expanding Galdian culture. This system was upset during the decline of the Galdians as early Badawiyan civilization expanded into central Coius and displaced both the Galdians and Boreo-Coians. During this upheaval, many of the oldest sites of Boreo-Coian religious traditions were conquered by the Badawiyans. This prompted a bifurcation of the Boreo-Coian pantheon; the gods attached to land lost to the invaders were considered left-handed gods who could not be trusted and brought about suffering. The other gods were considered right-handed gods and protected order and happiness.

As the Boreo-Coians moved away from their ancient homelands, they established two deities who represented the division between the two kinds of spiritual powers. The Divine Twins were brothers who patronized all other gods, each representing half of the spirits of the world. They were not greater than all other deities--though were doubtless enlarged through their preeminent position in the pantheon--but acted as mediators between the two worlds. As the Boreo-Coians expanded, they assigned newfound spirits to one of the twins, after which it became a permanent fixture of that locality. Right-handed gods had to be obeyed and worshiped while left-handed gods had to be appeased and feared. Other than this theological divide, however, many religious observances were the same for both kinds of spirit and both had priests assigned to them.

Right-handed, or Dzathe, gods had a strict social order. This could have emerged because of the many linguistic and cultural traditions that were periodically under the control of Boreo-Coian kingdoms as a way to reconcile many social needs across large amounts of time and space. This also solidified the importance of the ruling class by making them comparable to the Divine Twins.

Left-handed, or Madze, gods had the power to upset social order and often did so when they did not receive adequate attention from the population. A rebellion or a famine was often taken as a sign, not that the people were rebellious, but that a king had failed to mediate with the Madze gods.

Characteristics

Bana

Bana is the principle of realization and means that a fully realized soul can be reincarnated into another life. It is the fundamental objective of Bhaga, although there are other values at play, the underlying purpose of Bhaga is to instruct individuals on how achieve a second life and, though potentially endless repetitions of reincarnation, immortality. The way that a second life is achieved is through piety, which could be accumulated in many ways, but there was no specific level of piety or system for determining ones place in the world. Instead of relying on introspection, practitioners of Bhaga depended on priests to evaluate their souls and direct them towards pious actions or confirm their future rebirth. Bana was something that was mostly accessible to the upper classes of society or auspiciously families with strong connections to their ancestors, but the trappings of Bana influenced every part of society that it came into contact with.

Past lives were as important as potential future lives to Bhaga practitioners, partially because a previous successful incarnation made a future one more likely. Priests could perform certain rituals and tests to ascertain who an individual was in a past life, although this was considered somewhat unreliable and there are many stories of brave young men challenging a priest's interpretation and going on discover their past selves. The art of diving past lives is extremely diverse, but includes such activities as taking a psychoactive substance to contact spirits, extispicy, casting lots, and even such simple things as comparing birth dates to death dates. This was an important rite of passage for young men especially. For the wealthy, if their children were not immediately confirmed to be old souls, they could seek the opinions of many priests in hopes of finding a more auspicious answer, but for most people it was a once-in-a-lifetime opportunity. In some kingdoms, it was a guaranteed right that every youth should be given a divination upon attaining the age of majority.

Puja

Puja is worship or reverence for the gods. In ancient Bhaga societies, this most often meant volunteering time for local religious establishments to assist in rituals or maintenance of their temples. Writings and oral traditions differ on this subject, but generally speaking individual temples had traditions of work ratios which would reward individuals who donated their time or resources to the temple with time spent involved in rituals with the priests. Puja also included participation in public events such as festivals, during which especially exuberant activity could result in rewards from the priests.

Weekly religious services such as modern religions often employ were unknown during this period; the priests instead kept careful track of the phases of the moon and maintained a special series of rituals which had to be completed along the lunar cycle. Participation in rituals depended entirely on the day of the month and there was very little hierarchy of the rituals except for special services for the full moon, which often coincided with festivals and public activities.

Samadhi

Samadhi in a general sense means respect for ones ancestors--remembering family lineages, caring for tombs, and giving offerings--which was distinctly non-ecclesiastical function. Priests themselves, as devotees of the gods, were forbidden from participating in these rituals.

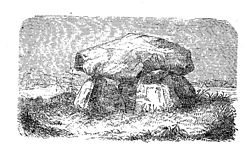

Perhaps the most distinctive trait of Bhaga are the field of dolmen constructed for the purposes of Samadhi. These sites were, much like Bana, restricted primarily to the upper classes, which constructed dolmen to honor their own past lives and the past lives of family members. These constructions were copied by the lower classes when possible, which prompted the wealthy to construct either more numerous or more elaborate buildings from their past lives. Many of them include inscriptions describing exploits of a spiritual ancestor and rarely the physical remains of such a predecessor.

Asvamedha

Asvamedha was a special kind of animal sacrifice which was used to draw the attention of the heavens and the gods as a whole. While smaller sacrifices of other animals or plant might draw the attention of a specific deity, horses were favored and prized by the entire pantheon of gods. Declarations to the heavens were dangerous since not all deities looked kindly upon humans and thus it was reserved for only the most important occasions such the ascension of kings or declarations of war against a powerful rival. Over time, as the resources of kings tended to increase with the population, horse sacrifices were used more regularly. It was considered a great risk to perform the ritual and it was only worth gambling with the gods either when the circumstances were dire or the particular king who ordered the sacrifice felt assured of favor.

Ajanma

The Ajanma were a special class of individuals in Bhaga society who, by virtue of not being delivered vaginally, were considered to be more or less soulless. They could not be reincarnated, at least not in the same way as the rest of society, and could also not have past lives of their own. Cut off from many of the essential elements of Bhaga, they were instead ensured their own separate place. There were strict prohibitions against harming the Ajanma and--when they lacked food, shelter, or other goods--they were assured the physical support of the priesthood. Generally speaking, they were employed as domestic servants or public servants since they were generally considered unsuitable for most kinds of work. They had special codes of conduct which included shaving their heads and practicing sobriety (alcohol being considered good for the soul), but there was no enforcement of these codes, they emerged instead as a way of guaranteeing the benefits of the Ajanma. Ajanma deliveries were recorded by local priests and infants were often given tokens to signify their status, although there was no universal symbol.

The Ajanma signify that Bhaga society had an advanced method of non-vaginal births, likely c-sections, which created this large class of individuals everywhere that the Bhaga priests were present.