User:Tranvea/Sandbox 1: Difference between revisions

| Line 80: | Line 80: | ||

=== Cold War (1953-1965) === | === Cold War (1953-1965) === | ||

=== Rahelian War === | === Rahelian War (1965-1968) === | ||

=== Demise === | === Demise === | ||

== Geography == | == Geography == | ||

Revision as of 01:20, 28 December 2020

Zubaydi Rahelian Federation الاتحاد الراحلي الزبيدي al-Ittihād al-Rāhiliyy al-Zubaydiyy | |||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1953-1968 | |||||||||||

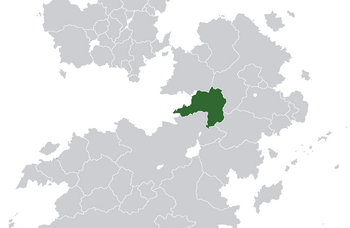

Location of the Zubaydi Rahelian Federation in green. | |||||||||||

| Capital | Sadah | ||||||||||

| Government | Federal absolute monarchy | ||||||||||

| King | |||||||||||

• 1953-1959 | Said Ali I | ||||||||||

• 1959-1968 | Said Ali II | ||||||||||

| Prime Minister | |||||||||||

• 1953-1960 | Hassan Yazeed | ||||||||||

• 1960-1964 | Muqrin bin Abdullah | ||||||||||

• 1964 | Salman bin Hassan | ||||||||||

• 1964-1966 | Abdullah bin Hussein | ||||||||||

• 1964-1968 | Nasir bin Hussein | ||||||||||

| Legislature | None | ||||||||||

| History | |||||||||||

• Established | 16 March 1953 | ||||||||||

| 16 March 1953 | |||||||||||

| 7-11 June 1959 | |||||||||||

| 1965-1968 | |||||||||||

| 9 September 1968 | |||||||||||

| Population | |||||||||||

• | 16,434,000 | ||||||||||

| Currency | Dinar | ||||||||||

| |||||||||||

| Today part of | |||||||||||

The Zubaydi Rahelian Federation (Rahelian: الاتحاد الراحلي الزبيدي; al-Ittihād al-Rāhiliyy al-Zubaydiyy) was a country that existed from 1953 until 1968, that was formed through the union of Riyadha and Irvadistan. Although the name implies a federal structure, it was de facto a confederation, with significant autonomy granted to each state.

The federation was established on 16 March 1953 in response to the formation of the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran during the early stages of Zorasani Unification. The union was agreed by Said Ali I of Irvadistan and Abdullah-Yazid of Riyadha, who had in the past, established close inter-familial ties through marriage. Both monarchs recognised the threat the UKP posed to their kingdoms through its ideology of Pan-Zorasanism and republicanism. The union lasted fifteen years and saw the development of a highly productive, economically dynamic state, though throughout its existence it was locked in a bitter cold war with the UKP, suffering from terrorist actions and repeated bouts of instability caused by the competiting ideologies of monarchism and republicanism. In 1965, the tensions erupted into full-scale war between the two nations, despite repelling a UKP invasion with the backing of Euclean powers, the war turned following its own failed attacks against the UKP. Whilst the war ended in a stalemate, the social and economic costs of the conflict, coupled with the rise of radical leftism resulted in the collapse of the union in 1968, when the Irvadi Section of the Workers' Internationale seized the capital of Sadah. After a brief period of civil strife, the ISWI-led forces defeated the monarchist holdouts in Riyadha and established the United Rahelian People's Republic in the federation's place. Eleven years later, the URPR would in turn be defeated by the UKP and it would be absorbed into the Pan-Zorasanist union, establishing the modern day Union of Zorasani Irfanic Republics and marking the success of Zorasani Unification.

History

Formation

Ties between the Zubayd and Al-Hawashim of Irvadistan and Riyadha respectively were warm as early the 1910s. The closeness was aided by their respective positions within the Etrurian colonial administration, where both shared similar duties and responsibilities under the colony of Rahelia Etruriana. In the 1930s, the two families became intertwined through a series of marriages and a declaration of friendship. During the late Solarian War period, both families reportedly assisted one another in seizing control of territory as the Etrurian colonial order collapsed.

The recognition of the two kingdoms with the Treaty of Morwall in 1946 cemented their borders and both monarchies moved swiftly to legitimise their governments. As early as 1946, both Riyadha and Irvadistan declared a mutual alliance and in 1949, signed a mutual defence agreement. Both states benefited from relatively stability within the borders, succeeding in drawing international aid for reconstruction. Notably, both governments took little to no interest in the Pardarian Civil War nor the chaotic situation in Khazestan. This changed in 1950, with the defeat and execution of the Pardarian Shah and his sons, in what was described as a “horrific case of regicide.” However, neither government genuinely appreciated the threat of the openly republican and pan-Zorasanist regime emerging in Pardaran.By 1950, however, the mutual concern in At-Turbah and Sadah grew to such an extent that several low-ranking princes in both royal families openly talked of a union but including Khazestan. King Said Ali of Irvadistan bemoaned the heavy handedness of Khazestan’s Hassan ibn Rashid, and he wrote a series of letters to his Khazi counterpart urging for restraint to the early protests. In 1952, the emergence of the Khazi Revolutionary Resistance Command during the violent peak of the Khazi Revolution failed to deliver the realisation of the danger growing in the west.

Essa Talib, a Riyadhi civil servant turned historian, who fled the Federation in 1968 wrote, “there was a genuine ignorance to the threat in Pardaran and Khazestan during the latter’s revolution. Neither the King of Riyadha or Irvadistan truly understood the beast that was to wage war on them a decade later.”

The eruption of conflict within the Kexri Republic would prove pivotal in the two kingdoms progressing toward a union. News that both Khazi and Pardarian soldiers were being infiltrated into the war-torn state deeply unsettled the Irvadi monarchy, as it would place the revolutionary Pardarian state directly on its borders. This was only worsened by the overthrow of the Khazi monarchy by the KRRC in November 1952. The decisive intervention of Khazestan and Pardaran in December 1952, brought about the complete collapse of the Kexri Republic and its replacement by the Provisional Revolutionary Government of Ninevah. The reality of the threat finally reached the two kingdoms with the radio broadcasted speech by Mahrdad Ali Sattari on December 28 1952, saying, “our duties now shall take us to the Peninsula and to Sadah, from where the banner of Zorasan and its republican virtues shall flutter in victorious winds.” According to some documents released in 1999, talks between the two countries about a union began within days of the Kexri Republic’s fall, though it was limited to low-level diplomats and was “exploratory in nature.” The groundwork for the union was supposedly established, though it found some resistance with Riyadha, where mid-level royals saw the proposal as opportunism by the Zubaydi family to expand its territory.

The tripartite talks between Pardaran, Khazestan and Ninevah were not officially declared until January 10, the two kingdoms in the north had become aware of the talks as early January 4. The news was met with pandemonium in Sadah according to several sources, with King Said Ali seeking an immediate counter union between Irvadistan and Riyadha. The King, acutely aware of the misgivings of Riyadhi officials, pressured his own ministers to present his proposal for a union, in which government positions would be reserved for Riyadhis exclusively, if he and his successors would be permitted to rule as the head of state.

Said Ali, enjoyed a close friendship with Emir Abdullah-Yazid of Riyadha and the two also held mutual relations through the marriage of their respective children prior to the Solarian War. Within a week of the UKP’s formation, Said Ali exchanged letters with Abdullah-Yazid regarding a possible union between Irvadistan and Riyadha, though falling far short of closing the demographic gap, a union would in Said Ali’s view, “do much to pool our resources against the same radical Pardarian-Rahelian threat of Pan-Zorasanism.” In Said Ali’s view, if one of the monarchies fell, the other would fall in quick succession. The proposal received mixed reviews in Riyadha, with some of the elite families in the peninsula-kingdom fearing this to be a plot by Irvadistan’s King for expand his kingdom.

On February 19, Crown Prince Ali Said ibn Said, who was also married to the eldest daughter of Emir Abdullah-Yazid travelled to At-Turbah to personally lobby the Riyadhi monarch on behalf of his father. According to documents seized in 1979, Ali Said assured Abdullah-Yazid, that he and his family would retain full influence of Riyadhi affairs and that power in a union would be shared equally. Ali Said made much of the historic ties between the Zubayd (Irvadistan’s ruling family) and the Safwadi (Riyadha’s ruling family) as well as their present-day ties through marriage. On February 22, Abdullah-Yazid conceded to bilateral talks for a possible union.

The talks progressed rapidly, with the Irvadis proposing an absolute monarchy. However, to mitigate Riyadhi concerns, they proposed the monarch to be of the Zubaydi tribe, while the Prime Minister and all success heads of government would be Riyadhi, as well as half the cabinet. The Riyadhi would provide the command and personnel for the navy and air force, while the Irvadis would provide the land forces. Both kingdoms would retain a National Guard for exclusive internal use. Unlike the UKP, the proposed union would not integrate the kingdom’s economies to such a degree, though a common currency would be utilised and common customs union, both kingdoms would retain their own oil companies and others, while both states would be permitted to dispatch diplomats to foreign countries.

Cold War (1953-1965)

Rahelian War (1965-1968)

Demise

Geography

Government and politics

Officially, the country was a federal absolute monarchy with significant powers granted to the King both in executive and legislative forms. However, the country was a de-facto confederation, with significant powers and autonomy delegated to the two states comprising the federation. Such was the degree of de-centralisation, the only primary duties of the central government was defence, national security, foreign policy and the management of trade and customs. The two constiuent kingdoms retained control over virtually all other areas of national policy. The Federation itself was mostly defined by its sharing of power between the two royal families and the success it saw in maintaining a relatively stable polity for over fifteen years.

The Basic Law of the Royal Federation adopted upon the signing of the Treaty of At-Turbah, officially desginated the Federation to be an absolute monarchy. The Basic Law stated that the King and all office holders must comply with Esafkar (Irfanic law) and live in accordance to the Es'bat (traditions and virtues of Ashavazdar and the Companions). While no political parties or elections were permitted, each year the Provinces of each Kingdom would hold a MuʾTamar (lit. conference), in which the provincial heads would meet with designated citizens to hear out greivances and suggestions, the results of the Mu'Tamar would be passed onto the central government to acted upon. During its fifteen year existence, three of the fifteen Mu'tamar events included direct-popular votes on initiatives, presenting a limit historic cases of direct democracy. However, the defining feature of the Basic Law was the unique division of power between the royal families of Irvadistan and Riyadha. The two consituent kingdoms were governed internally with marked differences; with Irvadistan dividing itself into provinces, which were in turn governed by individual princes of the Zubayd family. In Riyadha, the Kingdom was subdivided into Emirates, which enjoyed some degree of autonomy and were structured around the historic pre-Etrurian colonial tribal territories. The degree of autonomy in Riyadha led to many claiming itself was federalised within a confederation.

The Basic Law proclaimed the "Kings of Irvadistan to be the Kings of the Federation", while the position of Prime Minister and the Council of Royal Ministers would be held exclusively by members of the Riyadhi royal family. The federal armed forces would be divided by the Army and its officer corps being drawn from Irvadistan, while the Riyadhis would provide the officers for the Navy and Air Force. The Royal Reserve Force would be comprised of officers from both kingdoms and subordinated to the King of the Federation.

The King enjoyed extensive legislative, executive, and judicial functions and royal decrees formed the basis of the country's federal legislation. The Royal Court of the Federation was excluded from the running of the Federation, with the King advised and assisted by the Prime Minister. The Prime Minister presides over the Council of Ministers and the Consultative Conference, which is an annual meeting of prominent figures from both royal families, who discussed important issues and held the Prime Minister to account. As the Prime Minister was drawn from the Riyadhi royal family, the candidate was often proposed by the King of Riyadha and was either a close family member or a trusted court ally - as the Federation headed toward the Rahelian War in 1965, those appointed were often chosen by their qualities and specialities rather than their loyalty to the Riyadhi monarch.

- Kings of the Zubaydi Rahelian Federation

King Said Ali ,

reigned 1953-1959

King Muqrin Ali,

reigned 1959-1968

The Federation in itself was fundamentally weak and highly de-centralised, insofar that the only powers the central government had to itself, were limited to foreign policy, trade, customs, defence and internal security. The two kingdoms were permitted to manage their own affairs, especially in the realms of education, economic development, infrastructure (though this was limited with the introduction of federal roads and railroads in 1955), policing, justice and social matters. The federation adopted a single currency, the Rahelian dinar for use in both states. Both constituent kingdoms were ruled as absolute monarchies, though the Kingdom of Irvadistan was ruled by the Crown Prince of Irvadistan on behalf of the King, who concurrently served as King of the Federation. Any law passed or decreed at the federal level required the ascent of the King of Riyadha and the Crown Prince of Irvadistan, though a formality, it proved highly conducive to the federation's success. Both King Said Ali and Muqrin Ali, who ruled at the federal level, were so concerned with Riyadha refusing ascent to a decree, that in all cases the Riyadhi monarch was consulated at every juncture, leading to many historians arguing that the Federation had a de-facto dual monarchy.

- Prime Ministers of the Zubaydi Rahelian Federation

Hassan Yazeed,

served 1953-1960

Muqrin bin Abdullah,

served 1960-1964

Salman bin Hassan,

served 1964

- King Khalid bin Abdulaziz Official.jpg

Abdullah bin Hussein,

served 1964-1966

- Sabah III as-Salim as-Sabah (cropped).jpg

Nasir bin Hussein,

served 1966-1968

Foreign relations

Throughout its existence, the Federation sought close relations with Euclean great powers, to which they saw as the most viable option for deterring aggression from the Union of Khazestan and Pardaran. Second to its desire for protection was the need to secure foreign investment to assist in economic development and the expansion of its oil and gas reserves. This outreached proved most successful with Estmere, Werania and Halland, with some degree of success seen with Etruria and Gaullica.

The Federation’s outreach to Halland was initially based on the desire for assistance in the modernisation of its armed forces, this in turn led to the Hallandic Mission to the Zubaydi Rahelian Federation (HAMZURFED) in 1955. In Estmere’s case, its links grew from the desire for economic investment to include military assistance. Between 1953 and 1963, Khalifa al-Khandari served as the Federation’s Foreign Minister, he was widely acclaimed in Euclean capitals and proved instrumental in gaining Euclean support against the UKP. However, the Federation’s external relations would suffer after Al-Khandari was assassinated by the Black Hand in 1963.

The Federation’s attempts at a regional bloc to counter the UKP proved less successful. Its early successes with Tsabara were notable, however short-lived, with the overthrow of the government by the left-wing Communalist movement. The UKP’s support for anti-colonial movements in Bahia during the 1950s, granted it allies and supports in the sub-continent, further isolating the Federation within Coius.

The Federation’s relationship with the UKP was complex and intrinsically antagonistic. Neither government operated embassies in their respective capitals, owing to the UKP’s refusal to recognise the Federation as a sovereign state. Cross-border trade was near non-existent and the only forms of cross-border travel that were recorded were isolated to a minority of nomadic Rahelian communities. An attempt was made to normalise ties in 1959, but this failed to materialise any normalisation with the onset of the Black Hand’s attacks on Federation soil.

Military

The Royal Armed Forces of the Zubaydi Rahelian Federation, though commonly known as the Royal Armed Forces were divided into four branches: the Royal Zubaydi Federal Army (RZFA), Royal Zubaydi Federal Air Force (RZFAF), Royal Zubaydi Federal Navy (RZFN) and the Royal Reserve Force (RRF). The Royal Armed Forces were managed by the Ministry of Defence, with the King of the Federation serving as commander-in-chief. Per the Basic Law of 1953, the armed forces were divided between the two states in terms of contribution of officers – Riyadha provided the officer corps for the Air Force and Navy, while Irvadistan provided for the Army. The Royal Reserve Force was split equally between the two states. Operating within each Kingdom were the Royal Territorial Forces, which were commanded by the constituent capitals rather than the federal government.

Owing to the threat of the UKP, the Royal Armed Forces were relatively large in relation to the country’s population, with over 450,000 active and reserve personnel serving throughout most of its history. The Estmerish and Hallandic missions to the Federation beginning in the 1950s, proved decisive in the quality of training and armament of Zubaydi troops. The Zubaydi approach to the foreign missions was based on the slogan, “imitation in culture, training and emotion of battle.” By the outbreak of the Rahelian War in 1965, one Estmerish officer remarked, “if we had ever wished to see the birth of the Estmerish condition in foreigners, our Zubaydi allies is that truly.” One of Estmere's contributions was the creation of the much vaunted Royal Sand Raiders (غزاة رَمْل مَلَكِيّ; Ghazah al-Raml al-Malakiyy), an elite highly mobile special forces unit. The Royal Army also boasted a large number of armoured vehicles and tanks, and was noted for its motivation, discipline and training. In 1960, the Royal Zubaydi Federal Air Force began to receive modern jet aircraft from Estmere, with two-full squadrons of Hawker Hunters being delivered by 1963. By the onset of the Rahelian War, the Zubaydi Air Force boasted over 50 jet aircraft, though it would suffer catestrophic losses between 1965 and 1966 owing to the UKP's air force's larger numbers, though the ratio of losses would rest in the Zubaydi's favour.