User:Tranvea/Sandbox Misc: Difference between revisions

| Line 36: | Line 36: | ||

The campaign began to drawdown by 1985 and was officially dissolved in 1988 by order of the [[Central Command Council]], which proclaimed the [[Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics]], "unified, stabilised and introduced to social harmony." While the campaign delivered rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and modern technologies, it also significantly disrupted the lives of millions, who were evicted and transported away from their communities or places of birth. The attacks on cultural uniqueness of the various minorities has led many to accuse the campaign to have engaged in {{wp|cultural genocide}}, while the cost in lives from both direct violence and indirectly through resettlement has led others to describe a viable case of {{wp|ethnic cleansing}} and {{wp|genocide}}. The replacement of resetteled minorities by Pardarians and Rahelians also draws much continued condemnation. Today, it is a criminal offence in Zorasan to refer to the campaign as a {{wp|crime against humanity}}. | The campaign began to drawdown by 1985 and was officially dissolved in 1988 by order of the [[Central Command Council]], which proclaimed the [[Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics]], "unified, stabilised and introduced to social harmony." While the campaign delivered rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and modern technologies, it also significantly disrupted the lives of millions, who were evicted and transported away from their communities or places of birth. The attacks on cultural uniqueness of the various minorities has led many to accuse the campaign to have engaged in {{wp|cultural genocide}}, while the cost in lives from both direct violence and indirectly through resettlement has led others to describe a viable case of {{wp|ethnic cleansing}} and {{wp|genocide}}. The replacement of resetteled minorities by Pardarians and Rahelians also draws much continued condemnation. Today, it is a criminal offence in Zorasan to refer to the campaign as a {{wp|crime against humanity}}. | ||

== | == Background == | ||

=== Sattarism and Modernity === | === Sattarism and Modernity === | ||

Revision as of 14:45, 30 March 2023

| Normalisation Modernisation and Harmony Campaign | |

|---|---|

| Part of Zorasani Unification, Rahelian War, Irvadistan War | |

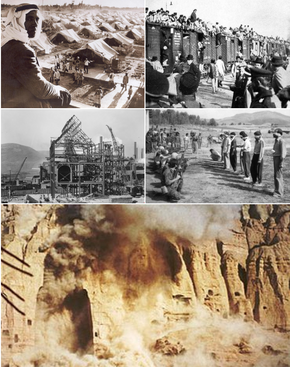

From top-left clockwise: A resettlement camp in Khazestan (1956); Togotis being transported by train to Lake Zindarud; Rahelian tribal leaders before a firing squad (1979); the destruction of the Great Zohist Monument in southern Pardaran (1982); Construction of one of many factories in new industrial cities | |

| Location | Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, Zorasan |

| Date | 1951-1988 |

| Target | Political opponents, Gâvmêšân, ethnic minorities, and occupied territory citizens |

Attack type | population transfer, ethnic cleansing, forced labor, genocide, classicide, |

| Deaths | 980,000-3,980,000 |

| Perpetrators | Zorasani Revolutionary Army, UCF |

| Motive | Modernisation, industrialisation, urbanisation and internal stability |

The Modernisation and Harmony Campaign (Pasdani: کرزیر نوژزه و توفیق; Kârzâr-e Nojāze va Tavāfogh; Rahelian: حملة التحديث والانسجام; Ḥamlat Taḥdīṯ al-Insijām) was a thirty-seven year state campaign conducted between 1951 and 1988 by the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran, and its successor state, the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, aimed at stabilising and modernising the country. It ran from the beginning of Zorasani Unification and eight years after its completion, and involved the forced relocation of ethnic minorities, ethnic cleansing, cultural genocide, rapid industrialisation, urbanisation and classicide. Between 1950 and 1988, an estimated 16.4 million people were relocated from their homes to different regions of the country, of these, roughly 8.2 million were forced to live in new industrial cities and new agricultural lands, while numerous cultural norms and systems were dismantled, including Rahelian tribes, nomadism and the repression of minority religions. By its end, between 980,000-3,980,000 people were killed directly or indirectly during the campaign, urbanisation rose from 15% to 64% by 1988 and Zorasan emerged as one of the most industrialised countries in Coius.

The Modernity and Harmony Campaign was devised by the government of Mahrdad Ali Sattari during the late stages of the Pardarian Civil War as a means of rapidly modernising the nation, to prevent the return of the colonial powers and to provide the state with the economic and industrial base from which it could militarily achieve unification. Sattari and his inner-circle identified a variety of "obstinate elements" of Zorasani society and culture that held the nation back from modernising into an economic and political powerhouse, this included certain ethnic minorities, the Rahelian tribal system, Steppe nomadism, wealthy landowners and their political opponents. The ruling ideology Sattarism, included a focus upon what it termed "modernity" (Ḥadāṯa), this was an all-encompassing term denoting the necessary adoption of technology, science and industry as well as the corresponding social changes needed to achieve "modernity." Sattarism also blamed these "obstinate elements" for the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan and Euclean domination, and would need to be destroyed to avoid a repeat. The targetting of ethnic and religious minorities for relocation was justified under claims that these "strategically placed peoples" would be most resilient to unification and adoption of a unifying Zorasani culture and indentity, therefore their homelands or areas of concentration would need to be broken up. The primary targets for relocation were Togotis, Kexri, Chanwans, Yesienians and adherents of Badi, in most cases hundreds of thousands were displaced and their former homes resettled by either Pardarians or Rahelians as a means of diminishing their concentration within geographical areas. Those displaced were re-setteled thousands of kilometres away, in either pre-built housing districts around new agricultural lands or industrial cities, or in some cases, forced to construct their homes from scratch in isolated areas. From 1958 to 1981, the campaign targetted perceived enemies of both the state and the campaign itself, who the government dubbed Gâvmêšân (Pasdani for Buffalo, in apparent reference to their "stubborness"), this group included tribal leaders, critics of the Sattarist state, socialists, wealthy peasants and shepards, monarchists and those related to the Pardarian, Khazi and the northern Rahelian royal families; the latter targeted mostly during the Rahelian War.

The campaign began to drawdown by 1985 and was officially dissolved in 1988 by order of the Central Command Council, which proclaimed the Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics, "unified, stabilised and introduced to social harmony." While the campaign delivered rapid urbanisation, industrialisation and modern technologies, it also significantly disrupted the lives of millions, who were evicted and transported away from their communities or places of birth. The attacks on cultural uniqueness of the various minorities has led many to accuse the campaign to have engaged in cultural genocide, while the cost in lives from both direct violence and indirectly through resettlement has led others to describe a viable case of ethnic cleansing and genocide. The replacement of resetteled minorities by Pardarians and Rahelians also draws much continued condemnation. Today, it is a criminal offence in Zorasan to refer to the campaign as a crime against humanity.

Background

Sattarism and Modernity

The origins of the campaign lay within the ideological framework of the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command and National Renovationism, also known as Sattarism. The Sattarist embrace of ‘Modernity’, was derived from the adopted the Rahelian language word ḥadāṯa, meaning ‘newness’ or ‘modernism’ and conceptualised the importance of industrialisation, urbanisation, technology, science and mechanised agriculture. The objective of achieving a modern state was derived from the Sattarist ideological reaction to the Etrurian conquest of Zorasan (1819-1860), which was blamed on the Gorsanid Empire’s superstition toward modern technology, failure to industrialise, failure to modernise its armies and the persistent undermining of state cohesion through Sattarists referred to as “Negative Sentimentalities” – nomadism, tribalism, regionalism for example. Mahrdad Ali Sattari, the leading founding father of Zorasan would repeatedly argue that failures to overcome those shortcomings would condemn the country to subservience to Euclea and other major powers alike. Furthermore, leading Sattarists further claimed that the adoption of modern economics and technology would be inescapable if Zorasan was to be reunified either through military force or more peaceful means. This overwhelming focus on the need to modernise society through urbanisations and industrialisation led to the ultimate condemnation of traditional norms among Pardarian and later Zorasani societies, lending to the argument that the Modernisation and Harmony Campaign can also be classified as a cultural revolution.

Mahrdad Ali Sattari, 1947

Zorasan being predominately agrarian in nature throughout Etrurian rule, bar the exceptions of select cities, which the Etrurians developed to process raw materials for export back to metropolitan Etruria, meant that rapid industrialisation would require the relocation of people to cities. This in turn would require a break with the agrarian past in terms of societal functions and traditions, which in turn was welcomed by many senior figures within the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command as integral to the “facilitation of national restoration.” In speech prior to the outbreak of the Pardarian Civil War, Mahrdad Ali Sattari told a rally of supporters, "our path to reunification and national restoration lays upon the railroads, the highways straight to the smoking foundries and steel mills, we will reach this land of industrious productivity mercilessly."

The role of ‘Modernism’ within Sattarist thought also took to demand a transformation of society and the individual citizen. The Modernisation campaign would not only transform the country from an agrarian, superstitious and impoverished society into a heavily industrialised and modern one, but would also through that process, transform every Pardarian – later Zorasani, into a model citizen, imbued with a collective spirit, obedient, subservient to the state’s needs and wholly devoid of any individualistic motivation. Historians and modern day commentators note that the "ideal man" within National Renovationism was one defined via the "Cult of Science" and the "Worker-Soldier." The National Renovationist "Cult of Science" was centred around the admiration of technological progress and the transformative influence it hands on the standing of nations - in essence they held that the more scientifically advanced a nation was, the more powerful it was. This lay in line with the near romanticised view of industry, in that “billowing smokestacks” would be the “banners of progress and national wealth.” The National Renovationists further to the point, viewed industry as the principal provider of the means of defence, without adequate industrial capacities, a nation would forever be weak and vulnerable to the predations of more powerful neighbours or the global powers. This conflation of industry with defence fed into the idealised “Worker-Soldier” or the image of a Zorasani man with one hand wielding a spanner and the other a rifle, in peacetime providing himself and the nation with the means to defend the homeland in wartime.

The more extreme results of the campaign, notably the cases of genocide against the Zorasani-Satrians, the Yeniseians, and massacres of the Sotirians and Badists were in themselves drawn out of entrenched Pardarian Chauvinistic views of these groups as “External” or “Alien” (خارجی; Xâreji) – outsiders brought in by Etrurian imperial authorities and inherently incompatible with the Sattarist-National Renovationist ideal for Zorasan. These groups therefore, posed obstacles to the successful modernisation of society and even posed threats to long-term national and societal security.

In mid to late 1947, the Central Command Council, the top-decision making body of the Pardarian Revolutionary Resistance Command met to formulate plans to intitiate Sattari's desired drive for modernisation and modernity. It was found that despite holding near universal support, divisions arose on how far and expansive the drive should be. Several members led by Ershad Kharimpour were concerned that forcing the peoples of the Great Steppe to adopt sedentary and industrialised living would provoke resistance. This group was counted by hardliners led by Habibollah Mousavi and Erkin Dostum who championed the drive as a means of "eradicating the cultural defecits" found in the Steppe populations, ultimately, Mahrdad Ali Sattari himself would settle this particular division by claiming that only through mass mobilisation of all Pardarian citizens would modernity be achieved. He further argued that nomadic lifestyles and the agrarian-subsistence culture of the Steppe had no place in an industrialised, militarised Pardaran.

These meetings would formalise the general outline of the Modernisation Campaign and was formally adopted by the Revolutionary Command Congress in December 1947, however, the outbreak of the Pardarian Civil War months later in 1948 forced a stall upon the plans, with focus placed upon mobilising fighting age men and eradicating various factions and their supporters within liberated territories. The defeat of the Sublime State of Pardaran - the Shahdom, as well as the various smaller warlord states and Ashkezar Republic was followed swiftly with the establishment of the National Republic of Pardaran. However, plans would be further delayed with the outbreak of the Khazi Revolution in neighbouring Khazestan.

Initial preparations

Planning and objectives

Socio-economic situation

With the annexation of the Free Kexri Republic into the Union of Zorasan, the new government felt confident in its position to begin implementing the “Strategy for Modernisation and Harmony” across all three Union Republics. However, the Union Command Council found the socio-economic situation to be considerably varied between the three Union Republics, these differences lay as legacies of both Etrurian rule and post-independence misrule. The Command Council further found that initial plans were drawn up in great detail for Pardaran and less so for Khazestan, neither delegations held detail understandings or knowledge of Ninevar’s economic and productive infrastructure, let alone the demographic reality.

At the turn of 1953, the Union of Zorasan boasted a total population of 38.56 million with Pardaran having a population of 26.65 million, Khazestan having 6.27 million people and Ninevar populated by 5.64 million. However, of the three Union Republics, only Khazestan had levels of urbanisation approaching the least developed Euclean countries, with the rate of population residing in towns and cities at 33.39% - both Pardaran and Ninevar stood at ~18%. The major cities were limited in number (those with populations above 500,000) to Zahedan, Bandar-e Parvadeh, Faidah, Borazjan and Soltanabad, this was noted by the Command Council and the cities were earmarked for dramatic expansion, as well as the construction of new industrial cities and urban areas to support mining efforts.

In terms of socioeconomic life, all three Union Republics were predominantly agrarian, owing to the decades long policy by Etruria of utilising the fertile soil of Zorasan to mass produce crops for consumption by its metropolitan population. This meant that upon independence, the post-Solarian War states of Zorasan had all but inherited agricultures capable of feeding their populations but also enabling the export of surplus crops. With the exception of select regions of Pardaran and Khazestan, where mining and resource extraction was prominent, the centrality of farming and husbandry to ordinary Zorasanis was such that many localities held strong identities built around the soil and nature, an issue that would cause considerable resistance upon the relocation of rural populations into industrial cities.

Existing industry, including productive manufactory did not exist outside select coastal cities that were developed by Etruria and Estmere and in most cases, these had been limited to refining resources extracted from the Coian interior before being shipped to Etruria and Estmere for processing into consumer goods or for use in industry. What existed was insufficient to provide the Union with the materials and goods necessary to maintain a sustainable level of development, but would provide foundations upon which wider and more expansive industries could be constructed.

The most valuable resource exploited by 1953 was the discovered oil reserves in northern Khazestan and the vast off-shore fields of oil and natural gas along the Pardarian coastline. The first rudimentary off-shore oil rigs were constructed by the Etrurians between 1940 and 1941 and remained intact upon the Coian Evacuation, however, the technology to truly exploit off-shore fields would emerge until the 1960s. The on-shore facilities in Khazestan were to be dramatically expanded during the Modernisation Campaign, aided by investment and expertise provided by Werania. The Command Council’s “Strategy for Modernisation and Harmony” detailed how the export of petrochemicals would secure the necessary capital to sustain the campaign’s need for imported machinery and materials.