Civil vestments of Themiclesia

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

Civil uniforms of Themiclesia have been worn by civil servants and members of certain institutions as symbols of public power and distinction. Lay persons may also wear them in some contexts to express affiliation or support for the state or its institutions.

Audience dress

Audience dress (朝服/受朝服/具服/五重衣), also "taking audience dress", "full dress", and "five-layered dress" is the most formal form of dress the Themiclesian court recognized. As its name suggests, it was used when giving or participating in an audience and consisted of five robes worn on top of each other. The dress code is the same for both the person granting and receiving the audience. The term "full dress" is a co-incident with the Casaterran concept of the same name and was introduced in opposition to an abridged form of dress (below).

The tru-bek consisted of the following garments.

- lreng (裎), the base robe extends to knee/wrist length only and is not visible when fully dressed. This is generally made of a common fabric as it is worn next to the body. The colour is not regulated.

- buk (複), the layered robe ends just above the wearer's feet and will peek out of the layers worn above. This garment is cut much wider than the body of the wearer, the intention being the excess width would wrap around the wearer, providing warmth and ensuring a slim figure that does not disrupt the layers to come above, for which drapery is key.

- qwah (褠), has an oversized cut and is made of fine silk on the obverse and a hard-wearing material on the inverse. Rather than wrapping around the wearer, the robe's excess length forms a train behind the wearer.

- ’unh (褞), has a similarly oversized cut as above and is made of a superior material like brocade and is usually quilted with silk stuffing. Both the interior and exterior of the garment are of silk. The train formed by the ’unh rests on top that formed by the qwah.

- lik (裼), the overcoat that reaches the wearer's knee level and made of a light, semi-transparent material.

Abridged dress

Abridged dress (從省服/旦夕服/三重衣), also "day and night dress" or "three-layered dress". As the name suggested, this attire does away with the ’unh and the qwah that it requires and so the train that forms behind the wearer. The over-robe is directly worn over the buk robe, which is of a separate design and lacks the excess width needed to wrap around the wearer. To compensate for the lost warmth, trousers are worn with the abridged dress instead.

- lreng

- buk

- lik

The accepted rule for using the abridged dress after the 9th century is that officials who meet the sovereign on a daily basis or those meeting each other regularly may wear it.

Colour dress

Colour dress (色衣) was said to have been introduced by Emperor Wŏn of Chŏllo when he was restored in Themiclesia. This idea, though old, has been questioned on account of the well-attested fact that the garment was characteristic the very enemy power, Kim, that had expelled him from his own country. If he did indeed introduce this garment to Themiclesia, it would appear either unmotivated or require the consideration that his court was more influenced by the Kim semi-nomadic culture than he represents. Nevertheless, the colour dress was present in Themiclesia at the latest around 560, as depicted on a funerary mural dating to that year.

The colour dress consisted of knee-length robe with overlapping front panels that fastened along the neckline, which is cut as a round collar. The garment appears to have been cut close to the body as a rule, though roomy examples are known. Sleeves of the robe are usually arm-length. A vest was worn underneath the outer robe, with overlapping front panels forming a V-shape. Layers under the vest consist of any number of robes of variable length. Generally, trousers in the Themiclesian style are worn over the lower body; this would usually mean a pair of close-fitting underpants ending at the calf or ankle and a pair of loose-fitting pants worn over them.

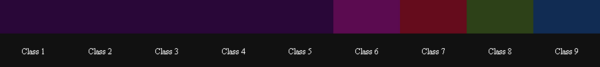

The eponymous colour of the outer garment was regulated by decree, based on the Nine-class System, as follows:

It has been noted that officials of classes 1 through 5 all share a deep purple robe colour with no difference between them. In contrast, colour schemes on homogeneous garments in Menghe and Dayashina do differenetiate higher ranks. Historians understand this to reflect a benign importance of the ranking system in this era, as members of the aristocracy were less dependent on or concerned about rank in the imperial civil service than the standing of their houses. Moreover, senior officials are unlikely to use the colour dress since their positions require them to meet other officials, where the audience or abridged dress would be appropriate.

Generally, fashion on the colour robe is seen in changing length, the size of the sleeves, the diameter and position of the neck opening, and the relative sizes of the upper and lower body. Since the colour of the outer garment is a badge of rank, robes worn as part of official dress always have only one colour; conversely, for private clothing, fancier fabrics are often used by those who can afford to, and patched cloth (with irregularly-placed patches, often intentionally added) was fashionable at multiple points in time.

With an edict of 571, this robe was prescribed for officials "in discharge of duty" (治事) but not giving or receiving audience (朝). This rule would later predispose the colour dress as a primarily military uniform because military officers are consistently discharging their duties (giving commands to their men, etc.) but are not as likely to be giving or receiving audience from another official of similar standing. Conversely, as bureaucratic officials of similar standing are much more likely to meet each other formally during the day, they would use the audience dress more consistently (or the abridged dress).

Despite the above, the difference between the audience and colour uniforms are one of use case, not one between civilian and military officers. If the latter appeared at court or are of a senior enough position they would mostly be working with other officers, they would still be in an andience dress instead; conversely, non-military officials working in remote locations may regularly wear the colour dress.

Sashes

Early system

The sash (綬, dus) is an piece of fabric worn about the waist, originally for the suspension of objects; it was distinct from the belt (帶, dats), whose principal function was to keep robes closed. In Themiclesia, seals were used to close and authenticate letters, and in bureaucratic contexts they became symbols of power. Seals were suspended from the sash, which also gained the meaning of rank and office in the 4th century. In 392, all bureaucrats with a seal of office were required to suspend it from a crimson sash, which was forbidden to commoners; however, a blanket ban on crimson sashes was difficult to enforce, and by the Rang period (early 6th century) the royal court had begun issuing brocade sashes with patterns only known to palace weavers. It is unclear if the colour of the sash was used as a signifier of rank during the Rang dynasty, but it was reformed according to Menghean tastes in the mid-6th century in that way.

Mrangh and Dzei dynasties

Under the Mrangh (543 – 753) and early Dzei dynasties (753 – c. 900), sashes were divided into seven grades:

- Crimson: the emperor, dukes, palatine princes, and their spouses;

- Green: chancellors serving the above;

- Purple: chief barons, barons, baronets, and vice-chancellors;

- Blue: bureaucrats of the 2,000-bushel rank;

- Black: bureaucrats of the 1,000-bushel rank;

- Yellow: bureaucrats of the 800, 700, and 600-bushel ranks;

- Charcoal: all other bureaucrats.

These were awarded according to ranks at court, and it seems they were the only article formally issued by the state. Commoners were not forbidden from wearing sashes of any colour, as long as it was not of brocade. However, the difficulty of harmonizing ranks of the aristocracy with those of the civil service was also evident in sashes, and aristocrats were sometimes assigned sashes according to their own ranks or those of the office they held.

9th century reforms

Owing to the enormous cultural prestige of the Menghean Sunghwa dynasty in power in this time, the later Dzei rulers attempted to incorporate many elements of Sunghwa court life into Themiclesia, ironically with greater effect than Mrangh rulers ever did four centuries ago. This combined with a local maximum of monarchical power that seems to have swept away the final lingering substance of confederacy that had existed in Themiclesia since the 4th century. In this system, the place of the imperial sovereign was greatly emphasized at the expense of other princes and barons.

Sashes, as symbols of courtly rank and power, were overhauled in the reforms of Prince Ruq (帝子鹵) in 847 – 870. Crimson sashes were withdrawn from palatine princes and exclusively assigned to the sovereign; the princes received instead a greenish sash with crimson hatches. Variations in the purple sash of the baronage were introduced to distinguish those who served at the imperial court. On the other hand, the grey sash was generalized to any person who held public office.

Republic to modern day

During the Themiclesian Republic, the system of sashes saw further specification at the higher end, as symbols of individual offices and the social positions they implied. It is thought that the use of reweaving originated in the Republic. After the restoration of the monarchy in 1513, the system of sashes stabilized again, with few revisions until the modern period. Rationalizations accepted during the modern period included the identification of purple as the colour of nobility and of green as that of cancellarial authority. Secondary colours are usually associated with aspects of the rank permitted to wear it.

For example, the Chancellor of Themiclesia was required to wear a solid-green sash, while the First Vice-Chancellor, authorized to act as his deputy, a purple sash with green stripes; the Second Vice-Chancellor, not vested with this authority, wore a purple sash without green stripes. These alterations pushed the system towards specification of individual offices, rather than ranks of them, at the higher end.

| Base colour |

Secondary colours |

Tertiary colours |

Wearer | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nobility | Civil officers | Army (1800s) | Navy (1800s) | |||

| Crimson | Gold, cyan | Purple, blue | Emperor | |||

| Green | Gold, cyan | Purple, blue | Patriarchs | |||

| Green | Purple, blue | Gold, crimson | Chancellor | |||

| Salmon | Gold, cyan | Purple, blue | Crown Prince | |||

| Purple | Scarlet, green | Green, white | First Vice-Chancellor | |||

| Scarlet, white | Green, white | Second Vice-Chancellor | ||||

| Gold | Chief Baron | Account-Chancellor, Exchequer-Chancellor | ||||

| Gold, white | Third Vice-Chancellor | |||||

| White | Baron | President of Barons | Generals | President of Admirals | ||

| Violet | Scarlet, white | White | Baronet | Admirals | ||

| Indigo | Blue, red | White | Attorney-general | |||

| Blue | Blue, red | White | Permanent Secretary | Colonel-general | ||

| Black | Blue, red | Blue | Deputy Secretary | Colonel | ||

| Yellow | Blue | White | Under Secretary, Assistant Secretary | Major | Captain | |

| Aqua | White | Yellow | Other senior civil officers | Captain | Lieutenant | |

Colour robe

The "colour robe" (色褒, sngrek-puks) is an informal but regulated garment of a solid colour that reflected the wearer's rank. In the nine-class system that Emperor Wŏn of Chŏllo introduced after his restoration, officials in classes 1st through 5th all used dark purple robes, 6th a lighter purple, 7th crimson, 8th green, and 9th blue.

This ordering of colours would be an interesting argument on the wearing of coloured over-robes at the Rang royal court, where state officials wore a uniform black colour, while royal favourites, aristocrats, and military officers (those holding no regular office) wore reds and purples.

It is conventionally seen to have been introduced by Emperor Wŏn of Chŏllo in at an uncertain year after his restoration in Themiclesia. Though it is uncertain how this garment originated, it seems to have military connotations, since the earliest individuals instructed to wear it were the troops that he brought to Themiclesia.

The garment consisted of round-collar robe, a cross-collar sleeveless robe, and any number of under-robes of either design. The outer robe bore the correct colour of the wearer's rank. This cutting was unknown to Themiclesia (at least as official garb) at the time of the restoration.

Hats

Like many other Meng people, Themiclesians of all sexes did not usually cut their hear but tied it together in various ways, usually on top or the side of their heads. While the reluctance to cut hair was philosophized as respect for the physical form created by one's parents, scholars generally think this was not the original motivation. In the bronze age, pictorial evidence shows that those with means often tied their hair against decorative hair pins, loops, or both. More head jewellery was worn about one's hair, and in some cases rigid support structures were necessary to prevent increasing elaborate head jewellery, often made of heavy jade beads and tubes, from sliding off. Later, these pieces became standard for wear at court.

Accessories

Modern court dress

Until 1975, Themiclesian nationals appearing at the royal court were required to be in court dress, when the Progressives abolished these rules believing they impeded the public from court ceremonies.

Casaterran forms of dress were accepted for nationals in 1827, traditionally attributed to the trend-setting sartorial flare of the Lord of Ran. The government revised attire rules aiming both to align the Themiclesian court with Casaterran ones and to preserve native affinity. New rules were promulgated by the Cabinet Office in 1841, 1850, 1871, and 1922, by which point it was no longer strictly enforced. After Emperor Hên' came to the throne, his regent Empress Dowager Gwidh forbade further changes to the court attire. While Gwidh died in 1955, subsequent prime ministers were eager to use the antiquated courtly attire to appease traditionalists even pushing progressive agenda. Though now it is no longer necessary to adhere to sartorial rules visiting the royal court, many voluntarily do so, and attire is commercially offered for hire.

Men

In 1827, it was ordered courtiers might wear Casaterran clothes if they also wore a traditional outer-robe (表, prjaw) over them. While Casaterran clothes were much lighter and more mobile than traditional robes, adopters were few and far-between, since courtiers had servants to carry their trains and assist them up carriages and steps; however, amongst the royal retainers, adoption was more enthusiastic. This hybrid attire became mainstream in the 1830s as more households in Kien-k'ang started wearing Western attire. In 1841, Emperor Ng'jarh also permitted courtiers to eschew the outer-robe in non-ceremonial occasions, where badges of rank and honour were not requisite.

While it was not so regulated, formal attire was always worn where full court dress was traditional, which meant a top hat, black tailcoat, and white waistcoat, shirt, cravat, and trousers. Conflict between traditional and Casaterran formality was fortuitously averted since formal Themiclesian activities occurred in the morning, while formal Casaterran occasions, after dark. Additionally, the wearing of a Themiclesian robe over formal Casaterran garments gave the impression that the domestic formality was superior to the introduced one.

In 1850, the forms and occasions of Western dress were reformed at court to meet contemporary Casaterran standards. Men were permitted to wear black or near-black tailcoats for all occasions that formerly demanded full-dress robes and frock coats for other activities at court. It seems for solemn occasions, the traditional robes were still more popular, at least earlier in the reign of Emperor Tjang (1857 – 64). The 1850s saw the tailcoat phased out for day wear in Casaterra, but it was retained in this context as late as 1871 in Themiclesia. That year, the court adopted the frock coat for all daytime activities and reserved the tailcoat for evenings; correspondingly, this was also when state banquets shifted from breakfasts to dinners.

In the 1860s, black became the dominant colour of both tail and frock coats, and waistcoats shed their ornamentation for a more reserved aesthetic, under the influence of Tyrannian Queen Catherine's court. It became awkward for military officers to wear colourful insignia on their tail and frock coats, outdressing government ministers and the sovereign; as a result, military coats also darkened and lost their embellishments. By 1870, military dress coats differed from civilian coats only in cut and buttoning, the former usually double-breasted and closed.

The frock coat remained the morning court dress for the remainder of the 19th century and the 20th. During the 19th, frock coats were informally mandatory at meetings of the House of Commons, since the legislature was technically meeting under royal command and exercising royal powers, but peers sitting in the House of Lords wore tailcoats as late as 1870, since it was felt to be in the immediate presence of the throne, even if unoccupied.[1] This rule also applied to visitors to the royal court. Depending on the occasion, informal or formal frock coats may be worn; formal frock coats were in navy, charcoal, or black and was paired with a waistcoat and cravat of muted colours, and informal frock coats were all the others. Lounge suits and smoking jackets were considered inappropriate.

See also

Notes

- ↑ There was a throne in the House of Lords, but it was usually unoccupied. Some monarchs regularly listened to its proceedings from the throne, and most visited periodically to give royal assent.