Yajawil of Hamik

Yajawil of the Hamik Islands Hamik Yajawil | |

|---|---|

|

Flag | |

| Motto: Peace and Faith | |

| Anthem: In the shadow of the Mare | |

| Capital and | Rahui’o’a |

| Official languages | Mutli Te Heo |

| Ethnic groups (2016) | Mato people Oxidentaleses people |

| Demonym(s) | Hamikians |

| Government | Absolute monarchy |

| Legislature | Hamik Ch'ob |

| Hamik Sajal Ch'ob | |

| Hamik Mam Ch'ob | |

| Province of the Mutul | |

| Population | |

• 2018 estimate | 200,000 |

• 2016 census | 198,787 |

The Hamik Yajawil is one of the duchies of the Mutul and includes the following islands :

- Hamik peten is the largest island in the Yajawil of the same name and the most westward territory of the Mutul. It's the administrative, political, and economic center of the archipelago.

- Pararu peten is directly to the northeast of Hamik and share a common history with it. It’s the center of the Pararu Kuchkabal, which is still ruled by the old royal family of the Ma’o who hold the position of Halak Winik.

- Tu’ua peten, a small island located to the east of Hamik and Pararu, at about the same distance from each.

Etymology

Since it’s settlement by humans, Hamik Island beared many names. For the Mato peoples, the island is known as Vāhahe, “Grand Seashell”. During the Race to the East, the Zhous called it Yuandao, “Remote Island”, and the Tsurushimeses knew it as Owarishima, “End Island”. The modern official name, Hamik Peten, means “Island under the Wind” and was given by the first Mutuleses traders who sat foot on the island because it was often swept by the oceanic winds that allowed for trans-Makrian travel.

Geography

Of the three islands, Hamik is the highest and largest, followed by Pararu and then Tu'ua. The archipelago is located 4000 km to the northweast of the Mutul, and 3270km to the east of Belfras.

Hamik Island cover an area of around 1000km². The highest point is Mount Harani which rise to 2,100m. The island has been compared to a dumbbell, with two roughtly round similarily sized portions centered on volcanic mountains linked together by a large isthmus named after the Rhoni District which is located on its northern side.

The interior of the island is almost entirely inhabited. These mountaineous inlands are encircled by a main road, roughtly following the old Causaway built by the Mutuleses authorities, which cuts between the mountains and the sea. Almost all of the population live on the coastline, especially around the capital of Rahui’o’a.

Climate

November to April is the wet season, the wettest month of which is January with 13.2 in (340 mm) of rain in Rahui'o'a. August is the driest with 1.9 inches (48 millimetres).

The average temperature ranges between 21 and 31 °C, with little seasonal variation. The lowest and highest temperatures recorded are 16 and 34 °C, respectively.

History

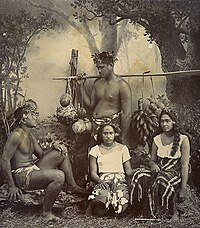

The Mato are polynesians people whose ancestors arrived in the archipelago in 700 AD after a long migration started a thousand years before from the Kahei Islands. This emigration, across several hundred kilometres of ocean, was made possible by using outrigger canoes that were up to twenty or thirty meters long and could transport families as well as domestic animals.

Before the arrival of the Zhou and, later, of the Mutuleses, the main island of Vāhahe was divided into different chiefdoms, very precise territories dominated by a single clan. These chiefdoms were linked to each other by allegiances based on the blood ties of their leaders and on their power in war. Of these clans the Rahui were traditionaly the strongest. They were made up of three different groups : the Western Rahui (Rahui To’o’a), the Eastern Rahui (Rahui Nu’a) and the Mountain Rahui (Rahui Mou’a).

A clan was composed of a chief (Ari’ Nui), nobles (Ari'i) and under-chiefs (Hui To’ofa). The ari'i, considered descendants of the gods, were full of mana (spiritual power). They traditionally wore belts of blue feathers, symbols of their power. The chief of the clan did not have absolute power. Councils or general assemblies had to be called composed of the ari'i and the Hui To'ofa, especially in case of war.

Each district or clan was organised around their Mare, or stone temple, around which were centered both the social and religious lives of the clan.

First Tsurushimese visit

The Hamik Islands were first discovered by the Tsurushimeses’s Eastern Expeditions. They exchanged gifts with the various clans of the islands, establishing the first contacts with them, notably the Rahui. Tsurushima would continue to maintain contact with the Hamik Islands, exchanging gifts and even collecting plants and animals during some expeditions.

The Ochraneses expeditions in Hamik led to the strengthening of certain clans over others, because they controlled harbors greatly favored by the foreign traders. The Rahui were one of these clans, even if their power was contested by the Matauh and their allies. The rivalry between the two clans continued, with sometime interventions from the Ma’o of the nearby Pararu island. Ultimately however, the Rahui would win the war and start collecting tributes and gifts from all the clans of the islands while the Ma’o would do the same on their own, smaller, island. The Ari’ Nui Rahui, Terii-a-mana, took the name of Du, and the title of Ari’ ri'i, founding a new dynasty known as the Tuo.

After the Ochraneses

With the end of the Race to the East, the Tuo would lose the source of their power and face many rebellions, notably by the Matauh and the Rhoni, cutting the island in half again. The last Tuo ruler, Du III, would be forced to abdicate and was replaced by a new elected Ari’ ri'i, starting the House Apatoa who would continue to claim and fight for the complete control of the island. This election would provoke a civil war between the partisans of the Tuo and of the Apatoa. The Apatoa would win the civil war, but lose against the Rhoni clan who came to profit from the chaos. The Rhoni found themselves the direct hegemon of the Rahui clan and of all their old vassals, which provoked the ire of their Matauh allies. The Rhoni would win this second war, and then their own Ari Nui would take the mantle of Ari ri’i, starting the dynasty of the Nehetuo.

Arrival of the Mutul

The first Oxidentalese to see these islands was Akutze Selenecha. But he did not land on them. It’s only when B’alamb’ Kan, the first Mutulese to take the Makrian Road with the purpose of trading and exchanging goods, landed on the island that Mutulo-Hamikians relations truly started. B’alamb’ Kan used the old port of Rahuiri’o’a ('Bay of the Rahui') as his base in the region, using it as a resting place before further expeditions toward the rest of the Makrian Ocean and ultimately Ochran.

In 1535, B’alamb’ Kan’s family was given ownership of the port, which became a Trading Post and the Nehetuo thrived with these new exchanges. However, clanic tensions did not decrease and while the Nehetuo made it illegal for anyone not part of the Rhoni clan to buy iron weapons and firearms, smugglers either from the Ma’o controlled island of Tu'ua or by unscrupulous investors in Rahuiri’o’a led to the constitution of secret clanic militias, the more subversives of which, like the Matauh clan, were conspiring to put an end to the Nehetuo rule. The marriage of the Ari ri’i Mahae III with Meketa, a Rahui princess, in 1541, sealed the alliance between their two clans. The Rahui clans were allowed to buy and own their own firearms, and their militias were integrated into the very young Nehetuo army. The same year, the port of Rahuiri’o’a was elevated to its own “District” and offered to the Mutuleses traders, as a way to definitively win their support.

To show his power, Mahae III would start in 1544 a war with the Ma’o chiefdom to take control of the island of Tu’ua, which was an important hub for the smugglers who undermined the Nehetuo regime. Despite important casualties in both sides during a naval battle, the army of the Nehetuo managed to raid the island and destroy most of its installations, but couldn’t take hold of it. Despite this, it would from there on out be referred as a “private possession of the Ari ri’i” in official documents, even if the Ma’o dynasty would continue to claim ownership over it.

This display did not calm down the potential rebels. In 1547 skirmishes between the Rhoni-Rahui troops and rebels multiplied. Mahae III fled his capital district to find refuge in Rahui’o’a.

The Treaty of Rahui’o’a signed in 1548 established the Nehetuo monarchy as a Protectorate of the Mutul. The same year the local militias employed by the Mutuleses traders would lend their forces to the Rhoni-Rahui and pacify nearby clans, notably securing and occupying the roads between Rahui’o’a and the Rhoni District. The Mutulese army directly intervened in 1549 and troops landed on the island. By the end of the year most of the rebel clans had been defeated and their leaders, generally from the Matauh and the Apotoa clans, were ritually sacrificed.

In 1553, a second port, K’arahe was built as a purely military base for the Mutuleses fleets. The newly created Makrian Fleet then sailed toward Hamik peten. This was the start of a campaign of “pacification” during which the Mutul raided Tu’ua a second time, before blockading and attacking Pararu. After the Battle of Pararu, the Mutul and the Mo’a Monarchy signed the treaty of Maharepa in which the “Moha Ajaw” agreed to the protection of the Mutul, to be included in the “Market System” and to cease war with the Nehetuo, abandoning all claims on Tu’ua as a sign of goodwill.

Between 1560 and 1568, the Mutul organized the construction of a long Causaway linking together all the Mare, sacred places, of the islands.

In 1598, Oë II, Ari ri’i of Hamik, went on a journey to K’alak Muul to swear allegiance to the K’uhul Ajaw. When he returned to Hamik peten in 1600, it was with the title of Hamik Yajaw and a certain number of privilege. With the help of the Admiral of the Makrian Fleet, Oë II reorganized his island : he moved his capital to Rahui’o’a while he named his brother “Halak Winik” of the island, directly supervising the clanic districts, renamed “Batabils”. The smaller groups that made up a clan were also renamed “Lakamnahob” ; “Great Houses”. The Makrian Fleet's Admiral was also tasked with negociating the final pledge of alliegeance of the Ari ri’i of Pararu. The island was therefore fully integrated into the Mutul too, and the Ari ri’i Mo’a became an Halak Winik in the Mutulese hierarchy, placed under the authority of the Hamik Yajaw.

To finish the complete administrative reform of the island, the third and final island of the archipelago, Tu’ua, was elevated from personal possession of the Nehetuo Dynasty into its own Kuchkabal, led by its own Halak Winik, the first of which was the second son of Oë II. Since that time, the archipelago has known little administrative re-arrangement.

Economy

Hamik is one of the poorest Yajawil of the Mutul. Tourism is a major component of the local economy, attracting people from Ochran, Oxidentale, and more rarely from Norumbria and Belisaria.

Agricultural activities are a minor part of the archipelago's economy. The main crops cultivated are the sweet potato, Chaya, and fe’i banana, but also tomatoes, avocadoes, taro, many kind of fruits… a chicken farm exist on Hamik island and produce meat and eggs for the local market. Cash crops include vanilla, Copra, Noni, ylang-ylang… Sylviculture is also an important source of revenue. Meanwhile, Pararu island is renowned for its ananas.

Fishing is a major sector of the economy. In 2010, the port of Rahui’o’a exported 400 tons of fishes for a value of 2,5 millions solidus. Many private and public investments have, since 1989, helped the development of the port and of the industry as a whole, notably with the installation of Fish Aggregating Devices around the island. Alongside it, Pearl farming is also a substantial source of revenues.

Despite all of this, tourism is still the main activity of the island, receiving between 150,000 and 200,000 visitors a year. As a result, the tertiary sector represent around 60% of the island’s GDP and is the main source of employment, alongside governmental jobs with the naval base of K’arahe and the public administration.

Hamik Yajawil has one of the highest unemployment rate in the Mutul, with 13% of the workforce unable to find a job in 2018, concerning especially younger generation. This situation has led to the creation of a Mato Diaspora in continental Mutul, with many Mato or Hanikians in general leaving the archipelago to find work on the mainland. On top of this there are many Mato students who have decided to pursue their studies outside of the archipelago because of a lack of opportunities. As a result, around 50,000 Mato peoples currently reside outside of the Yajawil, uually found in Western Mutul's ports cities.