Military dictatorship in Etruria

This article is incomplete because it is pending further input from participants, or it is a work-in-progress by one author. Please comment on this article's talk page to share your input, comments and questions. Note: To contribute to this article, you may need to seek help from the author(s) of this page. |

United Etrurian Federation

3 other official names

| |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1960-1984 | |||||||||

Motto:

| |||||||||

Anthem:

| |||||||||

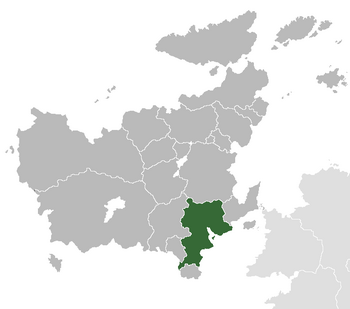

Etruria in green. | |||||||||

| Capital | Poveglia | ||||||||

| Government | Federal authoritarian military dictatorship | ||||||||

| Chief of State | |||||||||

• 1960-1974 | Francesco Augusto Sciarri | ||||||||

• 1974-1978 | Giovanni Aurelio Brocco | ||||||||

• 1978-1983 | Gennaro Aurelio Altieri | ||||||||

| Premier | |||||||||

• 1960-1974 | Guilio Cesare Tulliani | ||||||||

• 1974-1978 | Enrico Povegliano | ||||||||

• 1978-1983 | Alessandro Galtieri | ||||||||

| Legislature | Consultative Assembly | ||||||||

| History | |||||||||

| 14 May 1960 | |||||||||

| 1 July 1984 | |||||||||

| Population | |||||||||

• 1968 | 47,102,444 | ||||||||

• 1978 | 53,656,771 | ||||||||

• 1983 | 56,339,781 (estimate) | ||||||||

| Currency | Florin | ||||||||

| |||||||||

The Etrurian military government (Vespasian: Governo Militare Etruriano; Carinthian: Etrurijanska Vojaška Vlada; Novalian: Etrurijanska Vojna Vlada) was the authoritarian military dictatorship that ruled Etruria from 4 May, 1960 to 1 July, 1984. It began with the bloodless coup of President Massimo Bartolucci—and ended when Miloš Vidović took office on 1 July, 1984 as President. The military overthrow of Bartolucci was backed by the near entirety of the Etrurian officer corps and the Defence Staff of the Etrurian Armed Forces (Stato Maggiore della Difesa), who had lost faith in the democratic government to confront the Western Emergency, corruption and widely perceived social and moral decay.

Despite initial promises of the military government being temporary, the adoption of a Constitution of National Security the day following the initial coup, established a repressive military-dominated system that would govern Etruria for over 24 years. During its two-decade rule, the military government oversaw military operations against Carinthian and Novalian separatist groups, far-left guerillas and instigated two military operations against Piraea. Its technocratic approach to economic reform saw significant improvements to Etruria's national economy, which steadily recovered from the Solarian War and the poor economic management under the previous Etrurian Third Republic. Etruria's relations with its Euclean partners such as Werania, Estmere and Gaullica also saw dramatic improvement, while it became one of the leading anti-communist powers in Euclea. By the mid-1970s, the separatist and far-left insurgency in Carinthia and Novalia had been defeated, despite a period of high popular support, the removal of the security threat coupled with growing resentment over oppression led to a steady increase in support for the return of democracy. Beginning 1977, the military entered into negotiations with various democratic societies and groups. In 1984, the first general election since 1958 was held resulted in the return of civilian rule under Miloš Vidović and the Social Democratic Party.

Today, the military government is subject to debate and divided opinions. While many Etrurians recognise the military government's success in defeating the separatist threat and maintaining Etrurian national unity, as well as its successes with the economy, it is equally known for its repression, disappearances and gross human rights violations. Throughout it 24-years in power, the military government is believed to be responsible for the deaths of an estimated 18,000 people, who were killed in extra-judicial settings, the excessive use of capital punishment and torture or outright disappearances. A further 21,000 people died during the Western Emergency, of which, an estimated 7,600 were killed in government massacres. At least 3,205 still remaining missing from the period, while 111 mass graves have been discovered since 1984 that are attributed to the military government.

Background

Etruria's political crisis stemmed from the inadequacies of the new political system constructed in wake of the Solarian War, through the Community of Nations Mandate for Etruria. In an attempt to limit the influence of the security establishment and reinforce checks and balances, the Senate of Etruria was granted far-reaching powers and oversight over security policy. The failure of the post-war governments to equalise the pace of reconstruction across all states of the federation, allowed the festering and growth of separatist and far-leftist movements in Carinthia and Novalia. The post-war political system massively limited government responses to security crises, with deployments of police, the auxiliary gendarmes and regular military dependent upon votes in both houses of the Senate. This inability coincided with a wider sense of declinism across all Etruria, with the country gripped by post-war poverty, criminality and corruption. The social and moral decay perceived to be undermining Etrurian society, also led to a resurgence in support for right-wing and far-right parties and a general openness to authoritarian rule, if only to see the country’s course changed.

The emergence of secessionist movements in the western states first came about in the early 1950s, as these states saw significant inequalities in reconstruction and re-development compared to Vespasia. The use of proportional voting at the federal and state level, and the inability for the threshold to be increased from 3%, forced parties to enter complicated coalitions to form stable governments. The Democratic Worker’s Party had entered government in 1950 alongside the People’s Liberal Party and Sotirian Democracy, the former having ties to separatist parties in Carinthia and Novalia. The PLP was also one of the most forceful opponents of securitisation and militarisation in the federal legislature. Not only did this significantly reduce the federal government's ability to respond to the amassing of weapons by separatist militias, but further limited law enforcement's ability to investigate. The Democratic Action Party government (1948-1957), which drew many of its leading figures from the Community of Nations Mandate, refused to adopt harsh measures against separatist elements, go as far as to defend their rights under the constitution, alienating unionists in the centre-right and the military.

In 1952, the Novalian People’s Liberation Front was formed out of a grouping of Solarian War veterans. The NPLF attracted the attention of the socialist bloc in Euclea and was provided safe havens in Piraea and Amathia. The election of the centre-left Democratic Worker’s Party under President Ferdinando Grillo in 1953 did little to stem the growth of nationalism in Carinthia and Novalia. The same year, the various left-wing nationalist groups in Carinthia united to form the Combatant Front for Carinthian Liberation. In response, numerous pro-Etrurian nationalist movements rose up in response, including the Black Unionists and the National Volunteer Defence Front, by the end of the year both sides were clashing in running street battles across Carinthia and Novalia. In 1953, state elections in Novalia saw the Farmers and Workers Union led pro-Etrurian alliance win most seats in the state legislature, pushing the Novalian nationalists toward armed insurrection over democratic means of securing independence. That year, the NPLF attacked six police stations and army bases, distributing weapons and munitions to supporters. Similar actions took place in Carinthia, sparking the Western Emergency.

From 1953 until 1960, the nationalist armed groups would limit their attacks and operations, often just retaliating against unionist groups such as the NVDF. The violence further limited the degree of reconstruction and economic progress in both states, while the violence undermined the DWP government in Povelia. The violence, the wider sense of declinism among Etrurians, the stagnant economy and rampant corruption also provided a vital space for the resurgence of far-right politics at the national level. In the 1958 election, the New Republic Movement, a neo-functionalist party that advocated military action against the growing nationalist threat won over 35 seats. The inability by the central government to face the escalating violence in the west and the further refusal to call out foreign support drove many senior figures within the Etrurian armed forces to begin planning a seizure of power to protect national unity. On February 19 1959, the NPLF bombed the railroad connecting Vilanja to Drostar, causing a train to derail and leaving over 100 people dead. The next day, the Etrurian Armed Forces began to deploy forces without government permission, the subsequent political struggle saw the government acquiesce, empowering the generals who stepped up plans for a seizure of power.

Lead up to the 1960 coup

As the military began to deploy forces without federal authorisation in late 1959, tensions between the civilian government under President Bartolucci and the Defence Staff grew rapidly. Many in the government feared the military’s actions would escalate the so-far relatively low level violence in the west, while others saw the military’s intransigence as a threat to the republic. To the Defence Staff, they saw their actions as the only means to protect the country owing to the government’s weakness and inability to muster even a most basic response.

To reassert government control over the armed forces, the government prepared to secure a vote in the Senate ordering the redeployment of forces back to their garrisons. However, President Bartolucci found that he could not garner enough support from his own Democratic Action Party, let alone the necessary votes from Sotirian Democracy or the New Republic Movement, with the latter having opened talks with the Chiefs of the Defence Staff, affirming their intention to protect the armed forces. The vote held on January 18, failed with the government trounced 111-389. Many members of the Senate found the government’s actions perplexing to outright treasonous. The New Republic Movement for its part accused the government of acquiescence to “left-wing terrorists in the West.” While, the centre right Sotirian Democracy accused the DAP of overreacting to the military’s decision to defend the nation’s integrity.

In late January, President Bartolucci sought to sidestep the military by urging the Prefects of State in Carinthia and Novalia to declare the presence of federal forces in their states as unwanted and uninvited. It was hoped that such declarations would embarrass the armed forces into withdrawing their forces from the west of the country. On January 19, Novalian Prefect Petar Ogresta told newspaper journalists that he welcomed the presence of federal forces, “we are a state beset by left-wing enemies and the presence of federal forces is welcomed, for they now can know fear.” Ogresta’s response threw the government off-course, while many in the cabinet now questioned the political capabilities of President Bartolucci. Prefect of Carinthia, Zoran Potrč for his part questioned the suitability of federal armed forces policing his state’s streets but refused to publicly oppose their presence. Potrč would be assassinated by the CFLC in 1962.

Word of the government’s efforts confirmed to the Defence Staff that Bartolucci was more concerned about his image and weakness toward the left-wing groups in Carinthia and Novalia. On January 23, the Defence Staff met at the home of Major General Francesco Sciarri to discuss their next moves. Also present at the meeting was Giorgio Garafola, the leader of the far-right nationalist New Republic Movement, Garafola strongly advocated for a coup by the military, as he saw the insurgency in the west as inherently tied to the social decay afflicting the rest of the country. The influence the MNR had over the Defence Staff was considerable, many of the leading the commanders and officers had served during the Solarian War either as non-commissioned officers or recruits and were highly receptive to the nationalism of of the MNR. At this meeting, the Defence Staff with the support of Garafola agreed to pursue an overthrow of government.

Throughout February, the CFLC in Carinthia and the NPLF in Novalia stepped up their actions against state and federal forces, institutions and property. On February 18, the NPLF seized complete control over several villages on the border with Piraea, while the predominately Piraean-village of Stobea was captured by the NPLF with Piraean support in Etrurian Tarpeia. The capture of entire communities sent the government into a tailspin, while the events further confirmed the crisis situation among senior military officers.

In an effort to prepare the populace for a military takeover, Giorgio Garafola and the MNR stepped up their criticism of the Bartolucci government in the Senate. The government’s announcement that it would be willing to sit down in negotiation with the CFLC and NPLF infuriated much of the Etrurian right, with Sotirian Democracy withdrawing the Bartolucci government coalition, stripping its limited majority away. Its collapse was only averted by the offering of a confidence-and-supply motion by the pro-secessionist Carinthian Democratic Independence Party, which only further eroded what little faith the Right had in the government. On March 3, the Federal Minister for the Interior, Massimiliano Abate was shot dead by a member of the National Volunteer Defence Front for his weakness toward the left-wing groups. Abate’s relationship with the armed forces denied the government the last positive link it had to the officer corps.

From March until May, the Defence Staff actively planned for the overthrow of the government, going as far as create mock layouts of key government buildings and compounds in isolated areas of Vespasia for selected units to train seizing them. On May 10, President Bartolucci reaffirmed his government’s willingness to negotiate with secessionist groups on a radio broadcast to the nation. He said, “we can either pursue a peaceful solution to the worries and concerns of the Carinthian and Novalian peoples or we can pursue violence, cementing the division between our peoples.” A week before the coup itself, over 114 people were killed in pitched gun battle between the CFLC and local state forces in the capital Propoče. At least 33 civilians were killed in the crossfire, while the incident revealed the serious weaknesses in the state forces that were mostly relied upon. The Etrurian defence staff responded by ordering the deployment of 1,200 regulars to the city without federal authorisation.

According to documents published after 1984, the Bartolucci government received word of a possible coup on May 2 1960, with the report being dispatched by the pro-government Prefect of Dinara, who had in turn received word of unauthorised military training exercises near Castravona. However, the report was dismissed according to the documents, owing to President Bartolucci’s dismissal of the exercises as mere repeats of the army’s unauthorised deployments seen elsewhere. In the immediate days before the coup, the Defence Staff deployed elements of the 23rd Infantry Division (San Michele) and the 39th Infantry Brigade (Inferno) to training grounds in southern Veratia. These forces, numbering over 4,000 strong were only deployed a 40-minute drive from Povelia and spent the preceding days training in counter-insurgency operations, while the military invited the national media to document their activities. The right-wing newspapers in Etruria following the Solarian War had fallen under the control of two prominent families, who boasted significant personal ties to the military, often through high society. These families also lent their support to the NMR and Giorgio Garafola, who in turn used his relationships to secure the backing of the newspapers.

Coup d'état

In the late hours of 13 May 1960, the 23rd Infantry Division (San Michele) and 39th Infantry Brigade (Inferno) left their training groups and travelled south to Povelia, where they established blocking positions north, west and east of Tarceło, the mainland district of the capital. At 01.03am, the units crossed the Povelian causeway and entered the Palazzo Orsini, the official residence of the president. President Massimo Bartolucci was awoken by his personal domestic staff and as he entered his office, he was arrested by the soldiers. Vice President Vittore Uccello was detained at his personal home at Lido di Apostoli before being transported with President Bartolucci to a holding facility at San Marco Air Force Base. Simaltaneously, loyal cadets and officers from the National War Academy in Solaria, captured ARE's radio and television studios, while putchist elements in the various Vespasian state police forces arrested cabinet ministers at their personal residences. The President of the Chamber of Representatives, Mauro Dandolo had left the country on a personal vacation to Montecara, his deputy, Luigi Fabro was detained by putchist police officers. The Defence Staff had also dispatched small units to the residences of all 15 Prefects of State to ensure the cooperation of state-level administrations.

Radio address by Maj. Gen Francesco Augusto Sciarri

At approximately 6.30am, ARE broadcasted the radio message by Major General Francesco Augusto Sciarri confirming that the government had been overthrown. In his speech, he reassured the country of the military’s intentions, while also announcing the closing of the federal legislature, suspension of the constitution and the beginning of martial law. He called for national unity and promised the harsh measures announced would be temporary and that elections would be held within months to elect a new government. Several regional commanders who awoke to news of the coup promptly attempted to establish communications with central government, only to find themselves arrested by putchist officers. It was revealed in 1988, that the military had placed wiretaps on senior commanders deemed "unreliable" by the Defence Staff, however, the Defence Staff found that virtually the entirety of the commanding officer class of rank colonel upward were supportive of the coup. Following his radio address, Maj. Gen Sciarri and senior officers of the Defence Staff met with the heads of the state police forces and the Federal Criminal Investigative Service and secured their backing in the coup.

The right-wing newspapers owned by family businesses involved in the early planning of the coup and printed pro-coup headlines for the 14 May publications. The most widely read newspaper in Etruria at the time, the Telegrafo Nazionale printed the headline, "The military return as our saviours" and praised the military for its swift action to remove a government, "imprisoned by a foreign constitution, yet most cheerful in locking themselves inside", in reference to President Bartolucci's regular refusals to violate the constitution by ordering the deployment of federal forces without parliamentary approval. At 08.00am, Sciarri and other leading commanders entered the Palazzo San Pietro in Povelia, where they set up their headquarters in preparation for consolidating their control over Etruria.

Establishing the regime

Despite announcing the suspension of the Senate, the military ordered the return of all lawmakers to Povelia within 24-hours. Those inside the country who failed to attend faced the threat of arrest under charges of “undermining national security.” On May 15, a special joint-session was held, where Deputy President of the Chamber of the Representatives, Liugi Fabro presided. President of the Chamber, Mauro Dandolo who was in Montecara at the time of the coup, refused to return home and would live in exile there until his death in 1977. The military placed heavily armed soldiers throughout the chamber and only permitted pro-coup newspapers to attend the session in the press gallery. The declaration of martial law on the morning of May 14 resulted in the deployment of 40,000 soldiers to Etruria's largest cities over the next 48 hours.

The military, represented by General Augusto Galtieri (who sat in the Deputy President of the Chamber’s seat, just beneath the presiding Fabro) asked for members of both chambers of the Senate to officially recognise the coup as legitimate. At the time, Etruria’s legislature voted by voice with a rollcall of lawmakers. When the vote was called, the second name on the call, Stepan Augustinčić voted “nay” and was promptly dragged out of the chamber by two soldiers. Augustinčić would be imprisoned for three years before being placed under house arrest until his death in 1968. The final tally of votes in favour of legitimising the military coup was 559-1. Following the vote, Gen. Galtieri announced the adoption of a “National Security Constitution”, with Major General Sciarri adopting the title of Chief of State, which would replace the office of President as head of the Government of National Unity and Security. All state legislatures will be suspended, and the state governments will now be headed by two Co-Prefects, a civilian and a military officer, appointed by the GNUS. All law enforcement bodies will be centralised under the new government. Galtieri then dismissed the joint-session and ordered the Palazzo Repubblica locked, the Etrurian senate would not reopen its doors again for twenty-four years.

On May 16, Maj. Gen Sciarri assumed the office of Chief of State, appointing deputy leader of the New Republic Movement, Alessandro Scelba was Premier to assist in the governing of Etruria. NRM leader, Giorgio Garafola was appointed head of the Consultative Assembly, a rubber-stamp body charged with representing the interests and opinions of both the general populace and businesses. The GNUS was comprised of both civilians and military officers. Sciarri appointed fellow Defence Staff officers to the Ministries of the Interior, Defence, National Security, Culture and Information and Industry, while technocratic civilians were given the remaining posts.

All political parties and civil society groups were banned and shut down, with the notable exception of the New Republic Movement and Sotirian Democracy, who were tasked by the GNUS to “assist in the management and mobilisation of society against the left.” The centrist Democratic Action Party and the centre-left Democratic Worker’s Party were brutally shuttered, with their headquarters ransacked by the military and left in states of ruin. Far-left parties such as the Party of Radical Workers saw their leadership arrested and disappeared. The PRW’s leader, Paolo Moro was photographed being dragged out of the Senate, his body would be later discovered in a mass grave in 1999.

Almost immediately the military sought to consolidate its position with mass arrests and police actions against perceived “hostile political entities.” With the support of federal and state law enforcement, they arrested 15,000 people over the course of six days. Among those arrested were union members, journalists, federal, state and local level politicians, artists and playwrights. Hundreds of university lecturers and other academics were also detained, while several major universities noted to host vibrant and active left-wing align student unions were shut down. This included the two most prestigious universities in Etruria, the Metropolitan University of Solaria and the University of Tyrrenhus-Spataro. However, these two institutions would reopen within six months following the introduction of in-class room surveillance equipment and the replacement of left-wing academics with compliant lecturers.

On May 17, the GNUS announced a complete ban on all "non-registered" printed publications, the only publications to be permitted to print were the right-wing newspapers, Telegrafo Nazionale, Informatore Mattutino and numerous right-wing and loyal regional papers. The GNSU ordered the nationalisation of the entire Etrurian publishing industry, which resulted in the shutting of over 100 small to medium publishers in order to deny critics the opportunity to publish materials illicitly. Journalists who were not detained in the immediate days following the coup and previously wrote for liberal or left-wing publications, were subject to vigorous interrogations by military officers in order to secure renewed credentials. The GNUS would regularly revoke the credentials of journalists in order to silence criticism.

Documents released in 1998, showed that the military had developed extensive lists of “subversive elements” as early as 1955. Many of those detained within the first week of the junta were included on contigency plans produced by the Democratic Action government under Mauro Vittore Camillo. The DA plans included the names and addresses of various far-left individuals who were deemed likely to take part of a possible far-left take over of government. The same documents in 1998 revealed correspondence between Defence Staff officers where it was agreed that “a lightning strike against the radicals would be necessary.” This “lightning strike” would also serve to “send the populace into a state of frozen shock, weakening any opposition.” By the end of May, the position of the Government for National Unity and Security was secure, the rapid detention of thousands and the equally rapid establishment of the military government stunned the general populace into acquiesence, while considerable portions of the population had in fact welcomed the military takeover, even if there were concerns over the mass arrests and shut down of the media. On May 27, Sciarri made his first televised address after assuming power as Chief of State. In his address he vowed to “see Etruria through to the end in its war against socialism and its terror. We will be showing no quarter or mercy to those who would tear our nation apart. We will also see that Etruria be restored to its rightful place as one of the great powers of this continent. Our post-war humiliation ends here and now.”

Sciarri period (1960-1974)

With the regime’s position consolidated, Chief of State Sciarri began to make good on his promises made in his first radio broadcast following the 14 May coup. The first was to sign off on the sentencing of President Massimo Bartolucci and his government to life under house arrest. They were returned to their homes from the San Marco Air Force Base after a month in detention. He appointed General Giacomo Saragat as his successor as Chief of the Defence Staff and ordered the deployment of 40,000 soldiers to Carinthia and Novalia to “identify, locate and destroy” separatist groups.

On the 10 August 1960, the entire law enforcement aparatus of Etruria was fedederalised and amalgamated into the Organisation for Internal Vigilence and Security (Organizzazione per la Vigilanza e la Sicurezza Interna; OVISI). OVISI swiftly evolved into a considerable force in its own right, establishing an extensive network of informants across the entire the country not just the western states. With OVISI subordinate solely to the GNUS, it was able to operate without oversight or accountability, while, its direct line of communication to the military government permitted expedited deployment of resources, seen for example in the construction of several detention facilities, where torture, sexual and pyschological abuse became prevelant. According to documents released in the 1990s, OVISI boasted over 400,000 informants by 1980, though this has been debated by historians.

On the 1 November 1960, Sciarri and the GNUS issued “State Edict No.1” which suspended all criminal justice courts across the entire country. The same edict proclaimed all criminal cases will be tried at State Security Tribunals owing to the state of martial law. This edict served to remove from influence, any elements in the judiciary who may interfere or oppose the GNUS’ hardline against what it perceived to be “security threats”, though it also gave way to the excessive use of capital punishment for even the most lightest of charges. One notable example is that of 18-year old Mario Previti, who was sentenced to death for throwing a brick through the window of a police station in northern Veratia. The charges recorded officers mistaking the rock for a grenade, the correction was never made to the official charge sheet sent to the Security Tribunal and Previti was sentenced to death by hanging for throwing an “explosive device at state personnel.”

On 10 December 1960, the GNSU issued "State Edict No.2", mandating the merger of all trade unions under the umbrella National Association for Worker Interests (Associazione Nazionale per gli Interessi dei Lavoratori; ANIL). The GNSU had regularly attacked the trade union movement as being a "front for socialist radicals, tasked to infect Etrurian labourers and workers with alien ideals." In reality, ANIL proved highly ineffective in enforcing the military government's will on the industrial unions, where it suffered resistance throughout its 24-year reign. The treatment of unions also produced division within the GNUS, with several officers such as General Augusto Galtieri advocating for the complete abolition of trade unions, while more moderate figures like Gennaro Aurelio Altieri opposing such measures due to fears that it would provoke a general strike. The relationship between the trade unions and the GNSU through ANIL would often fluctuate between outright cooperation to intense confrontations. However, many historians note that the GNSU opted to avoid outright provocations of the union movement, instead utilising them as tools to win over working-class and urban poor support, especially in Vespasia. On the otherhand, many union leaders acquiesced to the GNSU's edicts and reforms through fear of personal arrest or being disappeared. The failure of the union movement to stand in solidarity with the numerous left-wing groups repressed or outright attacked by the regime would lead to the collapse in union activism following the restoration of democracy in 1984.

Escalation in the west

1961 protests

Technocratic reforms

Military operations against Piraea

In wake of the crackdowns and further escalation of fighting in the west, the Supreme Command sought to rally and unify Etrurian society. Having seen some success in uniting Etruria by conflating student protests with the leftist uprising in the west as part of a wider "leftist plot backed by the MSU", the government turned to the disputed islands of Apokoronas held by Piraea following the Solarian War. The dispute was first raised in regime propaganda throughout 1960, as many in the Etrurian military believed the weak Piraese government was aiding or housing Carinthian and Novalian separatist leaders.

Preparations for a military operation to seize the disputed islands began shortly after the crackdowns on January 19. The Supreme Command opted to construct a media narrative that the islands were being used by Piraea to house, train and supply separatist groups across the west and within Tarpeia. Between February and April, the Supreme Command was regularly claiming it held evidence of training camps on the islands, while using forced confessions from separatists in Tarpeia to claim Piraese fishermen were smuggling guerillas and weapons into Tarpeia, to reach separatists in Carinthia and Novalia. On May 22, an explosion in Centurpie, the provincial capital of Tarpeia was blamed on separatists based on Vamos island, within the Apokoronas chain. Records released in 1995 proved that it was in fact a gas explosion, it was used successfully by Supreme Command to further present Piraea as a "safe haven for leftist terrorists and secessionists."

Efforts by the Piraese government to seek a diplomatic solution were regularly blocked by the Etrurian regime, which refused to negotiate with a "government backing those who would tear our country apart." While others in the regime questioned whether the Piraese government had even enough control over its own borders to offer solutions.

Owing to the short distance from Etruria, little time was needed to amass the necessary forces needed to secure control of the islands. Having 60,000 soldiers deployed across Carinthia, Novalia and Tarpeia further covered deployments from Piraese suspicion. Throughout June and July, the Supreme Command made regular statements indicating that it would use military force to "deny safe haven for all traitorous forces." This coincided with further Etrurian naval and air activity in and around the islands, while 5,500 marines were readied in Centuripe and Allagra.

On 5 August 1961, Etrurian marines backed by the Navy and Air Force launched an amphibious landing on five of the six inhabited islands. The islands, for the most part were only protected by armed police, while the largest island of Armenoi, had a garrison of 150 soldiers. The Etrurian Air Force bombed their garrison along with several police stations and the local airfield, killing 29 people. By the evening, the Etrurian military had seized complete control over four of the five islands. Armenoi would be fully seized by the early hours of August 6, after the Etrurian military captured the remaining Piraese soldiers who attempted to flee into the highlands to stage a guerilla action until Piraea could liberate the islands. The capture of the islands was announced by Francesco Sciarri on national radio, leading numerous celebrations across Vespasia and loyalist-held regions of Novalia. The Piraese government, refusing to go to war owing to Etruria's military superiority opted for diplomatic protests, which went unanswered by the international community.

On August 9, the islands were formally merged into the Federal Autonomous Territory of Tarpeia, this was followed by excessive human rights abuses against the local Piraese population. Over the next two decades the islands would undergo a limited form of Etrurianisation, a process used by the Etrurian Revolutionary Republic in occupied regions. This included the repression of non-Etrurian languages and culture and the import of Etrurian nationals. They remain in Etrurian hands and disputed by Piraea to this day. The success of the invasion greatly enhanced the regime's standing among the general population.