Naming customs in Themiclesia

In Themiclesia, an individual often possesses several names, each for a separate purpose. The manner in which these names are created and used is associated with a large body of cultural traditions and, in some cases, legal prescription.

In most cases, a surname can be combined with another name to give additional information about the person mentioned.

Surnames

Most Themiclesians have two surnames, found on the census.

The sjêngh (姓) is often translated as "inherited name". While it is usually inherited through the father, the etymology of the Shinasthana character, suggests that it is more associated with the female line when the character was invented. This has been interpreted by some anthropologists to indicate a matrilineal society or totem during the earliest phases of Themiclesian culture. The sjêngh was historically used to indicate ancestry, and Themiclesian culture strongly discouraged marriage between two individuals of the same sjêngh, which was thought to lead to inbreeding. To prevent inbreeding, the sjêngh is never altered throughout an individual's life. Traditionally, at no distance in the geneological relationship between two persons is this rule dispensed with; in the modern age, laws have been significantly relaxed, with sibling and first- and second-cousin marriages prohibited.

The gjê (氏), sometimes rendered as "family name", is also passed on through the father. The family name differs from the inherited name in its function as a geographic, professional, or political indicator. There is debate how the gjê originated, some academic works making the case the gjê originally applied to branches of a clan that occupied certain productive niches or held notable positions, not dissimilar to how Western names like "Tanner" or "Smith" appeared. This theory has been expanded to include geographic gjê for branches of a clan that founded or joined settlements and were named after it; as such, unrelated lineages can have the same gjê. While the sjêngh never changes, the gjê may change with an appropriate reason, such as marriage, adoption, moving, or politics. Into the modern period, many gjê are compounded with geographic areas, e.g. the Rje (李, "Plum") of Pjan-ljang (繁陽), who have the sjêngh of Sljeh (姒) instead.

A prominent example of a political gjê is Gwjang (王), which literally means "king". This was the gjê taken up by junior branches of the royal family as they separated from its finances. Thus, rather than being divided geographically, most canonical Gwjangs append their names with their royal ancestor, rather than geographic places, e.g. Gwjang of [King] Mjen of Tsjinh (晉文王氏). Any kind of hereditary title can replace the gjê in writing, as it serves the same purpose of identifying a person with a kinship group; this is often considered evidence for the original use of gjê, more as a social designation rather than the identity of a lineage. Indeed, political titles show a strong ability to become names for lineages. As an example, when the emperor signs treaties, he names himself "Emperor La", (皇帝涂, gwang-tegh-la), even though his gjê is Slje-mra of Gar-nubh (河內司馬); any of his descendants who do not receive titles are likely to take up the name Gwjang, "King".[1]

Personal names

An individual receives his mjeng (名) or personal name at birth, usually given by his parents. Clairvoyants have been known to participate in a child's naming by exaimining the portend of each element of the name in combination with the hours of the child's birth; this practice is now uncommon. A personal name can be one or two characters long, which typically contain a coherent meaning that may or may not be related to the person. In contrast with some cultures, Themiclesian names rarely draw from mythology or religion; instead, objects of cultural or philosphical importance, natural features, and abstract concepts are more popular themes. Most themes relating to war, violence, disease, misfortune, and negative images in general are avoided.

Personal names were thought to bear a supernatural relation to its owner. In antiquity, knowledge of a personal name enabled one to curse the name and thereby its owner; therefore, a courtesy name (see below) was required. It thus became highly taboo and offensive to utter the personal name of another person, particularly that of a social superior; in the case of the emperor, this constitutes the crime of lese-majeste. Personal names, post mortem, are also referred to as "taboo" (諱, hwjeih). Exceptions to this rule are one's own family members and oneself. Conversely, to identify oneself by personal name is deemed an act of humility, probably associated with the ancient belief that exposing one's name was tantamount to exposing oneself.

The system of taboos extended significantly historically. The personal names of a person's parents, grandparents, great-grandparents, and great-great-grandparents are all subject to taboo; the taboo is expected to be observed by visitors in some social segments, who should be informed beforehand of such prohibited words. In modern times, some very traditional individuals still maintain the habit of substituting a different character when writing these taboo words to demonstrate their respect towards their families.

In place of the personal name, a dzjeh (字) or courtesy name was used for most social functions. It was acquired by an individual when he was presented to his community, which could occur during adolescence or early adulthood. As with the personal name, parents are responsible for coming up with a courtesy name. Though it is common to find courtesy names that bear some relation to the personal, it was not a rule. Other elements often augment the courtesy name proper, which usually is one or two characters long.

Within one's family, the canonical format is normally seniority + courtesy name + gender affix. Seniority amongst siblings is with respect to gender; that is, the eldest brother and eldest sister both receive the "eldest" designation. The eldest of either takes the prefix mrangh (孟), which is probably cognate with m′rjang (兄), meaning "elder"; the second takes trjungh (中), cognate with "middle" (中, but trjung); the third and subsequent take tjikw (弔). Male siblings use bja′ (父) or father, and female ones me′ (母) or mother, regardless of their marital status. The seniority prefix can sometimes combine with the word m′rjang (兄) or "sibling" as mrangh-m′rjang (孟兄), "eldest sibling" or trjungh-m′rjang (中兄), "middle sibling".

Beyond the family, the seniority element is typically omitted in favour of the family name, as the person's seniority amongst siblings is usually of less importance to outsiders.

Name changes

In principle, a Themiclesian person may always change his personal name by reporting the change to the bureaucracy. However, his sjêngh and gjê are subject to restrictions; the sjêngh was considered biological in Themiclesia and in no case may be altered until the modern period. If a child with a known gjê is adopted, it may be renamed to that gjê. When a woman marries, she may also change her gjê to match that of her husband, though this was not common practice in the upper echelons of society. Other than these reasons, changing gjê was discouraged or prohibited for convenience of administration.

During the Tsjinh dynasty, the gentry clans began to acquire political and economic rights, such as exemption from upper limits to freehold, the right to retain subsidiary clans, and to participate in triennial civic elections. Originally, whether a clan was part of the gentry or not was socially decided, but during the late 4th century an official register appeared to combat fake ancestries or marriages as a means to obatin prestige. From that time, counterfeiting family trees, marital records, and pretending a gjê to which one did not belong (冒氏, mugh-gjê) became serious offences.

Writing names

In Themiclesian custom, it is typical to give a person's full name and title in the following format.

- Prefecture + gjê + titles + name

Without hereditary titles

For example, the full style of the current prime minister is written in full as

- 內史徐尚書令怡

- i.e. Inner Region Lja, Prime Minister, Le

And after the first mention of his full style, subsequent mentions would usually be abbreviated to

- 尚書令怡 or 怡

- i.e. Prime Minister, Le, or Le

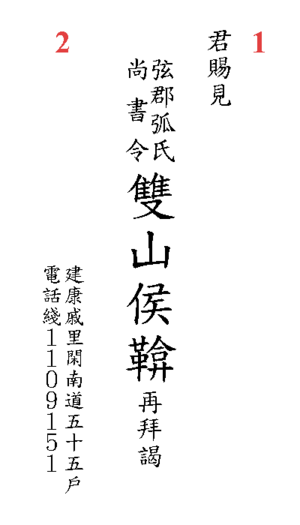

With hereditary titles

According to the rules discussed above, the full style of the 'Ap, Lord of Srong-sngrjar, prime minister between Jun. 1971 to Jun. 1972, is as follows

- 尚書令雙山侯鞥

- i.e. Prime Minister, Lord of Srong-sngrjar, ′Ap

And thereafter abbreviated as

- 尚書令雙山侯 or 雙山侯

- i.e. Prime Minister, Lord of Krungh or Lord of Krungh

In the same vein, the style of the current sovereign:

- 皇帝涂

- i.e. Emperor La

And abbreviated as

- 皇帝

- i.e. [The] Emperor

Though out of respect for the Emperor's personal name, it would be usual to omit it altogether. It should be noted that the descriptor "Themiclesian" (震旦) is never appended to the title "Emperor"; rather, to specify the Emperor's nationality, his subsidiary title "King of Tsjinh" would be used instead.

- 晉王涂

- i.e. King of Tsjinh, La

The composite style below is occasionally seen as well

- 晉王皇帝涂

- i.e. King of Tsjinh, Emperor La

See also

Notes

- ↑ The word "emperor" is, in Western sense, a style of the chief prince of Themiclesia; he is still the King of Tsjinh while using the style "emperor", which properly means "great god" in Shinasthana.