Ratukunti

In Hindia Belandan myth, the Ratukunti is a demon whose origins lie in prehistoric Hindia Belandan cultures. The Ratukunti is said to be the leader of the boentianaks, who are vengeful vampiric beings transformed from the spirits of women who died during childbirth. Whilst the boentianaks were human, the Ratukunti is not but only takes on a human form when making an apparition in order to lure unsuspecting people who may be wandering alone on certain nights of the year. When taking a human form, the Ratukunti is described as a lady with facial tattoos, suggesting Austronesian origins, wearing a long robe often associated with the Andjanian nobility and an elaborate headgear with palm fronds. The prevalence of the Ratukunti in virtually every folklore of all islands in Hindia Belanda except the island of Papoea suggests that it was spread by Andjanians during the expansionist period of the Andjani Empire.[1]

Origins

Hindia Belandan folklore features a strong undercurrent of animistic beliefs revolving around nature worship, including the belief that the environment in which humans live are concurrently populated with different kinds of spirits. These beliefs have their origins in the prehistoric and early historical Hindia Belanda, when Austronesian societies began to emerge across the archipelago along with a nascent belief system surrounding the power of nature as manifested in these spirits. Austronesians believed that the actions of these spirits are connected with natural phenomena and commensurate with human actions toward nature itself, thus a spirit is neither inherently malevolent or benevolent. A spirit, if not cared for by performing the appropriate rituals which usually entail caring for the natural environment with which the spirit is associated, may inflict harm on people and society. But if a spirit is appeased, it will in turn give rewards in various forms. It was only in the early 11th-century that these spirits began to be associated with inherent goodness and evil. The Ratukunti, once a spirit believed by the early Austronesians to be responsible for the falling of the night, became associated with evil during the expansionist period of the Andjani Empire, when most of the islands in the archipelago fell under Andjanian rule.

It has been hypothesised[2] that the sudden change in the Ratukunti's role was intentional in order to transform the myth into a social engineering tool to discourage people from travelling alone at night and thus becoming targets of criminals and wild animals alike. In losing its role as a neutral spirit of the night, the Ratukunti effectively became a policing force that deterred criminals and prevented the masses from falling victims to the former.[3] There is a growing body of evidence to suggest that the myth of the Ratukunti was also used by the Andjani Empire to reduce the risk of fire, as one variation of the myth tells that the Ratukunti will visit a house at night unless all fire and lighting within it are covered by nightfall or before the occupants go to sleep.[4]

Throughout Hindia Belandan history, the Ratukunti has been linked to the sudden disappearance of people.

Appearance and characteristics

The colonial-era anthropologist Emma K. de Vries wrote about the Ratukunti as described to her by a village chief in her 1913 seminal work Boekoe Hikajat Hantoe Hindia-Belanda, detailing Hindia Belandan supernatural entities.

During the five days that I remained in the village of Poe'oen Terbang, in the Regentschap Kelawi on the island of Somatra, I happened upon the village chief, named Abdorahman, whom I enquired regarding the nature of the Ratukunti. Hesitant at first – and understandably so as even the utterance of her name is said to bring a series of misfortunes – the village chief agreed to describe the Ratukunti to me as we sat on his veranda. A Sunni Mohammedan, as are most inhabitants of this village, Abdorahman began by reciting a prayer in Riysan to ward off evil. He then gargled with some water infused with pandan and spat onto the ground in front of us. This markedly Animist ritual, I later learnt, is one of several ways one can protect oneself from the Ratukunti.

Abdorahman then told me that the Ratukunti is not human, but rather a demon whose origins is not of this earth. A cunning and evil being, the Ratukunti is able to transform into human form on certain nights of the year, donning the robe of ancient Andjanian nobility and a palm fronds headgear, to lure an unsuspecting person who may be wandering alone at night. Once she finds a victim, she uses her sharp, long nails to stab their heart and thereupon her gruesome feast may begin. If she is interrupted during her feast by multiple people, the Ratukunti will fly away, leaving the body of her victim. But if interrupted by another unsuspecting and solitary person, she will do unto that person that which she has done to her other victim. Abdorahman then told me that it is not safe to talk about the Ratukunti on certain nights of the year in the Javanese calendar: the first night of the second month; the second night of the eighth month; and the twentieth night of the tenth month, the last of which is known as the 'Night of the Great Kunti', the most supernaturally dangerous of all nights. [5]

Apparition

An apparition of the Ratukunti is said to be preceded by a sudden drop in temperature and a loud cackling. When the Ratukunti is far, the cackling can be heard loudly, but when she is near the cackling grows faint.[6] When she is about to attack, the cackling ceases entirely and a swooshing sound of her robe can be heard. According to Emma K. de Vries, when the cackling of the Ratukunti begins to grow faint, signalling her approach, a person may chant the following incantation to thwart her attack:

Wahai Ratukunti terkoetoek (O you accursed Ratukunti),

Matilah kaoe di timpa tanah pertimboenan (May you be struck dead by the soil from the grave-mound).

Maka kami potong engsel bambu, jang pandjang dan jang pendek (Thus we cut the bamboo-joints, the long and the short),

Agar didalamnja kami masak kaoe poenja hati haloes (To cook therein this spectral liver of yours).

Aku tahoe kaoe poenja asal (I know your provenance),

Dari tempat kotor kaoe mandjadi (from a filthy place you have come,)

Kalaoe ta' oendoer dari sini (if you refuse to retreat from here),

Di timpa ampat pendjaga pendjoeroe (you will be struck dead by the guardians of the four cardinal directions),

Wahai balang kotor Ratukunti (O you unclean spirit Ratukunti),

Kaoe penghoeni kotor doenia beranta (You filthy inhabitant of the netherworld),

Hilanglah dan terkoetoeklah! (Begone and be damned!)

Naik saksi kekoewatan Toehankoe: (Witness the power of our Lord)

(A prayer according to the religious beliefs of the person chanting this incantation is said at this part)

Talismans

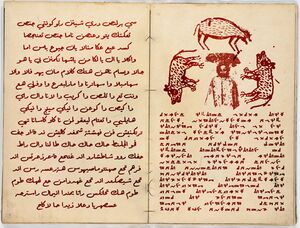

Talismanic manuscripts were also commonly employed to scare the Ratukunti away. Many talismanic designs, often incorporating Islamic and Christian prayers alongside an animist one, were created and used widely across the archipelago, despite being frowned upon by Esoteric Shia and Church of Hindia Belanda clergies. The strong undercurrent of Animism in the predominantly Shia and Christian Hindia Belandan society of the colonial era created a syncretic belief system that was adopted chiefly by rural communities as a compromise between official religiosity, as manifested in the institutions of the Church of Hindia Belanda and the Auxiliary Imamate, and the Austronesian Animism of the past. These talismans were normally written on a piece of paper and can be carried by a person to protect them in their travels, buried under crossroads or near the entry of a building to deter the Ratukunti. Most of these manuscripts include a visual depiction of the Ratukunti to help the owner identify the Ratukunti from afar should they be unfortunate enough to cross paths with her.

The drawing of the Ratukunti's likeness on these talismanic manuscripts also plays a role in protecting the owner from falling victim to her. Incantations, prayers and symbols are often written around the drawing, which act as a bind that restricts the Ratukunti's movement when she is nearby. Symbols such as the Seal of Solomon, considered by Esoteric Shias as a strong shield against general malevolence, and Saint Benedict Medal, are often drawn on these manuscripts to render the Ratukunti powerless. Images of beasts encircling the Ratukunti were sometimes featured in some talismanic designs to achieve the same effect. Although this syncretic practice was officially disapproved of, Hindia Belandan communities continued to observe it until at least the 1920s, when belief in Hindia Belandan superstitions experienced a rapid decline due to a wave of rationalism spread by the writings of Hindia Belandan intellectuals.

Most of these talismanic manuscripts were created using red ink made of red iron oxide, although black and even blue ink was sometimes used. Each of these colours was attributed with certain powers against supernatural entities. Red pigment was considered the most potent against powerful beings such as the Ratukunti, hence its predominant use, whilst black pigment made of lampblack is considered most powerful against celestial beings. Blue pigment was used predominantly against water-dwelling beings. Some manuscripts were illuminated which suggest that they were commissioned by the nobility, although it remains unclear if the use of gold is associated with a certain magical property.

Almost all of the talismanic manuscripts against the Ratukunti found to date are nearly idiosyncratic; no two manuscripts are the same, except for the drawing of the Ratukunti's likeness as its uniformity is crucial for identifying the mythical being out in the open.

Night of the Great Kunti

Pre-1920s observance

According to Emma K. de Vries, the Ratukunti is guaranteed to make an apparition on the Night of the Great Kunti, which falls on the twentieth night of the tenth month in the Andjanian calendar. On this night, inhabitants of each town often congregate together at the town balé, seeking safety in numbers, where they keep vigil from nightfall until dawn. Only at first light may the inhabitants safely return to their homes.

The day before the Night of the Great Kunti, a committee is normally set up in a given town to prepare for the meal that will be consumed by the townsfolk at the balé as they keep the vigil. Several houses are designated as kitchens, each tasked with preparing certain food and beverages for the occasion. Before sunset on the Night of the Great Kunti, town criers wearing black attire tour the town going door to door alerting the townsfolk of the dangers of being home on that particular night. The townsfolk are then escorted to the town balé by nightwatchmen. During the all-night vigil, prayers are said ceaselessly and braziers surrounding the balé are kept lit until the next morning, whilst essential oil made of Jasmine is burnt to summon benevolent protector spirits. Nobody is to leave the balé and the surrounding area during the vigil. Nightwatchmen, made up of men and women alike wearing traditional dress and carrying amulets and talismanic manuscripts patrol the town to look for signs of the Ratukunti's apparition. Each contingent of nightwatchmen consists of at least seven people and those patrolling the town are forbidden to wear any footwear as the efficacy of the amulets used on this particular night is said to depend on continual and direct contact of the body with the earth.

Modern day observance

Nowadays, the Night of the Great Kunti is considered a festive occasion, as belief in the Ratukunti is almost extinct in modern Hindia Belandan society. Whilst some traditions of the past are kept on this night, they have lost their superstitious meanings and are celebrated only for their cultural significance. The gathering at the balé and the all-night vigil are still observed, however the majority of the observances on this night centre around the promotion of the arts and idea of national unity. Hindia Belandans take to the streets, carrying torches and wearing white robes, in major cities to celebrate the Ratukunti as a cultural icon. On this night, museums, art galleries and cultural institutions open their doors free of charge, whilst restaurants and cafés stay open until the next morning. As celebrations of the Night of the Great Kunti tend to get rowdy, some areas where there are hospitals and medical institutions are made off-limits to revellers.

By tradition, the Governor-General of Hindia Belanda holds a gala dinner dedicated to humanitarian causes at Buitenzorg Palace on the Night of the Great Kunti.

Regional variations

Notable apparitions

Pulu Teh, 1912

North Batavia, 1918

Jakarta, 1933

As a cultural icon

Notes

References

- Ladjoeng, Hartono (2007). "Some reflections on the sociological functions of Hindia Belandan folk beliefs", The Hindia Belandan Journal of Anthropology: 340. 3 September 2007

- Rahajoe, Agustina (2003). "Scaring into compliance: the role of 'Cerita Hantu' in early Hindia Belandan society", Anthropologica Hindia Belanda: 280. 12 April 2003

- de Vries, Emma Karolina (1913). Boekoe Hikajat Hantoe Hindia-Belanda, Batavia: Uitgeverij Koenraad