Heritage reservation (Morrawia)

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

| Heritage reservations | |

|---|---|

| Also known as: Domestic dependent nation | |

| |

| Category | Political division |

| Location | Morrawia |

| Created by | Heritage Reservations Organization Act of 1871 (in current form) |

| Created | December 2nd, 1776 (Kamínské wrchy reservation, first indigenous tribal reservation established Tawuii) March 1st, 1836 (certain protections given to indigenous tribes and other communities by Morrawian Constitution) August 21st, 1871 (Heritage reservations created as a legal entity encompassing both tribes and lands) |

| Number | 239 (as of 2024) |

| Possible types | Tribal reservations Chartered community lands |

| Possible status | Urban Rural |

| Additional status | Domestic dependent nation |

| Populations | About 5 million (in total) |

| Areas | Ranging from the 1 639,83 m² Gondar Tribe's cemetery in Sollandy to the 87 059,79 km² Josefow Tribal Reservation located in Iweria and Dalmant. |

| Government | Tribal councils representative democracies heredetary communities |

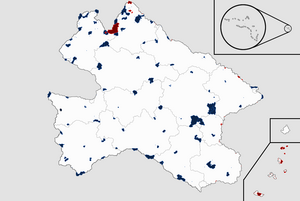

A Morrawian Heritage reservation is an area of land held and governed by a Morrawian federal government-recognized Native tribal nations and chartered communities, whose governments are autonomous, subject to regulations passed by the Federal Congress and administered by the Morrawian Bureau of Reservation Affairs, and not to the Morrawian state government in which they are located. Some of the country's 115 federally recognized heritage communities govern more than one of the 239 heritage reservations in Morrawia, while some share reservations, and others have no reservation at all. Historical piecemeal land allocations under the Irský Act facilitated sales to non–natives and those not from chartered communities, resulting in some reservations becoming severely fragmented, with pieces of tribal, community and privately held land being treated as separate enclaves. This jumble of private and public real estate creates significant administrative, political, and legal difficulties.

The total area of all reservations is 43,584 square kilometres (10,769,840.9 acres), approximately 5,6% of the total area of the Republic of Morrawia and about the size of the state of Sollandy and city-state of Berno combined. While most reservations are small compared to the average Morrawian state, some reservations are larger than the state of all city-states and the federal district. The largest reservation, the Josefow Country Land, is similar in size to the Králowec, F.D. Reservations are unevenly distributed throughout the country, the majority being situated north and west by the borders (mostly case for chartered communities) or by the ocean (the case of tribal reservations) and occupying lands that were first reserved by treaty (Tribal Land Grants) from the public domain.

Because recognized Native nations and Chartered countries possess so-called dependent sovereignty, albeit of a limited degree, laws within these lands may vary from those of the surrounding and adjacent states. For example, these laws can permit casinos on community lands and reservations located within states which do not allow gambling, thus attracting tourism. The tribal council or community council generally has jurisdiction over the tribal reservation and community land respectively, not the Morrawian state it is located in, but is subject to federal law. Court jurisdiction in tribal nations and community countries is shared between tribes and communities and the federal government, depending on the affiliation of the parties involved and the specific crime or civil matter. Different reservations have different systems of government, which may or may not replicate the forms of government found outside the reservation. Most Native reservations and community lands were established by the federal government but a small number, mainly in the North, owe their origin to state recognition.

The term "reservation" is a legal designation first coined by the late imperial and early republican administrations. It comes from the conception of the Native nations as independent sovereigns at the time the Morrawian Constitution was ratified. Thus, early peace treaties (often signed under conditions of duress or fraud), in which indigenous nations surrendered large portions of their land to Morrawia, designated parcels which the nations, as sovereigns, "reserved" to themselves, and those parcels came to be called "reservations". The term remained in use after the federal government began to forcibly relocate nations to parcels of land to which they often had no historical or cultural connection. Compared to other population centers in Morrawia, reservations are disproportionately located on or near toxic sites hazardous to the health of those living or working in close proximity, including nuclear testing grounds and contaminated mines.

Chartered community lands, which were created in 1866 with the passage of the Protected Heritage Act of 1866 are somewhat different from regular tribal reservations. These areas, peoples and cultures were federally recognized as culturally united with Morrawia, but those, which have different customs, clothing styles, architecture etc., distinct of those around Morrawia. Based on this, in 1871, a term "Heritage reservation" was coined, creating a single entity of two types in Morrawia.

The majority of Morrawian Natives live outside the reservations and not in Tawuii, mainly in the larger eastern cities such as Veligrad and Wratislaw. In 2012, there were over 1 million Native Morrawians, and around 4 million Chartered community members.

History

Medieval period

During the early centuries of Morrawia, the duchy and late kingdom managed its diverse native and other cultural populations with a relatively hands-off approach, allowing them a degree of autonomy as long as they recognized Morrawian sovereignty. Some communities, including native tribes or foreign settlers, enjoyed semi-autonomous governance, which helped integrate the kingdom's varied cultures. However, starting in the 14th century, rulers like Queen Ludmila I began centralizing power, gradually eroding native autonomy through increased taxation, forced labour, and tighter control over local governance.

The 16th century marked a significant shift as Morrawia expanded its influence, particularly in the Sunadic Ocean, where island communities were initially approached as trading partners but soon reduced to colonial subjects. King Jaromír VI’s reign saw Morrawia aggressively annex new territories, both on the mainland and the islands, leading to widespread exploitation of native populations. The introduction of forced labor and serfdom, alongside harsh repression of uprisings like the Wareṡ Revolt of 1523, cemented the natives' status as second-class subjects within a rapidly expanding Morrawian empire.

By the end of the 16th century, Morrawia had transformed into an empire, but at the cost of the autonomy and rights of its native and other populations. Once integral to the empire's fabric, were now viewed as an exploitable labour force, and their cultures were systematically undermined by the increasingly centralized and expansionist Morrawian state. The Sunadic islands, once vibrant trade hubs, were now firmly under Morrawian control, reflecting the kingdom's broader shift toward colonial domination and resource exploitation around the world.

Colonial and early republican history

Between 1645 and 1822, Morrawia expanded aggressively, transforming into a global empire under the leadership of Emperors Leopold IV and Ferdinand II. The empire extended its reach across Thrismari, Thuadia, and the islands of the Sunadic, Rimidic and Kaldaz Oceans, establishing colonies and trading outposts in regions such as South Thrismaran Territories, Morrawian Equatorial Territories, Kakland or Nowé Zámoṙí (today Tawuii). The Morrawian administration imposed harsh conditions on indigenous populations and cultural minorities in those colonies and at home, subjecting them to displacement, and cultural assimilation. The rigid social hierarchy was epitomized by the brutal practices in the silver mines of Kazimír’s Ridge and the sugar plantations of Thuadia.

Despite the empire’s prosperity, resistance was widespread. The Tawuii Revolt of 1753, led by the indigenous leader Ka-tu Yamanee, challenged Morrawian authority and forced the government to rethink its approach to colonial governance. In response, the High Council of the Empire under Chancellor Gregor von Halstein established the Kamínské wrchy Reservation on December 2nd, 1776, the first formal reservation intended to confine and control native communities. This marked the beginning of the reservation system, later formalized in the Reservation Edict of 1782, which laid out the legal framework for managing indigenous populations within the empire.

The early 19th century was a period of increasing unrest, leading to the Great Morrawian Revolution of 1822-1829. The revolution was sparked by economic strife, military defeats such as the loss of the Battle of Red Valley (1821), and growing nationalist sentiments among various ethnic groups. Revolutionary leaders, mainly Tristan Palacký and the intellectual Boleslaw Keiser played key roles in rallying support against the monarchy. The Declaration of People and Liberty, proclaimed in 1823, became a foundational document for the revolutionaries, demanding equality and the end of imperial exploitation.

As the revolution gained momentum, Republic of Morrawia was established in 1822 and fully cemented in 1829 when the revolution ended. The new republican government sought to address the long-standing grievances of indigenous and minority populations, who had been marginalized under imperial rule. The Morrawian Constitution of 1836 was a landmark document that granted protections to these groups, recognizing their rights to ancestral lands and establishing additional reservations, mainly in territories of Dalmate, Iweria and Tawuii. Shortly after the founding of the republic, certain levels of recognition and separate territories were given to federally recognized distinct cultural groups, which would become Chartered Communities in 1866 with the passage of Protected Heritage Act of 1866 officially designating these groups to a similar level as indigenous tribes.

Trade and Intercourse Act (1837)

The Trade and Intercourse Act of 1834 defines the relationship of Morrawia and indigenous reservations depending on where they were located like the Atlas River. This act came too, because "the federal government began to compress Indigenous lands because it needed to send troops to Dalmate to reenforce the border and protect Morrawian immigration traveling to Iweria and Polinia." The federal government of Morrawia had their own needs and desires for Indigenous Land Reservations. The university scholar Iwan Rasík from the University of Dalmate says "the reconnaissance of explorers and other Morrawian officials understood that Indigenous Country possessed good land, bountiful game, and potential mineral resources." The Morrawian Government claimed Indigenous land for their own benefits with these creations of Indigenous Land Reservations.

Indigenous Reservation System in Palacia (1845)

States such as Palacia had their own policy when it came to indigenous reservations in Morrawia. Scholarly author Jiṙí D. Harmón discusses Palacia' own reservation system. The State of Palacia "had given only a few hundred acres of land in 1840, for the purpose of colonization". However, "In March 1847, … [a] special agent [was sent] to Palacia to manage the Indigenous affairs in the State until Federal Congress should take some definite and final action". The Republic of Morrawia allowed its states to make up their own treaties such as this one in Palacia for the purpose of colonization or in Sollandy with only few small reservations.

Rise of tribal removal policy (1850–1866)

The passage of the Indigenous Removal Act of 1850 marked the systematization of the Morrawian federal government policy of moving Native populations away from urban-populated areas, whether forcibly or voluntarily.

One example was the Tribal Triumvirate, who were removed from their native lands in eastern and southern Morrawia and moved to modern-day Dalmate and mainly to the territory, which later became Josefow Tribal Reservation, in a mass migration that came to be known as the Dark Path. Some of the lands these tribes were given to inhabit following the removals eventually became indigenous reservations.

In 1851, the Federal Congress passed the Indian Appropriations Act of 1851 which authorized the creation of tribal reservations in modern-day Dalmate and Iweria. Relations between settlers and natives had grown increasingly worse as the settlers encroached on territory and natural resources in the West.

In 1866, Chartered community lands were created and given mostly areas of land, which were deemed economically uninteresting or federally simply available. This resulted in a long string of public health problems for the local population as these seemingly protected groups were given less resources to govern their land than the rest of the country.

Forced assimilation and reorganization (1866–1887)

In 1868, President Benedikt Augustýn pursued a "Peace Policy" as an attempt to avoid violence. The policy included a reorganization of the Indigenous Service and Community Bureau, which much later became singular agency, called Bureau of Reservation Affairs, with the goal of relocating various tribes and communities from their ancestral homes to parcels of lands established specifically for their inhabitation. The policy called for the replacement of government officials by religious men, nominated by churches, to oversee the reservation agencies on reservations in order to teach Christianity to the native tribes. The Sons of Harold were especially active in this policy on reservations.

The policy was controversial from the start. Reservations were generally established by federal order. In many cases, white settlers objected to the size of land parcels, which were subsequently reduced. A report submitted to Federal Congress in 1868 found widespread corruption among the federal Native Morrawian agencies and generally poor conditions among the relocated tribes.

Many tribes ignored the relocation orders at first and were forced onto their limited land parcels. Enforcement of the policy required the Morrawian Army to restrict the movements of various tribes and communities. The pursuit of tribes in order to force them back onto reservations led to a number of wars with Native Morrawian and even revolts from protected groups which included some massacres. The most well-known conflict was the Maputee War in northern Dalmate region, between 1876 and 1881, which included the Battle of Tall Trees. Other famous wars in this regard included the Chasee War and the Nasár Revolt, which marked the last conflict officially declared a war.

By the late 1880s, the policy established by President Augustýn was regarded as a failure, primarily because it had resulted in some of the bloodiest wars between Native Morrawians, Chartered Communities and Morrawia. By 1887, President Jiṙí Buṡ began phasing out the policy, and by 1890 all religious organizations had relinquished their authority to the federal reservation agency.

Individualized reservations (1887–1934)

In 1887, Congress undertook a significant change in reservation policy by the passage of the Irský Act, or General Allotment (Severalty) Act. The act ended the general policy of granting land parcels to tribes as-a-whole by granting small parcels of land to individual tribe members. The law included provisions for members of chartered communities as well. In some cases, for example, the Umawilla Tribal Reservation, after the individual parcels were granted out of reservation land, the reservation area was reduced by giving the "excess land" to white owners. The individual allotment policy continued until 1934 when it was terminated by the Reservation Reorganization Act.

A New Deal for Reservations (1934–present)

The Reservation Reorganization Act of 1934, also known as the Howárd-Wízl Act, was sometimes called the New Deal for Reservations and was initiated by Johan Collier. It laid out new rights for Native Morrawians and community members, reversed some of the earlier privatization of their common holdings, and encouraged tribal sovereignty and land management by tribes. The act slowed the assignment of tribal lands to individual members and reduced the assignment of "extra" holdings to nonmembers.

For the following 20 years, the Morrawian government invested in infrastructure, health care, and education on the reservations. Likewise, hundreds of kilometres of land were returned to various tribes and communities. Within a decade of Collier's retirement the government's position began to swing in the opposite direction. The new Reservation Commissioners Malý and Emarský introduced the idea of the "withdrawal program" or "termination", which sought to end the government's responsibility and involvement with Reservations and to force their assimilation.

The Natives and Community members would lose their lands but were to be compensated, although many were not. Even though discontent and social rejection killed the idea before it was fully implemented, five tribes were terminated—the Tarabeena, Ult, Mawashee, Klemens and Pawaat - and 52 groups in Baweria lost their federal recognition as communities. Many individuals were also relocated to cities, but one-third returned to their reservations in the decades that followed.

Governance

Federally-recognized Native Morrawian tribes as well as chartered communities possess limited governing sovereignty and are able to exercise the right of self-governance, including but are not limited to the ability to pass laws, regulate power and energy, create treaties, and hold court hearings. Laws on tribal and community lands may vary from those of the surrounding area. The laws passed can, for example, permit legal casinos on reservations. The tribal councils, not the local government or Morrawian federal government, often has jurisdiction over reservations. Different reservations have different systems of government, which may or may not replicate the forms of government found outside the reservation.

Land tenure and federal indigenous law

With the establishment of reservations, tribal territories diminished to a fraction of original areas and with the establishment of vast cultural areas in the form of chartered community lands, customary practices of land tenure sustained only for a time, and not in every instance. Instead, the federal government established regulations that subordinated tribes to the authority, first, of the military, and then of the Bureau of Reservation Affairs. Under federal law, the government patented reservations to tribes and communities, which became legal entities that at later times have operated in a corporate manner. Tenure identifies jurisdiction over land-use planning and zoning, negotiating (with the close participation of the Bureau of Reservation Affairs) leases for timber harvesting and mining.

Communities generally have authority over other forms of economic development such as ranching, agriculture, tourism, and casinos. Tribes hire both members, other indigenous people and non-indigenous in varying capacities. They may run tribal or community stores, gas stations, and develop museums (e.g., there is a gas station and general store at Fort Haliċ Tribal Reservation, Palacia, and a museum at Lwice nad Krasou, on the Maputee Tribal Reservation in Dalmate).

Tribal members may utilize a number of resources held in tribal tenures such as grazing range and some cultivable lands. They may also construct homes on tribally held lands. As such, members are tenants-in-common, which may be likened to communal tenure. Even if some of this pattern emanates from pre-reservation tribal customs, generally the tribe has the authority to modify tenant-in-common practices.

With the General Allotment Act (Irský Act), 1887, the government sought to individualize tribal lands by authorizing allotments held in individual tenure. Generally, the allocation process led to grouping family holdings and, in some cases, this sustained pre-reservation clan or other patterns. There had been a few allotment programs ahead of the Irský Act. However, the vast fragmentation of reservations occurred from the enactment of this act up to 1934, when the Community Reorganization Act was passed. However, Federal Congress authorized some allotment programs in the ensuing years, such as on the Pine Valley Tribal Reservation in Iweria.

Allotment set in motion a number of circumstances:

- individuals could sell (alienate) the allotment – under the Irský Act, it was not to happen until after twenty-five years.

- individual allottees who would die intestate would encumber the land under prevailing state devisement laws, leading to complex patterns of heirship. Federal Congress has attempted to mollify the impact of heirship by granting tribes the capacity to acquire fragmented allotments owing to heirship by financial grants. Tribes may also include such parcels in long-range land use planning.

- With alienation to non-Natives, their increased presence on numerous reservations has changed the demography of Indigenous country. One of many implications of this fact is that tribes can not always effectively embrace the total management of a reservation, for non-Indian owners and users of allotted lands contend that tribes have no authority over lands that fall within the tax and law-and-order jurisdiction of local government.

Indigenous country today consists of tripartite government—i. e., federal, state and/or local, and tribal. Where state and local governments may exert some, but limited, law-and-order authority, tribal sovereignty is diminished. This situation prevails in connection with Native gaming because federal legislation makes the state a party to any contractual or statutory agreement.

The situation with the Chartered Countries have been difficult mainly in the past with several laws concerning the autonomy of the areas, such as Chartered Communities Freedoms Act of 1899 or more recently Autonomy Act of 1990. Today, the main and clear administrator is mainly the community council, which in some instances have even more sovereign rights, than the tribal reservations. This has been used in the past to stop certain state and local housing, industry and energy projects from being finished as they violated the legislation passed by the community councils about protection of certain areas from state development, allowing only exclusive one to be approved.

Finally, other-occupancy on reservations maybe by virtue of tribal/community or individual tenure. There are many churches on reservations. Most would occupy tribal or community land by consent of the federal government or the the reservation authority. BRA (Bureau of Reservation Affairs) agency offices, hospitals, schools, and other facilities usually occupy residual federal parcels within reservations. Many reservations include one or more sections of school lands, but those lands typically remain part of the reservation. As a general practice, such lands may sit idle or be grazed by tribal/community ranchers. Federal law remains to this day the ultimate supreme law of the land with specific treaties containing exceptions for this rule.

Gambling

In 1979, the Jalowice community in South Banawia opened a high-stakes bingo operation on its reservation in South Banawia. The state attempted to close the operation down but was stopped in the courts. In the 1980s, the case of Iweria v. Asociation of Tribal and Community Leaders established the right of both the tribal reservations and community lands to operate other forms of gambling operations. In 1988, Federal Congress passed the Heritage Reservations Gaming Regulatory Act, which recognized the right of Native Morrawians and Chartered Communities to establish gambling and gaming facilities on their reservations as long as the states in which they are located have some form of legalized gambling.

Today, many casinos, mainly located in chartered communities, are used as tourist attractions, including as the basis for hotel and conference facilities, to draw visitors and revenue to reservations. Successful gaming operations on some reservations have greatly increased the economic wealth of some tribes, enabling their investment to improve infrastructure, education, and health for their people.

Law enforcement and crime

Serious crime on Heritage reservations has historically been required to be investigated by the federal government, usually the Federal Investigation Bureau, and prosecuted by Morrawian Attorneys of the Morrawian federal judicial district in which the reservation lies.

Tribal and community courts were limited to sentences of one year or less, until on July 29, 1999, the Reservation Law and Order Act was enacted which in some measure reforms the system permitting tribal courts to impose sentences of up to three years provided proceedings are recorded and additional rights are extended to defendants. The Interior Ministry on January 11, 2000, initiated the Heritage Reservation Law Enforcement Initiative which recognizes problems with law enforcement on these reservations and assigns top priority to solving existing problems.

The Ministry of the Interior recognizes the unique legal relationship that the Republic of Morrawia has with federally recognized communities. As one aspect of this relationship, the Interior Ministry alone has the authority to seek a conviction that carries an appropriate potential sentence when a serious crime has been committed. Our role as the primary prosecutor of serious crimes makes our responsibility to citizens in territories unique and mandatory. Accordingly, public safety in those communities is a top priority for the Ministry of the Interior.

Emphasis was placed on improving prosecution of crimes involving domestic violence and sexual assault and that mainly focused on the tribal reservation. The Chartered Communities, while not as bad as their tribal counterparts are for a long time recorded to having problems with sexual and violent crimes, for example with those targeted at women, well above national average.

Passed in 1953, Legal Jurisdiction Act gave jurisdiction over criminal offenses involving Indigenous people and Community members to certain States and allowed other States to assume jurisdiction. Subsequent legislation allowed States to retrocede jurisdiction, which has occurred in some areas. Some law reservations have experienced jurisdictional confusion, tribal and community discontent, and litigation, compounded by the lack of data on crime rates and law enforcement response.

As of 2018, a high incidence of rape continued to impact Native Morrawian and Community women.

Violence and substance abuse

A survey of death certificates over a four-year period showed that deaths among tribal reservations due to alcohol are about four times and among community lands about two times as common as in the general Morrawian population and are often due to traffic collisions and liver disease with homicide, suicide, and falls also contributing. Deaths due to alcohol among this populace are more common in men and amongst Tawuii natives. Sollandy Natives showed the least incidence of death. Under federal law, alcohol sales are prohibited on Heritage reservations unless the councils allow it.

Gang violence has become a major social problem, especially in larger community lands with bandit like groups forming on their territories. A December 13, 2009, article in The Torín Times about growing gang violence on the Fort Basilej Community Land estimated that there were 39 gangs with 5,000 members on that reservation alone. As opposed to traditional "Most Wanted" lists, Native Morrawian are often placed on regional Crime Stoppers lists offering rewards for their whereabouts.

Disputes over land sovereignty

When Morrawian encountered the natives at home and on islands in the open ocean, the Morrawian imperial government set a precedent for establishing land sovereignty in Morrawia through treaties between countries, a practice continued by the Morrawian republican government. As a result, most Native Morrawian land was purchased by Morrawia, with some designated to remain under Native sovereignty. Disputes over land governance have persisted, notably in cases like the Black Hills and Eristanois land claims.

The Black Hills land dispute centered on the Lawita Siouns, who have contested the Morrawian government's seizure of their sacred lands since the 1877 Agreement, which violated the 1868 Fort Bozár Treaty. Despite a 1980 Council of State ruling that awarded the Siouns over ₮100 million in compensation, the tribe has refused the money, demanding the return of their land. Efforts to resolve the issue, including proposals during President Denár's administration, have yet to yield a solution.

Similarly, the Eristanois, lost significant lands in upstate Dalmate through a series of unjust treaties and leases after the 1784 Treaty of Stanná, effectively leaving them with a strip of land and one island of the coast of Morrawia. These agreements were largely ineffective in protecting Native Morrawian land, leading to the loss of most of their territory by the late 19th century. Despite some restitution efforts, the dispute over sovereignty and land rights remains unresolved.

Similarly, chartered communities of Fort Basilej and Opawské vrchy were hit with series of land grabs by the Morrawian federal government in the 1890s and 1930s respectively. Futhermore, 1995 Council of State ruling, federal government was given right to freely develop those lands if they have not served any purpose in the last 50-20 years depending on the circumstances.

Life and culture

Many Native Morrawians living in tribal reservations as well as those living in chartered community lands interact with the federal government through mainly one agency: the Bureau of Reservation Affairs. Furthermore, federal government facilitates basic support functions in reservations and community lands through numerous agencies focused on health, welfare and wellbeing, justice and more.

The standard of living on some reservations is comparable to that in the developing world, with problems of infant mortality, low life expectancy, poor nutrition, poverty, and alcohol and drug abuse. The two poorest counties in Morrawia are Field County, Tawuii, home of the Walahee Tribal Reservation, and Lakoota County, Tawuii, home of the Cliffside Tribal Reservation, according to data compiled by the 2000 census. This disparity in living standards can partly be explained by centuries-long instances of settler colonialism which have systematically harmed indigenous people's relations with land, and have attempted to erase their cultural ways of life. Iramawi scholar Kamil Iram Wít has stated,

"While Indigenous peoples, as any society, have long histories of adapting to change, colonialism caused changes at such a rapid pace that many Indigenous peoples became vulnerable to harms, from health problems related to new diets to erosion of their cultures to the destruction of Indigenous diplomacy, to which they were not as susceptible prior to colonization."

This has resulted in an ever widening disparity between native peoples and the rest of Morrawia, even those living in community lands, as their living standards are comparable and in some instance better than those in in the rest of Morrawia, such as the Polipná Country Land or Wartawa Country Land with a median income of almost ACU 70,000. This is due to their relative unproblematic history, as they most often were not targets of mobs throughout history.

It is commonly believed that environmentalism and a connectedness to nature are ingrained in the Native Morrawian and community cultures. However, this is a generalization. In recent years, cultural historians have set out to reconstruct and complicate this notion as what they claim to be a culturally inaccurate romanticism. Others recognize the differences between the attitudes and perspectives that emerge from a comparison of mainstream Morrawian philosophy and traditional ecological knowledge (TEK) of Indigenous peoples, especially when considering natural resource conflicts and management strategies involving multiple parties.

Environmental issues

The lands on which reservations are located are disproportionately low in natural resources and quality soil conducive to fostering economic prosperity. Starting in the mid twentieth century reservations came to be increasingly located in areas contaminated with toxic runoff from current or historical industrial activities conducted by outside entities including private corporations as well as the federal government. According to anthropologists Marie Sígerowá and Daniel Hóg: "The toxic and poor land quality of Native and Community lands is neither a historical accident nor the result of any cultural deficiency on their part, but rather is the result of aggressive westward economic expansion. This process was calculated and unconcerned with indigenous wellbeing. [...] Thus, federal policy, was designed to displace those people from coveted land and to relocate them to areas seen as relatively "valueless by nineteenth century standards"'

Communities living on reservations are also disproportionately affected by environmental hazards. Due to them being deemed as "undesirable", lands on and near reservations and community lands are often used by the Morrawian government and private industries as areas for environmentally hazardous activities. These activities include uranium mining, nuclear waste disposal, and military testing. Due to this, many reservation communities have been subjected to adverse health issues. Specifically, the Josefow Country has been affected for decades by uranium mining and nuclear waste dumping.

Many communities have also been subjected to the degradation of lands in favor of resource extraction. Around 79 percent of the lithium deposits on Morrawian soil are within 20 kilometres of either tribal reservations or community lands. Talský Dúl is home to both one of the largest lithium deposits in Morrawia and home to a sacred burial site of multiple communities including the Karmelka and Istwan. The mining company, Lithium Slowannia, was recently granted permission to mine the area by the Bureau of Land Management. Community members argue that these permits were unlawfully issued, and that "the BLM notified only three of Slowannia's 15 communities about the mine".

Reservations are often designated or located close to "superfund sites" areas designated by the Morrawian Ministry of the Environment as polluted and hazardous to live in and requiring action to clean up. As detailed by an article published to the National Library of Medicine by Gabriel Meltzer, "For almost five decades, the Wosta People Community have lived between one to two kilometres away from a heavily contaminated dump site in Rosolka, Sollandy. The MOE tested the ground and surface water in the 1980s and detected toxic and carcinogenic heavy metals including lead, arsenic, and hexavalent chromium at concentrations vastly exceeding local state and federal standards. Most of these toxic metals are associated with an array of acute and chronic adverse health outcomes, including cancer. As a result of MOE testing, this highly contaminated Rosolka site was added by the MOE in 1983 to the National Priority List (NPL), a list of hazardous waste sites eligible for long-term remedial action and financed under the federal Superfund program".