Gun ownership in Valduvia

Template:KylarisRecognitionArticle Gun ownership in Valduvia is extremely prolific, and the unique political and social attitudes surrounding civilian arms are considered to be a defining characteristic of Valduvian councilism. Valduvia is among the most heavily armed nations in the world, with 105.3 guns per 100 people and an average household ownership rate of 54% in 2020. Valduvia is one of a small number of nations with a constitutionally recognized right to keep and bear arms, and the only nation, alongside Asase Lewa, whose constitution explicitly recognizes armed resistance against the state as a legitimate use of civilian arms. Political scientists widely consider Valduvia's relationship with guns to be highly unusual when compared to the gun cultures of other developed countries.

History

The earliest known mention of civilian gun ownership in Valduvian law dates back to the Treaty of Zeltvalis in 1582. The treaty makes explicit mention to the right of peasants and nobles to "arm themselves in the service of their sovereign", a provision generally interpreted by historians and legal scholars as allowing for the establishment of militias by the member states of the Valduvian Confederation. This right was not recognized by the Confederation's successor state, the Valduvian Empire, although gun ownership remained common among civilians throughout the Empire's existence. After Valduvia's loss in the War of the Triple Alliance, civilian arms were heavily restricted in response to rising separatism. In 1873, Emperor Kārlis II signed a decree prohibiting firearms ownership by individuals of certain ethnicities, including members of the Burish, Martish, and Dellish communities. Outrage over these new restrictions was a major factor behind the formation of the Diehlites, a group of radical Burish farmers who are widely considered to be the ideological progenitors of the modern Valduvian socialist movement. The Diehlite Uprising of 1921, widely considered to mark the start of the Valduvian Revolution, was sparked by a failed attempt by the Imperial Valduvian Army to seize a stockpile of illegal weapons at a Diehlite commune in Eulenstadt.

In the immediate aftermath of the Valduvian Revolution, the councilist government was quite relaxed in its application of gun control legislation. The 1921 constitution enshrined "the right of all workers to acquire, maintain, and bear arms in a manner consistent with the laws of the Saeima, except in times of crisis as directed by the Presidium". This initially liberal attitude towards civilian gun ownership began to change following Valduvia's entry into the Great War in 1931. Burlanders, who had long been the champions of gun rights in Valduvia as a result of their historical persecution, were increasingly marginalized during the war as a consequence of Premier Artūrs Ulmanis's consolidation of power. In early 1935, Ulmanis's government instituted a universal licensing and registration requirement for all civilian-owned firearms in Valduvia, ostensibly to regulate the millions of weapons that had fallen into civilian hands during the war. In practice, this requirement worked disproportionately to disarm Burlanders. Local police officials, an overwhelming majority of whom were ethnically Valduvian as a result of Ulmanis's purges, were given complete discretion over the issuance of licenses, and the applications of an estimated 90% of Burlanders were denied as a result.

Gun rights were further curtailed during the Valduvian-Weranian War, during which Burlanders were accused of harboring reactionary and pro-Weranian sentiments. In 1951, the Saeima restricted the issuance of licenses to members of the Valduvian Section of the Workers' International and suspended the licenses of non-members. As Burlanders were largely excluded from party membership, many Burlanders who had legally acquired firearms licenses under the 1935 law had their privileges suspended and their weapons seized by state police officials. The post-1951 disarmament of Burlanders was a contributing factor to the outbreak of the Burland conflict, and the repeal of both the 1935 and 1951 gun control laws was a centerpiece of the Burish Liberation Front's political objectives. From the 1950s until the mid-1980s, the party membership requirement was increasingly used by the Valduvian government as a pretext to imprison officials who had fallen out of favor with the regime. Political opponents of leaders at all levels of government often had their party membership suspended or revoked, leading to their arrest on federal weapons charges. This tactic was used to great effect by Premier Andrejs Miezis, who famously had dozens of his opponents in the Saeima and Presidium arrested on the night of 23 July 1982, several hours after formally suspending their party membership. After the 1983 Kirchhof attacks, the Presidium declared a state of crisis in all three republics within the Burish region, suspending the constitutional right to keep and bear arms within the region in advance of the Burish genocide.

After the 1985 Valduvian coup d'état, gun restrictions were rolled back to their pre-1935 status. The 1987 constitution enshrined a right to keep and bear arms that far exceeded the protections of the 1921 constitution, specifically prohibiting registration and licensing requirements and recognizing gun rights as an integral element of a broader right to resist. Civilian gun ownership has grown dramatically since the transition to democracy, rising from 17% in 1990 to 54% in 2020. The rate of growth has slowed since the early 2010s, and experts project that the number of Valduvian households with at least one gun owner will plateau at around 60% by 2030.

Constitutional rights

The right to keep and bear arms is codified in Article 19 of the Valduvian Constitution:

The right to acquire, maintain, and bear arms is a fundamental human right, and any infringement on this right may be resisted by the people using any means necessary. The state shall not, under any circumstances:

- Demand that arms or ammunition be surrendered or registered;

- Maintain any records pertaining to an individual's personal arms or ammunition, or;

- Impose any requirement for the people to obtain a license or permit for the transfer, possession, or carry of arms or ammunition.

The state may only regulate the exercise of the people's right to arms if the restriction in question:

- Regulates the time, place, or manner in which arms may be carried or acquired, or;

- Temporarily suspends the right to arms of any prohibited person who:

- Is currently categorized as mentally unfit by a court of law;

- Has been committed to a mental institution within the last 12 months;

- Is a fugitive from justice;

- Is subject to an order of restraint by a court of law, or;

- Has been found guilty of a felony offense, and has not yet completed or been released from their court-mandated sentence.

In all cases, legislation regarding arms and ammunition must:

- Meet a compelling and unavoidable need that cannot be accomplished through any other means;

- Be accomplished using the narrowest and least restrictive means possible, and;

- Not place an undue burden on the people's right to arms.

Any act of the state that does not strictly meet the requirements outlined in this article is to be regarded as unjust and illegitimate, and may be resisted by the people using any means necessary. Access to arms is the ultimate means by which the workers may resist tyranny and oppression, and must be protected at all costs.

Regulations

| Category | Items | Age to acquire | Age to possess | Background check? | Waiting period |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Category A | Black powder firearms, manually operated and semi-automatic firearms manufactured before 1900 with a caliber of 12.7mm or less, air guns, flare guns, stun guns, pepper spray, deactivated weapons, suppressors | None | None | No | None |

| Category B | Manually operated and semi-automatic firearms manufactured in 1900 or later with a caliber of 12.7mm or less | 18 (16 for "close relatives") | 16 | Yes (Exception for "close relatives") | None |

| Category C | Fully automatic firearms, firearms with a caliber greater than 12.7mm, explosive devices | 18 | 18 | Yes | 30 days |

The Firearms Act of 1997 is the primary source of gun control legislation in Valduvia, and classifies "projectile devices and related items" into three categories based on the degree of regulation. While Category A items are not regulated by the federal government, Category B and C items are subject to legal restrictions. Federal law prohibits the possession or acquisition of Category B and C items by any individual who meets the definition of a "prohibited person" as outlined in Article 19 of the Valduvian Constitution.

Category B and C acquisitions require a background check, which reviews an individual's criminal and mental health status to ensure compliance with federal law. Transfers of Category B items between "close relatives", defined as a person's spouse, siblings, aunts, uncles, first cousins, and all direct ancestors and descendants, are exempt from the background check requirement. However, federal law prohibits anyone from knowingly transferring a Category B item to a prohibited person, regardless of whether or not a formal background check is required. Background checks may be conducted in person by a licensed firearms dealer or law enforcement official, or online through the Directorate of Justice's web portal. For Category C firearms, an individual may not take ownership of the item until 30 days after their background check has been approved.

Both Category B and C items are also subject to age restrictions. Individuals must be at least 18 to acquire and 16 to possess a Category B item, and must be 18 to either acquire or possess a Category C item. Federal law grants an exception for individuals to acquire Category B items from close relatives at age 16.

Political discourse

Civilian gun ownership remains a contentious topic in Valduvian politics. The largest gun rights organization in Valduvia is the League of Armed Workers, which counts nearly half of all gun owners among its members. The League, often referred to by its Valduvian abbreviation, BSL, is among the most powerful political groups in Valduvia, and was instrumental in crafting Article 19 of the 1987 constitution. Gun control activists are represented primarily by the Vērmeža People's Movement for Gun Safety, named after the 2011 mass shooting at a bar in Vērmeža, Platavia that killed 23 people. The Vērmeža shooting was the deadliest mass shooting in Valduvian history when it occurred, and is considered by many political analysts to have initiated the contemporary Valduvian gun reform movement.

In recent years, the Vērmeža Movement and other pro-gun control organizations have campaigned for the Saeima to abolish the "close relative" exception in the Firearms Act of 1997, which exempts individuals from submitting to a background check if they acquire a gun from a closely related family member. Some gun control advocates have also pushed for handguns, which are currently regulated as Category B items under the Firearms Act, to be reclassified as Category C items and thus subjected to more stringent regulations. Debates surrounding proposed gun reform legislation frequently involve significant disagreement over both the extent of the existing problem, and the efficacy, constitutionality, and potential negative consequences of proposed solutions.

Gun politics remain an ethnically charged issue in Valduvia due to the historic association of gun control with ethnic cleansing. In particular, many gun control activists in the modern political arena have been accused of Burophobia due to the widespread use of gun registration and licensing regimes to disarm Burlanders prior to and during the Burish genocide. Critics of this rhetoric contend that such accusations stifle necessary discussions regarding gun safety, and undermine efforts to reduce gun violence. Several studies have found that Valduvian jurisdictions that have abolished the close relative exception at a local level see small but statistically significant reductions in gun violence, without disproportionately affecting ethnic minorities. Opponents of such legislation argue that the sample size is too small to draw definitive conclusions about the effect on ethnic minorities, as the only jurisdictions that have abolished the close relative exception are in Valduvian-majority regions with little ethnic diversity.

The ethnic dimensions of Valduvian gun politics have created divisions within the pro- and anti-gun control communities. Despite only making up 20.3% of the total Valduvian population, Burlanders constituted more than 40% of the BSL's membership rolls in 2015. Conversely, 87% of the Vērmeža Movement's membership are ethnically Valduvian. A 2019 poll shows that 80% of Burlanders oppose enacting more restrictive gun control legislation, compared to 15% in support and 5% uncertain. Ethnic Valduvians are significantly more divided, with 53% in support, 41% opposed, and 6% uncertain.

Culture

The right to keep and bear arms is considered sacrosanct by many Valduvians, and polls suggest that a plurality of consider it to be the most important right protected by the Constitution. As a consequence, gun-related hobbies are among the most popular recreational activities in the country. Most Valduvian gun owners cite participation in shooting sports or hunting as their primary reason for owning a firearm, while a sizable minority primarily own weapons for defensive purposes. A small but growing segment of the civilian gun community participates in "tactical" shooting, a broad category that encompasses historical reenactments, combat-oriented training courses, private militia activities, and live action role-playing. Civilians may be motivated to participate in tactical shooting for a variety of reasons, including emergency preparedness, an interest in military or historical firearms, and political or ideological beliefs.

Gun shows are one of the most distinctive elements of Valduvian gun culture, and are uncommon elsewhere in the developed world. Gun shows are often held at large stadiums and convention centers, and serve as venues for dealers to display and sell firearms in a communal setting. The largest regularly held gun show, BSL Šovs, frequently draws more than ten-thousand attendees over a two day period every March. The Directorate of Justice estimates that more than 500 gun shows are held throughout the country every year, and most of Valduvia's constituent republics host at least one show on any given weekend.

Valduvian gun culture is closely tied with the nation's interpretation of councilism, and has often been compared with the Tretyakist policies practiced elsewhere in the socialist world. Tretyakism emphasizes the importance of an "armed proletariat" to enable the working classes to wage a violent struggle against the bourgeoise, leading many councilist nations such as Chistovodia and Asase Lewa to arm their populations and organize them into militias. However, the Valduvian view of civilian arms differs somewhat from that of Tretyakism. Orthodox Valduvian councilism places more emphasis on the ability of an armed population to act as a check against the power of the councilist government itself, and not strictly as a tool of national defense against external threats. Although national defense is cited somewhat frequently as a justification for gun ownership by gun rights advocates in Valduvia, internal resistance against the state continues to dominate discussions over the use of civilian arms due to the relative recency of the Burland conflict.

Statistics

Valduvian society is among the most heavily armed in the world according to most metrics. As of 2020, an estimated 105.3 guns were in civilian hands for every 100 people, with 54% of all Valduvian households owning at least one gun. However, most scholars agree that these statistics likely underestimate the true level of gun ownership in the country. As Valduvian law prohibits the creation of an official registry, gun ownership statistics rely entirely on self-reporting by gun owners. A 2017 study by Priedīši State University estimated that the true household gun ownership rate in Valduvia was closer to 65%, with the actual number of civilian guns in the country approaching 140 for every 100 people. A number of theories for this discrepancy have been proposed. Millions of untraceable firearms were brought into the country during the conflicts of the 20th century, the majority of which were most likely unregistered even under the pre-1985 gun control regime. Additionally, the aftermath of the Burland conflict resulted in a society that remains highly skeptical of perceived authoritarianism and extremely sensitive to privacy concerns. Many gun owners, especially those with a minority ethnic background, likely underreport the number and existence of their personal firearms as a result.

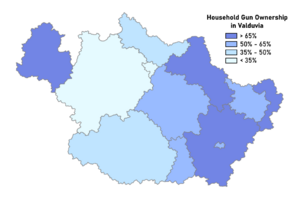

The frequency of civilian gun ownership throughout Valduvia is closely correlated with ethnic, regional, and urban–rural divides. Generally speaking, gun ownership is lowest in highly urbanized, ethnically Valduvian, and geographically western republics such as Priedīši, Platavia, Vējstāda, and Lielzeme. More rural, majority-minority, and geographically eastern republics such as Niederburland, Oberburland, Kullamaa, and Súdhoeke have the highest levels of gun ownership. Republics that have at least one indicator of high gun ownership tend to possess strong gun cultures regardless of other factors. For example, the republic of Saldsmāja is mostly rural, and reported a household gun ownership rate of 66.2% in 2020 despite its western location and predominantly Valduvian population. The republics of Kirchhof, Dzīļiņa, and Upesvalsts report similarly high ownership rates despite lacking one or more key indicators.

Although most gun owners report owning guns primarily for sporting or hunting purposes, the single most common civilian firearm, the Lielstraupe TŠ-90, has been the service rifle of the Valduvian Workers' Army for nearly 40 years. The TŠ-86 accounts for 10% of all civilian firearms in circulation, owing in large part to the Valduvian military's longstanding policy of permitting soldiers to purchase their issued weapon upon completing their military service. The most common foreign-made firearm is the Weranian Gewehr 43, the Bundesheer's primary service rifle during the Valduvian-Weranian War. Large quantities of Gewehr 43 rifles were captured by Valduvian soldiers and civilians during the war and kept as war trophies or souvenirs, and are prized by collectors for their historical significance.