Son of Man: Difference between revisions

No edit summary |

|||

| Line 108: | Line 108: | ||

[[Category:Culture of Dezevau]] | [[Category:Culture of Dezevau]] | ||

[[Category:Films]] | [[Category:Films]] | ||

[[Category:LGBT (Kylaris)]] | |||

[[Category:Montecara Film Festival]] | [[Category:Montecara Film Festival]] | ||

Latest revision as of 15:08, 20 April 2023

| Son of Man | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fils de l'Homme | |

| Directed by | Zono Zuagai and Mouzou Bemejai |

| Written by | Zono Zuagai |

| Based on | Passion of Jesus |

| Produced by | Jiba Zugaumo and Buaje Buaje |

| Starring | Azad Hosseini, Didhuove Zeminhou and Nadia Panjang |

| Cinematography | Dejia Gaubina |

| Edited by | Dejia Gaubina |

| Music by | Sally Mhudhu |

Release dates |

|

Running time | 102 minutes |

| Country | Dezevau |

| Language | Gaullican |

Son of Man (Gaullican: Fils de l'Homme) is a 2022 Gaullican-language film, loosely based on the Passion of Jesus but set in a modern city, and without the presence of any divinity in the story. It was directed jointly by Zono Zuagai and Mouzou Bemejai, who also worked on the film in other capacities. Cinematography and editing were overseen by Dejina Gaubina, who was considered the third creative force behind the film. Azad Hosseini, Didhuove Zeminhou and Nadia Panjang starred as Jesus, Judas Iscariot and Mary respectively; there was some praise for the culturally diverse casting. The film runs for 102 minutes, and was produced in Dezevau, under the auspices of the Dezevauni Film Agency, a Dezevauni government body.

The film's creative conception was in 2021, according to Zono Zuagai, and was put to and received support from the Dezevauni Film Agency that same year. The bulk of filming took place in 2022, with the premiere occurring at the 83rd Montecara Film Festival in October of that year. On the whole, the production of the film was quite speedy, with Zono saying that it was as though the concept formed and spilled out of his mind fully-formed. Early concerns from the Dezevauni Film Agency about potentially controversial topics and themes were resolved early on in production, but came back to the fore when it was being considered whether to submit the film to the Montecara Film Festival; it eventually was, after some preliminary canvassing and reassurances from the filmmakers. It was also shown in cinemas in Dezevau starting October 2022.

Classification and interpretation of the film have been contested and fraught. It has been considered art film, psychological drama, absurdist, postmodernist or even speculative historical or historical fantasy. At points, it borders on the surreal, dark comedy, or satire. A term used by some critics which was acknowledged by Zono was "demythologisation". Some have said that it has some of the characteristics of naive art, noting the inexperience of the makers and novelty of their ideas, though others say that it fits within Dezevauni film as a whole, whose conventions are only relatively unknown worldwide. Critical reception has generally been positive, focusing on its atmosphere, themes and cinematographic techniques, with most criticism being of the plot, including on the basis of insensitivity or tastelessness. In some places, it was censored.

Plot

The film starts with a soft-spoken and slightly awkward man, Jesus, receiving various friends, who, unannounced, have shown up at his new apartment to congratulate him on his new job and on moving in. He receives them as best he can, but fairly simply, as he seems somewhat familiar to modern kitchen appliances. Two of the unnamed friends present Jesus with a palm frond-patterned doormat together. Jesus' mother, Mary, arrives after the friends have been there for a short time, and in an aside from Jesus' friends chatting in the living room, Mary expresses the greatest affection and pride for her son, and expresses regret that Joseph was unable to come visit at this time (Joseph, it is revealed, was Jesus' stepfather, and a good parent compared to his absentee biological father). Hugging his mother, Jesus tears up, his polite smile replaced by a tight-lipped frown, in arguably the most recognisable still of the film.

In the next scene (at least a day later, considering the time of day and changes of clothes) Judas rings the doorbell to take Jesus to his appointment at the bank (or government office), which he has apparently forgotten he had. They walk through the city on an overcast afternoon, talking amicably on various topics, some bordering on the political. Jesus challenges Judas as to whether his line of work is ethical (it is unspecified but implied that Judas is some kind of manager, bureaucrat or lawyer), but Jesus has no answer for Judas' response that he can never be completely sure, but can only try his best.

At the bank, Jesus is fidgety while waiting his turn, but Judas reassures him, and starts reading a newspaper. Jesus notices and approaches an old woman who is crying as she leaves her own appointment. Comforting her, he cannot understand the complex financial problem she seems to be having, though its crux seems to be that she will lose her house because of a third-party fraud. He approaches a banker or bureaucrat who is between clients and tries to get it resolved, to little success, becoming increasingly agitated in the process. Quickly, he has the attention of the whole lobby, and he starts shouting about the unfairness of the system and accusing the bankers of perpetuating it. In the process, he knocks some sheaves of paper, a vase and some other objects to the ground. Though he earns some sympathetic looks, he departs amidst silence once his rant has come to a head, Judas leading him away.

Back in his apartment, Jesus and Judas are sitting in silence when there is a knock on the door. The police inform him that charges will not be pressed, but issue a formal warning, and advise him to find a different branch for his banking services from now on. Despite this, they are sympathetic, in part because of Judas' intercession and promise to take care of him, and in part because they are mistaken that Jesus' outburst at the bank was because he was under financial stress himself. The police leave Jesus with some generic advice, and contacts for mental health support. Jesus, who since leaving the bank has been withdrawn and hesitant, seizes Judas, and forcefully pleads with him to promise not to tell any of their other friends that any of this occurred. Reluctantly, Judas promises.

In the next scene, Jesus, Judas and eleven friends are eating dinner in a private dining room at a restaurant. The alcohol is flowing, and everyone seems to be enjoying themselves. Jesus, somewhat intoxicated, starts making strange jests, such as saying that certain drinks and food are his blood and flesh; his friends laugh it off. His mood becomes stranger, however, and he starts accusing his friends, saying that they will betray him soon. Though nobody is quite sure if he is serious, they each earnestly deny the charges, and Jesus settles back down, the awkward situation defused. The meal is soon finished, and the friends sit around, drinking or smoking (presumably tobacco or cannabis). Jesus steps outside for a moment to get some fresh air, but asks them not to fall asleep while he is out. Silent and still, he stares at the brightly lit night cityscape for a long time (some uninterrupted minutes of the film), then steps back inside.

He finds three of his friends have dozed off, and he shakes his head and sighs, but sits back down to continue drinking and smoking. He becomes very still after a little while, then alternately shaky in his movements, and his gaze goes blank; Judas sits down next to him, first suggesting he finish on alcohol for the night, and then holding him by the arm or hand and soothing him. Judas takes Jesus' head in his arms and kisses him once or twice on the forehead or temple. The other friends have noticed by now, and when they ask if Jesus is okay, Judas mentions that he has not been well recently. Jesus seems to come to his senses, stands up quickly and angrily says that Judas has betrayed him. He accuses them all, but mainly Judas, of not taking him seriously, of being unable to see him as human. When his friends begin to murmur apologies for if they have been insensitive and encourage him to talk to them, and say that they are there to support him, he starts to sob, choking out what might be a word of apology, and turns and runs from the room. Judas stands up to give chase after a few moments, leaving the other confused friends behind, and calling Mary on his cellphone as he does.

Jesus hastily unlocks a drawer in his apartment to retrieve a revolver, apparently already loaded. He rushes outside to the alley outside his apartment, and stands there, looking at the gun, and then at the city and the night sky. He points the gun upwards from under his chin, finger on the trigger, but cannot bring himself to do it. He lowers the gun, then raises it again, then lowers it again, when a pedestrian sees him and gasps, thinking he means harm. He accidentally drops the gun, and it fires when it strikes the ground; the pedestrian is unhurt, but runs off shouting for help. Shocked, he walks towards the entrance of the alley; police arrive by foot from nearby, including the policemen who checked on him in his apartment after the incident at the bank. He is recognised as "that psych case"; the police yell various things at him, including instructions to put his hands up, which he does not follow; he stands still, not facing them. When he is asked by loudspeaker if he is a danger to himself or others, he turns angrily towards the police and yells, "so what if I am?" In reaction to his sudden movement, he is instantly shot multiple times by the police, and he falls to the ground, arms outstretched, as if in the shape of a cross.

Mary sprints past the police, who still have their guns up, wailing, sees Jesus, and throws herself onto him. He looks at her blankly for some seconds, then closes his eyes, dead. She holds his body, in a manner resembling Vadera's Pietà, for some seconds, before the police are heard to rush in, and the camera pans slowly upwards, past the rooftops, over the extensive skyline of the city, onto the earliest visible light of dawn on the horizon, and then there is a fade to black as the film ends.

Cast

- Azad Hosseini as Jesus

- Didhuove Zeminhou as Judas Iscariot

- Nadia Panjang as Mary, mother of Jesus

- ... as the Twelve Apostles (other than Judas)/friends

- Vouziga Manediu and Mivedai Zuagai as the two policemen

- Moagameme Dhijivodhi as the old woman at the bank

- Marina Tuah as the banker/bureaucrat

- Zono Zuagai as Joseph (non-acting role)

Azad Hosseini is Kexri, and Nadia Panjang is Pelangi, filling two of the three main character roles; the film was praised for contributing to the visibility of Dezevau's minorities, and helping them break into top-tier positions in film. Casting was done by open call, except for Azad Hosseini, who was a personal friend of Mouzou Bemejai.

Production

On the whole, production was quite speedy, with Zono saying that it was as if the film spilled from his mind fully-formed, but also praising the efficiency of all involved. All in all, several dozen people were involved in some way, at one point or another, with production; relatively few for a prominent feature-length film.

Development

Zono Zuagai and Mouzou Bemejai, close friends since university, wrote the bulk of the script over a few consecutive nights in 2021, presenting it to the Dezevauni Film Agency completed. In interviews, they have cited influences as disparate as the Bible, Cat on a Hot Tin Roof, the Pietà of Tiziano della Vadera, Mother with her Dead Son (another Pietà), Joker, La Vie de Brian and Giàn il sìmplio (the 1950 Béco aùreo winner).

Jiba Zugaumo and Buaje Buaje from the Dezevauni Film Agency were made producers, though they were fairly hands-off, given the limited scope and productional complexity of the film.

Azad Hosseini was a friend of Mouzou's with little acting experience, but persuaded to take part and trained for the role over two years. Casting of the other roles was by more conventional call.

Filming

Filming was done almost completely in a couple of locations in Bagabiada, with there only being a few different indoor scenes. Aerial footage of the city was captured using a remote-controlled drone; some short clips of footage from other places were used, generally as filler or transitions. Outdoor filming was helped by the fact that most outdoor scenes took place at night, when there were few people around or issues with using public space. The Bagabiada city authorities were generally helpful with logistics and legalities. The look of light reflecting on wet ground at night was also an important aesthetic consideration, also helped by the frequent rain of the Dezevauni climate.

Dejia Gaubina did both the editing and the cinematography, a task of some magnitude, but enabling a greater degree of unity between the two processes.

The decision was made to do the film in 1.375:1 aspect ratio early on, both because of its common usage in Dezevau, but also because of the "confined", "traditional" or "direct" feel it gave.

Music

Sally Mhudhu not only composed and helped record the music for the film, but was also involved to an extent in sound design. Though classically trained, she was hired for the prominence of her electropop work. She was one of the youngest heads of music, if not the youngest, to work on a Dezevauni Film Agency feature film. Some of her pieces written for the film have attained popularity in their own right, with her stature as an independent musician boosted by the film.

Subtitles

Versions of the film with official subtitles in Ziba and Estmerish (the film being in Gaullican) were prepared for release. Subtle differences exist in the Ziba subtitling, with some references to capitalist society (such as some of the financial terms) being replaced by terms which would be more familiar in a socialist context; this is mainly relevant in the bank scene, where the bank is intended to represent any kind of alienating, distant, impersonal authority.

Release

The film was nominated by the Dezevauni Film Agency to represent the country at the 83rd Montecara Film Festival, after several years of non-participation because of a lack of interest, resources or quality films. Partially because of this, the film drew sizeable crowds on release in Dezevau in cinemas (shortly after its premiere at the Montecara Film Festival. It was rated as unsuitable for young children because of themes of violence, death and mental illness.

The decision to nominate the film for the Montecara Film Festival was only made quite late, as there were concerns that the film's content could be too provocative for the international stage. Zono Zuagai and others involved in the film's production did their best to convince the Dezevauni Film Agency, seeing it as not only an opportunity to promote their own work but to demonstrate the maturity of the Dezevauni filmmaking scene. Zono recounts that one of the breaking points was when he pointed out the controversial themes of past Béco aùreo winners, such as Kaze no Hai (a 1994 film about the Senrian Genocide).

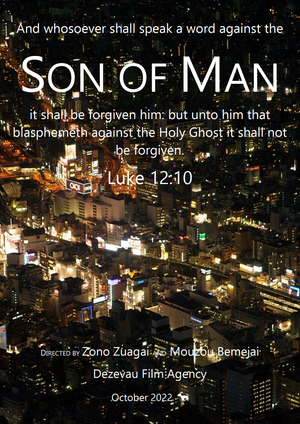

Conventional movie posters are not usually drawn up for films in Dezevau, and thus one had to be assembled at quick notice when the nomination was made (with versions in Estmerish, Gaullican and Ziba).

Further information on its performance at release is not yet available, nor has the winner of the Montecara Film Festival been announced yet.

Censorship

Son of Man, because of its depiction of Jesus as mentally ill, queer and not divine, was censored in some places or by some bodies. In Rwizikuru, the Royal Rwizikuran Film Board banned it from being screened in cinemas or sold because of "blasphemy".

Reception

The film received generally positive reviews from film critics in Dezevau and internationally. It was praised for its atmosphere, novel cinematography, casting, novel plot, themes, music, emotional sincerity and overall cohesion, while criticism mostly focused on the actual meaning of the plot, dialogue, insensitivity as to culture, religion or mental health, and some technical issues. Some said it had characteristics of naive art, though others disagreed, saying that this assessment was a result of unfamiliarity with Dezevauni film. The film was somewhat divisive in terms of its critical reception.

There are a variety of competing interpretations as to the film's central thrust. These include the demythologisation or desecration of the Sotirian idea, its reinterpretation to be relevant as allegory in a post-"God is dead" world, moral nihilism, understanding and support for mental illness, modernist or capitalist anomie or alienation, or just experimentally "straight", "blank" character study. By disempowering Jesus' death, the film may be taken to be directly contending that death is not meaningful, and mental illness not to be mysticised and romanticised; its broader allegorical comment on Sotirianity is generally more controversial. There is considerable contestation about whether the film ultimately opposes Sotirianity.

The queer implications between Jesus and Judas Iscariot, the reinterpretation of Judas as a benevolent character and the denigration of Jesus' character have all been the subject of controversy, aside from the film's overall philosophical contention. The Episemialist Patriarch of Noavanau called the film "theologically problematic".

In terms of genre, the film has been called art film, psychological drama, absurdist, postmodernist or even speculative historical or historical fantasy, surreal, dark comedy, or satire. One critic referred to it as a "modern drama of manners".

While the film has been called a breakout film for the Dezevauni filmmaking scene, others have countered such claims with the fact that the film is in Gaullican, about Sotirianity, set in a society which is not necessarily recognisably Dezevauni. Praise has been more consistent about its casting of ethnic minorities of Dezevau, however, who have traditionally found it difficult to be cast in lead roles.