Xu Ti Na

Tĩ Ná̤ | |

|---|---|

| |

| Personal | |

| Born | 1897 |

| Died | 11 February 1961 (aged 63–64) |

| Religion | Buddhism |

| Senior posting | |

| Based in | Naikang |

| Period in office | 1917–1961 |

| Ordination | 1917 |

| Post |

|

| Cause of death | Burns from a house fire |

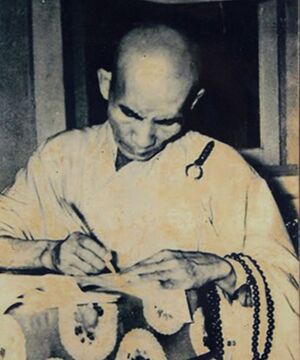

Xu Ti Na (Naichinese: Xũ Tĩ Ná̤, [ɕu᷉ tʰi᷉ nɘ́], 1897 – 11 February 1961) was a Naikanghi Buddhist monk and activist who was a leader in the Naikanghi nationalist movement between 1935 and 1950. Perhaps the best known Naikanghi activist who was not a member of the Ashang in the leadup to the Lotus Revolution, Ti Na was an advocate for peaceful coexistence, inter-ethnic dialogue and peaceful protest, which made him a prominent alternative to the Ashang for those who found their positions too strong.

Ti Na participated in and led marches and public prayers advocating for equal rights and justice for Naikanghi political prisoners. During police reprisals against Ashang-led protests in and around his pagoda of Ngaci, he offered shelter, food and medicine for protesters. As Chairman of the Panel on Naikanghi Ceremonial Rites, he was also influential in the process of reconciling many of the traditionally pagan Naikanghi with the sizeable minority of buddhists present in Naikanghi society, which Ti Na saw as an important step on the creation of a multi-national state in Naikang. At perhaps the peak of his positive public image, he led a walk from Ghenngan to Tachusi, with many Chengshengese and Naikanghi walking the trail in unity.

In the leadup to the Tatchossey Conference, Ti Na was chosen as a key representative for the Naikanghi people. With the Ashang barred from attending due to previous less peaceful protest, many of their desired reforms, as well as those of many Naikanghi nationalists, were not met. With the ban on paramilitaries extending into the formation of the State of Naikang in 1950, Ti Na was also pressured into running for President in the 1950 presidential election, though due to decreasing popularity and numerous smear campaigns later agreed by most historians to have been largely baseless, as well as systemic barriers against Naikanghi people voting and participating in that election, Xu Ti Na won only four percent of the vote. Facing outright hostility from many, Ti Na opted to retire from public life in late 1950, resigning his position as abbot of the Ngaci pagoda and retiring to a rural temple.

In the early years of the Naikangese Civil War, Ti Na broke his silence and advocated openly for peace. Numerous works attributed to him from this period exist, with varying degrees of veracity. Ti Na was found dead in the charred remains of his residence on the morning of 11 February 1961. Many suspect that foul play was involved in his death, though no formal investigation has conclusively discovered any truth to this claim. Xu Ti Na remains a somewhat controversial figure in Naikang even to this day, the almost universally positive favour he enjoyed in the 1940s having all but eroded away by the beginning of the 1950s, and though some modern efforts attempt to rehabilitate him as a man before his time and an advocate for peace in the middle of a brewing conflict, others regard him as a puppet of the Chengshengese and Riamese who attempted to lessen Naikanghi influence on an independent Naikangese state.

Early life and education

Monastic life

Activism

Public image

Retirement and death

Early retirement

Civil War

Writing and attribution

Death

On the morning of 11 February 1961, commotion erupted around the village in which Ti Na now resided as smoke was seen pouring out of his house. As people around the village collected water from the river, the fire grew into a raging inferno, with attempts to approach the house and check inside of it made impossible due to the heat. Most had believed that Ti Na had already made his way to the pagoda by this point, as there were no signs of struggle from inside the house. Attempts were thus redirected to ensuring that nearby houses did not catch fire.

By midday, the fire had subsided, and the charred remains of the house were safe to approach. It was only then, as two Naikanghi farmers from the village first entered the building, that it became clear that someone had been inside the house. When it was confirmed that Ti Na had not gone to the pagoda that morning (though it was not unusual for him to attend later on in the day during his later years), the body was all but confirmed to be that of Ti Na.

Funeral and aftermath

Ti Na's body was covered with an orange sheet and he was brought out to a waiting coffin. The body was charred beyond recognition, but many from the village and beyond came out to see the body and pay respects. One man who claimed to have been housed and cared for by Ti Na in Ngaci in the aftermath of some Ashang-backed protests spoke at his funeral, and the service was performed by the local abbot. His body was re-cremated outside the village, and his ashes were placed into an urn, with the intention of spreading the ashes in Ngaci Province after the Civil War ended. These plans would never come to pass, as the village was attacked merely a month later by troops loyal to the State of Naikang, and the ashes became lost.

News of Ti Na's death quickly spread to both sides of the ongoing Civil War, though reactions remained muted. Purportedly, a few members of the leadership in the Ashang expressed private regret for Ti Na's death, though no public statement was ever released. In Tachusi, the government of Cheq Iangsu outright refused to comment on the matter at length, calling Ti Na "a hermit of little note or repute".

Theories around death

Numerous conspiracy theories exist around Ti Na's death, largely involving questions of how he died and whether other players were involved. Some at the time suggested that Ti Na's death may have been a suicide, though the supposed positioning of Ti Na's body (according to the sole eyewitness who testified at an inquiry in 1976) would have made suicide very difficult.

One theory that has very little traction is that the Ashang, angry over Ti Na's inadequate representation of Naikanghi interests at the Tatchossey Conference, had him killed and staged to look like an accident. This appears unlikely, as the most reputable supposed work of Ti Na speaks of the Ashang in a far more flattering light than he ever had previously.

The far more common theory is that Ti Na was executed by individuals loyal to the State of Naikang, potentially even Riamese special forces, and then the fire was started to cause confusion. There are numerous issues with this theory that cause it to remain unlikely. For instance, the village in which Ti Na resided was some distance past the front lines of the conflict, within Ashang-controlled territory. Moreover, though military actions in Naikang at the time tended to follow rule by decree from Cheq Iangsu, and while Cheq had mentioned assassination of some members of the Ashang leadership, Xu Ti Na had seemingly never caught his attention for long enough to allow for any form of planned retribution. Thus, many Naikanghi conspiracy theorists tend to dwell on the idea of Riamese special forces causing his death, citing that the attack, to have not drawn suspicion, would have to have been quick, stealthy and organised, all signs of a Riamese attack rather than one by the Naikangese army.

Numerous theories have been proposed and investigated at length, though the majority of official and formal investigations uncovered no instances of foul play. It has also been suggested, however, that the later attack on the village was a co-ordinated effort to retrieve the ashes of Ti Na, and stop them from being used as propaganda or for Ti Na to be presented as a martyr.

Legacy

Xu Ti Na's overall reputation and legacy was a topic that, even in the latter years of his life, he never discussed at length. The closest he came was an interview in 1951, just after he retired, in which he said cryptically "I did what I did". This phrase became the name for a notable biography of his by Chan Qha Xu, in which Qha Xu argues;

[Xu] Ti Na knew that his actions would make him many enemies, but fundamentally, he was not a man who gave too much mind to the opinions of those around him. It is the difficulty of researching such a man - his words are intended for his own ears, his own mind, alone. To try and consider them as an outsider, one must try and inhabit his mind, which is almost impossible to do.

Xu Ti Na, despite himself being Naikanghi, received a decidedly negative press by many contemporary Naikanghi in the years up to and after his death, including prominent members of the Ashang. Many blamed him for not further fighting for Naikanghi rights in the Tatchossey Conference, with some going so far as to actually blame him for the entire Naikangese Civil War. This view is not particularly common in the modern day, with many scholars asserting that the selection of Ti Na as delegate for the Naikanghi was only ever a token gesture, and that the Riamese never intended to listen to Naikanghi demands for the structure of an independent Naikang. It is largely among these determinists, who believe that the results of the Tatchossey Conference were predetermined, that Ti Na has the least blame placed upon him from the Ashang. Aside from the nationalists of the Ashang, Ti Na's perception is largely dependent upon his personal impact and those who valued his message of unity between Buddhists and pagans. Many who remembered his acts of kindness to Ashang wounded tend to stress that point in discussions of him, while many Buddhists believe that he can be almost singlehandedly thanked for the fact that Naikanghi nationalism has no explicit religious bent.

Among Chengshengese people, Ti Na's perception is even more neutral. As an abbot, he has been respected by some, and some valued that he attempted to fight for peace, though in a major part, many Chengshengese regard him as little better than the Ashang in practice.