Tenerians

ⴽⴻⵍ ⵜⴻⵏⴻⵔⴻ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 23,900,000 | |

| 18,900,000 | |

| 3,080,000 | |

| 665,000 | |

| 240,000 | |

| 175,000 | |

| 150,000 | |

| 40,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Tamashek | |

| Religion | |

| Ashni Addin | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Other Amaziɣs | |

The Kel Tenere (Tamashek: ⴽⴻⵍ ⵜⴻⵏⴻⵔⴻ), also known as the Tenerians, are an Amaziɣ ethnic group of nomadic origin indigenous to central Scipia and the Ninva desert. They have historically inhabited parts of Talahara, southern Tyreseia, parts of Alanahr and the whole of Charnea. The term Kel Tenere translates to "People of the Desert" and is used by the Tenerians to differentiate themselves from the non-Amaziɣ ethnic groups in the modern day Charnea. Today most of those who self identify as Kel Tenere are have become urbanized and transitioned to a modern sedentary lifestyle, while a minority have retained the ancestral condition of nomadism and continued to live in the open desert with few modern comforts. Although both urban and nomadic Tenerian people inhabit all the regions of Charnea, the urban subculture is termed the Kel Aɣrem or Aɣremites while their nomadic cousins are termed Kel Ajama or Ajamites to signify their rural status. The ancestral Kel Tenere united under a powerful chieftain Ihemod the Inheritor, who went on to establish the Charnean Empire in the latter half of the 14th century.Today, a significant portion of those who are considered Tenerian in the modern day are of Ikelan origin, the descendants of slaves taken by the Charneans during the Ihemodian conquests who subsequently assimilated into the Tenerian culture. In the modern day, Tenerian society and culture is deeply defined by its role within the nation of Charnea as the centerpiece of national identity and as the principal component of ethno-linguistic assimilation of internal and external immigrants.

History

Origins

The Tenerians, as with all Amaziɣ groups, find their origins in the ancient proto-Amaziɣ polity of Tamazgha which streached across much of modern day Talahara and western Charnea. The people of Tamazgha were a settled culture practicing agriculture through the use of advanced irrigation techniques to tap the subterranean fossil water reserves under the Ninva desert. The fall of Tamazgha, referred to in Charnea as the "Lesson of Ekelhoc", was perpetuated by the drop in the aquifers on which the Tamazigh cities relied leading to the collapse of the political confederation and the fracturing of the Amaziɣ people into distinct groups. Those who moved to the north of the former Tamazgha, towards the more arable coast and remained sedentary agriculturalists became the ancestors of the Talaharan groups, while those who remained in the Ninva desert became the ancestral Tenerians. The Kel Tenere thereby trace their origins to the fall of Tamazgha in late antiquity, an occurence which scattered their ancestors across the Ninva and motivated their transition to a pastoralist lifestyle gaining sustenance mainly from herds of camels and goats capable of surviving where crops such as flax or barley could not.

This early Tenerian society placed great significance on the membership of individuals within a structure of clans and of castes within those clans. This development was closely tied with the transition to a nomadic lifestyle, as the extended kinship group, the clan, became the primary unit of society. At the top of the social hierarchy were the nobles of the clan, in particular the heads of the main lineages and those families who served as their vassals. The noble caste were the only ones allowed to carry weapons such as takobas, spears and bows, and would be responsible for protecting the clan and its herd from rivals and predators. The vassals were primarily responsible for tending to the animals which served as the main source of sustenance. Below them, an artisan class worked leather, wood and metal to craft weapons, tools, clothing and other items needed in the camp. Finally, the lowest rung of the early Tenerian society were the Ikelan, the slave caste which lived in semi-sedentary conditions tending the crops of the clan's limited agricultural activities as well as mining the materials needed by the artisan class. During this era, the Ikelan were primarily other Tenerians captured from rival clans during raids, and only occasionally were foreign war captives. The clans were organized into political confederations of their own, with several clans taking part and electing an Amenokal to serve as paramount chieftain. Major confederations included the Kel Atram, the Kel Ajej and the Kel Awakar, which would last from the mid 1st millennium to the eve of the Teralwaq in the 1350s.

Ihemodian Era

The Teralwaq, the famine and turmoil produced by the Siriwang Eruption and the subsequent volcanic winter, promoted the rise to power of Ihemod the Inheritor. Ihemod was a former slave of the Kel Awakar who had become the protégé of the confederation's Amenokal. Ihemod would go on to seize power within the Kel Awakar, coercing the clans across the polity to join his cause and waging a brief war of unification across the Ninva desert to bring the other Tenerian tribes under his control. The great famine of the Teralwaq was the main driver of the unification, as Amenokal Ihemod believed the Tenerian people would not survive unless they could invade more fertile lands. This set off the Ihemodian wars, which would see the united Tenerian confederation called Kel Kaharna wage a war of subjugation against many of the peoples of Scipia. Ihemod reorganized the Tenerians into into decimal units of tens, hundreds and thousands of fighting men with their families becoming camp followers on the military campaigns of the Kel Kaharna. Noblemen, vassals, artisans and Ikelan alike were pressed into military service, given weapons and for the first time gained status through merit and loyalty in service rather than through relationships of blood and patronage.

As the Tenerian people waged wars of conquest across the continent, they became an increasingly militarized society. Every able bodied Tenerian male served in Ihemod's army of the Kel Kaharna for several years, with the traditional pastoralist lifestyle largely falling by the wayside in this period. The women, children and old men of the clans would be mobilized along with the fighting men in support of the roving army of the Tenerians, foraging and assisting around the nomadic camps in the field. This was made possible by the looting of cities and capture of large numbers of war captives to join the Ikelan slave caste and work in mines, in agriculture and in tending the herds to sustain the purely military society that the Tenerian nomads had transformed into. In this way, the internal divisions between the Tenerian castes were eliminated through their merging into a single military caste, while the external division between the Tenerians and their subjects and Ikelan slaves widened as the economic role of the Ikelan grew and the income from plundering the conquered lands for wealth became more prominent.

Awakari Empire

Following the decline of the Charnean Empire within a century of Ihemod's death, the social dynamics of the Ihemodian era and the height of Charnean power in Scipia began to evolve. As the rump state of Ihemod's once continent-spanning empire, what remained of the Charnean state was politically hollowed out by the military leaders of the great clans that had risen to prominence in Ihemod's service. This left the urban core in Agnannet and the figurehead Amenokals of the Empire on the political sidelines, with the Amghar clan leaders living a nomadic life in the expanses of the Awakar in the central Ninva holding true power, giving this middle period of the Charnean Empire is name as the "Awakari Empire". The government of the clan leaders was generally conservative and opposed significant reform, preserving the social structure of the Ihemodian era in many respects, particularly in maintaining a separation between the pure-blooded Tenerians who led the great clans who were involved in mercantile and military pursuits from the mixed Ikelan class represented the main productive demographic of society and produced the food, materials and mineral wealth which sustained the nomadic upper class. This was complicated by the gradual Tenerization of the Ikelan who were almost exclusively of non-Amaziɣ origin prior to the enslavement of their ancestors during the Ihemodian wars. Ikelan had been purposefully settled with other Ikelan of different ethnic and religious origins and who spoke different languages as a means to frustrate attempts to organize resistance against the Tenerian overlords, but this had the additional consequence of alienating the Ikelan from their original cultures and turning the Tamashek language into the lingua franca of the Ikelan, which put pressure on the remnants of original culture surviving in the Ikelan communities. Over time, these conditions corroded away most connections to long lost homelands the various Ikelan from all across Scipia may still have held, turning most Ikelan into Tamashek-speaking people which had largely adopted the ways of the desert-dwelling Tenerians as a natural consequence of living among them deep in the Ninva for centuries. By the 18th century, most Ikelan thought of themselves as being no different than the Tenerians, speaking the same language and worshipping the same gods. This redefined the social conflict between the largely sedentary Ikelan and the nomadic Tenerians from a conflict between Tenerians and subjugated outsiders to a class struggle within Tenerian society, in which both sides identified themselves as Tenerian people.

Modernity

The end of the Awakari era ushered in the age of industrialization and modernization across the Charnean Empire. The reforms which came about with the downfall of the great clans and the Imperial Restoration Movement of the 1910s and 1920s largely did away with all systemic and legal segregation between the nobles Tenerians and their Ikelan counterparts. The urbanization which came as a necessary step to bring the industrial revolution to Charnea saw the wealthiest of the sedentary Ikelan peasant families along with the more savvy of the old noble clans becoming more powerful players in the capitalist mode of production of the new Charnean economy. The wealth of the new Charnean society of the early 20th century remained concentrated in the great city of Agnannet and to a lesser extent Azut, Hamath and Ekelhoc, which in turn prompted hundreds of thousands of nomadic and semi-nomadic Tenerians from across the Ninva desert as well as rural Ikelan living in small agricultural communities to migrate into the urban centers and settle there, creating for the first time an industrial proletariat. The transformation of Charnean society placed a tremendous strain on the water rescrouces of the desert nation, leading to significant internal conflicts over control of the water supply in which rural populations, especially unintegrated minority populations, were dispossessed by the new capitalist class and the reformed Charnean Army also known as the ICA. The remaining nomadic population of the Ninva desert, which had become disenfranchised from the newfound wealth of the industrial era in a reversal of the prior centuries, became the main source of manpower for the ICA to fight in the rising conflicts of the early 20th century due to the lack of any real employment opportunities available to the native Ninvites.

Industrialization and the wars of the 20th century created and solidified the modern divide between the urban Kel Aɣrem and the rural or nomadic Kel Ajama within the Tenerian demographics of Charnea. The population of Aɣremites rise significantly, propelling the major Charnean cities first to hundreds of thousands and later millions of Aɣremite Tenerian inhabitants who have adapted to their newfound urban lifestyle and mixed their nomadic heritage with the more cosmopolitan identities of the great cities and of the primarily Aɣremite Ikelan Tenerians with their mixed ethnic origins. Most of the Charnean population of Tenerians today are Aɣremite Tenerians, and this demographic contributes a near-totality of all economic activity in Charnea. Conversely, the Ajamite population shrank in comparison to their urban brethren precipitously in the first half of the 20th century, and became increasingly insular due to their isolation from the new urbanite culture. In many ways, the modern Ajamites represent a recreation of the militarized society of the Ihemodian era, with most Ajamite men serving in the ICA at some point in their lives and the artifacts and traditions of the Ajamite nomadic culture seeping into the military culture in Charnea, while the militarization of the majority of the Ajamite population would likewise introduce many practices, references and ideologies into the culture of the Ajamite Tenerians.

Subgroups

Kel Ajama

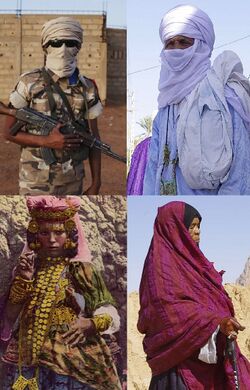

The Ajamite Tenerians are the descendants of those Tenerian nomads who did not settle in the great cities and retained their pastoralist lifestyle in the rural areas of the Ninva desert. As a result of the high rates of poverty and few employment opportunities available to these nomads once Charnea had industrialized, large numbers of these nomad Tenerians joined the Charnean Army to make a living. The military considered the Ajamites highly desirable as recruits, as their nomadic lifestyle acclimated them to survive in the wilderness and to navigate the desert landscape, further increasing the number of recruits of nomadic background in uniform. Through the decades, the Kel Ajama became deeply intertwined with the Charnean Army, with their traditional lifestyle becoming warped by the mass recruitment and indoctrination of the nomads into military service through multiple generations. By the time of the Ninvite War in the mid 1980s, nearly the totality of the Kel Ajama had been raised by a member of the Charnean Army since nearly every family had at least once ICA veteran, and a large portion had been raised in or around Army bases. In many ways, the nomadic society of the Kel Ajama adapted to their militarization favorably. The alienation from the civilian society of the urban Charneans and social isolation due to frequently moving around between military bases during childhood were factors which were already present within Ajamite communities due to their growing separation from the Kel Aɣrem. The elevation of status associated with the soldier's profession and the bearing of weapons grew as an organic extension of the old Tenerian warrior culture instilled in the nomads since the days of Ihemod. Conversely, the deepening division between the militarized Kel Ajama and their urban cousins has only served to create greater segregation between the two, with many Kel Ajama facing significant social pressure both from within their community and from outside to pursue a military career in the case of men or to support their male family members' military careers in the case of women. This has served to limit the social mobility of many Ajamite Charneans and prevent many from entering into higher paid fields with higher education requirements, despite the lack of any significant legal or institutional barriers.

Many aspects of the old pastoralist culture have been preserved and carried forward by the Kel Ajama, despite the transition of the majority of their society away from the profession of animal husbandry. This is most evident in the diet and cuisine of the average Ajamite, which remains rooted in the "blood and milk" food culture of the old Tenerian nomads. This diet is based on the ancient practice of milking and bleeding animals to create meals of milk, yoghurt, cheese and coagulated blood without killing any member of the herd, while meat which could only be taken from animals too old to be bled or milked as well as bread or vegetables which could only be gathered at certain times of the year or through trade with outsiders were reserved for special occasions and for the elite of society. Bread, in particular flatbread made of millet grains or mesquite pods, has become a much more significant portion of the Ajamite diet compared to their ancestors of centuries past, while meat has remained a relative scarcity due to the rarity of animals raised primarily for meat in Charnea which was driven up the price of the camel, goat and cow meat preferred in Tenerian cuisine. The Kel Ajama are also known to wear the litham, the traditional Tenerian male veil, in contrast to the urban Kel Aɣrem which have largely abandoned the practice. This is the origin of the term "veiled man" as a shorthand for a member of the Charnean Army, where the practice of the men veiling themselves is beleived to be tolerated due to the anonymity and sameness it confers to its wearers as well as its evocation of the feared Tenerian warriors of Ihemodian times.

Kel Aɣrem

Aɣremites are the most numerous Tenerian subgroup by far, making up more than half of the entire population of Charnea. The bulk of the modern Aɣremite population are the descendants of the Ikelan slave caste of medieval Charnea, descended from Anahri, Punic Tyreseian and Amayana as well as Amanite and Hadarite Talaharans taken as war captives in Ihemodian times and settled in what is now modern Charnea. An additional contingent of the Aɣremites are made up of those Tenerian nomads who migrated to the cities during the era of Charnean industrialization in search of work and a livelihood, as well as the Zarma people displaced and drawn to the great cities in the aftermath of the Agala War. These diverse ethnic backgrounds as well as the greater contact with the outside world that came with life in the industrialized cities of Charnea created a diverse urbanite culture for which the Aɣremites are known today. The greatest influence on the culture of the Aɣremites has been the transformation of the majority of their numbers into the Charnean industrial proletariat through the introduction of the capitalist mode of production to the great cities of Charnea. This has resulted in the rapid mutation and alteration of the cuisine, clothing, religion and cultural traditions of the Aɣremites from their nomadic or agriculturalist origins to a distinct culture of Charnean city-dwellers. Bread, meat, processed foods, sugary products and fish were introduced into the diet of the Kel Aɣrem thanks to their greater access to the wider Scipian market through the railroad connections of the great cities, radically altering the old Tenerian blood and milk diet of the nomads as well as the traditional cuisine of the Ikelan farming settlements. While certain local staples such as millet cereals and date fruits remain in place into the modern day, much of the consumption of camel milk and especially the consumption of blood as food has declined sharply among the Aɣremites compared to the old Tenerians, although blood-based dishes remain a delicacy.

The living habits of the Kel Aɣrem have likewise been changed by their transformation into an urban proletariat. Aɣremites live almost exclusively in apartments within large housing towers characteristic of Charnean cities, where limitations of space often place pressure on families to inhabit many different apartments. In the early 20th century at the beginning of the urbanization process, it was commonplace for several apartments to share facilities such as a kitchen, a bathroom and a common living area in part as a means to extend the old communal living habits of the Tenerian clans to the urban environment. However, this practice was ultimately ended as the bonds of clan began to break under the social pressures of the new environment, with most modern Aɣremite Charneans living only with immediate family in apartments separate from the rest of the extended family.

Kel Dinik

The Kel Dinik, better known as the Eastern Tenerians, are a minor subgroup of the Tenerian population in Charnea who settled in the traditionally non-Amaziɣ regions of the Charnean east. They are considered to be neither Kel Ajama, as their settlement in the east involved the loss of their pastoralist lifestyle and splitting off from the old nomads of central Charnea, while they are also not considered to be Kel Aɣrem as they adopted the sedentary lifestyle many centuries before Charnean industrialization and remain a primarily rural agriculturalist demographic. Despite being part of the Tenerian majority in wider Charnea, they are considered to be a local minority as they are greatly outnumbered by the Deshrian Copts and the Hatherian Gharib communities of the east. Close contact with the varied cultures of the east have created a highly divergent Kel Dinik dialect of Tamashek and brought many outside influences into their culture. Kel Dinik Tenerians face significant stigma and segregation within this region and have been historically shunned by their non-Amaziɣ neighbors, frequently being singled out and targeted for anti-Tenerian reprisals in response to transgressions of the predominantly Ajamite Charnean Army against local demographics. The Kel Dinik are the only Tenerian subgroup which is not primarily Ashniist, being predominantly Coptic Nazarist with some groups adhering to the Azdarin faith, causing them to be shunned by other Tenerians on religious grounds.

Diaspora

Rubric Coast

Alanahr

Mutul

The Divine Kingdom is home to the largest Kel Tenere community outside of Scipia. They live mostly in the cities of K'alak Muul and Puylum, with smaller communities scattered across the east coast of the Mutul. Tenerians have reached the Divine Kingdom since Charnea began syncretizing and converting to the White Path in the modern era, but emigration really took off only in the late 20th century and early 21th. Sharing a religion with their host country has allowed the Tenerians (called తెనెహె, Tenej, in Mutli) to rapidly gain subject status and integrate into the Mutulese society compared to other migrant community.

Part of the Tenerian immigration is linked to service in the Divine Army of the Ninety-Nine Nations, where they represent an increasingly large proportion of the recruits as veterans often decide to settle permanently in the Mutul than return in their home country. While only a minority, these Tenej often represent leading figures in their communities, serving as various local administrators and representatives of the Mutulese institutions, from the administration to law enforcement, around which a clan-like network of clients can be built. The majority of Tenerians who integrate into Mutulese society in this way are of Ajamite Tenerian origins.

While the Tenej do not represent the entirety of the people of Tenerian-descent in the Mutul, some second or third-generations Tenej having fully integrated themselves into the Mutli culture and no-longer self-identify as Kel Tenere while parts of the immigration has yet to even acquire the subject-status, they are its most representative sub-culture in Oxidentale. While women slowly re-take their traditional role within the society, notably by serving in the Clergy or as political representatives, Tenej communities are still characterized by the control exercised by veteran soldiers as previously stated, shifting ever-so-slightly the traditional gender roles. Tenej' practices of the White Path are also more Orthodox than those in Scipia, and play an even stronger role in daily life. The gun culture of the martially inclined Tenej have however been thoroughly stamped out by the Mutul' strict anti-gun laws. To compensate, martial arts, such as Mik'abe or Muk'yah K'ik, have become especially popular, alongside the religious institutions tied to their practice.

Culture

Language

The only surviving Tenerian language in the modern day is Tamashek, a language originating with the historical Kel Awakar confederation in central Charnea. In the distant past, most Tenerian confederations possessed their own dialect or distinct variation of the root Amaziɣ language. However, through the homogenization and standardization which occurred under the Charnean Empire, the diversity of the local languages was lost and only the Awakari Tamashek variation remained as the standard version across the Empire. Because of Tamashek's status as a lingua franca for many of the diverse ethnic groups residing in Charnea, many loanwords from the native languages of these non-Tenerian peoples have been adopted into common use in Tamashek, such as the Gharbaic word "sooq" meaning marketplace or the Zarma word "kaaruko" meaning horseman. The Academy of Tamashek Culture (Tamashek: Asinag n Tussna Tamashek, ⴰⵙⵉⵏⴰⴳ ⵏ ⵜⵓⵙⵙⵏⴰ ⵜⴰⵎⴰⵛⴻⴽ) headquartered in Agnannet serves as the linguistic authority over Tamashek, and collaborates with language organizations in Talahara over matters of Amaziɣ language and education.