Ziba: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 175: | Line 175: | ||

==Phonology== | ==Phonology== | ||

===Consonants=== | ===Consonants=== | ||

Ziba has twelve consonants, being not altogether dissimilar in size or selection to some of the {{wp|Austronesian languages|Vehemenic languages}} which Ziba is a neighbour to (such as | Ziba has twelve consonants, being not altogether dissimilar in size or selection to some of the {{wp|Austronesian languages|Vehemenic languages}} which Ziba is a neighbour to (such as [[Pelangi language|Pelangi]] or {{wp|Javanese language|Kabuese}}). There are, however, some cross-linguistically unusual features, namely: that all the consonants are voiced, or that there is no voicing distinction; that cross-linguistically common voiced consonants such as the {{wp|voiced alveolar lateral approximant}} ([{{IPA link|l}}]) or the voiced labial–velar approximant ([{{IPA link|w}}]), and that there is a distinction between a {{wp|sibilant consonant|sibilant}} and non-sibilant {{wp|fricative}}. | ||

The "regular" articulatory distribution of Ziba consonants may be regarded as a form of systematic phonemic differentiation, though it may also have been influenced by intentional prescriptive language reform in the Aguda Empire. The collapsing of voicing may also be a relatively recent and related feature. | The "regular" articulatory distribution of Ziba consonants may be regarded as a form of systematic phonemic differentiation, though it may also have been influenced by intentional prescriptive language reform in the Aguda Empire. The collapsing of voicing may also be a relatively recent and related feature. | ||

Revision as of 08:50, 20 September 2022

| Ziba | |

|---|---|

ziba | |

| Pronunciation | IPA: [ziba] |

| Region | Northern Southeast Coius |

| Ethnicity | Dezevauni people, Dhavoni people, Gowsas |

Native speakers | ~200,000,000 (2020) |

Standard forms | Harmonised Ziba (Dezevau)

|

| Dialects |

|

| Ziba script | |

| Official status | |

Official language in | |

Recognised minority language in | |

| Regulated by | Ziba Harmonisation Agency (Dezevau) |

| Language codes | |

| ISO 639-3 | – |

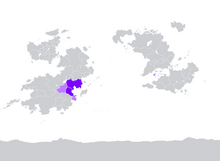

Countries where Ziba is an official or national language Countries where Ziba is a recognised or regional language but not an official or national language | |

Ziba is the only extant language of the eponymous Zibaic language family. It originated in and is the main language in Dezevau and northern Lavana, and also has legal recognition in Hacyinia and Carucere. It is spoken natively by over 200 million people, making it the fifth language in the world by native speakers, and a further xxx million speak it non-natively.

Ziba originated in southwest Dezevau several millennia ago, possibly as a contact language. It spread by trade and diplomacy among the region's city-states and other polities, as well as through migration, and association with Badi. In the medieval period, in large areas of northern Southeast Coius, Ziba was used in public, commercial, political, religious and diplomatic life, but coexisted with a variety of languages which were natively spoken at home, in circumstances of diglossia. At least in southwest Dezevau and among some classes, however, it was also a domestic language.

The Aguda Empire, founded in 1476, established Ziba as the official language throughout its territories, using it in administration, spreading it through commerce, deepening its Badist association, and generally promoting it as part of its assimilative policies. The state of diglossia collapsed across much of the Aguda Empire's territory, in favour of Ziba monolingualism. Ziba acquired more ethnic-political implication as a result of the empire's policies. The Aguda Empire also conducted early efforts at language reform and standardisation, with the Ziba dialect continuum converging considerably, and the koiné Agudan Ziba becoming the basis for virtually all later prestige dialects of Ziba. During the colonial and post-colonial periods, Ziba lost much of its status and reach outside of present-day Dezevau and Lavana, as colonial or other national languages were promoted instead. It remains an important world language, with many of its neighbours retaining loanwords from it, and it being the working language of the Brown Sea Community.

Ziba is an agglutinative language, with a great deal of suffixation to create new nouns and adjectives, sharing similarities in this with the neighbouring Vehemenic languages. Verbs, in comparison, exist simply within a SVO or SOV sentence structure. Ziba's possible roots as a contact language, and its storied use as a second language in the public sphere may be linked to its simple grammar and small phonemic inventory; it has twelve consonants and five vowels (which can form further diphthongs). Its inventory is unusual, however, in not having any rounded vowels, unvoiced consonants/voicing distinction, and a number of other features which are very cross-linguistically common. Virtually all Ziba is written in the Ziba script, which is somewhere between an alphabet and an abugida; it has had a very close phonetic correspondence since the orthographic reforms of the Aguda Empire.

History

Old Ziba

Old Ziba is the oldest attested form of Ziba, with conjectural reconstructions of its ancestor being referred to as Proto-Zibaic. Writing in Old Ziba script has mostly been discovered in southwestern Dezevau, in the lower Zigiava and Buiganhingi river basins, in areas associated with the Dhebinhejo Culture; it is possible it was spoken more widely. The oldest surviving inscriptions are generally carvings on inorganic materials such as stone, dating to between around 1000 BCE and 1 BCE. Surviving attestations are sparse and fragmentary; it is likely that most writing occurred on organic materials, which decayed in the warm and humid conditions of the region.

Though there is still much unknown about Old Ziba, it was very different to later forms of Ziba. It was an inflectional language, with the Old Ziba script using an assortment of pictograms and an abugida for content words, and only the abugida for function words; the abugida elements developed into Ziba script, with pictograms largely being lost in the transition to Middle Ziba. It is unclear whether Old Ziba had a larger or smaller phonemic inventory than modern Ziba, as it is unclear whether the use of different letters was regional or stylistic variation, or actually representative of phonemic distinction. In some cases, the Old Ziba script was also used to write other Zibaic languages, though these went extinct by the first millennium CE. Though Old Ziba is not at all mutually intelligible with modern Ziba, a considerable amount of modern Ziba vocabulary can be traced directly to Old Ziba.

Old Ziba was used for a variety of purposes, including commercial recordkeeping, religion, letter sending, and perhaps even decoration or signage. As in virtually all ancient societies, literacy was limited to a minority of powerful, wealthy or educated people, so given the dearth of surviving material, its everyday usage is difficult to attest to. With the language spreading to or taking root in the lower Bugunho basin, the Zedenge valley and other areas, it was particularly its association with Badi and its use for trade that became prominent. As the language transitioned into being the high variety in a widespread diglossia, and as it acquired many of the features common to contact languages (such as more analytical grammar and simplification of irregularities), linguists mark the end of Old Ziba and the beginning of Middle Ziba around 500 to 750 CE.

Middle Ziba

Middle Ziba, as the common language of the increasingly wealthy and populous Dezevauni city-states, spread through its use in trade and diplomacy, as well as (to a lesser extent) through its customary usage in Badi. A large diglossic area was established across northern Southeast Coius, with Middle Ziba as the high variety, and a variety of local languages (including Kachai, Ywe and Kabuese) as low. In a few areas, often communities where slaves, merchants or commingled refugees or economic migrants settled, it took over as the sole language.

The spread of Middle Ziba was associated with great linguistic change. In terms of grammar, it moved away from inflection towards analysis and agglutination, lost syntactic irregularities associated with particular words, and converged the morphology of different word classes (nouns, adjectives and verbs). It also experienced a variety of sound changes, often diverging in different dialects, to the extent that a continuum may have been formed. Lexically, it acquired many loanwords, both from other trade languages and from the low varieties in the diglossias it was part of. Pictographic elements in script fell entirely out of regular usage, and the Middle Ziba script was generally simpler and more stylistically regular than the Old Ziba one. This may have borne relation to generally higher levels of literacy in the region at the time.

Middle Ziba's status ebbed and flowed with the Dezevauni city-states, whose relative stability for some centuries saw also a relatively stable and slowly growing diglossia exist over much of eastern Coius for several centuries. The relationship between Badi and Ziba declined in importance over time, as Badist communities normalised the use of other languages, even as Middle Ziba got steadily further away from the Old Ziba which was first associated with Badi. The relationship would be strengthened by the advent of the Aguda Empire, however, whose strong religious character was combined with programs of linguistic, cultural, ethnic, economic, etc. assimilation.

Aguda Empire

Early Aguda Empire

The Aguda Empire, as established in 1476, came from the Ziba-speaking world. Initially, its court used the dialect used in Gobobudi, from whence its founders had come, but as it expanded, its programmes brought speakers of different dialects and different (diglossic) low languages together. A distinctive Agudan Ziba emerged first as a koiné used in the imperial court, becoming more widespread with the growth of Dabadonga, the new capital city.

The Aguda Empire used Ziba as its language of administration, and through its encouragement of commerce, also spurred the use of Ziba that way. The centrality of Badi to its ideological programme meant that it engaged with populations in local languages for proselytic purposes, but Ziba was the main Badist language, in terms of scripture, discourse, and so on. Organically, Agudan Ziba's role as a koiné grew, and it became the norm throughout the governing class.

As the Aguda Empire became more established, and as economic and cultural integration accelerated, diglossia collapsed in favour of Ziba monolingualism in the empire's core regions. Though a slow process, it was noted with approval by the imperial government, though it was not seen as something that it was sensible to interfere with as a matter of policy, inasmuch as it would be more trouble than it was worth to monitor what language people used in their own homes.

Aguda Reforms

Duazaiginhe, elected in 1563 as the fifth zeja (emperor) of the Aguda Empire, initiated and promulgated a number of linguistic policies and reforms; Agudan Ziba most often refers to the form of the language that existed from their reign until the end of the empire and the advent of the colonial period. Duazaiginhe wrote that their motivation for language reform was twofold. Firstly, there was a need for a unified, formal, standard language, to promote cultural unity and to prevent legal ambiguity across the empire (though they did not envision that adoption needed to be compulsory or complete outside of the legal system). Secondly, they saw many of the features of Middle Ziba (or at least some dialects thereof) to be confusing, unnecessarily complex or antiquated, wasting time and resources.

Similar views were held by previous zejas and others in government, but wars and other matters had occupied governmental attentions for much of the time prior to Duazaiginhe's ascension. They commissioned a council of scholars to draft reforms and standing policies, with the council doing most of the work, though they also had personal involvement in the process. The reforms came out in three main waves, some years apart, the last mainly being promulgated by Duazaiginhe's successor. Their effects were wide-ranging, though some features fell quickly out of usage, and on Duazaiginhe's insistence, were often retracted where this occurred, as so to preserve legitimacy and integrity. Historically, linguistic reform is rarely adopted in vernacular usage, especially in the premodern era, so the fact that even a few basic features of these reforms survived makes them unusually successful. Features included the authoritative definition of the script (which survives to this day), the preferencing of particular words (over other synonyms, especially loanwords) and official pronunciation guides, including permissible dialectal variations. Materials from the reign of Duazaiginhe have been invaluable for the historical linguistic study of Ziba, though the practice of rescinding unsuccessful elements of the reforms has made it difficult to establish what was official at any one time or not.

On the whole, the reforms heralded a more interventionist and assimilative attitude by the Aguda government on language policy, though the Badist religion always remained its ideological mainstay.

Colonisation

Colonisation of the Ziba-speaking world, primarily by Estmere and Gaullica, resulted in a decline in the language's prestige and usefulness, as the Aguda Empire's territories and sphere of influence were taken and carved up. In particular, the reorientation of trade to the seas and the creation of borders which barred trade were detrimental. In the remaining areas where diglossia still existed, it began to collapse in favour of the lower language, rather than Ziba, or it was that a colonial language replaced Ziba as the high language.

However, Ziba did remain in use, and was even preferred by colonial authorities at times, as an easily accessible and established language of administration. It also continued to be used as the native language in areas where it was established as such.

The dissolution of the Aguda Empire also saw increased divergence in the dialects of Ziba, some of which approached mutual unintelligibility, or which even were replaced by contact languages in marginal regions. Notably, trade pidgins on Lake Zindarud crystallised into Dazeda, a Ziba-based creole.

The phenomenon of gowsas (indentured labour being sent to Euclean colonies in the Asterias and elsewhere), meanwhile, saw the emergence of Asterian Ziba dialects, including notably Carucerean Ziba. Gowsas, drawn from across the Aguda Empire's territories or ex-territories, often found that Ziba was the only language they shared, and levelled to it even if it was not their native language, replicating a similar dynamic to that of the koiné Agudan Ziba.

Over time, many loanwords entered Ziba from colonial languages, principally Estmerish and Gaullican, but also from Solarian, as classicisms, and also some other languages such as Soravian, Weranian and Amathian. Many of these words were to do with the new ideas and things introduced by Euclean colonialism, ranging from political ideologies to industrial equipment to Solarian law concepts to Euclean culture.

The late colonial period, as a result of the advent of newspapers, telegraphs, railways, printing presses, public schools, industrial urbanisation and so on, saw a proliferation in the amount and availability of written material. Some nascent political movements, including socialist, nationalist and pro-independence, promoted the use of Ziba at this time, contributing to a renaissance. These developments were repressed to an extent by colonial authorities, particularly the national functionalist Gaullican regime through the Bureau for Southeast Coius.

Modern

computerisation

Harmonisation

Geographic distribution

Official status

Dialects

Phonology

Consonants

Ziba has twelve consonants, being not altogether dissimilar in size or selection to some of the Vehemenic languages which Ziba is a neighbour to (such as Pelangi or Kabuese). There are, however, some cross-linguistically unusual features, namely: that all the consonants are voiced, or that there is no voicing distinction; that cross-linguistically common voiced consonants such as the voiced alveolar lateral approximant ([l]) or the voiced labial–velar approximant ([w]), and that there is a distinction between a sibilant and non-sibilant fricative.

The "regular" articulatory distribution of Ziba consonants may be regarded as a form of systematic phonemic differentiation, though it may also have been influenced by intentional prescriptive language reform in the Aguda Empire. The collapsing of voicing may also be a relatively recent and related feature.

| Bilabial | Labiodental | Alveolar | Palatal | Velar | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Nasal | m | ɱ | n | ɲ | ŋ | |

| Stop | b | b̪ | d | ɟ | g | |

| Fricative | sibilant | z | ||||

| non-sibilant | ð̠ | |||||

Vowels

For monophthongs, Ziba has a fairly straightforward five vowel system. Notably, however, it lacks rounded vowels in most dialects.

Ziba has diphthongs, which occupy the same phonotactic position as monophthongs. A diphthong can be formed from any two monophthongs other than the mid central vowel (ə). This formula means there are twelve possible diphthongs.

| Front | Central | Back | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Close | i | ɯ | |

| Mid | ə | ||

| Open | a | ɒ |

Phonotactics

Ziba prescribes a syllable structure of CV. This somewhat unusual strictness can be a cause of difficulty when transcribing into Ziba from other languages.

The abugida or abugida-like and cursive Ziba script corresponds to the phonotactics, inasmuch as there is no usual way to write consonant clusters, consonantless vowels or triphthongs.