Expressways of Menghe

| National Trunk Roads 간선 고속 국도 / 幹線高速國道 Gansŏn gosok gukdo | |

|---|---|

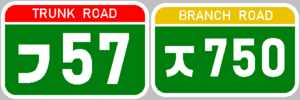

Numbering signs for national expressways (left) and national highways (right). | |

A map of Menghe's expressways. As of July 2019, orange sections are open to traffic, and green sections are under construction or have been budgeted. | |

| System information | |

| Maintained by Ministry of Public Transportation | |

| Length | 32,381 km (20,121 mi) |

| Formed | 1988 |

| Highway names | |

| Expressways | ㄱ## (G##) |

| National highways | ㅈ### (J###) |

Expressways in Menghe (간선 고속 국도 / 幹線高速國道, Gansŏn gosok gukdo), also translated as trunk roads, are a network of controlled-access highways built and maintained by the Ministry of Public Transportation. They should not be confused with the Menghean highway system (지선도로 / 支線道路, jisŏndoro), a network of smaller-volume limited-access roads which feeds and supports the expressway system. Menghean expressways are built and managed by the national government through the Ministry of Public Transportation, though their numbering scheme is regionally based.

Prior to the 1990s, Menghe had no controlled-access expressway system, though it did have a few regional limited-access highways. The expressway construction boom began after Menghe's economic reforms, which intensified the demand for transportation infrastructure and created a lucrative road construction industry. The expressway network rapidly grew from 83 kilometers in 1994 to 34,000 kilometers in 2019, linking all cities with a population of over 500,000.

History

Ancient precursors

For most of Menghe's history, long-distance travel between major population centers was primarily conducted by water. The Meng and Crane River basins each linked a large number of cities, allowing barges with passengers and bulk goods to travel more cheaply than carts on land. Over the centuries, engineering projects like dams, weirs, and locks extended the navigable distance up tributary rivers, and canals allowed movement between different river basins.

Organized long-distance road construction mainly served frontier areas where water was scarce, and mountainous areas where a safe overland route was needed. Emperors in the Kang dynasty famously standardized the length of cart axles so that dirt roads would be of even width in rural areas, though enforcement was likely inconsistent.

Early 20th century

Under the Federal Republic of Menghe, automobiles were extremely rare in Menghe, a curiosity reserved for the wealthiest businessmen and some politicians. This situation persisted up to the Greater Menghean Empire, even as cars and trucks began to spread in Casaterra. The Emergency Fuel Law, passed in 1937, imposed a strict need-based licensing scheme for automobile ownership, essentially restricting car use to the top levels of the political and economic elite.

Consequently, the country's road networks remained in a poor state, with very few paved roads outside major cities. Railroads and waterways still dominated inter-city transportation, and even car owners generally kept their vehicles within the cities and suburbs, using trains for long-distance trips.

The lack of roads became a noticeable problem for Allied forces in the final months of the Pan-Septentrion War, especially as the monsoon rains of Summer 1945 turned the dirt cartways of the southern plain into a sea of mud. The problem would grow more persistent during the Menghean War of Liberation, as Allied and Government troops struggled to reinforce and supply outlying positions where rail lines were absent or had been sabotaged.

First highway network

Interest in a nationwide highway network first came to fruition in the 1970s. Sim Jin-hwan, leader of the Communist Party's "productionist faction," hoped that improved infrastructure would aid the country's economic recovery by helping supplies flow between mines, factories, and cities. Leaders of the Menghean People's Army also believed that highways could help motorized units move quickly around the country in response to an amphibious landing or border incursion.

A plan submitted in 1973 proposed a "rhombus on a chain" network, which would run from Baekjin to Emil-si. At Dongrŭng, the highway would split in two, with one branch linking Taekchŏn, Junggyŏng, Hwasŏng, and Insŏng on the central plain, and the other linking Anchŏn, Hyangchun, Haeju, Daegok, and Myŏng'an along the coast. The two lines would then meet at Sunju and proceed to Bokju and Emil-si, then possibly to the Maverican border.

This plan was ambitious for the time, given Menghe's limited economic resources and the challenging terrain on the coastal route. Only two sections were completed by the time of Sim's ousting in 1980: one from Baekjin to Dongrŭng, and one from Emil-si to Insŏng. Portions of the Dongrŭng-Hyangchun section were under construction, though the rough terrain had led to deadly accidents and landslides.

Though the DPRM had experienced a reasonably fast rebound in growth after the devastation of the wartime years, incomes remained very low across the country, and car ownership extremely scarce. Private automobiles were effectively limited to members of the Communist Party, and even then they were subject to a long wait list. At all times of day, the lanes were eerily empty save for government cars, cargo trucks, and sometimes columns of military vehicles. Large stretches of both highway routes lacked roadside petrol stations, forcing drivers to either fill the tank before leaving or barter for fuel at a factory along the way. The network was also merely limited-access, with intersections (many manned by traffic police), at-grade rail crossings, and many pedestrian and animal crossings, most of them improvised.

Ryŏ Ho-jun halted funding for the highway program shortly after coming to power, and purged the heads of the Ministry of Public Transportation, who were part of Sim's ousted faction. In 1984 Ryŏ took this agenda one step further, sending work teams to tear up large sections of the Baekjin-Anchŏn highway so that any invading force from Dayashina would have to contend with the same poor infrastructure that had existed in the War of Liberation. This proved immensely disruptive to industry in the northeastern region, especially after landslides undermined several of the dirt roads intended as replacements.

Reform era and beyond

Following the Decembrist Revolution of 1987, the Interim Council for National Restoration decisively shifted its priorities to economic reform and modernization. The new government's first Minister of Public Transportation, Yun Gi-ha, was formerly involved in planning Sim Jin-hwan's highway system, and immediately expressed interest in reviving the project. Choe Sŭng-min supported Yun's approach, believing that improved infrastructure wound open the way for rapid growth and revitalize the ailing economy.

Yun's long-term proposal for a national expressway network drew on plans that stretched back to the 1970s, but called for true controlled-access motorways, and relied on more modern interchange designs. It also placed greater priority on linking inland manufacturing regions to coastal trade ports, a major priority for the reformist government. The first expressway to begin construction was a 162-kilometer stretch between Insŏng and Sunju, which included a 2.4-kilometer bridge over the Ro river at Sohŭng. Work on this section began on 23 December 1988, but it was not opened until 6 July 1995 due to delays in building the bridge itself. A simpler 83-kilometer section linking Chanam to Myŏng'an began construction in February 1989 and opened in November 1992, making it Menghe's first operational expressway. This section steadily expanded to Onju (1994), Chŏnjin (1995), Sangha (1997), and Hwasŏng (1998), at which point it totaled over 550 kilometers. To simplify construction, it remained on the east bank of the Meng river for its entire course, using existing road-rail bridges at Chŏnjin and Hwasŏng to link traffic from the other side. Work on the east coast line proceeded more slowly, hindered by mountainous terrain, but engineers used repair work on sections sabotaged under the Ryŏ regime to repurpose existing highway sections into controlled-access roads with higher design speeds and added lanes. An expressway linking Songrimsŏng and Baekjin began construction in 1995, but work on its terminal bridge over the White River to Polvokia was suspended between 1997 and 2002 due to instability surrounding the Polvokian Civil War.

Many of these early expressway projects, built on accelerated timetables with limited oversight, were sometimes marred by political interference and hasty construction. Labor rights were also weak, with frequent complaints about undocumented overtime, missing back pay, and safety code violations. Corruption was a persistent issue, with city officials skimming money off of construction contracts and bribing inspectors for expedited approval. After a hillside section of G03 collapsed during heavy rain in 2000, killing thirty-four drivers and passengers, the Ministry of Public Transport launched a comprehensive crackdown on corruption and code violations in the expressway system, though less severe problems, especially in labor rights, persist to the present day.

As the years passed, Menghe developed a very competent road infrastructure industry, with experience and equipment from one project carried on to the next. Competitive bidding in place of SOE contracts helped drive down costs, as did efforts to root out corruption, and before long the education system was producing large numbers of skilled civil engineers. The Ministry of Public Transportation's goals expanded in tandem. A policy document issued in 2004 laid out a plan for a "national trunk road grid" linking all cities with a population above 500,000 before 2020, while adding additional bypass sections to lighten traffic in densely populated areas.

Terminology

Since 1992, Menghean law has distinguished between two categories of high-volume motorway. The uppermost category is known in Menghean as Gansŏndoro (간선도로 / 幹線道路), "trunk roads," or more formally Gansŏn gosok gukdo (간선 고속 국도 / 幹線高速國道), "national high-speed trunk roads." Depending on Anglian terminology, they are akin to expressways, motorways, or freeways, in that they have no intersections, stoplights, at-grade crossings, or direct property access.

The next category down consists of Jisŏndoro (지선도로 / 支線道路), "branch roads" or "feeder roads"), or more formally Jisŏn gukdo (national branch roads). These have some intersections and at-grade crossings, and may feature direct access to property, though not as frequently as local roads and streets. They also feature different signage and numbering rules, and generally do not include tolls.

Generally, Anglian-language literature from Menghe refers to Gansŏndoro as either "trunk roads" or "expressways," and Jisŏndoro as either "branch roads" or "highways." Neither translation is official, though, and a confusing array of other versions exist, including "main roads," "branch highways," "general roads," and so on.

Characteristics

Numbering scheme

Menghean expressway numbers begin with the Sinmun component ㄱ, or "G", for gansŏndoro. This contrasts with the prefix ㅈ ("J") for jisŏndoro. When read aloud, the prefixes are generally pronounced gan and ji respectively, rather than giŭk and jiŭt. Some Anglian-language travel guides encourage visitors to think of these symbols as "J" and "T" respectively, but this can cause confusion as ㅈ is romanized as J.

Expressway shields use a rectangular box with a red bar running across the top, while highway shields use a rectangular box with a yellow bar. Since 2009, the bars have contained the Anglian words "Trunk Road" and "Branch Road" respectively.

All expressways use a base designation composed of a two-digit number, e.g., ㄱ02 or ㄱ55. On the first few expressways, the number reflected the order in which the expressway project had been approved by the Ministry of Public Transportation. In 2003, the MoPT approved a new scheme in which the first digit reflects the postal code of the region in which the expressway has most of its course. The second digits are even for north-south roads, and increase from east to west, while for east-west roads they are odd and increase from north to south. The numbers 01 through 03 were retained for the first three "core" expressways, each of which runs from the far south to the far north, and a few years later the numbers 04 and 05 were assigned to two newly completed expressways of similar length. With eight regions, the initial digit 0 is reserved for these "core trunk roads," and the initial digit 9 is reserved for spillover cases in which a region has more than five north-south or east-west expressways. Thus far, only the partially complete G90 expressway south of Donggyŏng has used a 9# designator.

Ring roads surrounding cities add -0x to the end of the expressway number, with x denoting the ring road's order from the center of the city. Connections or relatively short expressway sections add -1x to the end, with x generally increasing north-south or east-west. In a few cases, where a supporting section of expressway is built parallel to an existing section, it adds -2x to the end. The southern city of Sunju, for example, has three ring roads numbered G0201, G0202, and G0203, and two inter-ring-road connections numbered G0218 and G0219.

Exit signage

Exit numbering on the national expressway network follows a distance-based system, with each exit numbered by the last three digits before the decimal point of its distance along that route. For example, an exit at kilometer marker 782.9 would be Exit 782. If there are multiple exits within the same one-kilometer stretch, they are distinguished with consonants of the Menghean Sinmun alphabet: e.g., Exits 782G, 782N, 782D, and so on. Exit numbers use green letters in a white hexagon on a green background, in reverse of regular expressway number signs.

Exit numbering does not reset where an expressway crosses a provincial boundary, but it does reset every 1,000 kilometers, moving from 999 to 0. Exit numbering may also reset in cases where an expressway is extended backward beyond its original zero point, or where two separate stretches opened to traffic before the section between was fully planned. Exit signs appear at regular intervals ahead of the exit in question - usually every 4000, 2000, 1000, and 500 meters, with a sign above the exit itself - and grouped signs show the distance to the next two or three exits.

Rest stop signs use a blue background and white lettering, and list the amenities available as well as the attached exit. Rest stops on the Menghean expressway networks are divided into four categories: G (parking only), N (parking and fuel), D (parking, fuel, and restaurants), and R (parking, fuel, restaurants, and a motel). Additional amenities, including car repair shops and electric vehicle charging facilities, are marked with icons.

Recent expressway construction in Menghe has favored smoother merge systems, with fewer forced merges and zipper merges, especially in interchanges. These features nevertheless remain common in older areas, especially on ring roads around cities.

Border crossings

As of June 2019, the Menghean expressway network has six operational border crossings. A seventh, the Menghe-Argentstan Friendship Bridge, formerly known as the Menghe-Innominada Friendship Bridge, is scheduled to open to traffic in 2020. Of the six operational crossings, three lead to Polvokia, two lead to Dzhungestan, and one leads to Argentstan.

Cars and trucks at all six crossings are stopped for inspection at official checkpoints, where they must pass customs inspections and present valid travel documents. Officers at these checkpoints are employed by the General-Directorate of Immigration and Personal Registration, a body of the Ministry of Internal Security. All three destination countries are members of THETA, and the Menghean government has taken steps to speed up inspections as a way of encouraging trade and travel. Inspections nevertheless remain long and rigorous at the border with Argentstan, due to concerns about smuggling, illegal movement, and terrorist activity by individuals affiliated with Maverica and the Innominadan opposition. IIA investigators have been known to conduct surveillance and surprise inspections at the Argentstan border crossing, particularly against persons of Maverican creole or Innominadan descent.

Military role

A common misconception about the Menghean expressway network is that it was designed with long, straight sections of road which could be converted to airbases in wartime. This appears to be a misinterpretation of Menghe's Homeland Defense Airstrip System, which does make extensive use of roads as airstrips; HDAS, however, uses public roads and minor highways, not the expressway network. Certain expressway sections are marked on civil and military aviation maps and can be used as emergency landing sites if an aircraft is unable to reach the nearest runway, but these sections are not outfitted for use as semi-permanent military airbases, and lack the facilities present at HDAS sites.

Rather, the main military role of the Menghean expressway network lies in its usefulness for fast road transportation. The density of expressway coverage is relatively high in the southwest, particularly the Daristan Semi-Autonomous Province, even though this is one of the more sparsely-populated areas in the country. In a major conventional war with Maverica, these roads would play a key role in bringing supplies to the front lines and supporting the flow of reinforcements. The lack of HDAS bases on the expressway network likely stems from military concerns that flight operations would interfere in the movement of road vehicles.

Regulations

Speed limits

Most expressways in Menghe have a maximum speed limit of 120 kilometers per hour (75 miles per hour). In tunnels or winding sections with a lower design speed, this may be reduced to as low as 80 km/h (50 mph) for driver safety. The fastest section on the entire network lies on a long, straight stretch of the Sunju-Insŏng segment, where the speed limit rises to 150 km/h (93 mph).

Minimum speed limits of 80 km/h (50 mph) are also enforced on 120-km/h-and-above sections, and in some areas the passing lane has a minimum speed limit of 100 km/h (62 mph). Minimum speed limits are enforced by traffic police.

Menghean expressway law requires a three-second following distance between cars, which translates into 100-meter spacing at 120 kilometers per hour. Like the minimum speed rule, the spacing rule is relaxed during heavy traffic, but enforced by police when traffic is flowing.

Vehicle types

As per standard motorway terminology, only powered vehicles are allowed on Menghean expressways. Pedestrians, bicycles, and animal-drawn carts (still present in some rural areas) are not permitted. Vehicles unable to reach the minimum speed limit of a section of expressway, such as tractors and construction vehicles, are also denied access, except for construction or repair work on the expressway itself.

A national law passed in 2008 outlaws the use of motorcycles, mopeds, and three-wheeled vehicles on expressways, though not on limited-access highways, citing concerns over safety and visibility to other drivers. Police and military motorcycles are exempted.

Tolls

When Menghe's first expressways opened in the 1990s, all of them featured tollbooths at the entrances and exits, and at regular mid-course intervals. Because vehicle ownership was low, this had only a small effect on traffic flow, and most vehicles were owned by either well-connected individuals or state-run enterprises, the Menghean Socialist Party defended the tolls as a form of progressive taxation which would be phased out when the construction loans were paid off. These initial tolls were paid either in cash, or with "toll stamps" (tonghaengpyo) which could be purchased at a convenience store.

As traffic loads increased, the Ministry of Public Transportation began to phase in an electronic toll collection option to ease congestion and speed up travel times. Drivers who opted in could purchase a transponder and mount it on the windshield, and would receive an automated bill to a prepaid expressway pay account. Cash-based stations were retained in half of all lanes at tollbooths for drivers who lacked transponders, and cameras were installed to identify violators at e-collection gates. 45% of Menghe's expressways had e-toll stations at the end of 2012, the year the project was launched.

In 2016, the Bonggye-Insŏng section of the G02 expressway experimented with open road tolling, replacing conventional tollbooths with overhead scanners and cameras. Unlike previous e-toll systems, which required drivers to slow down, this system could work at speeds of up to 140 km/h over regular stretches of expressway. If a driver lacked a transponder, a camera on the overhead structure would photograph the car, read the license plate, match it to the vehicle owner's registered address, and send a bill by mail. Greater flexibility in speed and lane space allowed these transponder stations to be installed over all expressway on-ramps and exits, billing each car by distance traveled.

Evaluations of the Bonggye-Insŏng system were apparently well-received at the MoPT, which announced in 2018 that the same infrastructure would be gradually expanded to the rest of the expressway network. This announcement also laid out a new toll pricing system: the first 25 kilometers of travel per car per day are free of charge, subsequent tolls are charged on a standardized per-kilometer basis, and after 200 kilometers the per-kilometer fee sharply declines. Certain bridges and tunnels may charge an extra fee, enforced by readers at the start and end. Congestion tolls can also be added for travel on high-volume road at rush hour. Citizens are encouraged to register on the MoPT's online portal with their Resident ID number and either set up a pre-paid account or link the billing program to a bank account, credit card account, or major e-pay app. License plates and transponders registered to heavy lorries are charged at a higher rate. The system is slightly different for drivers of foreign vehicles, who can purchase a prepaid toll card at a border crossing and register it under their license plate.

Critics of the new open-road tolling system have argued that it doubles as a centralized mass surveillance system. Any time a car passes under a toll arch, the system logs the location, date, time, and license plate into a central MoPT database, allowing the government to record the movement of vehicles around the country. In several high-profile criminal cases, Menghean police reported using toll arch data to track down fleeing suspects, and there is speculation that the IIA and Internal Security Forces use it to monitor the movement of dissidents and threat-list members. Traffic police are also known to issue speeding tickets by mail if toll arch time logs show that a vehicle's average speed over a given course of expressway exceeded the limit.

Expressway tolls as a general measure have also drawn criticism for their relatively high charges in a middle-income poverty. Especially in rural areas, many residents complain that they are unable to afford regular travel on expressways built through their home prefectures, especially where these include high-toll bridges, tunnels, or viaducts. The NSCC has made repeated appeals for reduced tolls in recent years, with mixed success in the form of a 25-kilometer free travel distance. In MoPT policy circles, defenders of expressway tolls argue that they are necessary for paying off construction debts and conducting quality upkeep, and that charging on a per-kilometer basis is more progressive than raising income taxes to pay for road maintenance.