Military dictatorship in Etruria: Difference between revisions

Tag: Undo |

|||

| Line 65: | Line 65: | ||

== Background == | == Background == | ||

Etruria's political crisis stemmed from the inadequacies of the new political system constructed in wake of the [[Solarian War]], through the [[Community of Nations Mandate for Etruria]]. In an attempt to limit the influence of the security establishment and reinforce checks and balances, the [[Senate of Etruria]] was granted far-reaching powers and oversight over security policy. The failure of the post-war governments to equalise the pace of reconstruction across all states of the federation, allowed the festering and growth of separatist and far-leftist movements in [[Carinthia (Etruria)|Carinthia]] and [[Novalia]]. The post-war political system massively limited government responses to security crises, with deployments of police, the auxiliary gendarmes and regular military dependent upon votes in both houses of the Senate. This inability coincided with a wider sense of declinism across all Etruria, with the country gripped by post-war poverty, criminality and corruption. The {{wp|social decay|social}} and moral decay perceived to be undermining Etrurian society, also led to a resurgence in support for right-wing and far-right parties and a general openness to authoritarian rule, if only to see the country’s course changed. | |||

Etruria's political crisis stemmed from the inadequacies of the new political system constructed in wake of the [[Solarian War]], through the [[Community of Nations Mandate for Etruria]]. In an attempt to limit the influence of the security establishment and reinforce checks and balances, the [[Senate of Etruria]] was granted far-reaching powers and oversight over security policy. The failure of the post-war governments to equalise the pace of reconstruction across all states of the federation, allowed the festering and growth of separatist and far-leftist movements in [[Carinthia (Etruria)|Carinthia]] and [[Novalia]]. The post-war political system massively limited government responses to security crises, with deployments of police, the auxiliary gendarmes and regular military dependent upon votes in both houses of the Senate. | |||

[[File:Fernando Tambroni-1.jpg|260px|thumbnail|left|President Massimo Bartolucci consistently refused to violate the constitution to meet the security crisis in the western states, alienating business leaders, the military and many in the general public.]] | [[File:Fernando Tambroni-1.jpg|260px|thumbnail|left|President Massimo Bartolucci consistently refused to violate the constitution to meet the security crisis in the western states, alienating business leaders, the military and many in the general public.]] | ||

The emergence of secessionist movements in the western states first came about in the early 1950s, as these states saw significant inequalities in reconstruction and re-development compared to [[Vespasia]]. The use of {{wp|proportional voting}} | The emergence of secessionist movements in the western states first came about in the early 1950s, as these states saw significant inequalities in reconstruction and re-development compared to [[Vespasia]]. The use of {{wp|proportional voting}} at the federal and state level, and the inability for the threshold to be increased from 3%, forced parties to enter complicated coalitions to form stable governments. The [[Democratic Worker’s Party]] had entered government in 1950 alongside the [[People’s Liberal Party (Etruria)|People’s Liberal Party]] and [[Sotirian Democracy (Etruria)|Sotirian Democracy]], the former having ties to separatist parties in Carinthia and Novalia. The PLP was also one of the most forceful opponents of securitisation and militarisation in the federal legislature. Not only did this significantly reduce the federal government's ability to respond to the amassing of weapons by separatist militias, but further limited law enforcement's ability to investigate. The [[Democratic Action Party]] government (1948-1957), which drew many of its leading figures from the Community of Nations Mandate, refused to adopt harsh measures against separatist elements, go as far as to defend their rights under the constitution, alienating unionists in the centre-right and the military. | ||

[[File:Tambroni Genova scontri.jpg|200px|thumbnail|right|Street fighting in Dubovica during the negotiations between President Bartolucci and separatist groups.]] | [[File:Tambroni Genova scontri.jpg|200px|thumbnail|right|Street fighting in Dubovica during the negotiations between President Bartolucci and separatist groups.]] | ||

In | In 1952, the [[Novalian People’s Liberation Front]] was formed out of a grouping of Solarian War veterans. The NPLF attracted the attention of the socialist bloc in Euclea and was provided safe havens in [[Piraea]] and [[Amathia]]. The election of the centre-left [[Democratic Worker’s Party (Etruria)|Democratic Worker’s Party]] under President [[Ferdinando Grillo]] in 1953 did little to stem the growth of nationalism in Carinthia and Novalia. The same year, the various left-wing nationalist groups in Carinthia united to form the [[Combatant Front for Carinthian Liberation]]. In response, numerous pro-Etrurian nationalist movements rose up in response, including the [[Black Unionists]] and the [[National Volunteer Defence Front]], by the end of the year both sides were clashing in running street battles across Carinthia and Novalia. In 1953, state elections in Novalia saw the [[Farmers and Workers Union]] led pro-Etrurian alliance win most seats in the state legislature, pushing the Novalian nationalists toward armed insurrection over democratic means of securing independence. That year, the NPLF attacked six police stations and army bases, distributing weapons and munitions to supporters. Similar actions took place in Carinthia, sparking the [[Western Emergency]]. | ||

From 1953 until 1960, the nationalist armed groups would limit their attacks and operations, often just retaliating against unionist groups such as the NVDF. The violence further limited the degree of reconstruction and economic progress in both states, while the violence undermined the DWP government in [[Povelia]]. The violence, the wider sense of declinism among Etrurians, the stagnant economy and rampant corruption also provided a vital space for the resurgence of far-right politics at the national level. In the 1958 election, the [[New Republic Movement (Etruria)|New Republic Movement]], a neo-functionalist party that advocated military action against the growing nationalist threat won over 35 seats. The inability by the central government to face the escalating violence in the west and the further refusal to call out foreign support drove many senior figures within the Etrurian armed forces to begin planning a seizure of power to protect national unity. On February 19 1959, the NPLF bombed the railroad connecting Vilanja to Drostar, causing a train to derail and leaving over 100 people dead. The next day, the Etrurian Armed Forces began to deploy forces without government permission, the subsequent political struggle saw the government acquiesce, empowering the generals who stepped up plans for a seizure of power. | |||

== Capitoline Accord and fall of the Second Republic == | == Capitoline Accord and fall of the Second Republic == | ||

Revision as of 13:23, 20 August 2020

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

United Transetrurian Federation Federazione Transetruriana Unita Sjedinjene Prekoetruriska Federacija Združena Čezetruriska Federacija | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960-1983 | |||||||||

Motto:

| |||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||

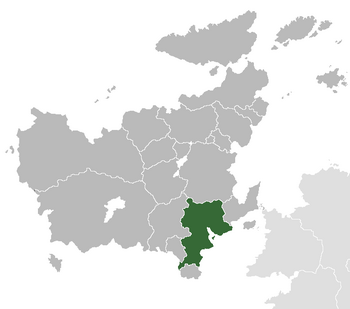

Etruria in green. | |||||||||

| Capital | Poveglia | ||||||||

| Government | Federal authoritarian military dictatorship | ||||||||

| Chief of State | |||||||||

• 1960-1974 | Francesco Augusto Sciarri | ||||||||

• 1974-1978 | Giovanni Aurelio Brocco | ||||||||

• 1978-1983 | Gennaro Aurelio Altieri | ||||||||

| Premier | |||||||||

• 1960-1974 | Guilio Cesare Tulliani | ||||||||

• 1974-1978 | Enrico Povegliano | ||||||||

• 1978-1983 | Alessandro Galtieri | ||||||||

| Legislature | Consultative Assembly | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 14 May 1960 | |||||||||

| 1 July 1983 | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1968 | 47,102,444 | ||||||||

• 1978 | 53,656,771 | ||||||||

• 1983 | 56,339,781 (estimate) | ||||||||

| Currency | Florin | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Etrurian military government was the authoritarian military dictatorship that ruled Etruria from 4 May, 1960 to 1 July, 1983. It began with the bloodless constitutional coup of President Massimo Bartolucci—and ended when Miloš Vidović took office on 1 July, 1983 as President. The military overthrow of Bartolucci was backed by the near entirety of the Etrurian officer corps and the Supreme Command of the National Armed Forces (Commando Supremo), who had lost faith in the democratic government to confront the Western Emergency.

The military dictatorship lasted for almost twenty-three years; despite initial pledges to the contrary, the military government, in 1963, enacted a new, restrictive Constitution, and stifled freedom of speech and political opposition. The regime adopted nationalism, economic development, and Anti-Collectivism as its guidelines.

Background

Etruria's political crisis stemmed from the inadequacies of the new political system constructed in wake of the Solarian War, through the Community of Nations Mandate for Etruria. In an attempt to limit the influence of the security establishment and reinforce checks and balances, the Senate of Etruria was granted far-reaching powers and oversight over security policy. The failure of the post-war governments to equalise the pace of reconstruction across all states of the federation, allowed the festering and growth of separatist and far-leftist movements in Carinthia and Novalia. The post-war political system massively limited government responses to security crises, with deployments of police, the auxiliary gendarmes and regular military dependent upon votes in both houses of the Senate. This inability coincided with a wider sense of declinism across all Etruria, with the country gripped by post-war poverty, criminality and corruption. The social and moral decay perceived to be undermining Etrurian society, also led to a resurgence in support for right-wing and far-right parties and a general openness to authoritarian rule, if only to see the country’s course changed.

The emergence of secessionist movements in the western states first came about in the early 1950s, as these states saw significant inequalities in reconstruction and re-development compared to Vespasia. The use of proportional voting at the federal and state level, and the inability for the threshold to be increased from 3%, forced parties to enter complicated coalitions to form stable governments. The Democratic Worker’s Party had entered government in 1950 alongside the People’s Liberal Party and Sotirian Democracy, the former having ties to separatist parties in Carinthia and Novalia. The PLP was also one of the most forceful opponents of securitisation and militarisation in the federal legislature. Not only did this significantly reduce the federal government's ability to respond to the amassing of weapons by separatist militias, but further limited law enforcement's ability to investigate. The Democratic Action Party government (1948-1957), which drew many of its leading figures from the Community of Nations Mandate, refused to adopt harsh measures against separatist elements, go as far as to defend their rights under the constitution, alienating unionists in the centre-right and the military.

In 1952, the Novalian People’s Liberation Front was formed out of a grouping of Solarian War veterans. The NPLF attracted the attention of the socialist bloc in Euclea and was provided safe havens in Piraea and Amathia. The election of the centre-left Democratic Worker’s Party under President Ferdinando Grillo in 1953 did little to stem the growth of nationalism in Carinthia and Novalia. The same year, the various left-wing nationalist groups in Carinthia united to form the Combatant Front for Carinthian Liberation. In response, numerous pro-Etrurian nationalist movements rose up in response, including the Black Unionists and the National Volunteer Defence Front, by the end of the year both sides were clashing in running street battles across Carinthia and Novalia. In 1953, state elections in Novalia saw the Farmers and Workers Union led pro-Etrurian alliance win most seats in the state legislature, pushing the Novalian nationalists toward armed insurrection over democratic means of securing independence. That year, the NPLF attacked six police stations and army bases, distributing weapons and munitions to supporters. Similar actions took place in Carinthia, sparking the Western Emergency.

From 1953 until 1960, the nationalist armed groups would limit their attacks and operations, often just retaliating against unionist groups such as the NVDF. The violence further limited the degree of reconstruction and economic progress in both states, while the violence undermined the DWP government in Povelia. The violence, the wider sense of declinism among Etrurians, the stagnant economy and rampant corruption also provided a vital space for the resurgence of far-right politics at the national level. In the 1958 election, the New Republic Movement, a neo-functionalist party that advocated military action against the growing nationalist threat won over 35 seats. The inability by the central government to face the escalating violence in the west and the further refusal to call out foreign support drove many senior figures within the Etrurian armed forces to begin planning a seizure of power to protect national unity. On February 19 1959, the NPLF bombed the railroad connecting Vilanja to Drostar, causing a train to derail and leaving over 100 people dead. The next day, the Etrurian Armed Forces began to deploy forces without government permission, the subsequent political struggle saw the government acquiesce, empowering the generals who stepped up plans for a seizure of power.

Capitoline Accord and fall of the Second Republic

In anticipation of the impending declarations of independence, the Supreme Command moved up plans to remove Bartolucci from office and declare a state of emergency. The Supreme Command was headed by General Francesco Augusto Sciarri, who for years had held significant disdain for the post-war constitution and political system. He viewed the failure or rather constraints on the federal government to confront separatism as a long-term intention of the post-war elite. Following the meeting at Villa Espirito Santo, he secured the backing of all senior commanders in the Army, Air Force and Navy to stage a coup. On May 1, he and six other senior commanders agreed the layout of the post-coup government and deployment to the Western States.

In the early hours of May 4 1960, the Etrurian Army deployed approximately 6,800 soldiers to metropolitan Poveglia, from the 2nd Military Region under General Amadeo Vincenzo, sealing off the Poveglian Causeway and surrounding the homes of prominent government ministers. At 3.54am, soldiers entered the Palazzo Vittoria on Saint Andrew's Square in Poveglia and held Bartolucci and his wife at gunpoint. The same time, troops seized control of all major radio and TV stations across Etruria. A staffer had informed General Ludovico Farnese in northern Etruria, which held predominately pro-Republic officers, of the coup. As Farnese prepared to consider ordering his troops airlifted to Poveglia to protect the president, he was removed by colonels within his command staff.

At 04.19am, the President of the Chamber of Representatives, Umberto Allegri, a member of the right-wing Patriotic League, telephoned the Palazzo Vittoria to inform President Bartolucci that the military action would be supported by the lower-house and that he was confident President Ettore Solariano would declare support for the action on behalf of the State Council (upper-house). Realising that he had no support in the Senate, the President acquiesced to the plotters, who presented him with a pre-written statement he would read out to a special joint-session of the Senate the following morning. Following his agreement, senior figures in the coup plot arrived in Poveglia, while the order for a joint-session was issued.

At 08.00am, President Bartolucci addressed the joint-session in which he read:

My esteemed friends, in the past few months, our country has descended into a period of great instability and internecine hatred and violence. Our current system of constitutionalism and governance is structurally inadequate to confront the crises engulfing our great country. As such, in acknowledgement of the fact that we cannot defend the peace nor the integrity of our federation and republic, I am formerly conceding government power to the military forces of our nation. I am in the understanding that they will strive to defeat the collectivist and separatist threat that endangers all peoples of Etruria, while maintaining the dignity and traditions of our democratic constitution. I urge the Senate of the United Etrurian Federation to agree and offer our military the support and trust needed to combat this dangerous enemy. May God bless us all and our military forces as they take upon the burden of governance and war, to maintain our great and strong nation.

Immediately upon his address finishing, armed soldiers entered the Hall of Saint Peter, which houses the joint-session. The President of the State Council, Ettore Solariano, then proceeded to demand a joint-session vote on accepting the letter by the military, which if passed would grant them extraordinary powers. Prior to his request, President Bartolucci read out a letter from his cabinet expressing their support for the military. It was later revealed that during the night, the military had stormed the homes of all cabinet ministers and forced their signatures at gunpoint. With the President's support and that of his cabinet, the Joint-Session voted unanimously in support of the letter, that would be called the Capitoline Accord. The vote, ultimately represented the fall and final demise of the Second Etrurian Republic.

Establishing the regime

Following the vote in the Joint-Session of the Etrurian Senate, the Supreme Command of the National Armed Forces moved swiftly to consolidate their control over the country. At 09.00am, General Sciarri took to national radio to proclaim a "government of national emergency and stabilisation" (Governo di Emergenza Nazionale e Stabilizzazione), in the same address he declared martial law across all of Etruria to confront "our enemies, domestic and foreign." The Army then deployed a further 35,000 soldiers to towns and cities across Etruria, while the Senate of Etruria was kept open and active, its corridors and halls were lined with armed soldiers at all times. On May 5, the Supreme Command declared the state administrations in Carinthia and Novalia void and arrested the state leaders and hundreds of political, social and civil service figures, while appointing military officers to head "Emergency Military Administrations" (Amministrazioni Militari di Emergenza).

Massimo Bartolucci resigned as President quietly and returned to his summer house on Lake Imperia, where he would remain until 1963, when he was disappeared by the military regime. His cabinet was kept intact by the Supreme Command who utilised them for implementing nominal social and economic policies. However, in June, the Ministers of National Defence, Internal Security, Justice and Foreign Affairs were sacked and replaced with military officers.

Yet throughout May, the major focus of the new regime was the mass deployment of military forces to the Western States and the decimation of the federal level, Party of Radical Workers - the country's premier Collectivist party. Between May 4 and May 10, over 3,500 PRW members were arrested by the military, including its leadership, a further 6,000 associated members and union representatives were detained from May until August, yet released. On May 25, the new regime amalgamated all federal law enforcement into the Organisation for National Vigilance and Security (OVNS), which was brought directly under the authority of the Supreme Command. The military directed OVNS to pursue and neutralise domestic opponents to the regime and separatists in the Western States, while slowly the Supreme Commander sidelined the Senate and cabinet from day-to-day governance.

On May 28, the Etrurian Army launched a full-scale offensive into the Western States, targeting known separatist hideouts, weapon and ammo dumps and training grounds. The mass deployment of troops to the west, effectively killed the 1946 Constitution. The operation resulted in the deaths of an estimated 200 people and the arrests of 600, the start of the offensive is generally accepted as the start of the Western Emergency.

On June 10, the Senate passed the military's Emergency Powers Act, that granted the Supreme Command the right to rule by decree. This was followed immediately with decrees formally banning all separatist parties, movements and clubs, as well as a decree greatly reducing the freedoms provided by the 1946 Constitution, with the introduction of censorship, closing down of regionalist media outlets and centralising of all federal media broadcasters. On June 25, the Supreme Command lifted the right of a fair trial and permitted detention without trial, which greatly aided in their ability to crush student opposition that was rapidly growing in Vespasia.

Throughout the remainder of 1960, the Supreme Command continued to launch mass arrests of leftists, critics, opponents of military rule and separatists across Etruria, while further marginalising the role and influence of the Senate over its actions and activities.

Sciarri period (1960-1974)

In the immediate after of the overthrow of Bartolucci, Francesco Augusto Sciarri, the head of the Supreme Command, became the de-facto head of government and state of Etruria. In this capacity, he led the way in consolidating further powers for the Supreme Command and marginalising the existing institutions. As such, throughout 1960, the regime focused on removing critics and opponents within Vespasia, while deploying military forces to the Western States.

In 1961, opposition to the military's rule began to organise itself among student bodies across Etruria, while the deployment of military forces to the west escalated the violence. In turn, Supreme Command under Sciarri stepped up repression of critics. Sciarri also sought to unify society against what the regime was describing as a "an attempted leftist revolution", in turn seeking to conflate the student protests with the separatist conflict in the west. This was aided by the nominal cooperation of several major national newspapers and TV outlets, who had come under the informal control of the Supreme Command.

In January, a major anti-war and anti-junta student protest was held simultaneously in Vicalvi and Stazzona, which involved an estimated 300,000 students and staff. In response, the military regime deployed soldiers and police, who acted without restraint and brutally repressed the marches. An estimated 800 were arrested, 400 injured and at least 36 killed either in the street or in police custody. The same day as the crackdown, the Supreme Command altered the rules of martial law, stating that any organised protest would result in immediate arrest and detention without trial and the withholding of state benefits to the families of those detained.

Consolidation of powers

Apocorona Incident

In wake of the crackdowns and further escalation of fighting in the west, the Supreme Command sought to rally and unify Etrurian society. Having seen some success in uniting Etruria by conflating student protests with the leftist uprising in the west as part of a wider "leftist plot backed by the MSU", the government turned to the disputed islands of Apokoronas held by Piraea following the Solarian War. The dispute was first raised in regime propaganda throughout 1960, as many in the Etrurian military believed the weak Piraese government was aiding or housing Carinthian and Novalian separatist leaders.

Preparations for a military operation to seize the disputed islands began shortly after the crackdowns on January 19. The Supreme Command opted to construct a media narrative that the islands were being used by Piraea to house, train and supply separatist groups across the west and within Tarpeia. Between February and April, the Supreme Command was regularly claiming it held evidence of training camps on the islands, while using forced confessions from separatists in Tarpeia to claim Piraese fishermen were smuggling guerillas and weapons into Tarpeia, to reach separatists in Carinthia and Novalia. On May 22, an explosion in Centurpie, the provincial capital of Tarpeia was blamed on separatists based on Vamos island, within the Apokoronas chain. Records released in 1995 proved that it was in fact a gas explosion, it was used successfully by Supreme Command to further present Piraea as a "safe haven for leftist terrorists and secessionists."

Efforts by the Piraese government to seek a diplomatic solution were regularly blocked by the Etrurian regime, which refused to negotiate with a "government backing those who would tear our country apart." While others in the regime questioned whether the Piraese government had even enough control over its own borders to offer solutions.

Owing to the short distance from Etruria, little time was needed to amass the necessary forces needed to secure control of the islands. Having 60,000 soldiers deployed across Carinthia, Novalia and Tarpeia further covered deployments from Piraese suspicion. Throughout June and July, the Supreme Command made regular statements indicating that it would use military force to "deny safe haven for all traitorous forces." This coincided with further Etrurian naval and air activity in and around the islands, while 5,500 marines were readied in Centuripe and Allagra.

On 5 August 1961, Etrurian marines backed by the Navy and Air Force launched an amphibious landing on five of the six inhabited islands. The islands, for the most part were only protected by armed police, while the largest island of Armenoi, had a garrison of 150 soldiers. The Etrurian Air Force bombed their garrison along with several police stations and the local airfield, killing 29 people. By the evening, the Etrurian military had seized complete control over four of the five islands. Armenoi would be fully seized by the early hours of August 6, after the Etrurian military captured the remaining Piraese soldiers who attempted to flee into the highlands to stage a guerilla action until Piraea could liberate the islands. The capture of the islands was announced by Francesco Sciarri on national radio, leading numerous celebrations across Vespasia and loyalist-held regions of Novalia. The Piraese government, refusing to go to war owing to Etruria's military superiority opted for diplomatic protests, which went unanswered by the international community.

On August 9, the islands were formally merged into the Federal Autonomous Territory of Tarpeia, this was followed by excessive human rights abuses against the local Piraese population. Over the next two decades the islands would undergo a limited form of Etrurianisation, a process used by the Etrurian Revolutionary Republic in occupied regions. This included the repression of non-Etrurian languages and culture and the import of Etrurian nationals. They remain in Etrurian hands and disputed by Piraea to this day. The success of the invasion greatly enhanced the regime's standing among the general population.