Menghean War of Liberation

| Menghean War of Liberation | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Clockwise from top left: bombing of Jinjŏng, 1946; Eighth Army soldiers defending Suksŏng, 1952; Tyrannian patrol in Ryŏngsan, 1953; civilians fleeing the Communist advance, 1964; MLA troops enter Dongchon, 1964; Communist guerillas in Sanhu, 1956. | |||||||

| |||||||

| Belligerents | |||||||

|

| ||||||

| Strength | |||||||

| 2,600,000 (1961 est.) | 1,400,000 (1960 est.) | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | |||||||

| 1,200,000 - 2,000,000 military dead | 450,000 military dead | ||||||

| 6,000,000 civilian casualties (est.) | |||||||

The Menghean War of Liberation (Menghean: 멩국 해방 전쟁 / 孟國解放戰爭, Mengguk haebang jŏnjaeng), also known internationally as the Continuation War, was a civil war fought in Menghe between a variety of communist and nationalist insurgents, later unified into the Menghean Liberation Army, and the Republic of Menghe government, which succeeded the Menghe Occupation Authority. The war is conventionally dated from 9 November 1945, Menghe's surrender in the Pan-Septentrion War, to 27 July 1964, when the Allied powers signed an armistice with the DPRM. The victory of the communist forces led to the establishment of the Democratic People's Republic of Menghe, which was officially proclaimed on 4 April 1964.

The conflict began as a direct continuation of the Pan-Septentrion War, when large portions of the Imperial Menghean Army refused to acknowledge the surrender proclamation issued by Emperor Kim Myŏng-hwan. Confident that the invading Allies could be repelled by the heavy bloodshed of a guerilla war, the nationalists retreated into the mountains, arming themselves from wartime arsenals and workshops. Mop-up offensives by Allied ground troops and the resumption of strategic bombing steadily broke apart these last holdouts, but only slowly; conventional fighting against nationalist troops lasted for seven years, compared with a little over one year of fighting on Menghean soil during the Pan-Septentrion War.

The last of these offensives, launched in 1952, forced the Eighth Army, the largest group of nationalist holdouts, to retreat 1,200 kilometers through the Chŏnsan Mountains, at an enormous cost in life and materiel. With conventional resistance defeated, Menghean resistance forces turned to guerilla warfare and rural insurgency, arming themselves with weapons smuggled across the Polvokian border. Nationalists like the Eighth Army survivors initially clashed with Communist insurgents, but in 1958 the two formed an alliance of necessity, agreeing to cooperate in return for a power-sharing agreement after the war.

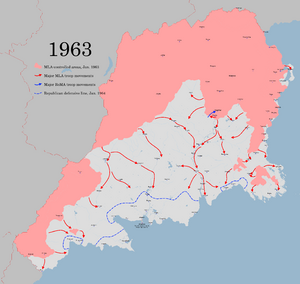

Having united their forces, opened new arms smuggling conduits, and planted new insurgent cells in the south, the resistance forces, calling themselves the Menghean Liberation Army, took the offensive in 1961, seizing a broad band of territory in the north. Encouraged by their successes, guerillas in the south rapidly expanded their attacks. Republican forces counterattacked to stop the Communist advance, but the demoralized Republic of Menghe Army collapsed in combat, and the Tyrannian and Sylvan troops supporting them were too small in number to turn the tide. By the summer of 1964, the Menghean Liberation Army controlled all of Menghe's prewar territory, save for the Sylvan enclave of Altagracia, which they were unable to take successfully. An armistice agreement signed on July 27th concluded the war, ending almost 32 years of continuous warfare, 20 of them fought on Menghean home territory.

Names and periodization

Within Menghe, the period of fighting between 1945 and 1964 is known as the Menghean War of Liberation (멩국 해방 전쟁 / 孟國解放戰爭, Mengguk haebang jŏnjaeng) or the Fatherland Liberation War (조국해방전쟁 / 祖國解放戰爭, Jŏguk haebang jŏnjaeng). It is usually shortened to War of Liberation (Haebang jŏnjaeng). A number of longer official titles exist, including the "nationwide anti-imperialist anti-capitalist glorious war for the liberation of the fatherland."

In the countries that assisted the Republic of Menghe during its fall, including Tyran, it is known as the Continuation War. The name refers to the fact that it picked up almost immediately after the end of the Pan-Septentrion War; many newspapers and politicians treated it as a final phase of the PSW itself, though by the 1950s it came to be seen as a separate conflict. In the Republic of Menghe it was known as the Menghean Civil War (멩국 내전 / 孟國內戰, Mengguk Naejŏn), a term which remains in use with the Menghean Government in Exile.

Other differences relate to the war's periodization. Conventionally, the conflict is broken up into three stages: 1945-1952, when the main resistance forces were rogue units of the Imperial Menghean Army; 1952-1960, when the communist insurgency rose to prominence; and 1960-1964, when the insurgency boiled over into a conventional war as guerillas linked together regional power bases and formed a large ground force complete with combat vehicles shipped in from Polvokia and Maverica.

Background

On November 7th, 1945, faced with threats of a third nuclear attack on Anchŏn and still viewing the devastation of firebombing in Donggyŏng, Kim Myŏng-hwan sent a message through a neutral embassy that Menghe was willing to surrender if the Allied victors could hold to three conditions. First, Menghe would remain a sovereign country rather than an imperial territory; second, it would not be reduced or partitioned beyond its 1933 borders; and third, there would be no genocide or ethnic cleansing against the Meng people. After two days of negotiation, Allied diplomats agreed to the conditions, which were consistent with their demands against Menghe, and dispatched a letter accepting Menghe's surrender.

Kim Myŏng-hwan and his top ministers announced the surrender to the public on November 9th, which is generally regarded as the end of the war in Menghe. After finishing the speech, Kim appointed his first deputy minister as interim head of state to manage the surrender, then retired to his personal quarters in the Donggwangsan palace. He committed suicide later in the evening, cutting his throat with his ceremonial sword.

News of the surrender came as a complete surprise to many political hardliners and military commanders, who were under the impression that Menghe was in a position to continue fighting. To avoid undermining morale, negotiation had taken place through back channels, without the knowledge of top military leaders. Navy commanders, who had been resigned to the poor chances of victory since 1942, unanimously agreed to comply with the surrender agreement. Responses in the Army were more mixed.

Generals in the Chŏllo Plains Front, who had endured heavy losses in the final months of the war, ordered a halt to all operations when news of the surrender reached their positions, and sent officers across the front lines with white flags to announce their compliance with the surrender. The Eighth Army, further north, refused to turn over its personnel as prisoners, maintaining a standoff at the front. Other commanders further north in Chikai province followed the Eighth Army's example. Rear-line commanders and reservists who had not yet seen combat called for a resumption of fighting. Before long, a rumor was spreading through sections of the high command that Kim Myŏng-hwan had been assassinated by members of his civilian cabinet after reading the surrender instrument at gunpoint.

This ambiguity had a deep foundation. Even before the coup of February 1927 that placed Kwon Chong-hoon in power, recruits in Menghe's armed forces had been inculcated with the belief that it was their duty to fight to the end in defense of Menghe's sovereignty; after the coup, and especially after the beginning of the war, these teachings had spread to the whole population. Even as the war turned sour, the Imperial Menghean Army's high command favored a "war of resistance" strategy, hoping to leverage Menghe's large population and rough terrain to bleed the invaders until the enemy public lost the will to continue the war and agreed to a withdrawal. One internal document estimated that the cost to Menghe would near 10 to 20 million deaths, and added that "while such losses are tragic they are a small price to pay for independence." By 1944, citizen militia in many villages were already training with bamboo spears, and rural warehouses were turning out simplified rifles en masse. In the eyes of the Army's nationalist leaders, the surrender decision was not only at odds with military honor, but also unnecessary given the present war situation.

1945-1952: The Continuation War begins

Yang Tae-Sŏng's broadcast

General Yang Tae-sŏng, 8th Army Commander, Broadcast to the Troops of the Menghean Ground Forces (excerpt)

Yang Tae-sŏng, the commander of the Eighth Army, broke the silence on November 12th, recording a radio message in which he called upon "patriotic commanders and soldiers" to carry on the fight against the Allied forces as guerillas and resistance fighters. The message was broadcast locally on the Eighth Army's own radio network, and despite a hasty effort by the civilian government to post troops outside of radio offices, several civilian towers broadcast the message as well.

Responses to the broadcast varied, with some commanders declaring that they would follow Yang's call for a war of resistance. Others denounced it as treason and moved behind the surrender agreement. One lieutenant's diary records a typical intermediate response: "A member of the Regiment Commander's staff came into our barracks on the 14th. In plain language, he stated that the commanders would adhere to the surrender, but that any officers and enlisted personnel who wished to take part in the resistance had until sunrise to gather their weapons and belongings and move out of the camp. They would be marked as deceased on the personnel register during the official surrender."

The Eighth Army itself retreated under the cover of darkness on the 15th, moving back into the Suksan mountains to the northeast. Rear-guard units maintained a security perimeter against counterattacks, and demolished bridges after the last units had passed. Allied commanders declined to launch a pursuit, still holding out hope that once Menghe's political situation stabilized, the Eighth Army would agree to the surrender. In time, they would come to regret this decision.

Operation Henhouse

In other areas of Menghe, where regular Army units had mostly disbanded, Allied forces faced a different crisis. Morale among surrendered troops was dangerously thin, and the full extent of the Army's reluctance to surrender was becoming apparent. Where units did turn over their men and equipment, inventory and personnel lists showed signs of last-minute alteration, with large numbers of weapons and personnel missing or unaccounted for.

Realizing what was going on, Tyrannian commanders hastily organized and carried out Operation Henhouse, a breakneck campaign to seize control of all divisional camps, armories, and munitions factories in Menghe to pre-empt further militia defections. Before the instrument of surrender had even been signed, motorized columns raced inland among the major roads, broadcasting news of the surrender as they went. As soon as the main coastal airfields had been turned over, airborne and air-mobile forces joined the effort.

Across the Chŏllo plain, Menghean forces remained compliant, if resentful, with the searches. Elsewhere, hostilities prevailed. A train full of Tyrannian soldiers was derailed by a bomb while passing over a bridge in Ryŏngsan Province, killing nearly all aboard; units following along roads were turned back by rifle fire from the hills. Spies in villages spread news of the soldiers as they approached, giving warehouse commanders time to hide weapons or disperse personnel. Army Aviation units begant to flee the country entirely, flying their planes across the border to Polvokia, which was neutral. Fearful of retaliation, the Polvokian government returned many of the pilots, but kept the planes.

More worrying, in the longer term, was what Allied soldiers found when they arrived at their objectives. Nearly all of the arsenals were missing some of their stockpiled weapons, a problem the local guards attributed to wartime shortages; some had been emptied entirely. Some factories had entire machining tables missing, the bolts for mounting them still protruding from the floor. The list of stockpiles and factories passed on by the civilian government also omitted the vast network of rural production sites set up under the homeland defense plan, as many of these had never been centrally documented to begin with. For the time being, the country's major cities, railroads, and factories were under control, but the mountains and forests were rumored to be teeming with soldiers.

The situation was more serious in the north. Following the Eighth Army's example, army groups opposing Hallian forces had banded together into the Northwestern Emergency Government, with Marshal Bak Ho-jin as acting head of state. After news crossed the front lines that Menghean forces were refusing to surrender, Hallian commanders ordered a resumed offensive, pushing toward Jinjŏng and Kanghap. Heavy resistance delayed their advance, and gave Menghean forces time to fan out through the countryside in depth, seizing control over factories and refineries owned by the civilian government.

The Occupation Authority

While Operation Henhouse was underway, and as Hallian and Menghean troops traded fire in Chikai province, the surrender agreement itself was signed. The Menghean government offered to conduct the ceremony in Donggyŏng, but the Allies insisted on a southern city, as the Imperial Dayashinese Navy still represented a threat to any ships sailing into the East Menghe Sea. Representatives of Menghe's transitional government responded by traveling by train to Sunju, signing the official instrument of surrender on December 5th at a relatively unscathed villa outside the city. With the agreemnt signed, and the civilian government formally capitulated, the Allies began the work of setting up an Occupation government to administer the country.

The resulting Provisional Council for the Occupation of Menghe (PCOM) was jointly overseen by two Allied generals, one Tyrannian and one Hallian. This joint structure soon led to disagreements on how to proceed. Tyrannian officers wanted to thoroughly dismantle Menghe's nationalist administration, removing influential members of the old government and bringing in expats or foreign experts to run the country in the interim. Hallian officials disagreed, fearing that removing too many civil servants would worsen instability.

PCOM also quickly came to realize that they had underestimated the challenges of running a war-torn country as large and impoverished as Menghe. While the Allies did send food aid in response to news of shortages, they severely underestimated the scale of the problem and the extent of the damage to transportation infrastructure. A Tyrannian scheme to replace regime-aligned landowners in Chŏllo with Occupation sympathizers running large estates further disrupted food production, and sparked resentment among peasants, who refused to hand over their crops. Coupled with a dry monsoon season in 1946, these problems culminated in a famine that may have killed as many as five million people. Rising food prices in the cities intensified Menghe's hyperinflation, which had already taken off in the last two years of the war as the government attempted to print money to fund continued production. Rumors that PCOM was planning to invalidate the Menghean Won and import foreign currency intensified the problem, rendering existing bills worthless.

In an urgent effort to address food shortages and population imbalances, PCOM adopted its infamous "agrarian resettlement policy." With the help of local police, displaced persons within the cities were rounded up and shipped out to rural areas, threatened with deportation again if they tried to move back. The radical policy was intended to resolve the dual problems of homelessness in bombed-out cities and labor shortages on farms affected by battle deaths and famine, but it proved immensely unpopular, especially when challenges in organization led to rough execution. In many cases, extended families were broken up between areas, and in several cases deportees were deposited in empty fields with no existing buildings or shelter. Up to 10 million people are believed to have been moved in all. In 1964, soldiers of the Menghean Liberation Army would claim to have uncovered minutes from PCOM leadership discussions revealing that the agrarian resettlement policy was part of a deliberate effort to "solve the Menghean problem" by dissolving the country's industrial base and converting it into an agricultural economy; Tyrannian and Hallian authorities still dispute the authenticity of the minutes, which are held at the Museum of the War of Liberation.

Another of PCOM's controversial decisions was its ruling on the status of Altagracia. Under the Treaty of Soon Chu, signed in 1853, Altagracia was leased to Sylva for a period of 99 years. In 1947, representatives of the Sylvan government met with PCOM leaders in Sunju to request that Altagracia be transferred permanently to Sylvan control as compensation for Sylva's losses in the war. After two years of negotiation, PCOM's leaders agreed in 1949, seeing it as a way to maintain Entente bases in Menghe and reward Sylva for its contribution to the war effort. This move set off immediate protests across Altagracia and the neighboring northern territories, at one point bringing crowds to the gates of PCOM's headquarters; fearful that the headquarters could be lost, Tyrannian soldiers opened fire on the crowd, and proceeded to round up suspected ringleaders on charges of insurgent activity. Similar crackdowns took place on the Altagracian peninsula.

In response to the formation of PCOM, Yang Tae-sŏng proclaimed the formation of the Emergency Patriotic United Front for Anti-Western Resistance, known in brief as the Menghean Resistance Front (대멩 항서 전선 / 大孟抗西戰線, Dae Meng Hangsŏ Jŏnsŏn). Due to the presence of Tyrannian troops on the central plains and the destruction of railway routes in the mountains, Generals and Warlords from the other factions were unable to meet in person to coordinate with Yang, but they all pledged allegiance to the new front in short order. Allied press referred to the new alliance as the Nationalist forces.

Strategic bombing resumes

Initially, the Allies sought to defeat Nationalist units with ground forces alone, anticipating a brief mop-up operation. By late December it was becoming clear that this was too optimistic. Bolstered by a large local population, Menghean forces in Jinjŏng and Kanghap repelled repeated attacks by Hallian ground forces, who faced narrow supply lines across the Central Hemithean Desert. Tyrannian forces in the Southwest were unable to reach Daegok and Goksan, as ambushes in the narrow mountain passes of the southwest repeatedly turned them back. Plans to demobilize ground forces were further delayed as the Allies prepared for a long-term operation.

On January 4th, PCOM issued Emergency Order 517, which authorized strategic bombing in areas of Menghe held by the Resistance Front. The order was issued over the protests of collaborating civil servants, who warned that it would intensify opposition; the surrender agreement on November 9th had been issued with the understanding that strategic bombing would be suspended altogether. Tyrannian and Hallian commanders justified the decision on the basis that areas controlled by militia had not yet complied with the surrender agreement and could not be held to its terms.

The resumed bombing campaigns were initially organized on the same basis as wartime ones, targeting barracks, factories, and oil storage tanks under Menghean Army control. Pilots were surprised to encounter a small number of Menghean fighter aircraft, particularly in the Chikai region, where Army forces still controlled oil wells and refineries. Yet with the help of fighter escorts, bombing missions proceeded relatively smoothly in comparison to wartime years.

Before long, bomber command was encountering a different problem: a lack of clear targets. Airfields and oil refineries were the hardest hit, prompting a second wave of aerial evacuations to Polvokia, some of them intercepted by Allied air patrols. But even before the surrender, Menghean commanders had devised strategies to reduce bombing damage, dispersing ground forces' bases and moving small arms production from factory complexes to caves and rural warehouses. The shift from conventional opposition to guerilla warfare intensified this dispersal. Under pressure to keep hitting guerilla fighters, bomber command shifted to more marginal objectives, such as mountain roads, footbridges, and villages suspected of housing enemy soldiers or weapons caches. When Jinjŏng fell on February 9th, Hallian forces estimated that 90 percent of the city's buildings had been leveled; Daegok, captured on May 13th, did not fare much better.

Attacks on infrastructure also had lasting consequences. Dam-busting attacks, easier now that short-range bombers could be brought in, set off serious flooding, in some cases affecting downstream areas in occupation-held territory. The emptying of reservoirs hampered drought relief efforts the following year, and made transportation canals impossible to navigate. Strikes on bridges and railroads did little to slow Nationalist forces, who had taken to moving by foot on mountain paths, but they would make it much harder for government troops to reinforce inland areas in the future.

Transition to counterinsurgency

With heavy air support and no enemy armored opposition, Hallian and Tyrannian forces made steady advances into Nationalist-held territory. Determined to bleed the enemy heavily, Nationalist troops initially responded with head-on counterattacks. The largest of these, at Mungyŏng Pass south of Suksŏng, succeeded in turning back a major Tyrannian offensive into the Eighth Army's zone of control, but at the cost of some 5,000 Menghean casualties. Stalled in the west, Tyrannian forces devoted more troops to the southeast, which held more factories and posed a greater threat to Occupation-held ports. Daegok fell in May 1946 after a two-month battle in and around the city, and Goksan fell later the same year.

Initially determined to fight for every valley, southeastern forces began to re-evaluate their strategy. After the fall of Goksan, General Chi Dae-sŏng reportedly commented that "ten thousand lives are replaceable, ten thousand rifles are not." At Daegok the defenders exhausted their wartime stockpile of artillery shells, then lost the guns they had brought forward to batteries in the mountains. Village machinists continued to turn out emergency-model rifles designed under the late-war plan, but these were of generally poor quality, and their production could not match wartime attrition. The situation was simialr in the northwest, where relentless bombing of ammunition stockpiles and rural arsenals cut into wartime stockpiles.

By late 1947, Nationalist forces throughout Menghe had all but ceased front-line resistance, instead withdrawing into the mountains and forests to fight as partisans. The Eighth Army was the only Nationalist unit that still operated with a clear front line, and its controlled territory consisted mostly of semi-arid highland, far from any valuable transportation routes or population centers. Yet intermittent guerilla warfare continued, with Menghean forces ambushing trains, villages, and occupation patrols in quick hit-and-run attacks, retreating to the hills as soon as reinforcements arrived.

Disagreements on how to deal with the guerillas divided PCOM. Faced with dwindling public support for a long occupation, Hallian leaders began looking for a way out, even as their Tyrannian counterparts called for escalation.

General Immonen, commander of Hallian forces in the Northwest, declared on 23 February 1948 that Nationalist conventional forces no longer posed a threat of foreign invasion and therefore the post-war mission was accomplished. Hallian forces withdrew over the next few months, handing over patrol and policing duties to the provisional Menghean Domestic Security Force. This reversal opened a power vacuum in the north and northwest, allowing guerillas to recover from the harsh losses of 1946 and 1947 while linking up and expanding their operations.

Tyran also began drawing down its conventional ground troops in Menghe, but it stepped up other operations. Focusing first on the southeast, where the guerilla threat was greatest, Tyrannian special forces began launching raids into areas of Nationalist operation, seeking to eliminate high-profile commanders and capture weapons caches. Civilians who resisted were treated as enemy combatants. These "search-and-destroy" missions, among the first of their kind in the modern era, saw the first large-scale experimentation with helicopters as military transports. They also appeared more successful than regular ground operations had been so far, leading to the capture or killing of dozens of top reservist commanders, including Chi Dae-sŏng. Checkpoints installed along mountain roads made it harder for guerillas to supply remote positions or move through the area. In some areas, Occupation authorities experimented with a "fortified village system," relocating farmers from outlying hamlets to central settlements which could be easily defended by police or soldiers. In addition to deterring raids, these changes also made it harder for civilians to pass supplies to the guerillas or join their ranks. Gradually at first, raids on towns and villages in the valleys became less frequent, and supply lines between major cities were secured.

The Eighth Army's retreat

After declaring victory over insurgent activity in the southeast, Tyrannian forces moved to the west, preparing to carry out a decisive strike against the Eighth Army. With the conflict in Azbekistan ended by a ceasefire in 1949, Tyran was able to devote more troops and aircraft to the Menghean theatre, and top commanders predicted that the Eighth Army's prompt defeat would undermine the morale of the remaining Nationalist guerillas. General Anthony William, a veteran of the Khalistan theatre who was held as a POW during the Pan-Septentrion War, was charged with leading the operation. In addition to three divisions of Menghean Domestic Security Force volunteers, they brought along a mountain infantry unit from Reberiya, and part of the special forces unit which had served in the southeast. Two divisions, sent through Maverica and Dzhungestan, closed off Sŏnmun pass to the west, blocking the Eighth Army's only escape route, while the remaining force prepared to attack through Mungyŏng Pass again. The offensive was scheduled for September 1951.

The Suksan basin had long been a natural fortress; five years of wartime planning had turned it into an artificial one. Stone and concrete bunkers lurked around all of its entrances, which formed bottlenecks for any large attacking force. The region's 15th-century castles, already built to withstand cannonballs and earthquakes, were converted into defensive strongpoints. Mountain caves were charted and expanded, many of them converted into concealed firing positions for heavy artillery. Yang Tae-sŏng had very deliberately chosen it as a fallback point, and had planned extensively for the day the attack would come.

The Second Battle of Mungyŏng Pass lasted for two weeks, from September 23rd to October 7th 1951, and once again proved costlier than both sides had anticipated. Extensive high-altitude bombing in the months prior had not silenced the concealed cave batteries on either side of the pass, and many of the tunnels had to be cleared on foot, greatly slowing the operation. Combined with delays in planning and launching the operation, this caused the attack to drag into the winter months. On reaching the banks of Lake Tae, the attackers found that while the ice was indeed thick enough to carry a footsoldier, the defenders had guns on the far hills which could shatter it; the trek around the lake dragged on for months, slowed by artillery and mortar fire from the mountains and ambushes at night. By April 1952, the Allies had besieged the city of Suksŏng along its landward side, and were shelling it from across the lake. A long, bloody battle to take the walls and citadel followed, but the enemy leadership was nowhere to be found; the Eighth Army headquarters had already withdrawn into the mountains, along with the majority of its personnel, leaving behind only a determined force of volunteers to fight to the death inside the city as the rest of the force repositioned.

General Yang Tae-sŏng managed to carry on this cunning defense for another half-year. Rather than making frontal attacks, as he had done at Mungyŏng Pass, he avoided head-on confrontations, instead drawing out enemy forces along the rocky shores and valleys and striking their supply lines at night. Yet Tyrannian forces had learned counterinsurgency tactics as well, and a cautious advance, combined with a thorough effort to search local villages, steadily hemmed in Yang's troops, pushing them northeast up the Ŭm River Valley.

Though many of his lower staff were determined to fight to the death, General Yang began drawing up plans for a withdrawal through the Chŏnsan Mountains, in the hopes of meeting up with guerilla forces in the north. Weather was a constant concern. A winter withdrawal would bring frigid temperatures and deep snowdrifts, while a summer withdrawal would bring stormy weather and flooding streams. His remaining soldiers were also running low on provisions, and after fighting for two years on emergency rations, were in poor condition to cross the highest mountain range in the country. Yang charted a course that would follow the Ŭm, Ro, and White River Valleys, with only two high-altitude crossings in between. The Eighth Army would depart in three columns to spread out its forces, with Yang in the second. To speed up the columns, the ill, wounded, and otherwise unfit were assigned to stay behind and cover the Eighth Army's retreat. Tyrannan soldiers would later report finding some of them strapped to machine-gun posts.

On receiving news that the Eighth Army was retreating, General William ordered the Royal Air Force to reconniter its movement and bomb its columns. Clear weather and a lack of foliage left no cover for the Nationalists, who had already abandoned their anti-air guns in the Suksan Basin. To reduce losses, the Eighth Army sought cover by day and marched by night, which drastically slowed their advance. Even as the weather warmed, other delays took their toll. In May, a bomb-triggered landslide killed many soldiers in the first column, and forced the second to follow a different route higher in the mountains. News of a Domestic Security barricade north of Kaesan forced another, more treacherous detour over a 2500-meter ridge. With only enough supplies for a month and a half of travel and no towns in sight, the soldiers resorted to foraging grass and hunting mountain goats. Only ground opposition was scarce, as General William declined to send troops into the mountains in pursuit, and initially stationed the bulk of his force around Wŏnsan, mistakenly believing that the Nationalists aimed to break out in Samchŏn Province. Salvation finally came in July, when the monsoon rains arrived at the Chŏnsan peaks, buffeting the range with cloud cover. The RAF's relentless airstrikes slowed to a halt, as high-altitude bombers lacked clear visibility, and ground-attack pilots were unwilling to risk blind flights through a mountain range. With the weather on their side and the rain still mild, the Eighth Army survivors made the final crossing to the White River and proceeded rapidly downstream, regrouping at the city of Kunsan to rest and take on supplies. Yang initially planned to make Kunsan his new base of operations, but a devastating bombing attack in early August forced him to set off again, this time for the highlands around Jinjŏng. In all, the journey had covered more than 1,200 kilometers, and lasted over three months.

News of the Nationalists' daring expedition through the mountains spread rapidly across the country, undermining William's claims of a final victory over the insurgents. Among Nationalist sympathizers, the Eighth Army took on a legendary status, and anti-Occupation activity grew increasingly bold. While the soldiers' endurance and determination would make keen propaganda material later on, at the time the Eighth Army was in no position to exploit its newfound fame. Of the 180,000 soldiers who started the march, fewer than 35,000 arrived at their final destination. Yang Tae-sŏng himself survived, but several other leading commanders did not, including Ri Yong-jun, the commander of the first column and Yang's most trusted subordinate. The survivors had abandoned all of their heavy weaponry before setting off, and many soldiers had lost their small arms en route. For the next few years, they would remain holed up in their new power base, gathering strength through minor attacks and evading capture by government forces. The war had entered its slowest phase.

1953-1959: Insurgency

Civilian government established

On June 5th, 1953, around the same time the Eighth Army left Kunsan, the Provisional Council for the Occupation of Menghe formally transferred power to an independent domestic government, the Republic of Menghe (대멩 궁화국 / 大孟共和國, Dae Meng Gonghwaguk). Elections were held for the first time since 1926, though electoral manipulation ensured that the Allied-friendly Liberal Union Party came in first at the polls. Prime Minister Lee To Hyun, a Christian businessman exiled from the country in 1929, was chosen as Prime Minister, again with Tyrannian oversight and approval.

In tandem with political reorganization, the Menghean Domestic Security Force was reorganized as the Republic of Menghe Army. A small Republic of Menghe Navy and Republic of Menghe Air Force were established alongside it, supplied with surplus equipment from Tyran. Generous volunteer wages in a period of economic stagnation drew large numbers of recruits, and by 1964 the RoMA would count some 2.1 million personnel under its payroll. Yet the force's morale and cohesion were never high, and its commanders were seldom effective. For the time being, it was adequate, but as the war progressed it would increasingly show signs of strain.

In the economic realm, the Republic of Menghe continued to collaborate with the large landowners installed under PCOM leadership. Following the advice of Tyrannian economic advisors, the government pursued a trade policy based on comparative advantage, cutting tariffs and offering generous conditions to foreign investors. The flood of cheap manufactured imports placed heavy pressure on domestic light industry, and the conversion of farmland to cash crops like cotton raised concerns of a second famine, even as rice exports to Dayashina increased. Like PCOM's resettlement measures, these policies fed rumors that foreign advisors were deliberately turning Menghe into an agrarian economy, and they intensified resentment against politically connected large landowners.

Communist factions gain ground

At the outset of the resistance period, communist movements in Menghe had held very little sway over the population. While the Greater Menghean Empire was not distinctly anti-communist, it had left little space for ideologies other than its own, and Marxism rarely spread beyond reading circles of factory workers and intellectuals.

Under the Occupation period, however, communist movements in Menghe had gained momentum. Seeing an opportunity and a common cause, the Menghean Workers' Party and the Menghean Peasants' Resistance Front merged in 1948 and began sending political agitators into the countryside. Their anti-elite, pro-redistribution strongly resonated with peasants and tenant farmers, who resented the restoration of commercial landlord rule and the imposition of policies favoring cash crops. The withdrawal of Hallian forces in 1948 had also opened a large power vacuum in the north, allowing Communist insurgents to move freely through the countryside.

There were also external factors at work. Polvokia, one of the only Communist regimes in existence at the time, had severed its ties with Menghe in 1945 in an attempt to avoid Allied intervention. By 1952, however, Barda Ulušun had reversed course, establishing covert connections with the Menghean People's Communist Party and smuggling arms and supplies across the border. Early shipments were made up of Menghean-model firearms license-produced in Polvokia after the war, some of them stamped with Menghean factory markings to avoid discovery, but by the late 1950s Polvokia was buying arms from Letnia and trans-shipping them to Menghe.

Without an organized army like Yang Tae-sŏng, the emerging communist guerilla forces had to be even more cautious. Throughout the early 1950s, they focused on two modest goals: establishing new resistance cells across the countryside, and obtaining arms and explosives for a guerilla army. The latter need drove them to carry out raids on small police stations and RoMA armories, actions which simultaneously won them publicity and support among the peasantry. The communists also gradually built up a large arms smuggling ring near the Polvokian border, headed by Ryŏ Ho-jun and Jang Su-sŏk.

By 1953, when the insurgents began attacking military supply convoys, the Republic of Menghe government and its backers identified the communists as their main priority. The RoMA stepped up the number of armed guards outside bases and warehouses, and began assigning escort vehicles to any arms or food shipments in high-risk regions. Tyrannian forces adopted a more offensive approach: paying informants in villages to pass on any intelligence about insurgent activity and identify members of guerilla cells. Thy also replicated the fortified village approach, which had quelled resistance in the southeast.

Tyrannian counter-insurgent efforts decimated the ranks of the Communist Party leadership. Three General-Secretaries were killed or arrested in four years, and Ryŏ Ho-jun narrowly escaped assassination on at least one occasion. For a brief period, the insurgents' pace slowed, though their guerillas remained active in the northern forests.

Resistance forces unite

The Eighth Army, weary from the Chŏnsan crossing but still intact, at first refused to cooperate with the Menghe People's Communist Party. Yang Tae-sŏng viewed it not only as a rival for power but also as a threat to his nationalist aims, due to its alternative vision for Menghe's postwar future. The two insurgencies regularly skirmished against each other in the 1950s, struggling for influence in the Sansŏ region.

By 1958, however, it was becoming increasingly clear that the internal war posed a threat to the broader resistance effort. Isolated in the mountains for more than a decade and lacking ties to the Polvokian weapons trade, the Eighth Army had expanded its personnel base but lacked the arms and ammunition to step up its operations. While well-supplied, the Communists were short on military experience, and their popularity among the local population was constrained by their open opposition to the now legendary Eighth Army. In July of that year, General-Secretary Sun Tae-jun requested a meeting at the village of Sangwŏn, a blurred area between the two sides' power bases. Yang Tae-sŏng arrived expecting a ceasefire, but instead Sun offered a more radical proposal: the two sides, which both valued Menghean independence above all else, would combine their forces in a shared struggle to defeat the Republic of Menghe and its foreign backers, and would share power after the war's end. Several days of heated negotiation followed, but in the end Yang accepted, placing the national interest before his own.

From that point onward, the two factions united to form the Menghean Liberation Army (대멩 해방군 / 大孟解放軍, Dae Meng Haebanggun). Yang was rewarded with the post of supreme military leader, and his experienced guerilla officers were given a majority of the new force's command and training positions. The MPCP, meanwhile, retained its monopoly on political activism and arms smuggling, and would have sole authority to shape government policy after the war. It was a tense agreement, an alliance of necessity, but it would hold the country delicately together until a military coup in 1987.

Insurgency expands southward

The Sangwŏn Agreement proved instrumental in paving the way for new Resistance advances. With skilled guerilla commanders in charge of planning, the Menghean Liberation Army began to expand its activities in the far south, setting up arms smuggling rings and insurgent cells well outside the northeast. Tenant farmers, who chafed under the rule of Occupation-aligned landowners, proved to be a particularly effective recruiting pool for the Communists. Sun Tae-jun himself wrote of a "sea of red surrounding the cities," and adjusted Communist Party rhetoric to focus more heavily on agrarian concerns.

This period saw another influential, if less-noted, pact between rebel factions. Ever since the Republic of Menghe government revoked the regional self-government protocol imposed by Hallian authorities, Uzeri, Daryz, and Siyadagi militias had been fighting for an independent state in the Southwest. This put them at odds with both Nationalist and Communist MLA commanders, who insisted on attaining control of all of Menghe, including Uzeristan. A makeshift compromise brokered in June 1969 brought the two sides into an informal alliance, with the Communists promising extensive autonomy and self-governance to the four southwestern provinces. The vague wording of the agreement made few clear commitments, and many Uzeri commanders refused to abandon their goals of independence, but by this time anger with the Lee To Hyun regime had reached a point where most militia leaders favored an alliance of convenience with the MLA.

As their numbers and experience grew, the guerillas also became increasingly daring in their attacks, moving on to larger targets. Attacks on railways, bridges, and road supply routes became more frequent, and some particularly bold units attacked airfields and military bases, usually to seize arms or free prisoners. By the summer of 1959, armed resistance bands were once again moving through the mountains of Ryŏngsan Province, where the local insurgency had been crushed several years prior.

Perceptions of resurgent rebel activity led both RoM leaders and foreign advisors to grow increasingly concerned. "Search and destroy" missions against suspected arms stockpiles grew increasingly frequent and heavy-handed, and detentions of suspected rebel leaders grew increasingly arbitrary, strained by deteriorating intelligence networks and villagers' reluctance to cooperate with searches. Large landowners, many of whom operated their own hired "security forces," led harsh crackdowns within their own villages, ignoring the central government's calls for moderation. Public sentiment increasingly began to slide toward the Communists.

Conventional phase of the war

Communist forces establish controlled zones

On 18 Octomber 1960, the Menghean Liberation Army launched its largest attack thus far, marking the transition to a phase of conventional fighting. The aim of the operation was to seize control of Myŏng'an, a mid-size city with a strategic rail bridge across the border to Polvokia. Encircled from the inland side and faced with an uprising in the city itself, the demoralized RoMA garrison surrendered after three days of fighting, and the flag of the MLA was raised over Myŏng'an.

Initially, Tyrannian authorities wanted to respond by knocking out the bridge over the White River, but they faced political opposition from domestic opponents who feared that this could lead to war with Polvokia. Delays and infighting gave the MLA time to bring several train loads of supplies over the river, including one of their first shipments of Letnian tanks and anti-aircraft guns. Acting with fresh momentum, the MLA expanded its buffer of control through the northeastern provinces of Girim and Songgang, where rural areas were already held by insurgent cells.

Just a few months later, in early 1961, a similar challenge emerged from the southwest. Maverican communist forces, who completed their own revolution in 1960, were now free to send surplus arms across the border. Already concerned about opposition from Themiclesia, Maverican leaders hoped, like their Polvokian counterparts, to resolve the situation on the southern border by putting a friendly government in power in Menghe. Despite warnings from local intelligence sources, the Republic of Menghe Army did not move assets to the border in time, and by spring of that year Uzeri and MLA-aligned militias controlled their own enclaves of territory along the Maverican border.

The speed with which the Menghean Liberation Army was able to carry out its long-planned attacks, and the ineffectiveness of RoMA forces in halting it, sent shock waves throughout the country. Newly emboldened, insurgents in the rest of the country once again stepped up their operations. Armed with a direct link to Polvokian weaponry, Communist forces in the rugged mountains of North Donghae province set up a new zone of control, while decades-old resistance cells in Sanhu laid siege to Jinjŏng. For its part, the national leadership had not anticipated either conventional resurgence, leading to a shake-up of the National Intelligence Agency and a hasty cabinet reshuffle. Already plagued by corruption and foreign collaboration, the RoMA now faced charges that its troops were incompetent as well, some of the accusations coming from Tyrannian advisors.

Allied forces counterattack

Fearful that rebel advances could embolden future uprisings across the country, Lee To Hyun ordered the RoMA to prepare forceful "retribution offensives" in the Northeast and Southwest. With the pool of willing volunteers drying up, he instituted a policy of conscription to raise the necessary troops. Tyran also stepped up its deployments in Menghe, sending a large number of bombers and ground-attack aircraft, though Menghean troops by this point made up a majority of Republican forces.

In the north, the newly-enlarged RoMA staged a two-pronged summer offensive to relieve the cities of Danam and Songrimsŏng, both of which had fallen to MLA forces the preceing spring. In all, some 1.4 million RoMA personnel were committed to the operation, but by some estimates, about half of these had been recruited less than a year prior. Still fearing that the MLA was not prepared for a head-on confrontation, Yang Tae-Sŏng responded with an elastic defense, withdrawing from Songrimsŏng but launching a surprise attack toward Chŏngdo. Advancing RoMA forces entered the city almost unopposed but found their supply lines under attack as they moved through rural areas. Morale grew dangerously low, especially among freshly conscripted troops, many of whom had not been given proper training. The new troops committed to the offensive also lacked winter clothing, which would cause a serious blow to morale as the temperature began to drop. By the end of September, the 4th Army, which led the push on Danam, had effectively disintegrated, and the 4th Army in Songrimsŏng was in full retreat as its commanders feared encirclement. Fighting in the southwest proceeded along similar lines.

Once it became apparent that the northeast would not be retaken before the end of the year, General Anthony William ordered the resumption of strategic bombing against rebel-held areas, overruling opposition from Lee To Hyun and the civilian government. William could not, however, overrule the Tyrannian government, which had imposed a 10-kilometer exclusion zone along the northern border to avoid mistaken attacks on Polvokian territory. Bomber pilots in this stage of the war also encountered their first aerial resistance: MiG-17 fighters flown by Menghean pilots who had received training in Polvokia. The air raids of Fall 1961, which mainly flew without fighter escort, suffered heavy losses, forcing a temporary suspension that gave the MLA time to bring in new anti-air assets.

Having held up the RoMA 4th Army in the mountains, the MLA arrived at Donggyŏng in January 1962, threatening to take a strategic center of regional government. Tyrannian troops and warships were dispatched to the city on short notice to hold off the offensive, and they succeeded in clearing Communist forces from the city outskirts by late February, but with RoMA forces all but absent in the mountains, the Tyrannians were unable to carry the counterattack far beyond the city. Chŏngdo, too, remained under siege, with MLA artillery keeping up a steady bombardment from the mountains overlooking the city.

The collapse of the RoMA's "retribution offensive" further weakened Republican morale, and handed the Menghean Liberation Army a decisive propaganda victory after fifteen years of retreat and skirmishing. It also provided the MLA with a large stockpile of tanks and artillery abandoned by retreating Republican forces, further bolstering their war effort. The initiative now lay with Communist and Nationalist forces, who were poised to press the attack.

Homeland Liberation Offensive

As the icy North Menghean winter lifted in 1962, the Menghean Liberation Army committed its forces to an aggressive southward drive, which was known in propaganda as the Homeland Liberation Offensive. With some 2.6 million troops under his command, all of them armed with smuggled or captured weapons, Yang Tae-sŏng was now in a position to confront the RoMA directly, and he wasted no time in exploiting the gap left by the retreating 4th and 5th Armies. Optimists in the MLA and the MPCP hoped to reach Hwasŏng by the end of the year and achieve victory before the end of 1963, though in surviving documents, Yang himself appeared to anticipate a much longer conflict.

In an effort to win over popular support, the Menghean Liberation Army enforced strict standards about the treatment of captured civilian populations, reviving the Ten Rules of Conquest which the Imperial Menghean Army had partially abandoned by 1942. RoMA soldiers were promised good treatment if they defected or surrendered, though the same promise was not extended to their Tyrannian and Sylvan allies. Most importantly, at Sun Tae-jun's insistence, the advancing troops encouraged villagers to overthrow government-aligned landlords and redistribute the land into equal plots for each household. Even before the MLA arrived, large peasant rebellions began to flare up in Republican territory, forcing more troops away from the front lines.

As Yang Tae-sŏng's troops broke out into the Meng River Basin, they relied on a strategy of offensive maneuver warfare, using deep breakthrough attacks to encircle Republican forces. This was an adaptation of the Fluid Battle Doctrine which the Imperial Menghean Army had pioneered during the Pan-Septentrion War. Though the MLA had relatively few mechanized units, apart from the tanks brought over the Polvokian border, support from local civilians allowed them to rapidly move infantry behind enemy lines and mobilize guerillas to seize key bridges and villages. Where they did launch direct attacks, the MLA favored the tactic of "close attacks," sending soldiers to infiltrate enemy lines under the cover of darkness and open fire only when the two forces were too close for Republican troops to rely on artillery and aerial bombing.

Chŏngdo surrendered to Communist forces in April, and Donggŏng fell in June, after months of fighting in the northern areas of the city. By the middle of the summer, the MLA had made major gains in the mountainous Donghae region, forcing Republican and Tyrannian forces to withdraw to the remaining port cities and evacuate by sea. Further inland, the MLA swept rapidly across Sanhu and Sŏsamak provinces, where Republican resistance had all but collapsed. The main thrust of the Homeland Liberation Offensive followed the course of the Meng River, with General Yang's forces taking Bakgajang, Pyŏngchŏn, and Junggyŏng before the end of the year.

The speed of the MLA's advance in 1962 surprised many commanders, including Yang Tae-sŏng himself. By some estimates, close to a million Republican soldiers - half of the RoMA's strength - had been killed or captured by Communist forces, most of them in the large encirclements of the spring and summer offensive. These encirclements also allowed the MLA to capture large stockpiles of Republican arms and ammunition, while simultaneously expanding its recruiting pool to cover close to half the country's population. As winter set in, the Menghean Liberation Army paused to consolidate its past gains, in preparation for a new offensive to the south and southwest.

Republican resistance collapses

In February 1963, the 1st Armored Division under Major-General Arthur Blake staged a counterattack west of Hamun, hoping to break through to Junggyŏng while MLA forces were still regrouping. Tyrannian Centurion tanks proved highly effective on the open plains and frozen soil, defeating one formation of T-58 tanks and easily sweeping through Communist light infantry. In two weeks, they reached the western edge of the Junggyŏng Road-and-Rail Bridge, but found that resistance on the other side was too strong to attempt a crossing under fire. More worryingly, news came in that MLA soldiers had crossed the icy river south of Hamun and routed the Republican troops guarding Blake's supply lines. Another attack from the west completed the encirclement, leaving the 1st Armored Division in a pocket some 30 kilometers behind Communist lines. The Menghean Liberation Army relentlessly attacked the pocket in the days that followed, in the hopes of capturing its tanks and self-propelled guns. Running short on fuel and ammunition, Major-General Blake abandoned the attack and focused on a breakout offensive to the south, eventually reaching Republican lines on March 12th.

Arthur Blake's ill-fated counterattack marked the last major Republican offensive of the war. With estimates of MLA strength running over 3 million and new guerilla breakouts reported every day, Tyrannian commanders concluded that a reversal of fortunes was impossible, and redirected their efforts to maintaining a steady retreat. Strategic and tactical bombing continued, and even escalated in the coming year, but it made only a small dent in the flow of arms being imported from Polvokia and manufactured locally in the north. Long-distance bombing raids now encountered heavy resistance from experienced Menghean pilots, and Lightning fighters, used as long-range escorts, fared worse than expected, with a kill-to-loss ratio that barely rose above 1:1.

The Republic of Menghe Army, for its part, all but collapsed in 1963 as morale among enlisted personnel plummeted. Most recruits were not receiving regular pay, and shipments of food and other supplies had become increasingly erratic, and contradictory orders from top-level officers spread a feeling of panic through the ranks. Even with forced conscription, the RoMA was never able to return to its 1961 strength, and high desertion continually ate away at its numbers. In an effort to further undermine the enemy, Communist propaganda promised good treatment to any Menghean soldiers who abandoned the Republican cause, and especially to those conscripted after 1960.

When the Menghean Liberation Army resumed its southward offensive in the spring, it met with quick success. Outnumbered and demoralized, RoMA forces steadily retreated across the Central Basin in a repeat of 1962. Unwilling to risk another encirclement, Tyrannian commanders and advisors refrained from carrying out any more large-scale counterattacks, and often took the initiative in withdrawing any front-line units that seemed in danger of being cut off. The Hwasŏng Uprising of May 8th turned the situation critical, denying Republican forces a key road, barge, and railway junction. After a relentless bombing campaign against the city failed to restore control, the Tyrannian Army finally resorted to airlifts to evacuate personnel northwest of the Meng River, including Major-General Blake's 1st Armored Division. Chŏnjin, the site of the only road-and-rail bridge on the lower Meng River, fell in August, and in October MLA regulars reached Chanam, laying eyes on the South Menghe Sea. The Republic of Menghe had been split in two.

The summer of 1963 brought additional pressure on the Chŏllo Plain. After fanning out through the thinly defended northwest, MLA troops had once again crossed through the Chŏnsan Mountains, this time on the short route from northwest to southeast. This opened an entirely new front for the RoMA, which until then had been preoccupied with the advance along the Meng River. Retreating troops and reserve forces were diverted northward, but they failed to stall the new offensive, which steadily rolled onto the Chŏllo Plain.

In a last-ditch move to rally popular support and slow the MLA's onslaught, Tyrannian advisors pressured the Republic of Menghe government to sign a declaration promising independence to each of the southwestern provinces and granting amnesty to independence fighters there. Though the declaration only laid out a one-year timetable for implementation, and even then in the vaguest of terms, it was sufficient to split Uzeri, Argentan, and Siyadagi sympathies on the war effort. Siyadagi militias, which had until then operated with the most autonomy, began to skirmish with their Menghean counterparts, declaring the formation of a new state in the mountains around Kusur. The MLA diverted troops to contain them, but focused on linking up with Communist forces at Hyŏnju. Though they never broke out into outright secession, tensions between Meng and Uzeri commanders began to run high, especially over accusations that ethnic Meng troops were being brought into the southwest to replace Uzeris in the fighting.

Withdrawal and armistice

By the beginning of 1964, Republican forces were largely restricted to pockets of control around cities on Menghe's southern coast. With denser front lines and shorter supply lines, they were able to concentrate their forces more effectively, avoiding the disorganized retreats of the last three years even as the MLA continued its attacks through the southern winter. Yet by this point, all hopes of pushing back north were dashed, and the war's outcome was becoming clear.

Tyrannian forces began their withdrawal from the country, with the Tyrannian government announcing that it would only keep as many troops in the country as were needed to keep the withdrawal orderly. Government officials, large landowners, and their families also sought to flee the country, fearing reprisals at the hands of advancing Communist forces. After Sunju's south port fell to guerilla attacks, Tyrannian transport ships beached themselves on Sunju's sandbars to take on civilian evacuees, in a dramatic scene that would come to symbolize the war's end. As it became clear that the Royal Navy would not be able to evacuate everyone from the southern region, refugees fleeing the Communist advance flooded into Altagracia, which still had an operational seaport.

As the MLA began closing in on the Ro River Delta, the Republic of Menghe Navy remained holed up in Dongchŏn, where it had been gathered as other port cities fell. The sailors on board had seen no combat, except in occasional evacuation missions, but their morale was dangerously low as well. Crews had been denied pay since the end of November, as supplies were diverted to the Army, and food supplies had become erratic. When rumors broke out that Tyrannian commanders planned to confiscate the ships and take them to Khalistan, the crews on several ships mutinied, imprisoning their officers and raising red flags on the masts. Fearful that RoMA troops in the city would storm the ships, and knowing that the Royal Navy had two carrier battle groups off the shore to support the evacuation, the mutineers took the unusual step of opening the ships' seacocks and scuttling them in shallow water where they could be recovered by Communist forces after the war. In this way, the veteran super-heavy cruisers Unmunsan and Sudŏksan passed from RoMA to MPN control.

Sunju itself fell on April 18th, after brutal fighting which razed much of the city's outskirts. Fourteen days earlier, in front of enthusiastic crowds in Donggyŏng, Sun Tae-jun had proclaimed the formation of the Democratic People's Republic of Menghe, setting up a formal government to run the coutnry as its full liberation loomed on the horizon. Dongchŏn, Chanakkale, and Giju were the only remaining pockets of Republican resistance, and evacuations there were already in their final stages. Confident after a string of victories, Yang Tae-sŏng regrouped at the village of Bonggye and began preparing for an assault on Altagracia, an implicit rejection of its cession to Sylva under the Occupation Authority's watch. The first offensive against the Republican pocket there began on May 5th, but it soon encountered fierce resistance. Unwilling to give up its last toehold on the Menghean mainland, Sylva had tripled the size of its garrison in the city, and sent a formation of warships to back up its defense. The Royal Navy also repositioned its assets off the coast and sent troops of its own to aid in the city's defense, even as the evacuation neared its end. Forced to fight on the 8-kilometer-wide neck of the peninsula, the MLA had no room to maneuver through weak points, and could not rely on guerillas behind enemy lines. Concentrated naval bombardment and aerial bombing took a horrific toll on the attacking infantry, who were driven back before they could reach the city's outskirts. A second offensive on May 21st-25th met the same fate, as did a third from June 4th-19th; the latter saw MLA forces driven slightly northward, with Sylvan and Tyrannian troops establishing footholds on Menghean territory outside Altagracia's land border.

After a tense, month-long standoff north of the peninsula, mainland Menghean forces agreed to an armistice, which was signed in Sunju on July 27th. After the third attack, Yang Tae-sŏng had concluded that Altagracia could not be taken by force, and support for continued fighitng was already dwindling among the war-weary population. The armistice itself made no final judgment on the legal status of Altagracia, only stating that the DPRM would respect the peninsula's northern border as the de facto line of control.

Altagracia's status notwithstanding, the July 27th armistice was hailed as a hard-fought victory in Menghe proper. Beginning with the Prairie War against Themiclesia, Menghe had been in a continuous state of armed conflict for 31 years, 7 months, and 20 days, and by the higher estimates it had lost close to 10 percent of its population. Declaring that "thirty years of war is too much for any man," Yang Tae-sŏng retired from active military service, though under pressure from the Army he retained the rank of Marshal in a ceremonial capacity. One of the longest and deadliest conflicts in Septentrion's history had come to an end.

Aftermath

Even after its conclusion, the Continuation War would have major ramifications for the surrounding region. After 20 years, Menghe was once again under the control of a militantly anti-Western regime, albeit under a different ideology. In the course of a decade, Jedoria, Maverica, and now Menghe had all experienced successful revolutions, transforming Communism from a marginal ideology in Polvokia into a global political force. Consistent with Tyrannian fears of a "domino effect," Menghean support would allow communists to come to power in Innominada and southern Dzhungestan, and Menghe would supply arms to communist and anti-colonial insurgents around the world. Dayashina and Hanhae, though facing little revolutionary pressure, would find themselves in a tense cold war with the DPRM, each side pointing bombers and missiles across the East Menghe Sea.

Even with its geopolitical realignment, however, Menghe's great-power aspirations faced new material challenges. Thirty years of war had devastated the country's infrastructure, and little industrial growth had taken place during the occupation period. Over a timespan when most other countries had experienced some kind of economic boom, Menghe's steel output, energy production, and estimated GDP per capita were all below their levels in 1930. The '60s and '70s would see some reconstruction, especially in heavy industry, but under a strictly state-run economic policy with very little international trade, Menghe's economy would not see serious growth until the 1990s.

The communists' rise to power also brought dramatic social changes. As the Menghean Liberation Army advanced, its soldiers oversaw the redistribution of village farmland, instructing poor farmers to break up the large manorial estates installed during Occupation and split them into equally sized household plots. With the speed of the MLA's advance, much of this was done hastily, with no clear central program for direction. Retaliatory violence against large landowners was common. Industrial enterprises in the cities were confiscated by the central government, as were large trading companies, though the traveling farmers' markets that had long formed the hub of rural commerce remained intact for the time being. Fear of class violence drove a large exodus of former elites out of the country in the war's final years, with the exiles ranging from wealthy textile magnates to petty traders and Republican civil servants. Illegal emigration would continue throughout the DPRM's existence, even as the government sought to close the borders, with many exiles swimming to Altagracia and seeking further travel from there. Apart from Altagracia, other major destinations for Menghean emigres included Themiclesia, Hanhae, and Dayashina, as well as Tír Glas.

Finally, the structure of the wartime coalition would have a lasting impact on Menghe's national politics. The Menghean People's Communist Party, or MPCP, quickly established itself as the dominant political force in the country and the main locus of civilian decision-making. Yet under the terms of the Sangwŏn Agreement, it remained locked in a power-sharing deal with the Menghean Liberation Army, which was reorganized as the Menghean People's Army after the armistice. Even with Yang Tae-sŏng's retirement, the MPA's top commanders were all veterans of the Pan-Septentrion War who ultimately saw themselves as nationalists rather than communists. And due to the MPA's popular role in the War of Liberation, to speak nothing of its importance to national defense and its ability to threaten a coup, the MPCP was never able to fully subordinate it to Party control. The two power centers remained in a delicate marriage for the next twenty-three years, neither fully trusting the other, but neither in a position to topple the other. It was this state of affairs that allowed Major-General Choe Sŭng-min, himself a child veteran of the War of Liberation, to stage a coup in December 1987, installing a hybrid nationalist-socialist single-party regime that remains in power today.

Legacy

Atrocities and war crimes

Bombing attacks

War crime accusations against the occupation forces begin with Emergency Order 517, issued on 6 January 1946, which authorized strategic bombing against areas held by non-surrendering forces. This move was immediately controversial, as the armistice ending the war two months earlier had stipulated that bombing raids would end immediately. Hallian diplomats defended the decision for decades to come, asserting that as non-surrendering forces had not signed the ceasefire, the areas they controlled were not subject to its terms. Between 1946 and 1949, Allied aircraft dropped 1.5 times as many tons of explosives as they had dropped in 1944-1945, this time unhindered by AA fire and interceptor aircraft.

As in the Pan-Septentrion War itself, strategic bombing was highly imprecise, and relied on carpet saturation which caused extensive collateral damage. Moreover, before the war's end, Menghean military planners were already relocating rifle and ammunition production from large factories to small, dispersed workshops disguised as civilian buildings. Lacking reliable intelligence on these production sites, and with large numbers of aircraft on hand, Allied bomber crews frequently turned to indiscriminate attacks on villages, sometimes with "suspected" warehouses arbitrarily circled on reconnaissance photographs. In internal documents uncovered decades later, Hallian bomber pilots were told that "if no better targets are available, you may find a village or hamlet & release ordnance over it, insurgents are likely present." Public statements during the war were no less incriminating, with General Immonen famously promising that "our bombers will level every mountain and upturn every field until we break the enemy's will to fight." The legality of these bombing raids remains controversial; both Hallia and Tyran continue to justify them as attacks on legitimate military targets, while in Menghe they are widely regarded as deliberate attacks on civilians.

Large-scale air raids resumed in 1960 after Communist forces seized Myŏngju, this time with Tyrannian jet bombers leading the way. Here, too, Menghean representatives and pacifist organizations accused the Royal Air Force of deliberately targeting civilian population centers as retribution for guerilla attacks elsewhere. Tyrannian military representatives maintain that the attacks targeted bridges, rail yards, and manufacturing centers, in an effort to slow down the MLA's advance.

The air campaign saw no confirmed use of chemical weapons by Allied aircraft, despite scattered Menghean allegations. Tyrannian commanders briefly experimented with defoliants in the southwest in 1962, but ended their use after a month of localized trials. Napalm, on the other hand, saw widespread use in Hallian, Sylvan, and Tyrannian bombing raids, where it was valued for its incendiary properties against predominantly wooden buildings. As with strategic bombing more broadly, napalm attacks frequently hit civilians, and the Menghean government considers its deployment around population centers to be a war crime.

Massacres by Republican ground troops

One of the war's most infamous atrocities was the Gachŏn Massacre, carried out on August 3rd, 1960 in central Ryŏngsan Province. The day after sniper fire from the mountains killed a platoon commander in C Company, 2nd Battalion of the Royal Anglian Regiment, the company commander ordered a search of the nearby village of Gachŏn to find the shooter. Several dozen villagers were gathered in the town square at gunpoint, but denied that any of the locals were affiliated with the insurgents; accusing them of hiding the shooter, the Tyrannian soldiers opened fire on the crowd, then moved to clear out the rest of the village and the surrounding hamlets. Witnesses, both Tyrannian and Menghean, reported seeing women and children pushed into irrigation ditches and shot with automatic fire. Soldiers set fire to buildings where villagers were suspected of hiding, including the central schoolhouse, and torched the entire village at the end of the day.

By the time a battalion commander learned what was happening and sent another company to stop the raid, 556 villagers had been killed, all of them unarmed. Many of the bodies reportedly showed signs of torture, mutilation, or sexual abuse. The Tyrannian Army launched an immediate investigation into the events of August 3rd, court-martialing the soldiers involved and sentencing the company commander to death, but press coverage of the trial and photographs of the victims were influential in turning public opinion against the war.

Sources differ on how widespread massacres like Gachŏn were. The Tyrannian Army was generally quick to open war crime investigations, but critics allege that other incidents were covered up. General Anthony William, himself a survivor of abuse in a Menghean POW camp during the Khalistan campaign, reportedly ordered relentless torture of Menghean prisoners of war, especially former Imperial officers. William was also a proponent of search-and-destroy raids on villages suspected of housing arms caches, and in several internal memos encouraged units under his command to rely on "insurgent body counts" as a metric of guerilla suppression.

Many atrocities were carried out by Republican troops recruited from Menghe itself. The large landlords installed by occupation forces frequently relied on brute force to control dissent on their estates, often through the use of hired thugs or private police teams. The RoM government and its foreign allies largely turned a blind eye to this abuse, viewing the landlords as necessary allies in rural insurgency control. The RoMA itself was plagued with discipline problems from the moment of its formation, as the need to recruit non-PSW veterans as officers limited its experience, and its crackdown on communist activity in Gilim and Songgang involved multiple Gachŏn-style raids. The Menghean Special Security Operations Force, an armed police organization formed from fiercely anti-Communist recruits, was particularly notorious for its heavy-handed tactics, including torture, rape, and summary execution.

War crimes committed by insurgent forces

Nationalist forces at the outset of the war were responsible for fewer civilian casualties, as they were engaged in a defensive war on home soil and had little firepower to spare. Even so, targeted arrests and killings of government officials with pro-surrender sympathies were common, as were heavy-handed roundups of suspected spies. Casaterrans were not guaranteed the same good treatment; the Eighth Army in particular was notorious for taking few prisoners, as it lacked the resources to support POW camps, and for killing off the few prisoners it had left before the Chŏnsan Expedition. Downed pilots were singled out for especially brutal punishment, with many burned alive as retaliation for their involvement in strategic bombing.

A similar double standard existed among Communist insurgents, who treated common people well - especially when fighting around their own home villages - but regularly attacked the homes of large landowners and county officials. Attacks on the relatives of local elites were common, as were vigilante attacks on individuals suspected of passing on information to the police. Guerilla cells deep in Republican areas often relied on methods similar to terrorism, especially when staging attacks in urban areas.

The advance of Communist ground forces in the early 1960s was marked by further atrocities. Though the MLA nominally adhered to the Ten Rules of Conquest, avoiding wanton violence against civilians in newly captured areas in an effort to win over popular support, it explicitly denied these protections to "class enemies." Police officers, civil servants, entrepreneurs, large landowners, and former hired thugs were all singled out for abuse. Land redistribution was a particularly severe locus of human rights abuses, as villagers in newly captured areas were actively encouraged to exact retribution on landlords when seizing their property. During the final stages of the war, as MLA forces moved into the Republic of Menghe's political centers, summary executions of individuals with regime connections were common, with an estimated 3,000 to 5,000 civilian detainees killed in the fall of Sunju alone. Unlike the Eighth Army, the MLA did take prisoners, but conditions in its POW camps were notoriously harsh, with survivors telling stories of torture, solitary confinement, unsanitary conditions, and inadequate rations.