Exchequer District Railway

| File:EDR-logo-1.fw.png EDR logo (1969 – 1998) | |

| |

| Overview | |

|---|---|

| Native name | 內吏鐵, nup-req-qlik |

| Owner | Crown corporation |

| Area served | Inner Region |

| Transit type | Suburban rail Commuter rail |

| Number of lines | 7 dedicated 5 shared |

| Number of stations | 283 |

| Daily ridership | 2,130,000 |

| Headquarters | Yellow House |

| Operation | |

| Began operation | 1969 |

| Headway | 8 – 10 minutes (peak) 15 – 30 minutes (off peak) |

| Technical | |

| System length | 595 mi (958 km) |

| Track gauge | 1,435 mm (4 ft 8 1⁄2 in) standard gauge |

| Average speed | 60 mph (97 km/h) |

| Top speed | 100 mph (160 km/h) |

The Exchequer District Railway or Exchequer Province and District Railway (Shinasthana: 內史眔徹鄕鐵, nūp-req-kreps-qāng-qlik; abbr. EDR) is a network offering suburban train services around Kien-k'ang, the capital city of Themiclesia.

The suburban branch lines of the two national railways, National Rail and Themiclesian & Northwest, form the foundation of EDR's network. Suburban services were offered by both railroads since the late 19th century but became increasingly unprofitable while demand only increased. Their suburban networks were purchased by the Crown in 1967, and services since were operated by the Inner Region Transit Board under the new brand of EDR. Three new lines have since been added, and improvements to capacity and accessibility have been implemented.

The urban terminus of most EDR services is the Twa-ts'uk-men Station. There are multiple stations allowing transfer to National Rail and Kien-k'ang Rapid Transit. The EDR also operates commuter trains on the main-line network.

Name

The EDR was registered as the Exchequer Province and District Railway in 1964, noting primarily the extent of its services. The Exchequer Province is the provincial territory surrounding Kien-k'ang, while District refers to the city's own districts.

History

Early commuter trains

The history of suburban lines around Kien-k'ang can be traced to when its first railway line opened in 1849; an extension of the main line opened at the same time to the suburb of Qlang-qrum, though this place has since been consumed by the city's expansion. In the first railway boom of the 1850s, branch lines sprawled from main-line termini to nearby towns, expecting both to deliver goods and compete with stagecoaches running to the city. For railroads, branches were critical to increasing the usage of the main lines by bringing goods to the terminus, though passenger service was also a source of revenues.

As branch lines multiplied, a commuting lifestyle developed around the towns they served and the capital city. By 1900, there were five termini and 30 railway lines crossing Kien-k'ang, including two elevated and one underground lines later forming part of the Kien-k'ang Rapid Transit network. At the same time, the inter-city railways agglomerated into two large networks, the government-owned National Railways, and the private Themiclesian & Great Northwest Railways. Both offered services from the capital city and between them provided commuter services on over 20 branch lines that diverged from the main lines at various points. This system survived T&GN's sale of its network to the government to become an independent operator in 1948.

Post-war

The road network still in its infancy, the post-war economic boom placed unprecedented demands on the country's rail network, and lines around the capital city became particularly congested with both freight and passenger trains. The increase in commuter traffic partly owes to the policy encouraging suburbanization, which the government pursued after 1945 to reduce residential density in parts of the city infamous for crime and disease. Expectedly, new communities appeared in suburbs already well-served by railways, boosting their passenger volume and necessitating increases in services. However, because branch lines converge with main lines to reach the urban terminus, they compete with inter-city trains in shared lines and encumbered scheduling.

In 1953, T&GN rebranded its commuter trains as "Regional Express", which became controversial as the trains, stopping at every station, were hardly express, and this tactic National Rail soon emulated, calling its commuter trains "City Express". These rebrandings were in no small part efforts to beautify the outdated, cramped rolling stock that both operators employed on suburban services. National Rail regularly used coaches built for the army in wartime—these had so few amenities that even brief journeys were barely tolerable.

The terminal shared by both operators at Twa-ts'uk-men Station was experiencing traffic five times its expected capacity by 1959, much of it from morning and evening rush hour trains arriving from the suburbs every few minutes. The unsafe conditions in rush hour was tragically brought to public attention by passengers crowded off the platforms and killed by trains.

Thought the station had 20 tracks, it could not cope with both commuter and inter-city traffic. To relieve main lines and the terminus, it was planned to restructure the suburban network so as to permit commuter trains to travel independently of the main lines and release passengers at several separate stations in the city, instead of a single terminus. At these stations, it was expected that commuters would avail themselves of the rapid transit and bus services. Thus, according to Ecole, "the new routes in the city were planned to be dependent on the rapid-transit network, a progressive insight of transit integration on the part of the planners."

Various realizations of the scheme were tabled before the City in the late 50s and early 60s, but all of them implied that many new tunnels were to be built if widespread demolition in the urban core was to be avoided. With the city under pressure from the central government to extend the highway network and widen roads, the plan did not receive the city's sanction until 1963. During the 60s, the operators looked to other commuter networks and adopted the double decker train as a solution to line capacity problems: that is, if they could not feasibly run more trains, each train must carry more passengers. These trains, however, were restricted by the loading guage of the Central Junction Railway, the 7-mile underground tunnel that led to the terminus. With a height of 14 ft 6 in (4.42 m), double-decker trains were quite cramped, each level being only 5 ft 10 in (1.78 m) in height.

Planning and building

As an entity, the EDR was proposed by both National Rail and T&GN at a time when both were seeking to simply their portfolios and reduce network length faced with competition from road voyage. From them, the new entity would both take over the maintenance and operation of the commuter network, which was less profitable than freight and inter-city service, and free main lines from commuter services, which enabled them to increase freight and inter-city services. Both companies were thus willing to underwrite some of the scheme's cost, given at $190 million in 1965. Much of this went towards new tunnels under the urban core, as the city was then determined to prevent the building of overhead railways, which "caused a permanent overcast on many streets".

EDR planners required a height of 16 ft 6 in (5.03 m) throughout its network to accommodate more commodious double-decker trains. Such dimensions contributed to the project's burgeoning costs, though the added capacity per train and scheduling headroom was warmly received by the city, which shared the belief that room for further increases in frequency was necessary in anticipation of future demands. A dedicated set of stations, within the urban centre and well-connected to the metro network, were planned to enable passengers to alight more quickly and at more convenient points, rather than the older main line stations, particularly at Twa-ts′uk-men, whose platforms were narrow and obstructed with structural columns.

The concept underpinning the EDR was to funnel commuter services approaching the city from similar directions into several quadruplexed "underground corridors", while leaving most of the suburban track work unaltered. The competing concept of digging a network of tunnels under the city-centre had less appeal because more physical stations were thus needed, and they could not all be integrated effectively with the KRT network; route rights would also cost more. Initially, there were to be two such corridors intersecting at Twa-ts'uk-men Station, and each corridor also had several "urban stations" that were connected to multiple KRT lines. The east-west corridor was 7 km long, of which 4 km was deep-level; the north-south corridor was 11 km long, of which 3 km was deep-level. Both corridors, in the deep-level sections, consisted of two tunnels, each containing two tracks. The bore of each tunnel was to be 35 foot. Owing to expense, the tunnels were to be completed one after another, and services would shift from main-line tracks to the new tracks as the latter became available.

The first corridor to enter construction was called Corridor 1, which moved roughly in an east-west direction, parallel to the Central Junction. This line was planned and built at the same time and by the same builder as the HSR tunnel, which for the maintenance of track geometry was tunnelled for 9 km around Kien-k'ang. The join construction required a larger outlay but was preferred because other underground facilities like water and electrical mains were diverted only once to make way for the track work, and because the two sets of tunnels would not conflict with each other.

Opening

Construction work on the new tracks and tunnel work began in 1963, and the first tunnel of the first corridor was complete in 1968. Under Twa-ts'uk-men Station a new bank of five platforms, with ten tracks amongst them, appeared under the main-line platforms. Other stations were built at a shallower depth, though modifications to the rapid-transit stations were found necessary to enable convenient transfers; these included more waiting room and, in some places, increases in service frequencies.

At official launch on July 1, 1969, the EDR announced, not without controversy, that it would replace the names of the branch lines with numbered trains. It was hoped that the renaming and new rolling stock would create the impression that the EDR was a new service, rather than a continuation of the older suburban services. The launch also included new operating patterns, initially connecting the Krat line with the Mits line, which would allow trains to serve both commuters alighting at the city and travellers going across the city. These operational changes led to considerable and maligned confusion, though a publicity campaign mollified public opinion somewhat.

Network expansion

The EDR assembled the branch lines it inherited into four numbered routes (№s 1 – 4) by the time their tunnels were completed in 1980. Between 1969 and 1980, the network also extended the reach of its lines considerably. Many of the branch lines only ventured into the nearer suburbs established during the Industrial Revolution, and under the main-line management they were rarely extended to newer (particularly residential) suburbs or those deeper in the countryside. The EDR was under government mandate to address this shortcoming [pun not intended] and extended all four of its initial routes by more than 40% by 1980, and another 30% by 1990.

Coverage was further extended in the 1980s and 90s by two new routes (5 and 6) and branch lines from its other routes. Line 5 connected to the tunnel of Line 1, and Line 6 to that of Line 4, to avoid new tunnels. Improvements to signalling and rolling stock were implemented in phases from 1992 onwards to enable trains to move in smaller blocking zones. Most recently, Line 7 was completed in 2009, and further extensions of the other lines have also continued.

In the late 90s, EDR took over running of commuter services on the main lines, which ran through some of the largest suburbs of the capital city. Though main-line operators would have preferred these trains to run on parallel railways, this was not done out of budget constraints. Instead, parts of the main lines were hextupled in proximity to the city, for the accommodation of commuter trains, between 1980 and 1990. Their operation was transferred to EDR between 1998 – 1999.

Lines

Fare

Infrasturcture

Much of the rural and suburban infrastructure operated by the EDR were inherited from the main-line railways and subsequently upgraded, but tunnels and stations in the city-centre were largely built between 1965 and 1994 specifically for its operation. Three entirely new lines have been built during the same time period to serve newer communities.

Stations

EDR stations can be found at ground level, elevated, or underground. The majority of stations in rural areas are at ground level, being true also formerly of the branch lines. Elevated sections occur typically when the lines were extended and cannot avoid going through a settled area. Underground stations are mostly found in the centre of Kien-k'ang, where the cost of purchasing land along the route would be prohibitive: the EDR is only liable for minor compensation for the land under which its tracks go.

Where it is inherited and where geographic permits, the EDR station will have a headhouse containing a ticketing office. Bathrooms where they did not exist have been introduced to all EDR stations. The scale of headhouses tends to be small in commuter suburbs as the station expects commuters to trickle in and out during morning and evening rush hours, but in the urban centre stations expect large, simultaneous boarding and alighting volumes and so have larger internal spaces. The size of the ticketing office corresponds to the expected passenger volume. Automatic ticketing machines have been introduced to the EDR network in 1980, though many of its patrons commute with a seasonal ticket, which not only obviates queuing for tickets but also offers discounts.

One part of the initial EDR project in the 60s is to integrate its stations with existing subway stations, which would be necessary to meet the transit requirements of large numbers of passengers alighting in the urban centre. When commuters alighted at Twa-ts′uk-men, they dispersed by the four subway lines that served it already in the 60s. New stations to alleviate pressure from Twa-ts′uk-men would need to accommodate adequate throughput lest commuters be stranded waiting for the next leg of their commute (the so-called "people jam" and "staircase bottleneck" problem). Accordingly, the best places to establish new commute stations would be those rapid-transit stations where multiple subway lines intersect; however, these stations were also the most challenging to build, owing to the need to avoid disturbing existing subway lines.

New commuter stations were thus constructed at great expense and at a deeper grade under the transit network, whose deep-level lines were typically dug at 25 – 30 m under surface. At new commuter stations, platform levels were 45 – 50 m underground, descending to 65 m at Twa-ts′uk-men to leave sufficient room for the high-speed rail tunnels. Such deep excavations in turn made staircases impractical, being the equivalent of climbing a 15-storey building, and demanded fast-moving escalators connecting to the subway platforms.

Platforms

EDR platforms are designed or modified to handle expected passenger volumes more explicitly than most older platforms, particularly on the subway network, where structural soundness was a greater challenge in its day. For the most part, this means wider platforms with more escalators in the stations where commuters arrive at and leave the city. Escalators and elevators located on the platform also reduce the effective width of the platform, potentially creating unsafely narrow bottlenecks, an issue which has been painfully made evident by accidents at the platforms at Twa-ts′uk-men.

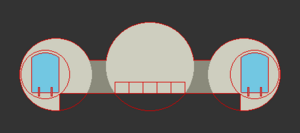

At the new stations, engineers adopted the "three tunnel", with two tunnels for the tracks and one between them to create a wider area. Regulations provide that platforms must have at least 2 metres of continuous and unobstructed space for each track, and this is exceeded in some examples. To conform to it, track tunnels diverge and enlarged in the stations to create a platform, and space between the bores are lined with pillars for structural soundness. The escalators are located in the middle bore. For the stations with the highest expected capacity, as many as five escalators are used in parallel, with all but one operating in the direction of the expected flow.

The height of EDR platforms on its own network is 12 in (0.30 m) above the top of rails, which is level with the internal floor height of its double-decker coaches. For this reason, standard, modern National Rail rolling stock cannot be safely used on the EDR network because their doors would be too high, even though the trains themselves are not out of gauge; however, older National Rail designs, which expected a platform height of 15 in (0.38 m), can safely run through EDR tunnels and load and unload passengers at its stations. This in fact occurred for a number of years earlier in EDR's history as it bridged a shortfall of rolling stock. On trains run by the EDR on National Rail's track, the platforms are shared between the two operators and are thus the same height, at 1.25 m (49.2 in).

EDR platforms have a standard set of features that the operator maintains for a consistent experience. These include timetables, maps of the surrounding area, signs for amenities and connections, train information, and general design language. There is at least one route map and map of the surrounding area on each side of the platform, generally placed near the entry in stations with low passenger volume, but often more copies in others. Standard EDR signs have a black background and white text for good contrast as well as a minimum font size. Starting in 1979, CRT monitors have been employed to display the destinations and status of arriving trains, augmenting the posted timetable. There are also warning lights inset into the platform to warn passengers of approaching trains.

Rolling stock

EDR has generally sought to employ a limited and standardized set of rolling stock for ease of maintenance and consistent experiences. The network was upgraded in the 60s to accommodate double-decker trains, which are still the main style in use today.