Tabgach (Levilion)

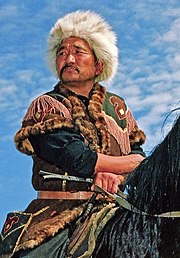

Paintaing of a Tabgach horseman in traditional clothings | |

| Total population | |

|---|---|

| 2 million (2020) | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| Shang Fa | |

| Languages | |

| Buqut, Principean, Huranian | |

| Religion | |

| Predominantly Barukung Macakkanism Minority Perendism |

The Tabgach (拓跋; Tuoba) are a people living in northern Shang Fa and counted among the Tartares, a wide array of non-huranian and non-principean people who share a common nomadic or semi-nomadic lifestyle. The Tabgach are the most numerous group of Tartares and can themselves be subdivided in a number of clans and lineages. They were also the first recorded non-Huranian group to establish their own state within Huran: the Zhao Dynasty which lasted from the late from the 8th to the 12th century. Their influence on Huran would be longlasting, both artistically and culturally: they lead the way for the mass adoption of Macakkanism throughout northern Huran and, by refusing to restore their predecessors infrastructures (canals, aqueducs, granaries, road network...), they effectively turned most of the Great Plain into pastures, allowing for the preservation of a semi-nomadic way of life which became a stapple of northern Huran until the industrial era.

Nowadays, the Tabgachs live mostly in the western parts of theregion known as Northern Tartary, a vast portion of the Great Plain between the Sky Pillars and the Hou river.

Language

The original language of the Tabgachs is of uncertain classification. It is unclear when exactly the Tabgachs adopted a different language and it is highly probable that the process took centuries during which various dialects of different families competed among the tribes part of the Tabgach Confederation, but their modern speech and is safely counted among the Oghuric languages known by the tribe which is said to have first spoken it: the Buqut.

History

The first state

It's during the first half of the 8th century that the Tabgach' presence in the Great Plain is recorded. After a series of low-intensity warfare with the Gao Dynasty, mainly raids and counter expeditions from each sides, the Confederation submitted to the Hegemon-King. They were granted the fiefdom of Zhao (趙國; Zhàoguó) somewhere it what is known today as Tabgachia. Three decades after their settlement, a civil war within the Gao Hegemony allowed the Tabgach to expand rapidly, growing wealthy through mercenary works for the various factions and claimants of the civil war. When the Gao reunited, they immediately attempted to revert the situation and limit Zhao' influence which led the to the Zhao-Gao War in 781. While the Tabgachs lost all lands they had acquired south of the Bian River, they successfully forced the Gao to abandon the Great Plain. The following year Tabgach Huang, prince of Zhao, proclaimed his own Dynasty and took the title of Hegemon-King for himself.

When the Zhao took over northern Huran, it had been devastated by the preceding 27 years of uninterrupted conflict. The collapse of the Gao meant the crumbling of the infrastructures controlling the flow of the Queen River, as well as of the Royal Granaries supposed to limit the effect of any famin. The intertwined war, raids, diseases, famins, floods, droughts, and emmigration meant that the Zhao had access to a very limited pool of workers and taxable subjects to rely on compared to their predecessors.

Rather than trying to restore the previous dynasty' infrastructure and attract back farmers and workers from southern Huran, the Zhao instead turned most of the Great Plains into pastures, adopting a semi-nomadic model while extracting wealth from the remaining Hua cities on the shores of the Queen River in the form of tributes. The political system of the Zhao as often be called Nomadic Feudalism, or "Nomadic Hegemonism".

Through the influence of the Alawokambeses, Macakkanism spread quickly among the Tabgach, merging its cosmology with their own pantheon until it became the de-facto state religion of Zhao. The spread of Macakkanism, despite greatly enriching the cultural life of the Dynasty, would also prove to be Zhao' demise. A new movement within the religion spread across Huran, reaching the non-Tabgach population. While at first these new sects attrated the Zhao aristocracy, chief among them being the School of Moral Order, they ended up being perceived by the Hegemon-Kings as a threat against their authority and waves of persecution were launched against the movement. This resulted in this "New Law" Macakkanism to take the form of a Huranian proto-nationalism dedicated to overthrowing the Zhao. By 1170, the Militant Orders were parading in the Zhao' capital and the Dynasty was all but dissolved.

Kuang Dynasty

The Compromise at Anshan concluded the era of warfare between the newly established Barukung Kuang Dynasty and the Lankung Tabgach remnants with the submission of the latter to the former. The Tabgachs were allowed to keep their religion and to organise their own Free Collegium with their own religious sites and pastures north of Hou River.

The Tabgach would mostly remain absent from historical records until came the Hegemon-Abbot Anman Lizi granted himself the title of Heavenly King. This led to the First Kuang Civil War, won by the "Anmanites", which officially divorced the Collegia from the government of the kingdom. However, this reinforced central administration and destabilized religion placed into question the legitimacy of the Dynasty. Secret societies meant to restore the "Religious-Hegemony" appeared, and played a key role in a second (1266 - 1273) and third (1294 - 1299) civil wars. While rebels all failed in their objectives, they did weaken the effective powers of the central authorities, allowing for the return of a landlord-based aristocracy.

The Aruvian Free Collegium, the religious fiefdom of the Tabgach, first considered itself unconcerned by those events "internal to the New Law' Grand Collegium". But they ended up supporting the Anmanite faction in their political project, mostly out of fear that the collapse of the Kuang Dynasty would allow other new law Collegia to break the Compromise of Anshan and attack them. Ultimately, they became involved in private wars between Collegia, and then between clans as central authority collapsed and peripherical entities took over. It's one of these entities, the Khitan, who would end up spelling the doom of the dynasty.

Khitay and Tegreg hegemonies

The Tabgach quickly allied with the Khitan when they first arrived in the Great Plain and when they entered in open conflict with the Kuang, the Tabgach did not hesitate to join the newcomers' side against their old masters. Yarud Salad, chieftain of the Khitan, thus did not forget to reward generously the Tabgach in land, pastures, cattles, and revenues from the crown.

The establishment of the new Khitay state led to deep changes in the administration of the Great Plain. While the Aruvian Free Collegium continued to exist as a religious institution it was stripped of all political powers by the new Khitan Hegemon-Kings. Instead, the Tabgach tribes were put under the authority of the Northern Administration, the Khitan' office tasked with managing nomadic affairs.

Under the Khitan, the Tabgach maintained their Lankung beliefs in a majority-Barukung state. This did not prevent them from adhering fully to Khitay with their chieftains and princes reaching high positions within the Northern Administration and the military. But as time passed and the Khitan settled new tribes and people from the Steppes inside their country, launching extensive land reforms to weaken both the Macakkanists Collegia and the landed aristocracy, the unity of the nomadic and semi-nomadic people was replaced by court intrigues and dynastic conflicts within the bureaucracy of the Northern Administration. This culminated in 1540 with the uprising of the recently settled Tegreg people, joined by Tabgach generals and entire tribes. The Tegregs successfully overthrew the Khitan and established their own Dynasty: the Yuan.

Because of their violent takeover, the Yuan never managed to stabilize their rule. Intense court conflicts, mistreatement of their allies, and disregard of their supporters led to Tabgach tribes that have remained neutral and even a majority of those that had originally sided with the Tegreg to abandon them and return to the Khitan to form a new confederation and rise in revolt. But ultimately, a new revolt rose up led by the Huranian Li Sheng, a bureaucrat-turned-warlord who successfully defeated a number of Tegreg armies. Many Tabgach ended up joining Li' revolt and they convinced their clans and their tribes to do so as well once it became clear Li Sheng had become the new hegemon of the Great Plain. A situation made official when he established his own state in 1571: the Lin Dynasty.

Northern Administrators of the Lin Dynasty

Li Sheng adopted the dual administration of the Khitan for his own dynasty and de-facto granted the control of the Northern Administration to the main Tabgach lineage: the Dulo clan of the Buqut. It's under the Lin Dynasty that the slow convertion processus of convertion of the Tabgach people, encouraged by their own nobility wich wished to better integrate itself to the distinctly Barukung and Huaner society of the Lin. The last Old Laws holdouts, known as "Aruvites", would die out sometime during the 18th century.

It's during the Lin Dynasty that Auressians first arrived in Huran, establishing trade ports and missions on the coastline under the strict overwatch of Imperial Supervisors. But while the Lin Heavenly King had de-facto granted the Northern Admnistration to the Tabgach clans, they would also lose most of their powers on the Southern Administration to the gentry clans and scholarly families they relied on for their administration. This led directly to the Tan-Zheng Disorder (覃鄭亂; Tán-Zhèng Luàn) so named after the two main gentry clans vying for control of the royal court. The Disorder also affected the Tartares, with the Khitan siding with the Tan and the Tabgach joining forces with the Zheng, closer to the royal court.

But in the 1740s began a minor Hua farmers rebellion that would prove capable of defeating the troops sent to crush it and establish their own Kingdom. Led by the three Ruan Brothers, the rebels waged war against the Zheng clan, their direct overlords. In 1750, the rebels took over the Lin' capital, overthrowing the dynasty. The Tabgach, needing allies for their conflict with the Khitan, submitted to the Ruan Brothers and their new Hong Dynasty where they tried to maintain the dual administration of their predecessors.

But the Hong didn't last long before falling into dynastic infighting and court intrigues. Fortunately for the Tabgach, the Khitan began their own internal tribal conflict at the same time, nullifying their threat. Some Tabgach clans attempted to support one Khitan faction or the other, but the majority had grown tired of the civil strife. Dulo Batar, the last Northern Prime Minister of the Lin and Hong, was deposed and his partisans isolated as the Tabgach reformed into an independent Confederation, unconcerned with the troubles of the Khitan and the Huranians. When the Tan clan defeated the Hong Dynasty with the help of their Khitan and Principean allies, the Tabgach confederation simply recognized this new Dynasty.

Tan Dynasty

For their submission, the Tabgach leadership was granted various courtly titles from Tan Yandi the new Heavenly King. Tügren Nohreb, chieftain of the Confederation for example, was granted the title of Duke of the Tabgach and he was recognized as administrator of what would become known as Tabgachia. However, only a fair few Tabgach, ones with both experience in the previous Northern Administrations and no ties to the current dominant clans, were given positions within the Northern Administration which would be dissolved anyway a few years after the creation of the Dynasty, replaced by a singular Central Administration.

Tan Mingdi, son and successor of Tan Yandi, wish to get rid of foreign influences within his country led to civil war when Viceroy Dujue proclaimed that Mingdi' nephew was the legitimate monarch. Khitan and Tabgach ministers and officials for the most part simply fled the court to return to their home regions where their Principalities became de-facto autonomous if not outright independent. Tügren Armaï, eldest son of Tügren Nohreb, did not hesitate to depose his elderly father with the support of the Confederation so that he could proclaim the creation of a Kingdom of Tabgachia. Ultimately, Armaï would accept the offer of Hua-Principeans to join their Grand Covenant where he became one of the Four Great Kings (the Kings of the Tabgachs, Khitans, Manchus, and of Bian).

Great Covenant

The Covenant represented a Economic and monetary union as well as a joint military to which all member states needed to contribute men, but only the Tan Dynasty, the Bian Kingdom, and the Principean League were required to participate in its finances. While at first the control of the Covenant' institutions was balanced between its constituent members, after 54 years of existence they had all been taken over by the Principean League, from the military to the diplomacy. When Paul Moisson, a Principean Odoque who was campaigning for reforming the system and for a better integration of the non-Principean and non-Huranian people, was murdered in December 1860 the Great Tartares Kings left the Covenant and formed a League of their own. Nonetheless, the League quickly found itself incapable of presenting a coherent front, divided between the Nationalists, the pan-Tartarists, the Monarchists... by 1866, the Principeans no longer had to manage many other fronts and were now both outnumbering and outgunning the Tartares. The last pockets of resistance would be crushed in 1868.

While their Monarch was forced to abdicate, many Tabgach clans found solace in Armand Dupic, the new strongman and leader of the Principean League, promises of integration, social elevation, and wealth redistribution. They would all be present at the coronation of Armand Dupic as Hegemon King (霸王; Bà Wáng) in 1871 and would be greatly rewarded by their new patron with military and civil positions within his new administration.

Modern days

Today, the Tabgach remain the largest Tartare group with an estimated 2 million people living mostly across an ensemble of twelve principalities. Although, knowing the exact number of Tabgach in Shang Fa is made impossible by the state' policy of not keeping ethnic census. Thus all information about their demography and their geographical distribution come from independent third parties observations and extrapolations of linguistic data and questionnaires on self-identifications.

The cultural area known as Tabgachia is ill-defined. Its "core" is made up, north-to-south and west-to-east, of the Prefectures of Dai (代國, dàiguó), Forges (煅爐, duànlú), Epolie (馬皇, mǎhuáng), Bassine (水盆, shuǐpén), and Tressalie (索州, suǒzhōu).

Alongside these Prefectures there are others which may or may not be counted as part of Tabgachia depending on personal opinions. Those are, to the north, the Tianzhu prefecture of Ernobrige (鹰巅, yīngdiān) which historically was part of Tabgachia but is today mostly inhabited by Principean-born Languan "Blue Caps" living in Garrison towns deep in the valleys. To the west, the prefecture of Ariovarède (馬主, mǎzhǔ) is shared, population wise, with the Khitan (Levilion) but is otherwise fully integrated into the nomadic and semi-nomadic lifestyle of the rest of Tabgachia. Finally, to the west, there's the prefecture of Gorge (溝壑, gōuhè) which is generally considered to be part of the Upper Minjak geographical region but is also the home of many Tabgach settled communities who live mainly from Mining and metallurgy alongside a very diverse settlers population.

The last space of Tabgach habitat is the geographical area traditionally known as Wei made up (once again from west-to-east and north-to-south): Creuset (盆地, péndì), Muret (圈地, quāndì), Tourraine (魏州, wèizhōu) and Digue (水壩, shuǐbà). This region, inhabited in its majority by Huranian people, is also the traditional home of the Tabgach landed aristocracy, owning vast agricultural exploitations in the countryside and forming the local, Huranized, urban elite living in a typical Huaner lifestyle, halfway between the nomadic steppe culture and the urban culture of the Hua.

Like other Tartares, the modern Tabgach are divided between those keeping up the nomadic lifestyle, those having settled in rural hamlets to cultivate crops but mainly to practice Animal husbandry. Tabgach clans were notably famed for their horses and ironsmithing. After the industrial revolution, many of Tabgachia previously purely administrative centers grew exponantially under the influence of trade and the railways while small hamlets turned into cities of their own due to the boom in demand for mineral ressources. This development was mainly fueled by the influx of Hua and Principean people from the Great Plain rather than by the Tabgach own demographic growth which resulted in many tensions and conflictual relations.