Tula Secunda

Tula Ixchilco Ixchilco | |

|---|---|

| 100 BC–726 AD | |

|

Glyph Banner | |

| Status | City state hegemony |

| Capital | Ixchilco |

| Government | Unknown |

| Historical era | Antiquity |

• Established | 100 BC |

| 726 AD | |

| Area | |

| 1rst century BCE | 17 km2 (6.6 sq mi) |

| 5th century CE | 25 km2 (9.7 sq mi) |

| 8th century CE | 10 km2 (3.9 sq mi) |

| Population | |

• 1rst century BCE | 50,000 |

• 5th century CE | 150,000 |

• 8th century CE | 2,000 |

Ixchilco, known to the Palatinates historians as Tula Secunda was an ancient city-state located in modern day Karazawa, in a valley of the modern day northern Erechi Mountain Range. At its height, Ixchilco was home to an estimated 125,000 people, one of the largest cities of its time. It is remembered today for its many pyramids, some being the largest of Karazawa, and the main rival to the Palatinate, blocking the expansion of the latter eastward. Apart from the pyramids, the city is also anthropologically significant for its complex, multi-family residential compounds and its vibrant murals that have been well-preserved.

No written document from Ixchilco is known. Instead, historians are limited to the texts left by Palatins historians and monuments or stelae left by the vassals of the city. The totonacs claim to have been the founders of the city, but it had clearly become multicultural by the first century CE, and the exact nature of its rulership is still subject to debate among specialists.

Name

The exact etymology of the name "Ixchilco" is hotly debated, but it seems to be from the totonac verb "to see". Ixchilco might then mean "Place of the visions", in reference to the city's nature as a religious center.

As a hegemon in the political landscape of the Conitian antiquity, Ixchilco was referred to as a "Tula" by both its vassals and rivals. The name "Tula Secunda" was specifically used by Palatins Historians to distinguish it from the other "Tula" that existed at the time. The exact correspondence between Tula and Ixchimilco was not proven until 1942, when excavation in the city of Ewa led to the discovery of a stelae written in both Latin and Ewaguatl, copy of a treaty between the Palatinate and the kingdom. In this document, Tula Secunda is clearly identified as Ixchilco, answering the question of the historians.

History

Origins and foundation

The early history of Ixchilco is quite mysterious and the origin of its founders is uncertain. Around 900 or 800 BCE, people of the valley began to gather into larger settlements. It marks the transition between the Nomadic Agriculturalism that had previously dominated the hinterlands of the Erechi Peninsula. The builders of the city took advantage of the geography of the Tollan Valley : from the swampy ground, they constructed raised beds, creating high agricultural productivity despite old methods of cultivation. This allowed for the formation of channels, and subsequently canoe traffic, to transport food from farms around the city.

The Tollan valley was seemingly shaken by violent conflicts between these early city-states but of these, nothing is known. Some of the settlements were destroyed and replaced by Ixchilco colonies, others were greatly reduced and put under the city's control. The nature of said control is also hotly debated : some arguing that the political class of these defeated cities was replaced by governors and officers from Ixchilco and those who defend that it was a purely tributary relationship. But by 100 BCE, no large settlement beyond Ixchilco is mentioned in the Valley.

Expansion and consolidation

The exact details of Ixchilco expansion are unknown, as it was already a well established hegemon by the time the first historians started to take an interest to it. It seems to have first been an important religious center for the northern Erechi Peninsula, and then have gained status as a trade hub through the control of goods like obsidian and iron tools. Ixchilco's wealth thus made it the natural "patron" of many smaller settlements and other cities, protecting them in exchange of favors.

This economic and demographic growth led to a period of expansion, but it doesn't seems that Tula Secunda established colonies. Often, and generally with the support of local rebel factions or of political factions, the sons of important Ixchilco families were put at the head of defeated cities, mixing their traditions and customs to those of Tula Secunda. When revolts against the authority of these new leaders happened, they were crushed without mercy. Massive enslavements are thought to be the main nature of the repression, but the exact details have once again been lost, left unrecorded by the Ixchilcos themselves and untold by later foreign chroniclers.

Ixchilco proper's rapid growth seems to have been supported by the massive immigration of subjugated and allied populations to the city. At its height, Ixchilco had one district for each ethnies under the city's influence : Nuu Davi and Ben Zaa from the north, Totonac from the west, and Nanhu from the mountains to the east and south.

Ixchilco and the Palatinate

The conquest of Tula Prima by the Palatinate in 50 BCE would have went relatively un-noticed from Ixchilco if it wasn't for the migration Nahuatl speakers away from the Palatinate. They settled in modern southwest coast of Karazawa, calling themselves Ewaguan and formed the kingdom of Ewa, which itself became the center of an important network of alliances and dependencies. But it seems that Ewa was itself a distant vassal of Ixchilco, having received support from the northern city, notably in military equipment and training leading to the adoption by the Ewaguans of the war chariot, a distinctive Ixchilcan weapon.

Despite early successes at defending themselves against the Palatins, Ewa was ultimately destoyed by the Palatinate in 70 CE, forcing the Ewaguans to move northward into Ixchilco territories, where they were dispersed among various principalities. The conflict between Ixchilco and the Palatins now became direct. The city of Ewa was abandoned in 90 CE by the Latins, but wasn't resettled. Instead, the general area was left to be settled by various smaller tribes and people, generally speaking uto-aztecan or oto-manguean languages. These principalities served as buffers between the two empires.

Culture

Archaeological evidence suggests that Ixchilco was a multi-ethnic city, with distinct quarters occupied by Otomi, Zapotec, Mixtec, and Nahua peoples. it is generally believed that the original builders of the city were speaking a language related to the Totonac–Tepehua languages. A common theory is that the Ixchilco peoples mark the separation between the Totonacs and the Tepehuas, with the latter migrating outside of the valleys to settle the large coastal plains while the former stayed in the mountains. But it's also currently maintained that the largest population group must have been of Otomi ethnicity, because the Otomi language is known to have been spoken in the area both before Ixchilco foundation and after its fall.

Religion

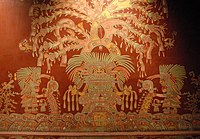

The main deity of the city was named the Magna Mater by the Palatins historians. The dominant civic architecture is the pyramid. Politics were based on the state religion; religious leaders were the political leaders. Religious leaders would commission artists to create religious artworks for ceremonies and rituals.The artwork likely commissioned would have been a mural or a censer depicting gods like the Magna Mater or the Feathered Serpent.

Human sacrifices were practiced. Human bodies and animal sacrifices have been found during excavations of the pyramids. Scholars believe that the people offered human sacrifices as part of a dedication when buildings were expanded or constructed. The victims were probably enemy warriors captured in battle and brought to the city for ritual sacrifice to ensure the city could prosper. Some men were decapitated, some had their hearts removed, others were killed by being hit several times over the head, and some were buried alive. Animals that were considered sacred and represented mythical powers and military were also buried alive, imprisoned in cages: cougars, a wolf, eagles, a falcon, an owl, and even venomous snakes.

Stone masks are also known to have played a role during rituals, both for the priesthood and for the sacrificed. Stone or jade masks were used to represent the ancestors of the deceased during burial and were worn by family members. Something the Palatins chroniclers linked to their own practices of mortuary masks and Oscilla. Metallic masks, of silver, gold, or bronze, also became popular during the late period of the city.

Population

was a mix of residential and work areas. Upper-class homes were usually compounds that housed many such families, generally between sixty and eighty. Such superior residences were typically made of plaster, each wall in every section elaborately decorated with murals. These compounds or apartment complexes were typically found within the city center. The lakes of the Tollan Valley provided the opportunity for people living around them to construct productive raised beds from swampy muck, construction that also produced channels between the beds, easying the transport of goods and people. Different sections of the city housed particular ethnic groups and immigrants. These groups generally retained their languages, customs, and culture, making Ixchilco an inherently cosmopolite city.

Architecture

Tula Secunda adopted massively for its public architecture the Talud-tablero, or slope and panel style. consists of an inward-sloping surface or panel called the talud, with a panel or structure perpendicular to the ground sitting upon the slope called the tablero. It was especially used for pyramids and other religious buildings. Through its expansion, conquests, and political influence, the city exported this style to the rest of the areas under its control, popularizing it and making it a staple of South-Lazarene Architecture.

Most of the city's public monument were built in granite and marble. Beyond these impressive construction, Ixchilco's culture put an emphasis on collective inhabitations, with even the houses reserved to the aristocracy being able to hold around sixty families inside them. Such residences were built out of granite and marble too, while the lower classes' inhabitations were built out of wood and/or bricks.

Mural paintings were extremely common, especially in the wealthier areas of the city. These paintings show a typical use of red paint, complemented on gold and jade decoration.

One of the most impressive construct of the city is an underground network of tunnels and artificials caves that run under the pyramids, centered around the Main Pyramid above. These caves had miniatures mountaineous landscapes with pools of liquid mercury representing lakes, while the walls and ceiling of the tunnels were found to have been carefully impregnated with mineral powder composed of magnetite, pyrite, and hematite to provide a glittering brightness to the complex, and to create the effect of standing under the stars. All of this as a peculiar recreation of the underworld. Above, the great plaza in front of the Main Pyramid show signs of deliberate flooding, as a re-enactment of the Creation Myth, with the Pyramids serving as the primordial mountains emerging from the chaotic waters.