Talaharan Civil War

| Talaharan Civil War | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

Anarchist woman at the Third Battle of Maktarim | ||||||||

| ||||||||

| Belligerents | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Commanders and leaders | ||||||||

|

|

|

| ||||||

| Strength | ||||||||

|

16,500 soldiers 45,000 militia 2,000 mercenaries |

1,200 soldiers 185,000 militia 6,000 mercenaries |

10,500 soldiers 280,000 militia | ||||||

| Casualties and losses | ||||||||

|

42,000 wounded 11,000 killed |

29,000 wounded 16,000 killed |

58,000 wounded 21,000 killed | ||||||

| 100,000-150,000 civilian deaths | ||||||||

The Talaharan Civil War, also known as the Talaharan Revolution and the Talaharan Anarchy was a war that erupted in 1834 between three factions in Talahara. The conflict began with the overthrow of the monarchy of the Third Talaharan Kingdom by the Republicans; a faction spearheaded by the affluent liberal merchant class. The conflict rapidly evolved to include the Anarchists; a nascent movement of commoners and slaves demanding an upheaval of the social and economic order. After four years of war, the Anarchists ultimately emerged victorious over both the Republicans and the Royalist remnants.

The Civil War left a lasting legacy on the world, with the new United Communes of Talahara forming the world's first revolutionary socialist republic. To Talahara's immediate east, popular unrest would result in syndicalist uprisings and eventually revolution within several decades. Future writers including Arthurista's Harrison Werner and Tsurushima's Kamikawa Yukichi, drew on the theory and lessons of the Civil War and its core thinkers.

Historical context

Structural conditions

In the centuries leading up to the Civil War, the merchant class of Talahara began to eclipse the ruling nobility in terms of material wealth and soft influence. On their part, the merchant class began to clamour for additional political power while the vast majority of slaves and commoners languished under exploitative conditions. Despite the attempts of the nobles and the merchants alike to repress the lower classes, improved infrastructure and the displacement of peoples from their traditional crafts and environments resulting from industrialization expanded the commoners' abilities to communicate and mobilize. Further unrest and revolts throughout the 18th century put increased pressure on the nobility which responded by criminalizing vagrancy and vagabondism at the beginning of the 19th century.

The criminalization of vagabondism led to conflict with the minority population of free Kel Hadar who had maintained nomadic pastoralist lifestyles for several millennia. The cultural and religious elite of Talahara, which included a large portion of the military, supported the preservation of the Kel Hadar’s rights to nomadism which caused internal strain in the regime. Several clashes occurred between the nomads and authorities before the law was amended to carve out an exception for the Kel Hadar. These exceptions had two major effects: Firstly, there were mass protests among the Kel Aman (nobles, merchants, and commoners alike) who begrudged unequal treatment in the context of a developing conception of universal rights. The second effect was that many otherwise repressed Kel Hadar adopted nomadic lifestyles ostensibly as covers for fomenting unrest and revolutionary sentiment. Over the ensuing decades, violent outbursts and independent repression by merchants spread as the Court of the Lions began to lose its grip over the state.

Slavery was a relatively commonplace institution in Talahara from antiquity to the early modern era. By 1830, roughly 35% of the country's inhabitants were chattel slaves. Slaves were typically drawn from Kel Tenere or Kel Hadar clanspeople captured in internal conflict or thereafter born into servitude. The majority of slaveowners were traditionalist Kel Aman noble landowners. A further 45% of the population was estimated to have worked in indentured contracts which were increasingly common arrangements between free lower-class Kel and liberal capitalists.

Liberal and revolutionary ideologies had become the dominant discursive forces in the nation among the religious, military, and common classes by 1833. Across all corners of the kingdom, the acceptance of the kings’ authority was rapidly waning. The liberal landowning class used their resources to spread their influence and agitate politically for abolishing noble privileges. While the affluent merchants would be the primary beneficiaries of a new liberal order, their dogma was popular with many commoners as well, particularly those who were sold on narratives of opportunity and class mobility. While the anarchists agreed on abolishing privilege, they also sought to definitively end slavery and recentre the labourer as the core unit of society and redistribute wealth such that the merchants could not buy their own privileges at the expense of the poor.

Ideologies

The Talaharan Civil War was a conflict between three ideological groups: the declining traditional forces of monarchism, the rising industrial liberals, and the nascent socialist movement of Talaharan social mutualism.

Talaharan monarchism

Unlike other monarchies in the world, the Talaharan monarchs of the modern era had no philosophy of divine right to rule. Rather, the investiture of autocratic power in the hands of a single monarch was seen as a reflection of natural law. The beginning of the Third Talaharan Kingdom, wherein the throne was awarded to the senior-most member of the eminent Talaharan clans, explicitly dictated the monarchy as an element of the natural order of the world and a function of life's mechanisms, but not that any given individual was divinely ordained to rule.

The Royalist faction was predominantly led by twenty ruling clans, ten Kel Aman and ten Kel Hadar, and their elder kings who sat in the Court of the Lions. Members of the Court of the Lions obtained their positions via seniority. The ruling clans each had dominion over a set of sub-clans, usually controlling a subset of tradespeoples across a nebulous geographic area. In principle, the clans ruled over peoples and not territories, so the jurisdictional boundaries between clans could be nebulous, especially in cases of intermarriage between clans. The different clans also had a great disparity in wealth. Since the foundation of the Third Kingdom, taxes were excised uniformly across the clans and budgeted by the King-President of the Court of the Lions. However, many Kel Aman clans obtained independent wealth as merchant houses, as slavers, or as planters.

As the power of independent merchants and business owners who were not members of the ruling clans grew in the early-modern period, the legitimacy of confining the natural right to rule to a number of historical clans became increasingly suspect. The material capital of the merchant class eclipsed that of the rulers by the mid-18th century. The right to rule thus became a question of political and economic expediency, efficiency, and appeals to tradition. With industrialization and a changing world, the Royalists appealed to a sense of romanticism, arguing that burgeoning industrialization had to be tempered by the natural order.

Despite protests, material conditions made the censuring or limitation of the merchant classes almost impossible without starting a war. The turn of the 19th century also saw the success of liberal republican movements across the world which fueled further discontent among liberal Talaharan merchants.

Liberalism

Liberalism is a social, political, and economic philosophy that asserts a theory of universal rights and freedoms. According to liberalism, all individuals are equal within the natural world and deserve equal rights. In a political sense, liberal ideology called for popular representation in government and the elimination of traditional socio-political hierarchies. In an economic sense, liberalism asserts the right to private property and freedom of commerce as extensions of personal rights and freedoms.

The philosophy of liberalism emerged in the 17th and 18th centuries, with some earlier precursor thinkers. Its emergence was largely correlated with industrial development and the radical socio-economic upheaval that accompanied it. Revolutions in transportation and communication technologies also facilitated the exchange of new, radical ideas and conceptions of broad, modern, democratic ideals. Social clubs such as the Ten Thousand Citizens Committee based in Ifurša became important circles for networking, sharing assets and ideas, and building furor against the restrictions imposed by the ruling kings.

The extent of liberal philosophy has been variable even within broadly liberal societies. The definition of universalism has historically been varied, with some theorists and societies only conferring rights among a limited subset of humankind - namely men, individuals with property, or people of a certain ethnicity or religion. Numerous liberal societies have justified the practice of slavery or the limitation of political rights to the unpropertied based on a limited theory of personhood or a question of an individual's stake in society. After Sante Reze abolished slavery in 1712 CE, there was increasing international and commercial pressure against slavery. In Talahara, the liberal movement grew to oppose the institution of slavery in the latter decades of the 18th century, but promoted the use of indentured labour as an ostensibly free market alternative. This endorsement put Talaharan liberals at odds with other liberal societies of the era.

Social mutualism and anarchism

Talaharan social mutualism was among the first explicitly revolutionary and self-ascriptive socialist movements in the world. Developed by a developing group of working-class intelligentsia, social mutualism understands itself as the next step in socio-economic development from the conception of universal rights developed by liberal ideology. In addition to the liberal revolution in Ludvosiya and the theories of the Talaharan liberal class, early Talaharan socialists such as Mass Ziri Akli were inspired by communalist societies in northeastern Norumbia.

In terms of its objectives, social mutualism seeks to abolish all unjust hierarchies, both political and economic. The core tenet of social mutualism is that resources essential to life ought to be distributed evenly across society, with no private property or primitive accumulation of resources to the deprivation of others. Economic exchange ought to be based on need and resource use based on usufructuary rights. Unlike orthosocialist theories, social mutualism calls for a decentralized economic organization along a free albeit socialist market, rather than a centrally-planned command economy. Social mutualism also called for extreme emancipation and social revolution, guaranteeing freedoms for different expressions of gender, sexuality, and racial identity.

Social mutualists opposed both the liberals and the monarchy on the grounds that both political systems relied upon unjust hierarchies to impose order on society. In the case of the monarchy, this hierarchy was based on a so-called natural order which placed certain individuals above others. In the case of the liberals, economic hierarchies dominated the lives of individuals in the capitalist system and despite egalitarian philosophy, poverty remained inescapable due to the structural economic hierarchies imposed on the lower classes.

Agitators against both the monarchy and the liberal class were often labeled as anarchists who opposed any system of governance or imposing order altogether. Social mutualist movements began to adopt this label, including those who sought a more harmonic reorganization of society along non-hierarchical lines rather than strict abolition of all government structures.

Conflict

The Talaharan Civil War began as an intense conflict between Republican and Royalist factions which devolved into a country-wide civil war that claimed the lives of at least 150,000. The conflict involved various forms of warfare, from conventional line battles, skirmish tactics and guerilla warfare, and ideological conflict. The conflict began with a series of uprisings led by conventional forces and the realm was ultimately thrown into chaos following the attempted mass assassination of the Royalist leadership. Thereafter, anarchist forces gathered momentum and overcame the other two factions to emerge as the victor of the war.

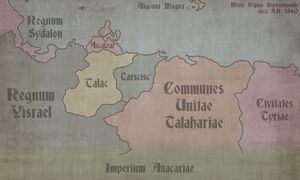

The conflict also featured foreign interventions, including the Yisraeli occupation of the northern regions of Kirthan and the formation of the Protectorate of Taršiš. Rezese mercenaries were enlisted by the Republicans in the early stages of the war, but several Rezese houses also offered indirect support to the anarchists, motivated by opposition to the chattel slavery and the indentured labour endorsed by the Royalists and Republicans, respectively.

Preamble

In October of 1833, prominent liberal ideologues and business owners met over three weeks at the Ten Thousand Citizens Committee in Ifurša, devising a plan to overthrow King-President Medur IV and the Court of the Lions and to establish a liberal republic. The Committee created a draft of a new liberal constitution and laid plans for a coup. By the end of the three weeks in Ifurša, an agricultural magnate named Zemrassa Waguten was acclaimed as the shadow president of the new republic, and the first concrete steps of the coup plot were put into motion.

Among the Republican conspirators was Warmaksan Kabil, a retired colonel from the Royal Talaharan Army who had entered into business manufacturing arms in Mutafayil. Kabil was nominated as shadow minister of defense and placed in charge of assembling a military force to execute the coup and contend with the Royal Talaharan Army until the legitimacy of the republic could be assured. To that end, Kabil made contact with several Rezese mercenary companies from the Nine Cousins and procured their services with the collective resources of the liberals. In fact, Kabil assembled a much greater force than he'd been authorized to with credit, concerned that the coup would not proceed as smoothly as planned.

In February of 1834, the Warchief of the Court of the Lions, Karim N'Tsabunar, was advised of large mercenary movements into the country and privately alerted King-President Medur IV and the rest of the court. Several mercenaries were bribed to change their allegiances and divulged information regarding their previous employment contracts. The court was unmoved by the limited information provided, accepting that the mercenaries were being hired for commercial ventures to southern Scipia, unaware of the true numbers or intentions of the forces.

Phase one

Outbreak

On March 29, 1834, the Court of the Lions was in session when a large group of assassins struck, killing sixteen of the twenty members in addition to several dozen guards and retainers. The coup plotters nevertheless took control of the central palace and proclaimed the Republic of Talahara. Parallel uprisings in Ifurša, Mutafayil, and Rušadar granted the Republicans a firm hold in the country's northwest, but Maktarim itself remained disputed territory, with a major contingent of the Royal Army successfully deployed to combat the Republican mercenaries.

The Republicans' plans were further embattled on March 31, when it was revealed that King-President Medur IV and Warchief Karim N'Tsabunar had escaped the assassination attempt in the Court of the Lions and fled east to gather border garrison forces and to issue a general levy in the agricultural heartlands around Takalt and along the Talaharan shore of the Qeshet River. With a sizeable militia raised to support the professional soldiers of the Royal Army, the Royalist forces had secured an east-west front along the Rubric Coast and avoided ceding momentum completely to the Republicans.

As the country was plunged into civil war, anarchists began to coordinate and mount their own resistances to both the liberal Republicans and the traditionalist Royalists in farming towns, factories, and ports. The loose ideological network began to coordinate to build a wider movement and civic, philosophical, and military leaders began to converge in the port city of Rušadar. Ideologues and philosophers who had been travelling abroad were recalled to the country, including Ziri Akli who immediately booked passage on a ship from Norumbia when news arrived of the war.

Republican campaign

The Republic of Talahara's provisional government assembled a war department and appointed Warmaksan Kabil as the commander-in-chief or Warchief of the Republican Army, with the largely Rezese mercenary forces bolstered by volunteer militias. A conscription order was issued in Maktarim, but approximately 70% to 80% of the eligible population failed to report for service. The assembled military force was initially scattered across the hotspots of revolution and Warchief Kabil chose to focus on uniting the forces to focus on a direct assault against the Royal Army in the east. As the Republican forces withdrew to relieve the capital's defenders, the remaining civilian administrators struggled to maintain a grip on the unruly population.

The reformed Republican Army routed the Royal Army forces on May 7, 1834, in the First Battle of Maktarim which was the first major field battle of the civil war. In the capital city, insurrectionist activity continued to stimy the efforts of the administrators, but the Republican war department chose to continue pushing eastward, determining that the organized Royal Army was a greater threat than the Anarchists. Warchief Kabil dispatched a detachment of mercenaries south to besiege the fortress of Avana and then pressed on westward to the city of Mestaɣanim and then southeast to Weskera. At Weskera, the Republican Army was stalled by a series of defensive earthworks and entrenched soldiers from the Royal Army. Faced with the prospect of the Royal Army receiving reinforcements from the east, the Republican Army engaged the defenders and were ultimately repulsed in the First Battle of Weskera between July 1-5, 1834. As a result, the Republican Army withdrew to Mestaɣanim to entrench and support the siege of Avana.

While probing skirmishes continued through the summer of 1834, the intense heat made each belligerent hesitant to wear down their fighters. The Royalist garrison of Avana ultimately surrendered on September 14, 1834, though many of the captive Royal Army soldiers broke their bonds and escaped to Royalist lines in October. With the inevitability of a clash between the two main armies, each faction reinforced its respective position and the war became a stalemate through to the winter of 1835. During the winter, the Republic employed the captured ships of the Royal Navy to found its own Republican Navy under the command of Admiral Ili Kinawa. The Republican Navy proceeded to blockade the Royalist port of Munaxdri.

Intervention and unrest

Protectorate of Taršiš

With the Royalist forces confined to the east and the Republican Army encircling them, the Anarchists seized control of Rušadar and the town of Lakišt and city of Kirthan to the south between February and April of 1835. These uprisings were disregarded by the Republican Army's general staff who continued to regard the Royalist forces as their primary enemy. Once the uprisings spread as far the town of Batana in the Ninva desert, close to the Timna region, the Kingdom of Yisrael launched an intervention into Talahara, with Yisraeli soldiers entering the city of Kirthan on June 25, 1835.

In Yisrael-proper, similar uprisings across urban centres were suppressed by the government, but apprehensions among Talahara's neighbours rose significantly. From 1835 through to 1838, hundreds of Yisraeli anarchists and socialists travelled to Talahara and joined local communes.

The stalemate between the Republican and Royal Armies in the east proved to be a trap for the forces and the Republican government was unable to pull forces back to address the foreign invasion. The Republicans ultimately made a diplomatic appeal which was only hesitantly accepted by the Yisraeli court which regarded the Republican government with a great deal of suspicion. The Yisraeli court in turn expressed that the purpose of the intervention was to restore order in the region as unchecked revolution presented a broader threat to West Scipia. When Yisraeli forces moved north as far as Rušadar in August 1835, the Republican government conceded Yisraeli suzerainty over the west for the duration of the war, with the proclamation of the Yisraeli-guaranteed Protectorate of Taršiš on August 26, 1835 in exchange for a promise to not further intervene on behalf of the Royalists.

Anarchist uprisings

The Yisraeli occupation of the west and the establishment of the Protectorate of Taršiš pushed the Anarchist organizers further east. From the autumn of 1835 into the winter of 1836, Anarchist cells formalized a network of connections, uniting insurrectionist fighters with an ideological and intellectual core. Anarchist cells and uprisings continued as the standoff between Republicans and Royalists created a void of authority in much of the country. In the cities of Mutafayil and Ifurša, the Republican magistrates were removed by mobs of free citizens and slaves who established the first large-scale communes of the country. These mobs adopted the label of "Black Guards" and functioned as armed cells of resistance. Much of the revolutionary activity and the nature of the rejection of the Republican government remained surreptitious. Following the concession of Taršiš, the Republican government was also active in downplaying the extent of revolutionary activities within their borders.

During the fall of 1835, the Royal Army launched two counter-offensives against the Republican Army, incensed at the concession of several major cities to a foreign power. The Third Battle of Weskera ultimately pushed the battlelines past the Republican entrenchments, but were stalled short of Mestaɣanim and the capital and were ultimately turned back to Weskera between November 14-17, 1835. As the tide was turning against the Royal Army, the Republicans diverted roughly half its fleet from Munaxdri and blockaded Mutafayil and Ifurša to limit the resources and combat the Anarchists. In January of 1836, the Republican Navy bombarded the city of Ifurša and landed two battalions of naval infantry to retake the city. While the Republican forces were able to capture and occupy the city's harbour district, they were unable to breach beyond the harbour's fortified walls to the city-proper and the Anarchist commune remained entrenched.

By the spring of 1836, Anarchist influence in Maktarim was growing and the purported chief demagogue of the Anarchists, Ziri Akli, was alleged to have relocated to the capital to coordinate revolutionary activities in the dense urban sprawl. In June, a Tyreseian soldier named Valeju Papin led a Tyrian expeditionary force across the Qeshet to protect Tyrian interests. "Papin's Adventurers", as they came to be known, arrived in Talahara in June 1836 and defected to the Anarchist cause by July. The Adventurers ultimate made it to Maktarim and threw in with the Anarchist organizers in the capital.

Phase two

Royalist advance

Through the winter of 1835-1836 the Royal Army remained deadlocked with the Republicans at Weskera, with two subsequent battles, each of which were indecisive. In an effort to maintain supplies, the Royalists engaged in a number of chevauchée actions in between Avana and Wasif. In June 1836, a clash between 2,000 Republican cavalry and 3,000-strong Royalist cavalry regiment led by General Tegwesta N'Tayoro outside Wasif constituted the single largest cavalry battle of the war, resulting in a tactical victory by the Royalists and the sacking of Wasif. While supplies were routed back north to the Royal Army in Weskera, the sacking saw a significant decline in popular support of the monarchy.

The summer of 1835 had seen an abatement of fighting after the casualties caused by the intense heat of 1834. However, the Warchief N'Tsabunar elected to surprise the Republicans by launching an offensive in the hottest month of the year, straddling July and August in the traditional Talaharan calendar. The 1836 summer offensive caused significant attrition for both Royalists and Republicans and following a victory at the Fourth Battle of Weskera in September, the Republican forces were forced to withdraw to the outskirts of Maktarim which remained contested by Anarchist forces in the city centre. Seeking to capitalize on the conceded ground, N'Tsabunar force marched the Royalist forces to the capital. With daily temperatures in excess of 30°C even by October, the rapid pace of the advance on Maktarim exacerbated the attrition. While the Royal Army numbered some 50,000 soldiers and irregulars after Weskera, only 17,000 arrived in Maktarim in fighting condition on October 4, 1836.

While N'Tsabunar attempted to avoid a direct engagement until the Royal Army could be bolstered, the Republican Army under the command of Warchief Kabil forced an engagement on October 15 where the 80,000-strong Republicans routed the Royalists. With the Royal Army in disarray, the Republicans were able to pursue in comparative order, especially with the falling temperatures of the autumn. In December 1836 the remnants of the Royal Army were encircled at Takalt. N'Tsabunar, who had served with Warmaksan Kabil prior to his retirement, personally surrendered to the Warchief of the Republic on December 11 and was transferred to a prison in Avana, leaving King-President Medur IV to assume control of the Royalist remnants in Munaxdri and Gawawa.

Organization of the Anarchists

As the Republican Army withdrew from Maktarim in pursuit of the Royalists, the ranks of the Anarchists who controlled the city centre began to swell with the ranks of defecting Royal Army soldiers. Joining the numerous Black Guard organizations in the city, the defectors were reorganized into a revolutionary organization called the Central Commune Army. The Central Commune Army was led by a committee of Maktarim-based revolutionaries, but Baligan Amasen, a former colonel in the Royal Army with Anarchist sympathies, emerged as a distinguished field commander. Anarchist influence over the city expanded and the rearguard of the Republican Army was removed from the city in early 1837. The Black Guards branched out to extend contiguous influence across the Ifurša-Maktarim-Mestaɣanim region.

On January 23, 1837, the the Republican Army divided in half, with one portion pursuing the Royalist remnants in the east under the command of Warchief Kabil while the other half under the command of Guyemar Achinet turned back west to deal with the Anarchists. It was initially unclear to the Republicans if the Central Commune Army was aligned with the Anarchists or the Royal Army and the organization and size of the resistance caught Achinet's army off-guard. Despite requesting reinforcements from the Republican garrisons in Avana, Haluwaxam, and as far as Mutafayil, Achinet's force was defeated before help could arrive in the Third Battle of Maktarim in early March 1837. Word of the defeat was not transmitted in time for the first two waves of reinforcements to reorganize and the successive defeats of major contingents of the Republican forces marked a major turn in the course of the war. With the western garrisons of the Republic defeated, Black Guards seized control of the western cities of Talahara, standing off with wary Yisraeli forces across the new border with the Protectorate of Taršiš.

Phase three

Defeat of the Royalist remnants

With the prospect of becoming encircled by the Royalist remnants and the rapidly growing Anarchist forces, Warchief Kabil directed the Republican Army to proceed eastward to close off that front. On March 29, 1837, Munaxdri was besieged. Though the King-President was able to escape the encirclement, with the avenues to the sea cut off by the Republican Navy and the uncertainty of the situation east in the Tyrian states, he elected to move south to the sole remaining stronghold in Gawawa. Munaxdri remained encircled by Republican forces while Kabil turned south in pursuit of the King-President. As both Munaxdri and Gawawa were under siege, the Republicans were counting on the attrition of the summer to break the last Royalist resistance. However, the Republican Army's supply lines were subjected to frequent harassment by Anarchist forces which continued to consolidate the west in a loose confederation of militant groups, ostensibly under the direction of a community of philosophers and demagogues based in Maktarim.

The fortress of Gawawa was overcome on August 14, 1837, and King-Present Medur IV was captured by the Republican Army. President Zemrassa Waguten of the Republican government requested to have the King-President delivered to Avana for trial. However, with concerning reports of Anarchist activity near Avana, Warchief Kabil ordered the summary execution of the monarch on the road between Gawawa and Wasif, sometime between September 11 and 13. News of the execution reached Avana before the end of the month, sparking unrest among the Republicans, with significant concerns that the Warchief of the Republic was growing too powerful. With concerns that a militarist coup could follow if Kabil amassed sufficient support, Karim N'Tsabunar was executed in retaliation on October 1. The news of the execution shocked Kabil, who halted his army in Wasif as the Central Commune Army began to approach Avana.

Anarchist campaign

While the bulk of the Republican Army defeated the Royalists over the summer of 1837, the Anarchists were quickly consolidating control over the major population centres of the country, though aside from the Central Commune Army's decisive defence of Maktarim from several disorganized Republican forces, they remained untested in pitched battle and the bulk of the Anarchist forces were untrained and ill-equipped in contrast with the veteran professionals and mercenaries in the Republican Army. Despite this, the Anarchists were able to mark several major victories including the consolidation of Ifurša with the defeat of the Republican marines in February 1837 and the capture of Haluwaxam in April. The Anarchists may have had difficulty maintaining cohesion over the summer and refrained from any large scale manoeuvers over the summer, benefiting from the Republicans' focus on the Royalists despite Republic support eroding rapidly in the country's major population centres.

When the Royalists were ultimately defeated in fall 1837, the Anarchist leadership was divided in how to proceed, with the Central Commune Army and Papin's Adventurers favouring a rapid advance on the fortified mountain city of Avana to confront the Republican government. The contingent of Black Guards, however, hastened preparations to fortify and defend their positions, preferring the strategy that won their previous battles against the Republic. When news that the Republican Army had stalled in Wasif reached the Anarchists in Maktarim, the Central Commune Army carried the consensus and the Anarchists prepared for their first offensive campaign on Avana. The full Anarchist army that marched on Avana and besieged the city numbered some 200,000 people, including men and women, and some 10,000 professional soldiers in the Central Commune Army. The Republican garrison of Avana counted a mere 20,000 and even the reinforced Republican Army did not exceed 60,000 but had more than twice as much artillery as the Anarchists (23 batteries compared to 11). However, when intelligence reports reached Wasif, it took a full three days before the Warchief of the Republic gave the order to march to reinforce the city.

Second Battle of Avana

The Anarchist forces reached the outskirts of Avana on December 6 and completed an encirclement in three days with a small force. The bulk of the army skirted around the city to block the road to Wasif, taking advantage of the hilly terrain. Warchief Kabil's delay in departing for the capital proved essential for the Anarchists to assume the favourable position, as the Republican Army arrived on December 8, camping across a small valley from the Anarchists. The Republicans were able to position their artillery on the opposing hill across the valley, but neither side had range across the distance that separated each camp. Despite the pressure of the siege on the Republican government in Avana, Kabil chose to adopt a defensive posture, concluding that drawing the attention of the main force of the Anarchists presented the best opportunity for the garrison to break out - which would create the ultimate moment to attack. Despite this plan, Kabil had no means of communicating with the defending garrison. The Republican Army attempted to secret messages to the garrison on the nights of December 9 and 10, but on the first night the messenger was captured and the second defected, each time delivering messages to the hands of the enemy.

On December 11, the Anarchists moved two of their artillery batteries to bombard the citadel of Avana. Unbeknownst to both the attackers and the reinforcing defenders, the bombardment had a profound effect and key members of the Republican government, including the President Zemrassa Waguten, were mortally wounded. With the temporarily weakened Anarchist positions and with no contact with the garrison, the Warchief and his staff elected to assault across the valley on December 12. Republican troop movements began before dawn, rapidly closing the distance between lines in a chevron shaped formation centered on the main road. The numerical advantage of the Anarchists was mitigated by the chosen fronts of the attackers and the disorganization in wheeling the ranks of irregular fighters at each flank to confront the Republicans. However, the remaining artillery batteries were extremely effective in suppressing the movement of the Republican centre and, later in the morning, directing counterbattery fire as the Republicans attempted to move their artillery into position.

The first columns of Republican soldiers exhausted their field supply of ammunition and withdrew by noon instead of closing with the Anarchists where the high ground and numerical superiority could be decisive. The movement back across the valley proved costly, however, and despite the lesser skill of most of the shooters, the Anarchist ranks were able to sustain a substantially greater volume of fire. The Anarchist field commanders decided against pursuing the retreating soldiers but desisted from the bombardment to reinforce their guns and save ammunition. As fighting subsided in the heat of the afternoon and the darkening skies of the evening, the Anarchists used the cover of darkness to reorganize their lines and reposition their artillery in attempt to confound the Republicans' strategy for the next day. Total casualties for the first day of fighting were between 5,000 and 6,000 for the Republicans and between 7,000 and 8,000 for the Anarchists. The Republicans also lost some 35 cannons to counterbattery fire but were able to salvage most of their ammunition.

The second day of fighting saw a similar advance before dawn, this time with Republican soldiers carrying additional ammunition advancing in thin lines screened by cavalry. Despite the shallow depth of the valley, the screen was ineffective at concealing the concentrations of the enemy forces and the location of the Republican artillery. As further attritional combat would be unfavourable for the Republicans, the plan for the day was to lay targeted fire on infantry positions near the Anarchist artillery batteries, allowing for cavalry to charge forward and spike the guns, after which the Republicans could use their artillery advantage to neutralize the field. However, the Anarchists' movements rendered the plans ineffective and Republican tacticians in the field were unable to regroup to find their targets. As smoke from continuous gunfire flooded the valley by noon, Warchief Kabil moved with his staff down into the valley to accompany the main corps of cavalry.

Unlike the previous day, the fighting on December 13 did not subside in the afternoon, possibly due to difficulties in coordinating an orderly withdrawal. As the heat of the day intensified, several Anarchist formations collapsed and fled in disorder, but the numerical superiority and overall high morale allowed for fresh soldiers to replace those who left. As evening fell, the Republican lines began to break as the soldiers began to see their attacks as futile and lacking direction. With ammunition exhausted, the Republican infantry in the centre charged the Anarchist lines, sustaining devastating casualties, while the flanks broke and fled the field. At the end of the day, the Republicans sustained a further 22,000 to 24,000 casualties and the Anarchists between 18,000 and 20,000. The Warchief did not return to his camp after the battle and was never officially identified among the dead, but was never heard from again.

Conclusion

With the defeat of the Republican Army, the garrison at Avana surrendered two days later, conceding the fortress and the surviving government officials to the custody of the Anarchists. By the beginning of 1838, news of the decisive defeat of the Republican Army and the capture of Avana had spread rapidly through the country and abroad. In Munaxdri, the Republican Navy began preparations to escort nobles and merchants who were fleeing the country. The closing months of the conflict saw significant wealth and assets rapidly extracted as the Talaharan elite resettled across the Periclean basin, settling in Latium, Lihnidos, and Sydalon. Others merely crossed the Qeshet to the Tyrian states while some relocated to newly-established Taršiš. The Yisraeli protectorate was unrecognized by the communes which pushed to extend their influence over the traditional boundaries of the country. While tensions and skirmishes erupted with the Yisraeli forces in the protectorate, the assembled representatives of Talahara's communes chose to refrain from forcing the issue, instead focusing on the formation of a new society and defending the country.

The victorious forces of the Anarchists moved divided and spread across the country in pursuit of the remaining Republican forces, with the Central Commune Army pushing eastward against the few remaining strongholds. The last Republican holdouts in Gawawa and Alud were defeated in early June 1838. The end of the war was officially declared at a convention of the wartime Commune Council on June 20, 1838, alongside the establishment of the United Communes of Talahara.

Aftermath

Formation of the United Communes

The victorious Anarchists, faced with the prospect of hostile neighbours and uncertainty, resolved to remain in a united coalition. This prospect was especially a necessity for many rural communes and particularly further in the country's south due to the reliance on trade from the north and presumed hostility from the Awakari Empire, Yisrael, and the neighbouring Tyrian states. The country's various communes dispatched delegates to Maktarim to begin the process of state-building and the drafting of the governing terms and agreements of the union, expanding the Commune Council by hundreds of delegates. The process of drafting what would become the Supreme Consensus took the better part of two years, during which the ideological and political landscape of the country was significantly altered. While major proponents of social mutualism and anarcho-socialism, including Mass Ziri Akli and Kahina Markunda, were included in the constitutional conventions of the Commune Council, the stateless societies they envisioned were rejected on the basis of practicality. The external threats facing the United Communes necessitated systems of organization and coordination to muster a national defence. The conventions also faced a number of oppositional and moderating influences, even as the processes of greater social revolution and the expropriation of private property began to be undertaken commune by commune across the country.

Baligan Amasen, still at the fore of the leadership of the Central Commune Army, was a leading voice in favour of an organized military as the main requirements to ensure the survival of the fledgling country, with the military as the sole organ necessary to protect an anarchist society. However, the militarist faction was regarded with significant suspicion by the rest of the Commune Council due to its origins with the Royalist faction and the elite backgrounds of some members of the officer corps. Concerned with the potential threat that the military posed to the democratic process, the Commune Council dissolved the Central Commune Army within four months of the war's conclusion. Instead of a national military, the United Communes would rely on the Black Guards for national defence and some form of state to interconnect its components. As such, the truly anarchic social mutualist designs for Talahara died a quiet death in the post-war consensus-building process.

The emergent faction within the Commune Council at the beginning of 1839 was the syndicalist movement. Centered on urban industrial workers, the movement called for labour organization as the core element of social organization, with the democratization of labour as the next step to emancipate the working class and provide a system of socialist control over production. The orthodox syndicalist movement suggested that the basic unit of social organization should be the labour union, with either the Commune Council or a successor organization acting as a congress for representatives of the various unions or syndicates. Among the syndicalists were a number of sub-factions with significant philosophical differences: the market syndicalists and the industrial syndicalists. Market syndicalists were among the most moderate movements at the Commune Council, calling for the existing commercial entities in Talahara to be expropriated directly to their workforces and to otherwise engage in a socialist market economy. The market syndicalists were rebuked as revisionist. The ultimate consensus of the Commune Council came down against empowering markets and subjecting citizens to its whims and manipulations as undemocratic. The industrial syndicalists proposed that unions should be organized with whole industries as units of social and economic organization. Effectively, each industry would have a monopoly on its portfolio, connecting workers across the country, but would be subject to checks by the other syndicates and the supply and demand of materials and products. The industrial syndicalist movement was ultimately successful in leading reforms to the economic structure of the United Communes, but did not carry the conventions without controversy.

While the syndicalists held considerable sway over the Commune Council, others feared that the concentration of political power within whole industries could have impacts on personal freedoms, particularly on education, movement, and familial structures. Accusations arose regarding the purported corporatist ordering of Talaharan society and the moderates demanded to put significant checks on industrial power in place. The more radical anarchists in the conventions also argued that industrial unionism as the core political organization would disempower local communes and create barriers to infrastructure and the accessibility of community services including hospitals and schools.

The ultimate synthesis of the constitutional conventions of the Commune Council was the formation of a distinct civic syndicalism, with a representative political system, independent of the industrial unions which would nevertheless make up the core economic system. At a basic level, the communes maintained the residual power to legislate and administer their communities, but with the power to delegate authority to upper levels of a nested council system to coordinate the administration of larger scale services and laws that would only be relevant or practicable at a greater scale, first at regional and then at national levels.

Ex-patriot community

Following the exodus of nobles and merchants from Talahara from 1836 to 1838, significant expat communities developed in other countries around the Periclean. Estimates of emigrants range between 50,000 and 250,000. The bulk of these emigrants settled nearby in Taršiš, the Tyrian states, Gran Aligonia, and some south to Awakar. Other significant Talaharan expat communities were established in Latium, Lihnidos, and Yisrael.

Legacy

As the first self-ascriptive socialist revolution in modern history, the Talaharan Civil War had significant influence through history, with both its events and ideas inspiring politicians and philosophers abroad. The civil war directly inspired the revolutions of 1848 and 1883 in neighbouring Tyreseia, along with other unsuccessful anarchist and socialist uprisings across the second half of the 19th and early 20th centuries. Along with the liberal revolutions earlier in the 19th century, the victory of socialism in a country also served as a cautionary tale for conservative governments around the world. Reactions varied considerably, with some countries gradually developing forms of state welfare to appease simmering tensions with the working classes in a similar context of industrialization. Other countries engaged in brutal repression against peasants and workers.

Major socialist thinkers who were influenced by the civil war include Harrison Werner and Kamikawa Yukichi. The latter was a major figure in the socialist revolution in Tsurushima, which developed a technocratic government based on worker-centred planning. Werner, the founder of orthosocialist communist thought, was a young adult by the war's end and collaborated significantly with his editor and translator Mason Maroon (born Masil Marun), a Talaharan expatriot living in Arthurista.

While the civil war was particularly influential among socialist revolutionaries, others held a negative appraisal of the revolution as a failed attempt to create a truly communist or stateless society. Orthosocialists in particular, including Werner and the mid-20th century Ulwazist movement, criticized the anarchist movement for making concessions to bourgeois forces and failing to establish a dictatorship of the proletariat. Maroon, writing specifically on the conditions of his home country, wrote that authority is a natural force that has to be harnessed by the proletariat, otherwise it is bound to be imposed on the proletariat by reactionaries. Maroon concluded that the syndicalists either naively or subversively disarmed Talaharan workers and thereby gave up the tools to achieve world revolution and the path to a stateless society.