Massanism

| Massanism | |

|---|---|

| ⵅⴰⴱⴰⵔ ⵣⵉ ⵎⴰⵙⵙ Xabar zi Mass | |

An interlaced 10-pointed star is the most common symbol of Massanism | |

| Classification | Heliolatry |

| Scripture | Atem zi Mass |

| Region | Talahara, Tyreseia, Charnea |

| Language | Takelat |

| Founder | Daya (legendary) |

| Origin | circa. 2,500 BCE Talahara |

| Members | 28.5 million |

Massanism (Takelat: ⵅⴰⴱⴰⵔ ⵣⵉ ⵎⴰⵙⵙ; Xabar zi Mass), literally Counsel of the Saint, is the traditional religion of the Kel Aman and Kel Hadar peoples of Talahara. Massanism is distinct from other Kel faiths but shares key features with of heliolatry and ancestor veneration. Major differences include cosmology and religious practices between the two faiths.

The religion has been practiced in some form by the Kel Aman and Kel Hadar on the Rubric Coast since at least the 3rd millennium BCE. Worship was repressed under the Latin occupation but resurged after independence. Interaction between both Coptic Nazarist and 'Ifae Azdarin sects has resulted in syncretic philosophies, though these beliefs are not widespread.

Worship in Massanism centres on prayer and reverence of the sun and ancestor spirits. Chief among these ancestor spirits is Daya, the legendary ancestor of the Kel and the daughter of the sun. A particularly faithful, dutiful, or righteous ancestor may be venerated as a saint, or mass (plural: imassan), though all adherents of the faith are considered to become spirits and carry influence on the physical world after their deaths. Religious leaders are most often the eldest members of traditional clans and tribes. Younger members may rise to leadership positions if they are judged to have followed an accelerated path toward sainthood. An oppositional entity known as Sulwar is present in textual and traditional dogma and is relevant to both the cosmogony and eschatology of the faith, but has little bearing on daily worship and experience for the Massanist faithful in the present-day.

Beliefs

The teachings of Massanism are recorded in the "Atem zi Mass", or "Way of the Saint". The Atem zi Mass is the collection of various oral histories and older written records, dating as far back as the 3rd millennium BCE. The Massanist faithful believe that Maɣeq, the Sun, is the mother of all life and carries away the spirits of the dead into the wind. According to tradition, Daya was born into the world to bring unity and peace. Daya was born with a splinter of the Sun's soul in her body and passed the splinter on to her descendants - the Kel.

Following the path of great figures from the past leads a practitioner on a path to sainthood. A few select individuals who have emulated saints of the past and led righteous lives may be declared and accepted as saints within their lifetimes. The majority of saints are recognized after their deaths. Working towards sainthood is considered to elevate the spiritual health of an entire clan or kinship group.

Massanism is not inherently evangelist. While centered on the Kel, however, converts can be accepted after a blood ritual is performed. The ritual is said to share a splinter of a splinter of Maɣeq the Sun Mother with the convert and thereby adopt them.

Cosmogony

According to the Atem zi Mass, Maɣeq the Sun Mother lived together with Ašukanak the Ocean Father and Orahan the Earth Aunt/Uncle. One day, Sulwar arrived and murdered Ašukanak and Orahan. Maɣeq escaped from Sulwar and carried the souls of Ašukanak and Orahan away. After a long time, the two souls begged Maɣeq to return to their bodies to create the world and sacrifice their souls to create life that could protect Maɣeq and ward off Sulwar.

Maɣeq created a world from the body of Orahan and the blood of Ašukanak. She created all life both plant and animal. The first among all creatures were the humans. However, the first humans were territorial and warlike. They fought and killed one another and even their clans collapsed into infighting and kinslaying. Seeing that her creations would inevitably destroy themselves, she tore a splinter of her own soul away and created Daya, her only child and daughter.

Daya united a great tribe and shed her blood into them, birthing the Kel Aman and Kel Hadar. After creating her people and leading them to survive the turbulent world, Daya passed on to the spirit world where she resides as the greatest saint. Those of her bloodline who pass on from the physical world join her as spirits riding on the wind. Those who are not imbued with a splinter of Maɣeq's soul are doomed to be enslaved and eaten by Sulwar.

Eschatology

According to later tablets from the 1st century CE, the end of the world will come about when the winds are so saturated with spirits that the planet is consumed by a massive vortex. All who remain will be carried away by the wind, led by Daya, to become spirits themselves or fall to Sulwar. All the spirits will battle Sulwar and its slaves. After one thousand years of war, Sulwar will be vanquished and its slaves will be freed. The spirit world will be united with the physical world and every generation will live in peaceful harmony with every preceding generation for eternity.

Roles of the Sun

As its creator and guardian, Maɣeq takes an active role in the world. New life is sent down through the winds into the world and old souls are taken away into the wind. Maɣeq is prayed to regularly and asked for blessings and guidance. The sun is considered to be responsible for good or bad crops, long life, artistry and creativity, motivation and industry, and good or bad fortune. As the single most powerful force of goodness and creation, Maɣeq is a supreme being worthy of veneration to Massanists.

Roles of ancestor spirits

The souls of the Kel who have passed away join the winds of the spirit world. The more closely an individual pursued the path to sainthood in life, the more likely they are to be venerated as a mass, or saint, in death. A few notable historical figures have been recognized by the title in life, but most only after death. A select few heroic figures in history are known as imassaškarin, or venerable saints. These figures are considered to be the elders of clans of spirits, guiding them along through the winds.

Many of the assumed roles of ancestor spirits are related to their distinct character. Prayers to the spirits are often done to ask for guidance or advice in following their footsteps. Other requests relate to the winds through which the spirits flow. Massanists may request that spirits bring good weather or drive away the bad with the wind. Others may associate winds with fortune or pestilence and tailor their prayers accordingly. Winds in general are considered to protect the faithful. The transit of the sun through the sky is understood as Maɣeq looking over the world, including the far side, but when she cannot lend her gaze to her people the spirits keep watch. Still nights are considered to be particularly dangerous and bring ill omens. Especially superstitious adherents may refuse to leave their homes on a windless night.

Practices

As Massanism lacks a central authority, religious practices vary from region to region. General features are preserved and interconnected with broader Talaharan traditions. For example, in following with the tradition that Orahan sacrificed their body for the world, aunts and uncles tend to take active roles in raising children. This role typically extends beyond immediate family and in some clans children are raised together by an entire kinship group. Another common but not entirely universal practice is scarification, usually in patterns related to Maɣeq, Daya, particularly venerated spirits, personal accomplishments, or general clan markings. The main aspects which are held in common by all Massanists are the acts of prayer, pilgrimages, and funerary rites.

Clergy

Massanist prayer and religious ceremonies are communal affairs led by a loose organization of clerics. Historically, Massanist priests were subject to the customary authority of a high priest appointed by the monarch and later by the Court of the Lions. Despite this, secular authority superseded the political power of the priest class throughout most of Talahara's history. There are two main classes of Massanist clergy: the priesthood and the shrine guardians.

Massanist priests are community-based faith leaders. Priests lead their congregations in prayer, officiate religious ceremonies, offer spiritual counsel to their communities, and maintain the temples and local shrines. The priesthood is non-gendered, though the priesthood in Talaharan communities would often match the gender of important regional saints. Before the 1838 revolution, priests would appoint their successors, often choosing family or clan members, though custom demands that a candidate completes ten sacred pilgrimages prior to being invested as a member of the priesthood. After 1841, the priesthood reformed to an elected position, though terms vary by commune. As the customary qualification of having completed ten pilgrimages is still broadly applied, successors are de facto assigned by being directed and provided the opportunity by the religious community to embark on the requisite pilgrimages.

The shrine guardians are a decentralized and historically semi-martial society that maintains and defends shrines in communities and remote waystations along pilgrimage routes, ensuring safe passage for pilgrims and merchants both from banditry and the harsh elements in remote areas of Talahara. Many societies of shrine guardians subsisted on donations from their local communities, pilgrims, and traveling merchants. Others benefited from the patronage of political figures and the clans whose ancestors' spirits were venerated in a particular shrine. In the present day, the duties of the shrine guardians have been deprofessionalized with a greater reliance on local communities for the maintenance of shrines.

Prayer

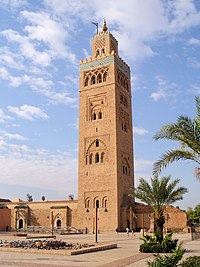

Temples (izalalan) are structures dedicated to Maɣeq. Shrines (igdalan) are places for ancestor worship and typically contain reliquaries of a spirit's earthly belongings. Generally, temples contain several shrines. Prayer is typically done in groups at shrines and temples or alone for individuals on a pilgrimage. Prayers to Maɣeq are only done under the shining light of the sun while prayers to ancestor spirits require a blowing wind to be heard. As such, shrines and temples are typically open-air structures with little in terms of walls or permanent fixtures. The optimal setting for a shrine or temple would be at a high elevation or in a wind-swept canyon. In small communities or where it is generally impractical, prayers are conducted outside of temples and shrines. If a community has a temple but the air is still or there are clouds directly over the site, the congregation may simply move to where there is a gap in the clouds or where a breeze might be found. In dense urban areas, temples are often built atop tall towers.

Pilgrimage

Pilgrimages are long journeys undertaken to follow the path of an ancestor at a key moment of their life. They may be undertaken for a variety of reasons, typically either to seek specific guidance or inspiration along the path or simply to experience the holiness of the journey. There are several famous pilgrimage routes. The Artists' Pilgrimage from Takalt to Mestaɣanim was originally undertaken thousands of years ago and is believed to provide inspiration for artists. Daya's Path is long journey beginning at Tallidat Tigmit near the border with Charnea and ending in Maktarim.

Pilgrimages are usually undertaken in groups though they are unique in their own traditions. Pilgrims undertake their journeys for personal reasons and as such pray for guidance alone. Most pilgrimage paths link between different temple and shrine complexes and pilgrims stop to pray at each so long as the conditions are favourable for their prayers to be heard.

Funerary rites

Funerary rites are another uniform element of Massanism. Bodies of those who are deceased are to have their flesh cremated, the bones ground into ashes, and the ashes scattered to the winds. Doing so releases their spirits into the spirit world. Bodies that are left to decay may result in the soul being lost to Sulwar. Once cremated, ashes can wait to be scattered until convenient, though an ancestor may not be properly venerated until their soul has been released.

Demographics

The number of Massanists globally is approximately 28.5 million, the vast majority of which are Kel Aman or Kel Hadar and reside in Talahara. Approximately 43% of Talaharans (roughly 22.5 million) identify religiously as Massanist following a major secularization movement in the late 19th century. Despite this, a larger percentage of the population is estimated to take part in public religious ceremonies and identify as "cultural Massanists". The remaining six million adherents are largely found in Tyreseia (approximately five million) and Charnea (less than 300,000). Small Massanist communities are present across the international Talaharan diaspora, but the importance of local shrines and the importance of proximity to ancestor spirits make it difficult to practice the faith in foreign lands.

Syncretism

Azdarin syncretism

The Ishantin N'Ašukanak (Children of Ašukanak) is a syncretic sect that flourished between the 9th and 16th centuries CE. Adherents of the faith identify Ašukanak the Ocean Father with the Azdarin deity Gedayo and claim that Ašukanak fled alongside Maɣeq when Orahan was murdered. The Chosen King, Mesfin, is identified as equivalent to Daya. It is purported that all life was made from Orahan, the Kel were imbued with splinters of the soul of Maɣeq while the Yen were later imbued with splinters of Ašukanak through the bloodline of Mesfin. Adherents of the sect believe the blending of all three souls creates the greatest spiritual power. In order to pray to Ašukanak, the Ishantin engage in the same rituals as the Yen, including ceremonial washing.

Nazarist syncretism

Aynaɣ Uridranuat (the Invincible One) was the subject of a syncretic cult that was primarily active between the 4th and 8th centuries CE. Minor sects continue these traditions to the present day, though there are likely fewer than 500 adherents in Talahara. The cult likely arose from an attempt to reconcile Maɣeq as a solar deity with Coptic Nazarism. Ancestor worship and the power of spirits were generally discarded except for the more widely-venerated saints which were accepted into local canons. Saint Daya was likewise reinterpreted as a prophet rather than the source of a holy bloodline.